This article was originally written in 2004 and slightly edited now, primarily to prove that I’ve heard of AI.

In Philip Dick’s 1981 science fiction novel The Divine Invasion, the protagonist works for a space industrialist and is stationed, alone, on a remote, unlivable planet. To cope with the isolation, he plays over and over a worn collection of tapes of the music of an intergalactically famous female singer. Her haunting, seductive voice and complex lyrics keep him sane. He is obsessed with her – no, more than that, he’s addicted to her, panicking hysterically at one point when he thinks he has lost the tapes.

When he has finished his essentially menial work, he darkens his hermetically sealed pod, lies back, plays one of the tapes, closes his eyes and is transported to her magical universe as her ethereal presence fills the room. Not just her music but her existence is his refuge, her complicated, celebrated and fabulously successful life the mist into which he dissolves his grimness and tedium.

What he doesn’t know is that she doesn’t exist. In the ultimate in-studio production — and in perfect synch with us now waking up in a new AI world — not only her sound but her whole being has been manufactured. Her history, career, beauty and every minute experience that in aggregate form a life are synthetic. She has been created to profitably and efficiently satisfy a vast and ingrained consumer need, and she does so perfectly.

Also Read

QUOTE/UNQUOTE

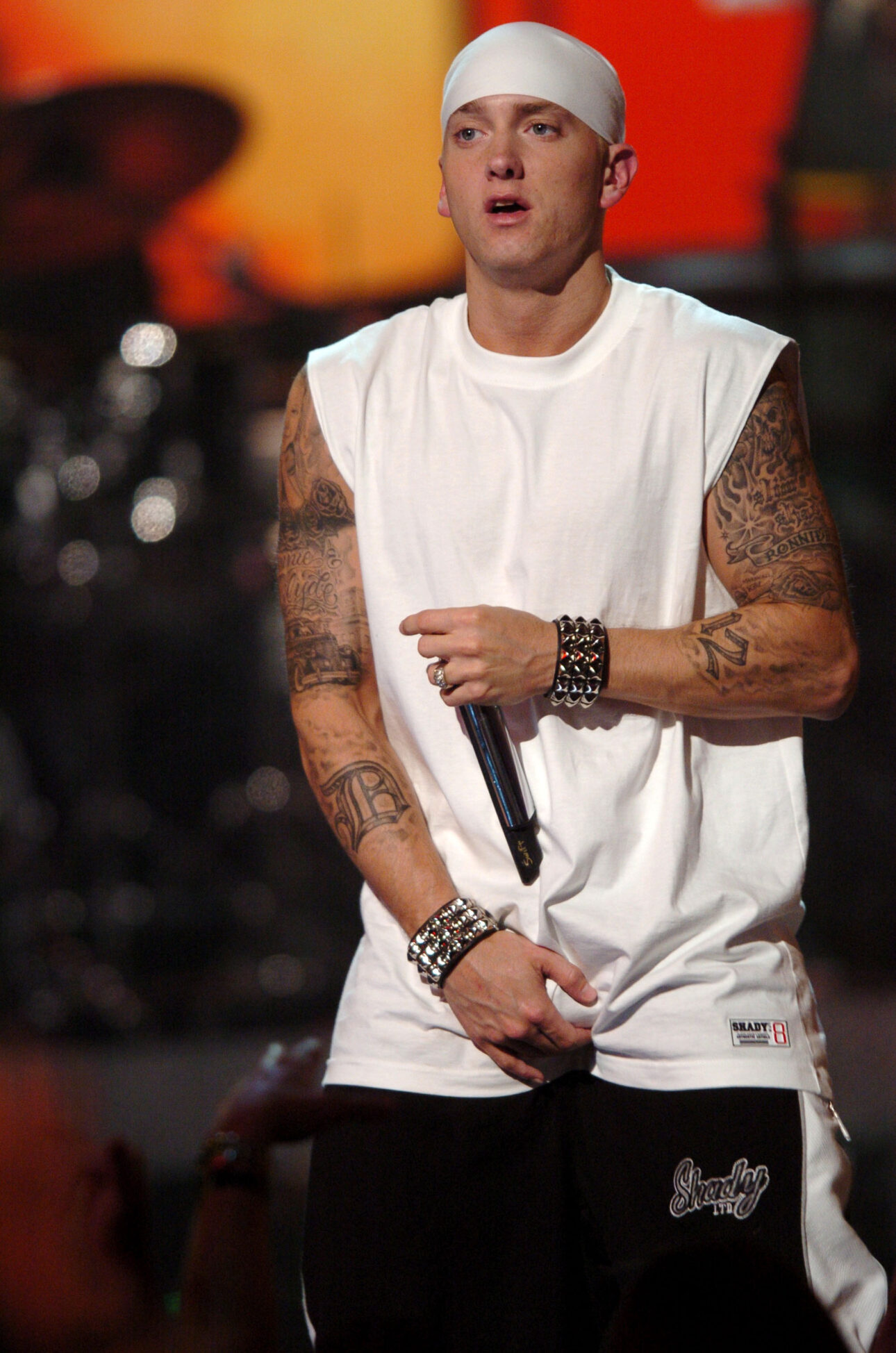

I have always thought Eminem is a little like this. I know he exists but, as the saying goes, if he didn’t, we’d have to invent him. And to a degree, we have. The person may be real but the figure that is Eminem, who is part outlaw, part record industry savior, is a mountain-high papier-mâché god tens of millions of hands have helped build. And what young person, especially a teenager, hasn’t at one time felt like they were marooned on another planet, alone in a loveless void, clinging to the gossamers of sanity expressed in a bodiless voice that miraculously understands, consoles, and soothes?

All successful pop music is the product of the few people who make it and the millions who pull it to themselves and shape it to their own particular desires. And collectively we needed Eminem to shatter our musical lethargy and to stir the stagnant pond of contemporary pop culture, so much of which is blandly mass-produced to be compatible with corporate sponsorship. But the Redeemer came cloaked in the aura of a devil, with the seductive charisma of an antichrist.

Except for a very few people who know him personally, the rest of us only know him as a projection, as we imagine him from what we hear in his lurid and violent songs or as we see him in his various identities in his videos. We watch him at the MTV awards, slumped in his seat, oddly subdued in a t-shirt and glasses, looking both bored and nervously alert, or spurting and convulsing on stage, stabbing at ghosts and screaming profanities at them. We have a collage image of him from photography: his round face that looks like a nun’s when he wears a bandana on his forehead and his sweatshirt-hood up; his fit, tattooed body that makes him look menacing and vulnerable, precocious and already weary. We feel we know him from all this and his incredibly frank music in which his private life is laid out like souvenirs in a tourist shop. Despite being the biggest pop star in the world, or perhaps precisely because of it, he feels to us like he’s our neighbor.

By all laws of statistical probability, we should never have heard of Marshall Bruce Mathers III. His parents were musicians, loosely and briefly, blessed with just enough talent to perform other people’s songs in hotel lobbies across the American Midwest. Their band was ironically named Daddy Warbucks, after the character in the musical Annie, who adopts and looks after the titular orphan, a stroke of beneficence Marshall must have wished for his entire childhood. They married when Debbie was 15 and her husband, whose name is generally not known or at least not spoken, was 22. Within two years Marshall was born and soon after the couple split up. Marshall’s father, who he never knew, moved to California. As a teenager, Marshall tried to contact him, but his letters were returned unread. When Marshall metamorphosed from his white-trash chrysalis into multimillionaire, platinum-selling rap star Eminem, his father apparently tried to reconnect, which Eminem rebuffed saying, understandably: “Fuck that motherfucker, man. Fuck him.”

Teenage, single mother Debbie and little Marshall knocked about between Kansas, Missouri (where he’d been born) and Detroit, where they settled on the impoverished East Side. Marshall was eleven and he and his mother were one of three white families in an otherwise totally black neighborhood, all of which later served as the spiritual and actual background of the movie 8 Mile.

Race was not a big issue when he was younger, Eminem has said, but as he became an adolescent and in his late teens competed in freestyle rap competitions, where he was booed at the mic as invariably the only white contestant, it enveloped him and he saw that his black friends took a lot of heat for backing him up. (This loyalty he has constantly repaid, by the way, most significantly in his patronage of his crew, D12, the Dirty Dozen.)

His life was hard growing up, made more so by his volatile mother, who, he has famously said, was an alcohol and drug abuser who didn’t work but filed frivolous lawsuits in order to get paid off in settlement of them. She also threw him out more regularly than, let’s say, mothers usually reject their children. He failed ninth grade three times and dropped out. He was seventeen, the age other kids were graduating.

He worked menial jobs that paid minimum wage and his existence was about as dead end as the definition gets. All the while he persisted with his dream of making it as a rapper, his one burning, improbable passion. He finally moved out of his mother’s house and in with his high school girlfriend Kim, who he eventually married (and subsequently divorced) and with whom he has a daughter, Hailie. In 1996 he released an independent CD called Infinite. It was his shot at the brass ring, but it was a mediocre record and bombed quickly. He was twenty-four.

Before listening to his most recent singles, the last time I heard Eminem his disembodied voice was coming from the wall of the Superal supermarket outside of Chiusi in Italy. It was the song “Lose Yourself” from 8 Mile, his gunfire raps spraying the parking lot. In the dozens of times I’ve shopped there I’ve always noticed the canned music but never its origin. But Eminem grabs you. There’s an abrasiveness and urgency in his voice that’s disturbing and pleasurable, like scratching yourself. He swirls language around in his mouth and spits it out in elegant streams, like a demented wine taster who can’t stop himself.

It’s trite to say that an artist exploded but in Eminem’s case it’s eerily appropriate, not just to describe his transformation from broke, dissed, white rap-wannabe to the biggest musical star on Earth but also the jarring way he tore like shrapnel into the soft flesh of America’s smug self-image. In 1997, after finishing second at the Rap Olympics in Los Angeles, his demo tape, The Slim Shady EP, found its way to Dr. Dre, the then Don of rap producers, who signed him. He worked on several Dre projects before a year later releasing his major label debut, the Dre-produced The Slim Shady LP. It became the biggest-selling rap record ever at the time, selling over four and a half-million copies.

Even by rap’s jaded standards, Eminem’s tracks were misogynist, violent and homophobic. Surprisingly, they weren’t racist too, perhaps because he may see himself as a black man who has no problems with white people. But he filled that blank space with what must be a hip hop fantasy first: on “Kill You” he cheerfully sings about raping his mother.

As if the invention of Eminem hadn’t been enough to exorcise the wretched reality of his life, Marshall Mathers’ alter ego had created an alter ego, Slim Shady, his true dark side. Eminem thought of him, fittingly enough, on the toilet, and argued it was Shady, his fictional doppelganger, who hated gays, wanted to drug and rape an underage girl and urged a cuckholded husband to kill his unfaithful wife and her lover, whilst verbally bitch-slapping Dre for being hesitant about it.

The record incensed ultra conservatives and ultra liberals, who for once at least had something in common. Gay activist groups and church groups called for his music to be pulled from stores and banned from airplay, and for him not to be allowed to perform at the Grammys or the MTV Awards. The result of this furor was predictable: more sales of the CD and exponential expansion of his fame. His follow-up release The Marshall Mathers CD sold 18 million copies worldwide and was nominated for the Record of the Year Grammy. It didn’t win – the slightly less controversial Steely Dan did – but Eminem won Best Solo Rap Performance and Best Rap Album and, in an attempt to defuse his homophobic stigma, he performed his hit “Stan” with Elton John at the awards ceremony. It was a powerful enough symbolic act to break the political correctness fever. In 2003 he won an Oscar for “Best Original Song” for 8 Mile’s “Lose Yourself,” a movie in which – all protestations aside – he played himself, in his life story, under yet another assumed identity, Jimmy “Rabbit” Smith, Jr. The movie grossed over $100M in the U.S., a staggering success for a music movie starring a first time actor.

The Eminem Show, released in 2002, further fueled the fires of outrage impotently burning at the foot of the monolith Eminem had become. The album covered his incredibly turbulent year in which he was twice arrested on gun and assault charges (he was given suspended sentences), sued by his mother (the case was settled for $1,600), and divorced his wife. It’s a brilliant disc and the aural record of his car crash of a life at the time. On one track, he murders his wife and has his daughter help him dispose of the body. His real daughter Haille sings her part on the track. In an impromptu take-your-daughter-to-work day, Eminem snuck her into the studio, telling her mother he was taking her to Chuck E. Cheese.

Normally, rap stars have magnesium flare-like careers, suddenly, brilliantly lit, relatively quickly over. I think this is because a) there are few love songs and b) most rap is in some way or other the music of revolutions, and revolutions are either won or lost, they don’t go on forever. Rappers flame out as if gunned down in one of their own cop-killer fantasies. Sadly, they then become fashion designers.

Eminem is a mischievous, whirling dervish, wrestling real and imagined demons side by side. We can’t witness the struggle but we see the effects, like watching someone having a nightmare. He has already acknowledged that he can’t rap forever and has said he eventually wants to be an impresario like Dre. He has hinted that he’d be open to acting again. He has given no indication that he has any interest in starting a clothing line.

He also seems, in some way, to be just getting going. At least, he’s showing no signs of mellowing: As he releases his fourth album Encore, he’s already embroiled in a catfight with Michael Jackson, having depicted him as a spastic pedophile in the album’s first single and video “Just Lose It,” and a political battle with President Bush, unflatteringly portrayed in another video the Republicans don’t want aired. Or maybe he’s just stuck in his nightmare, still twisting in his sleep, locked in an impossible battle for his soul with the dark forces that drive him, while we watch, riveted.