In the summer of 1984 when I started work on SPIN, which was then nothing more than a vague idea for a magazine about the music people I knew were actually listening to and the larger world we lived in, I had heard about rap, and I had read about hip-hop. But only in imported English magazines, particularly The Face, which from nearly 3,000 miles away knew more about this America than I did living 10 miles away. But I’d never really heard it.

I mean, I’d heard Grandmaster Melle Mel’s “White Lines” — who hadn’t, you couldn’t miss it/avoid it. At the time we considered that the Rosetta Stone of rap, although I often mentioned that Isaac Hayes talked through a few of his biggest songs in the ‘60s, and other, more knowledgeable people brought up the Last Poets. And there was Linton Kwesi Johnson… In 1984, rap was not the biggest thing in the world, and 99 out of 100 people couldn’t articulate the difference between the music and hip-hop. They were interchangeable. And white people did not really think much about it anyway. Yet.

Also Read

QUOTE/UNQUOTE

And I’d heard — or maybe I hadn’t by then, maybe I heard it later — “Rapper’s Delight.” I certainly hadn’t heard DJ Kool Herc.

I knew about the Bronx, where hip-hop started, because I lived in Manhattan. Which is connected to it! But in the late ‘70s the Bronx was, effectively, a war zone and often on fire. In the early ‘80s New Yorkers thought of it more or less only through the prism of the late ’70s. It was equivalent to Beirut. And about as far away in our minds.

None of that is racist. The Bronx was poor and dangerous, great swaths of it were burnt out or awfully dilapidated. Manhattan had everything. You did not need to leave Manhattan, except to safari to Queens or Brooklyn to eat some particularly authentic, exotic ethnic food. Or because you had a girlfriend or boyfriend who lived there.

So how did SPIN, by March 1985, when we launched our first issue — dated May out of insecurity, not knowing how long it would take us to do a second — become the first national music magazine to cover rap, and, for quite a while, the only one?

The short answer is: Generally our editors were aware of the music and familiar with the culture, which was, after all, taking place almost entirely under our noses, and specifically, a skinny white guy from New York who was, improbably, an expert on the music, John Leland.

I don’t remember who discovered John, it might have been me, it might have been Ed Rasen, our Executive Editor, who had never before for a day in his life been an editor, but who’d spent the previous decade being the most hardcore of hardcore war reporters — Beirut was literally, not metaphorically, his turf. One of us discovered John’s writing in the alt-weeklies, writing about music and especially lucidly and compellingly about rap, and groups and performers I’d never heard of. (Ed had.) Naturally we hired him to write for us, and later he joined as an editor. He knew things we didn’t know! A low bar, for sure, but upon which inspired ground great magazines are built!

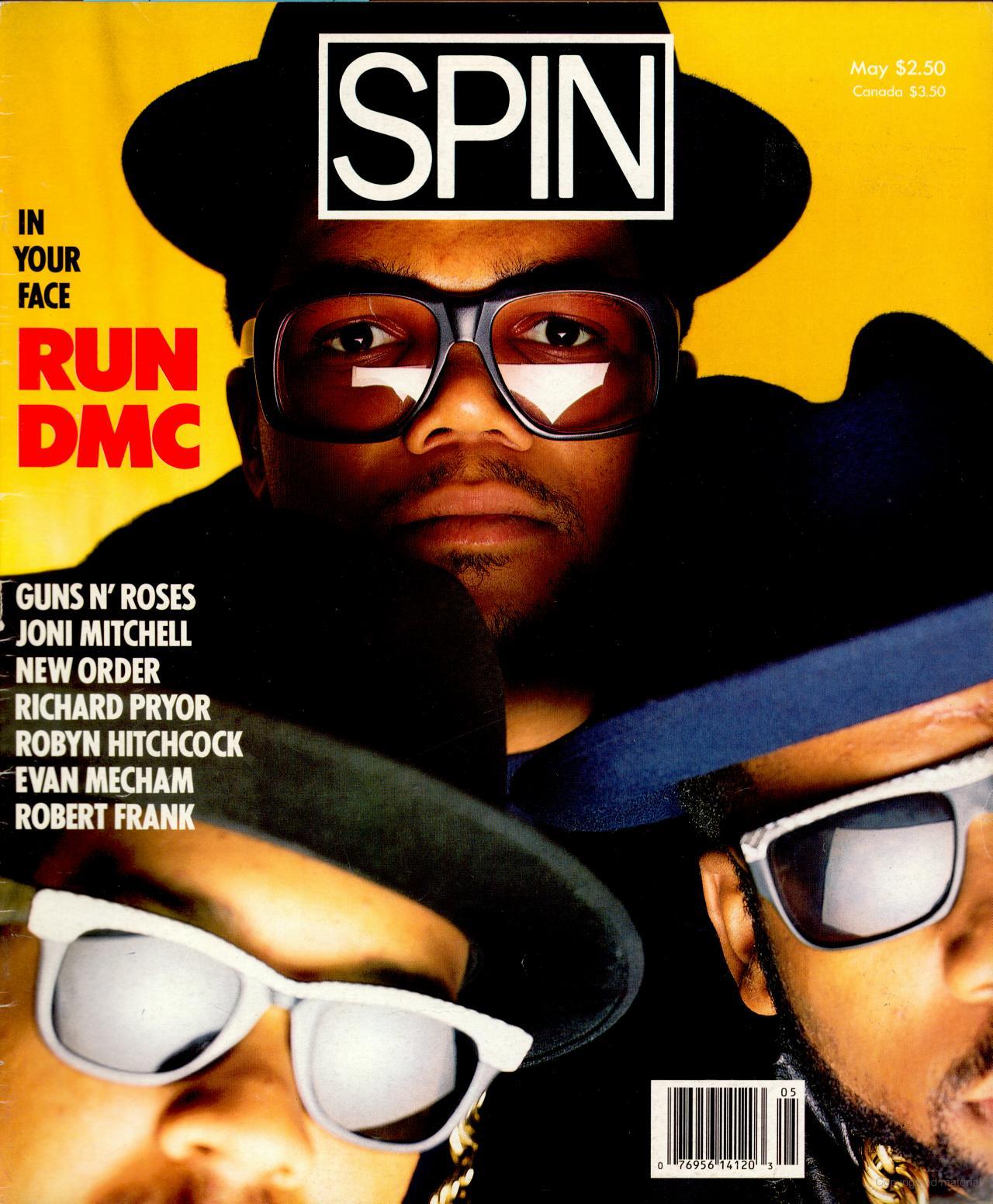

In that first issue, between interviews with unknowns like Bono and the Red Hot Chili Peppers, then crawling out of the placenta of their early careers, was a feature on Run-DMC, by Ed, probably cribbing from Leland. We called them the first superstars of rap. Their self-titled debut album had hit 500,000 sales, enough to be certified a gold record. Astonishing sales at the time for this (as far as most of America was concerned) fringe music. Their second album, King of Rock, the release of which precipitated our article, sold almost that many copies on its first day. “The video for their song ‘Rockbox’ appears on MTV, an unusual occurrence for most black groups, let alone rappers,” wrote Ed. Word.

In 1986, Russell Simmons, the co-founder of Def Jam Records (and brother of Run of Run-DMC, who were on the label) invited me to lunch. This was a big deal (for me) because Simmons was the big cheese in hip-hop. When I asked him why he called me, he said he wanted to meet the white guy who got it and was putting all these Black faces in a white rock magazine.

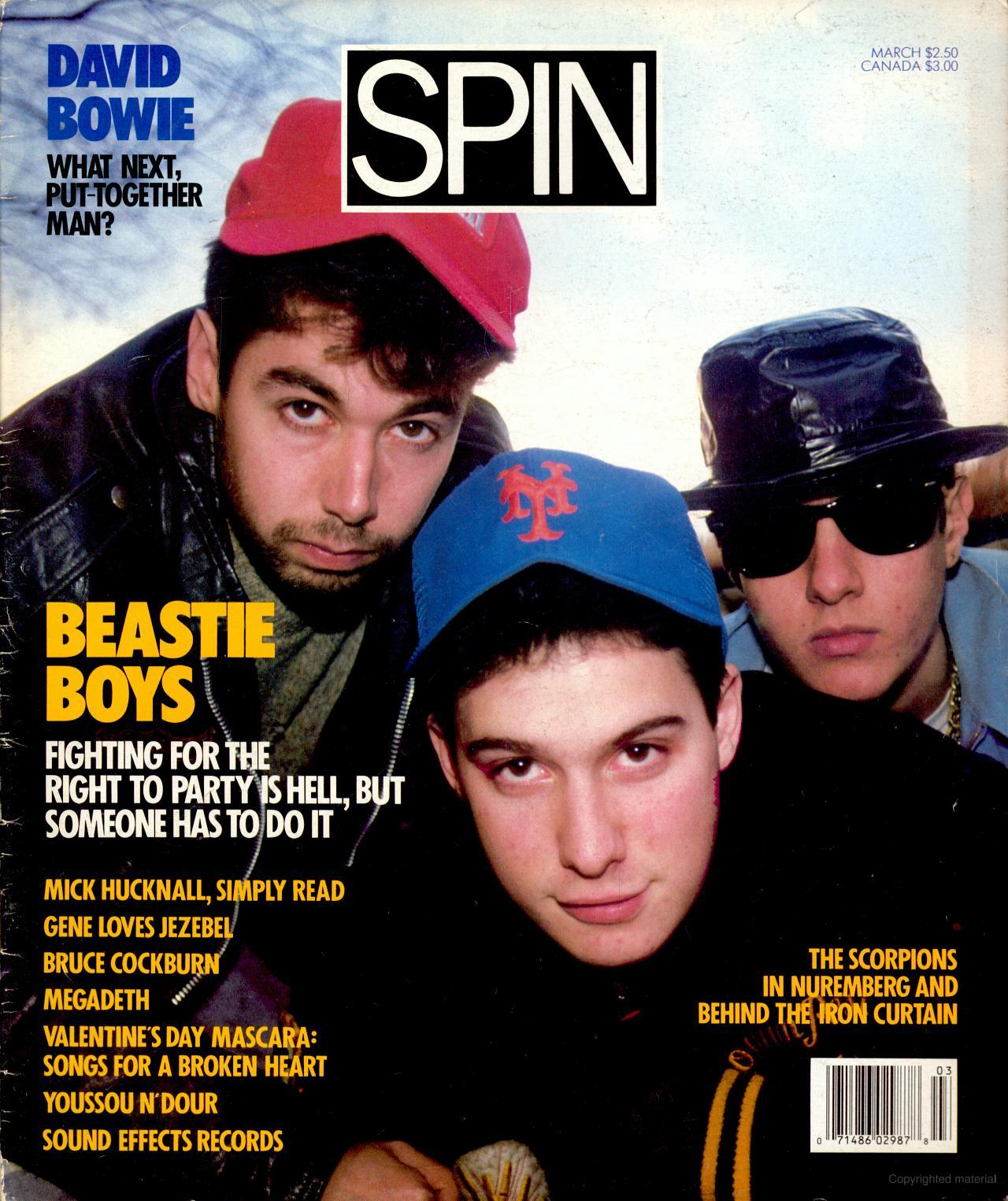

Our first rap cover was the Beastie Boys, in March 1987. By 1987 there were two things most people in America knew were there but on some level didn’t acknowledge — AIDS and rap music. Of course that’s not entirely accurate, but it’s also not inaccurate. America’s government was basically a stork with its head in the sand on AIDS — the President, Reagan, didn’t use the word in public meaningfully until 1987, and the NIH was talking self-serving, sanctimonious nonsense about it, and foisting a death sentence on sick people in the form of the only sanctioned medicine for HIV infection, AZT (until SPIN famously unraveled that story, FYI). And rap only drew mainstream and official attention as a menace — hounded by the Macbethian witches of the PMRC (the Parents Music Resource Center) and state prosecutors, with white America generally terrified of what they perceived as society-dissolving lyrics and aggressive, percussive, sexually threatening music.

Basically, the white, conservative establishment viewed rap and hip-hop as a less polite version of the natives are restless. And uppity. And I’m not exaggerating.

But the kids loved it! And that’s always the end, in the end, for the stuffy status quo. Young white people were discovering the exotic, dangerous wizards of rap on their own, but slowly, and then the Beasties, three white boys from New York, had the first bona fide smash, pop-chart-scaling, rap hit, “(You Gotta) Fight For Your Right (To Party)”, from the Licensed to Ill album. The wild and hyper video was a heavy rotation MTV hit, and the genie was out of the bottle. Rap had broken through the dam.

Few people in the press stood up for the Black shock rappers that got excoriated in the late 80s and, in some instances, prosecuted criminally under the sketchy obscenity law, but we did, relentlessly. I defended them on TV shows like Oprah and Phil Donahue, and regularly on the 700 Club, where I was known, derisively, as the house liberal, and in university debates across the country.

On one afternoon talk show, guesting with Luke Skyywalker from 2 Live Crew, then at the same level of public loathing as Osama Bin Laden would be years later, it was us against a couple of rabid conservatives, and they were goading him. I kept gripping his leg and saying, unheard on the broadcast, “Let me get this!” because I responded less emotionally than he did, and was shredding the hysterical arguments and the audience was clearly turning in our favor. Afterwards it occurred to me that millions of viewers had watched me grabbing an agitated Black man’s thigh for an hour.

On Oprah I debated that phony moralizer Tipper Gore, who started the PMRC ostensibly to ban offensive songs, but really to make her Democrat presidential-hopeful husband Al more palatable to middle America. (Thankfully she failed on both fronts.)

We loved rap and hip-hop at SPIN! We always took it seriously, including being critical of records or artists we felt fell short. We covered it profusely in our pages, we were a media sibling to its growth spurt. The Beasties came up to our office on Broadway and 62nd street and skateboarded through the corridors and hung out with us, sometimes for hours. I really liked those guys, everyone did, but eventually I had to ask them to stop coming because we weren’t getting any work done.

In the 12 and a half years I owned SPIN before selling it to, ironically, the hip-hop magazine Vibe’s parent company, I don’t think I ever consciously thought of us helping rap establish itself, although we must have helped, in a small way. In an appropriate way — we were meant to cover the culture, and we did, we just did our job. We were early, quicker to recognize the importance and power of the music and the impact of the culture. But it wasn’t bold, and I’m not even sure it was particularly insightful.

Looking back, I like the fact it wasn’t conscious. We weren’t making a grand statement, rap/hip-hop was on our pages because it belonged there. And it wasn’t that we were colorblind — we were — but more that we had good ears and good acuity and got excited. I’m very proud of that.