Set the scene: 1520 Sedgwick Avenue in the Bronx, August 11, 1973, a summer party in an apartment building’s rec room. Twenty-five cents admission for girls, 50 cents for boys. Olde English 800 or Colt 45 for a buck. Could be just another sweaty night in the city, except that the DJ is up to something different. Instead of playing the hits of the moment, he plays some slow jams — yes — and lots of hard, drum-heavy funk: James Brown’s “Give it Up or Turnit a Loose,” Baby Huey’s “Listen to Me,” the Jimmy Castor Bunch’s “It’s Just Begun.”

He’s a Jamaican-born 18-year-old named Clive Campbell, or DJ Kool Herc, and he’s noticed that some kids only dance to the parts of the songs when everything drops out except the drums, and then they break wild. So that’s what he gives them: playing the break on one of his Garrard turntables, then repeating it on the other, back and forth, back and forth. On the microphone, he and his friend Coke La Rock call out the names of people in the room, giving them status.

Also Read

QUOTE/UNQUOTE

That night 50 years ago, hip-hop came into being.

Everybody knows that story, or at least parts of it. It is hip-hop legend and creation myth, mostly true. The first wave of hip hop stars — Grandmaster Flash, Afrika Bambaataa, MC Sha-Rock, the whole nine — took their cues from Herc and his crew: Coke La Rock, Timmy Tim, Clark Kent, and the rest. How burnished is the legend? Last year a collection of Herc’s gear and memorabilia sold at Christie’s auction house for more than $850,000. An index card bearing an invitation to a party at 1520 Sedgwick fetched $27,720.

What’s less well-known, or less celebrated, is the contribution of the other central figure in that scene: Cindy Campbell, Herc’s younger sister. The party on that August night was hers, to raise money to buy some back-to-school clothes, and she was her brother’s true ride-or-die through all his moves. Many of the records he played — soaking off the labels to conceal them from other DJ’s — were her discoveries. And when rap recordings came, and the next generation moved on without Herc, she helped him manage that transition too. The cultural big bang that is hip-hop would not have been the same without her.

For Herc, as for many of the first generation, the limelight did not last. After being stabbed at one of his parties in 1977, he largely withdrew from the scene, and when his father died in 1984, he fell into a depression and substance abuse disorder, for which he underwent rehab at Daytop Village. By 2011, as the music he created blanketed the world, the founding father had no insurance and had to raise money online for surgery for kidney stones. This year, finally, he will be inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame — the equivalent of Chuck Berry or Little Richard having to wait a half-century for recognition.

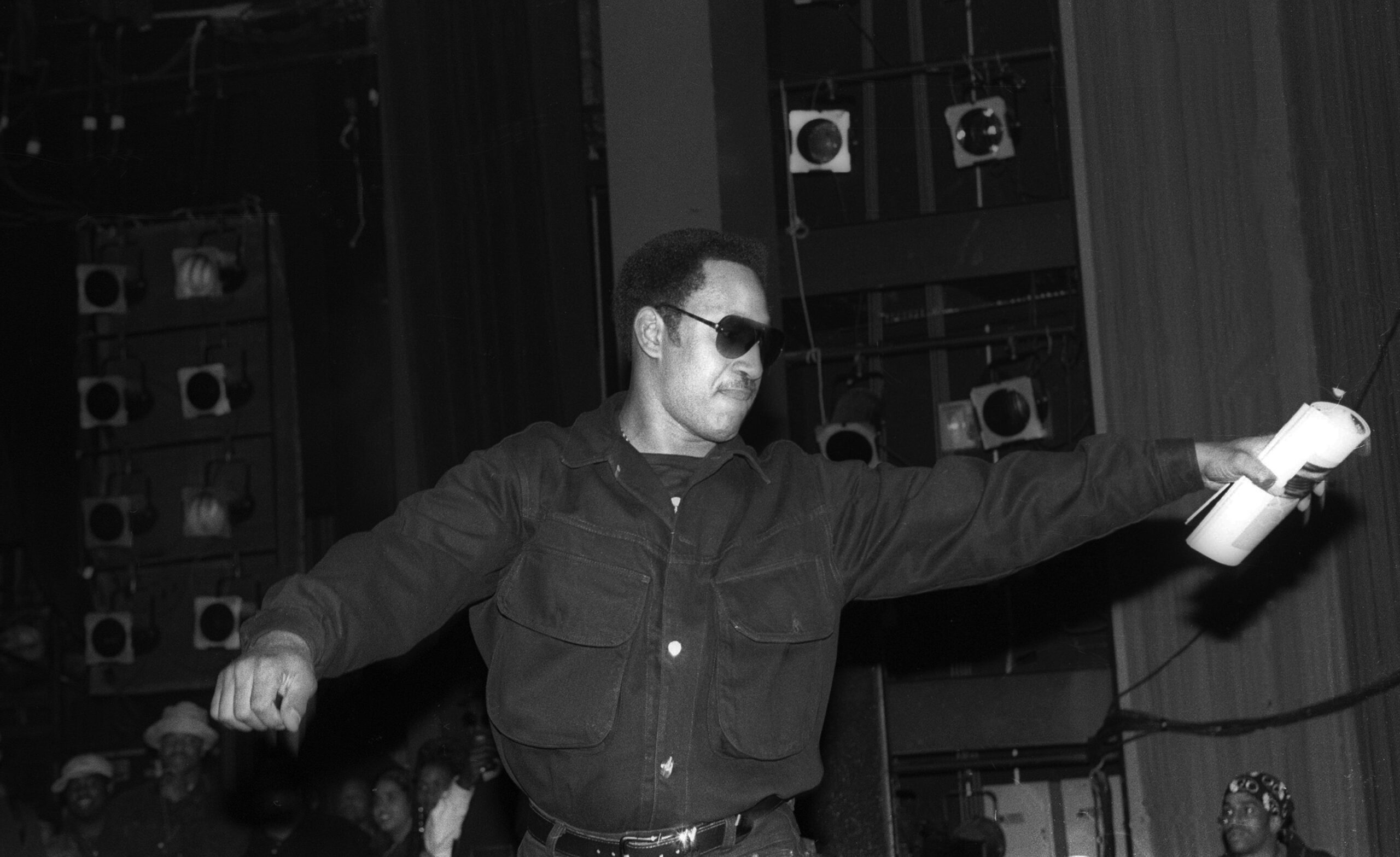

I caught up with Herc and Cindy Campbell at the Cinema Arts Centre in Huntington, Long Island, where she is the multi-cultural arts coordinator. At 68, Herc walks with a cane and has some lacunae in his memory. “I can’t go back that far,” he said. “I don’t fight it. Old age is catching up with me.” He carried a shopping bag full of sunglasses, some in disrepair, from which he tried on half a dozen before settling on one for the interview.

“Glory days,” he said, beaming. “Glory days.”

SPIN: Everybody thinks they know where hip-hop came from, how it began. What don’t they know?

DJ KOOL HERC: Some of them wasn’t born. They go by what their mother told them, or their grandfather told them. I’m the beginning. I’m still young, but still old. The worms didn’t get me. It’s all good.

I can think of one thing people don’t know. People think hip-hop started in the South Bronx, but really it started with you in the West Bronx.

HERC: I went to the west because the South Bronx was burning. Everything was burning. But “South South Bronx” [the iconic chant from Boogie Down Productions’ 1987 song “South Bronx”] sounds strong. “West West Bronx”? Nah.

Cindy, You’re the missing piece of the history.

CINDY: People know it, but they don’t want to write about it or acknowledge it. That’s why there’s some questions that you ask him that he can’t answer. I was there with him, and I know the playlist because I was the one monitoring it and directing it to see where we was going to go. We worked together.

It really began as a family affair.

CINDY: My father was a very musically inclined person. So we always had records playing: Ella Fitzgerald, Nat King Cole, Perry Como, the Big Bopper, any kind of music. My father bought him turntables, and he had everything hooked up in his room. That’s how he learned his skills, how to play the records at home in his room. When I organized the party, he had all that equipment there. So I’m like, I don’t have to pay anybody for music. We have the music already. I told him, this is how it’s going to be. And he moved down from his room to downstairs in the recreation room.

Can we talk about Jamaica? What part of this music comes from Jamaica?

HERC: I would say my start came from Jamaica, and my father was a mechanic at Kingston Wharf. I’ll never forget “White Christmas.” I played that. All that stuff. His favorite person was Ella Fitzgerald. So I know my records. But in Jamaica there were other groups called Byron Lee and the Dragonaires. Then come the Skatalites, and then the Paragons and U-Roy and Big Youth. I learned from that.

Was there something about that music you heard in Jamaica and the way that you heard it that you brought with you, and went into your style of DJing?

HERC: Yeah. Because I knew my records. Even [country star] Jimmy Reeves. I knew that. There’s no racism in my music. Martin Luther King was coming with “I have a dream.” Yeah, yeah. And then he said, if a little white boy and a brother dance together — good. Then I heard Baby Huey say, There’s three kinds of people. There’s white people and there’s Black people and there’s my people. That’s good.

When you moved to the Bronx, what was going on?

HERC: I was learning. My mother said, Don’t let nobody stick needles in my arms. And sniffing glue and all that stuff. I was learning. The first time I saw snow I was like Dennis the Menace.

Someone called me Hercules. I didn’t want to be Hercules. Everybody going to challenge you. I said, Just call me Herc. I dropped the name Clive.

I did graffiti, I took the name Clyde As Kool. Taki 183 was the king. I was following him. I did markers, a little spray. But it smelled, and my father would bust my ass. We called ourselves Ex-Vandals. I would tag “Clyde As Kool.” Those were the days.

When did you start looking for break records?

HERC: I’m always looking for breaks.

But guys before you were playing whole records, and you got the idea to just play the breaks. Where did that come from?

HERC: I was watching a crowd, and everybody was waiting for the breaks to come in. I said, I’m going to do something tonight. I’m going to call it the Merry-Go-Round. I’ll put on two copies of a record, James Brown, “Give it Up or Turnit a Loose,” and just play the break.

How did you find it? ’Cause you didn’t have headphones to listen for it.

HERC: You could see it. If there’s a dark spot, that’s the break. You don’t have to listen. I’m like a shepherd looking over the flock. I watch and watch, and then I noticed that people were waiting for certain parts to come in. Okay. So what happens if I put together all the breaks I got — I wonder how it will do. So I put it on.

How many times would you play a break?

HERC: I wouldn’t go too far. Two times. I’ll just extend it two times. And James Brown says “Clyde” [for drummer Clyde Stubblefield] — that’s my name. So James Brown shouted me out. Oooh. Then the break comes in. I used that to start me off, and then go into the Isley Brothers and [Babe Ruth’s] “The Mexican.” Oooh, I like this. And then Jimmy Castor Bunch. Them were the records, man. I lay claim to it: That’s a Herc record. I’d say, “You never heard it like this before, and you’re back for more.” That’s it.

I wasn’t doing no scratching shit. No. That’s tricks. Tricks are for kids. I played music. It was grown folks’ groove. They can’t dance to no scratching.

CINDY: It’s amazing how certain songs, you know it’s a Herc song, ’cause he found those songs and introduced them to the world. And it gave life to these artists — and residuals, too. So many of them have been sampled so many times.

HERC: And my sister, she knows her music. “Trans-Europe Express” [by Kraftwerk]? I got that from her. She put me onto that. And Queen’s “We Will Rock You.” That was her. Her name was PEP 1.

CINDY: When hip-hop was evolving, we didn’t know what it was. You became a graffiti artist. You started tagging your name. If you were brave enough to go out there with a marker and spray paint, that’s what you would do.

I did PEP I, with a roman numeral one, so if anybody came after me, they might want to say they were PEP 2. We became graffiti artists. And the next thing, when the music started going, you became a break dancer. Some people took it to the next level, where it became them. But our thing was giving the parties. We were producers. We gave the party, promoted it, found the venue, did all of that. And everybody came and became a part of it.

Did you disguise your records?

HERC: Yes, I had to cover it up. My father told me, scratch it up. So everybody don’t have it.

There were parties in the Bronx before August 11, 1973 at Sedgwick Avenue. What was different about that party?

HERC: Right now, the conversation for us, you’re going back. Some things I don’t remember. All I remember is: Behave yourself, smell good, and enjoy. That’s it. Don’t start no shit.

CINDY: He was playing music that you really didn’t hear on the radio. You only had one Black station playing songs. He would play what he thought was good. And people didn’t have this music setup in their homes. And for teenagers, it was something new to go out, where it wasn’t at somebody’s house or in a church basement. This was different.

How many people were there?

CINDY: Could have been 200, 300 people. People just showed up, to the point we had to tell people, you can’t go in and out. Once you go out, you can’t come back in. We had to figure out how to control it. It was just a party that we were giving for our friends and to raise some money. We weren’t depending on the money. It was just for me to have money for back-to-school shopping.

How much money did you make?

CINDY: Between $300 and $500. It was just a lot of change. It was too many quarters.

How often did you give parties?

CINDY: We couldn’t do it often. We had to go to school! We started doing it for special occasions, like a Thanksgiving party or maybe a Christmas party. And we did it when people said, when are you going to give the next party? It had to be supervised by our parents also.

Before hip-hop, musicians all went by their given names, like James Brown or Diana Ross. How did the hip-hop names get started?

HERC: I was giving guys their names. I gave them fame. If their name was Bo, I call them Bo-ski, so if the cops come looking for them, I’ll never rat them out. The cops looking for their government name. Not Bo-ski. And I told people, don’t start no shit here. Any problems, take it down the block. I look out for people. I called the party The Joint. And I called it “butter.” Like: Look fly, with your clothes. That’s butter. That means it’s nice.

You’re the one who first said “That’s the Joint?” That’s you?

HERC: Yeah. We used to go down to Delancey Street to shop for school clothes. ’Cause on Delancey they sold knockoffs. One spot on Delancey was called The Joint.

Like when I first heard “my mello.” It was at a club called Top of the Lane. And the guy was calling people “my mello.” And we stuck with that. That means you’re nice, you’re cool, no problem. That was it. I got it from Dixie. He used to run the spot. We played there, me and Coke took shifts. People were coming out of church on Sunday morning, and we were still playing.

You got stabbed at one party. What happened?

HERC: I didn’t blame anybody. That was it. So I backed off a little bit. I still played, and then [the movie] Beat Street came along, and they put me in that. I played myself.

Did you stop giving parties?

HERC: A little bit. Things was changing. I didn’t jump on board. People get older. It drew me into a shell. The mystique wasn’t there no more. Different generations came along and did their thing, you know what I’m saying?

CINDY: It’s just something that happened. And as he says, it gave people the opportunity to start DJing, because people still wanted to go to the parties, they were looking for a new home.

Then the record companies came along and left you behind.

CINDY: The whole industry profited off this. Vinyl was selling, and turntables. Now you needed two turntables. Fast forward up to now, it’s amazing that everybody can do a little 50th-anniversary thing. Television, the news, even little people in their neighborhoods: I’m going to do a 50th-anniversary block party. People coming up with T-shirts with Herc’s name. You’re not going to go after the little man on the street trying to make some money selling something like that. If it’s Nike or Adidas, go after them. But it’s amazing that everybody is finally getting a little something from it. You have the big rap artists, like Jay-Z or Ice Cube, but now everybody can do that.

How do you feel about your status? People in the know know who you are, but you’re not famous like some of the people who came later, and you didn’t get rich off it.

HERC: How do I feel about it? Give me an endorsement. Give me one. Just like weed. Weed is legal now. I want an endorsement.

CINDY: One? How about a few?

With any industry — could be the movies, comedians — the regular comedians who set the trends for the Eddie Murphys or Kevin Harts, like your Redd Foxx, your Moms Mabley — Redd Foxx didn’t make the money that Chris Rock or these guys are making, but they’re coming from that, an extension of that. When you think about it on that level, you see the transition and the evolution and where it came from. We’re still here. We’re not super rich, but we’re here. We’re still flying below the radar, but every now and then the radar picks you up.

For a long time you didn’t do interviews.

HERC: For what?

CINDY: I mean, he’s getting inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. There’s some things that don’t have a price on them.

How do you think your experience with addiction and recovery changed you?

HERC: A lot. My mother wanted to save me, but I was smoking crack. I went to rehab. Amy Winehouse says, I don’t want to go to rehab. I went. It worked. Amy Winehouse isn’t here. Monsignor O’Brien at Daytop Village, I give him a shout-out. I big-up Daytop.

Who is in your Top 5 now?

HERC: I’m always listening. My Top 5, I don’t know. “White Trash Party” [by Eminem], that’s one. That’s my shit. Or Millie Jackson, way back, saying “Fuck you.” Kid Capri, I give him love. Vinnie [Vin Rock] from Naughty by Nature, that’s my man. Betty Davis, Miles Davis’s wife.

Do you still DJ?

HERC: No, that’s over. And it’s not about me no more. I did my thing. Other people come in. The basic stuff came from me. The stew had been cooked already. Don’t break it up. Run with it. How long it lasts, go ahead. Everybody’s a millionaire now.

Were you disappointed when people took it and had a kind of success that you never had?

CINDY: For me, no. I’m happy. Because it’s about sharing. If we held onto this thing they call hip-hop now, and if someone tried to do something with it we interfered with them — we didn’t go to Brooklyn and say, We started this in the Bronx. We stayed in our lane. You had to stay focused, ’cause we were building something. We didn’t try to go to Queens or Brooklyn or Staten Island.

Everybody was doing something for themselves. That’s why it is where it is today. We just got something from Lula, the president of Brazil, saying they’re making August 11th to be Hip-Hop Celebration Day in Brazil. To me, that’s worth more than money. That’s me. We have the recipe, and you know how the recipe works. And just like you have different hamburger places and chicken places, all cooked in a different way that people like.