The fleet manager and bankroller of the American LSD revolution — an old man that my mother swears died long ago — tells me that there is no need to buy him a beer.

“I’m with the band,” he says. “My drinks are free.”

Here at this roadhouse in northwestern Oregon, at the Scappoose outskirts by the Columbia River, I pay for mine, and we turn for the stairs.

“Carry my beer?” he asks, passing his glass and taking the rail for the descent. “Long COVID’s left me a little unsteady.” He chuckles. “But I’m also drunk and stoned.”

“Still do acid?” I ask.

“I do mushrooms more often now,” he says. “I don’t take street acid because I’ve had the real pharmaceutical-grade stuff and it’s different.”

Meet 83-year-old George Walker: octogenarian psychonaut, O.G. Merry Prankster, logistics man to renegade novelist Ken Kesey, Indy race-team owner, sailor, Oregonian, kazooist, restorer of ancient buses, preserver of ancient memories, yachtsman to the stars, alleged beneficiary of David Crosby greasing palms to erase a drug case, elusive all-American playboy character in Tom Wolfe’s breakthrough Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, trust fund kid, preacher of eco-consciousness, squanderer of privilege, rethinker of privilege, descendent of America’s pioneers of filbert (hazelnut) orchards, nostalgist, casual cultist, son of the dead, father of the dead, spirit medium to the Beatnik proto-man, mythological maintenance man, anachronism, cautionary tale, and psychedelic financier of the very moment the American eagle began flying not east, not west, but directly over the cuckoo’s nest.

Walking with Walker is like walking with Where’s Waldo, clad as he is in the horizontal red and white stripes of an old-school surfer’s shirt — the uniform of the Merry Prankster psychedelic commando squad — but even in his wobbly 80s, he has the strong, weathered arms of a shipbuilder.

I hand back his drink as we stroll into the roadhouse beer garden, where instruments and sound gear are set up in a corner for the band he’s with. “We’re either called McCarthy Creek or Woodknot,” says Walker. “Or maybe it’s going to be Lost Creek.”

People are gathered here for a birthday within the Babbs family: a preeminent Prankster clan branching out from Ken Babbs, who served very early — ‘62, ‘63 — in America’s Vietnam misadventure before enlisting in his friend Kesey’s chemical chaos collective.

A few partygoers near me wear tie-dye, but a sip of wine and a remembrance that we are all God’s children helps my jaw unclench at the sight.

Walker says we’ll talk more after the show. He rests his beer under a Grateful Dead wall-hanging of a skeleton picking roses, and checks his instrument: an actual axe, wrapped in sparkly-silver gift paper with saxophone keys fixed along the handle, at the end of which a kazoo is taped to the underside. Blue electric lights appear to have been stuck to the blade, but in the indeterminate dimness of Oregon’s long twilight it’s hard to tell. The Axe-O-Phone, he calls it. Walker gives the kazoo a test blow. Not sure I hear anything.

Sitting at a corner table away from the main clan cluster, I drink and watch the other musicians — a fiddler, a hand percussionist, a couple of guitarists, a bass player — take their spots. Walker is the oldest. Three of his bandmates are in the dreaded tie-dye.

The younger of the guitarists sits for stretches without playing. He just stares out. And while the crowd grooves a little to the Californian-Celtic noodle-jam, swaying and smiling as they chat, I’m like that guitarist: sitting and staring.

Why he is motionless for so long I wouldn’t have a clue, but in my case it’s because this moment at the back of a roadhouse on the side of the Columbia River Highway is a timebomb of family history, of roots, of absence, of life-paths, of what it means to “go the wrong way,” of where doing “the right thing” leads, and of what-the-fuck-happened-to-America.

Maybe this sounds weird, but I want to ring my mother back in Australia.

“Mom!” I’d say. “You’ll never guess who’s standing right here in front of me now.”

The impulse strikes because the old man on kazoo is more than a lesser known but pivotal figure in the American apocalypse. He is also the wayward son of a family close to mine from late in the golden age when America was great and a small but cultured city in Oregon was heaven on earth.

It’s forever ago. It’s myth. It’s a Gordian knot of distortion, ignorance, nostalgia, and ideologically fixed visions of America. But all the same, my mom — who approaches terminal velocity in her Alzheimer’s plummet and does this in Australia, not having set foot in Oregon in more than 50 years — is still mad at George.

Later I do call her nursing home in Sydney, and when someone is available to hold the phone to her, most of what she says is slurred incoherence. Murmurs and breaths. In response to almost anything I say.

Until I mention that I tracked down George Walker.

“George was weak,” she hisses. “George came from a good family, but he went the wrong way.”

George Edward Walker grew up in sweet Eugene, Oregon, alongside my father and my uncle: all wealthy white boys born in the 1930s. Walker’s parents and my grandparents were close friends and fellow denizens of the country club and committee-lunch class of this progressive university town in central-western Oregon’s Willamette Valley.

Unlike my dad, spawn as he was of Wyoming immigrants, Walker was born a prince of Old Eugene — a society of propertied socialites, heirs to filbert fortunes, and patrons of worthy causes in a misted emerald world of orchards and the arts surrounded by southern Oregon’s hardscrabble laborer cultures in the logging, sawmilling, commercial fishing, farming, and other arduous industries.

His mother, Doriss Hardy Walker, was stock of Eugene’s finest bloodlines, cultivated from a fusion of two of the city’s 19th Century pioneer clans: the Dorisses and the Hardy’s.

When the Willamette Valley that cradles Eugene in its southern reaches was largely ethnically cleansed of the indigenous Kalapuyan people by way of disease, violence, and offers they couldn’t refuse, the pioneer clans became early major landholders, as well as preeminent in the law, the early development of the University of Oregon, and in filbert farming.

As Walker tells me with neither rue nor pomp: “I could have been a judge.”

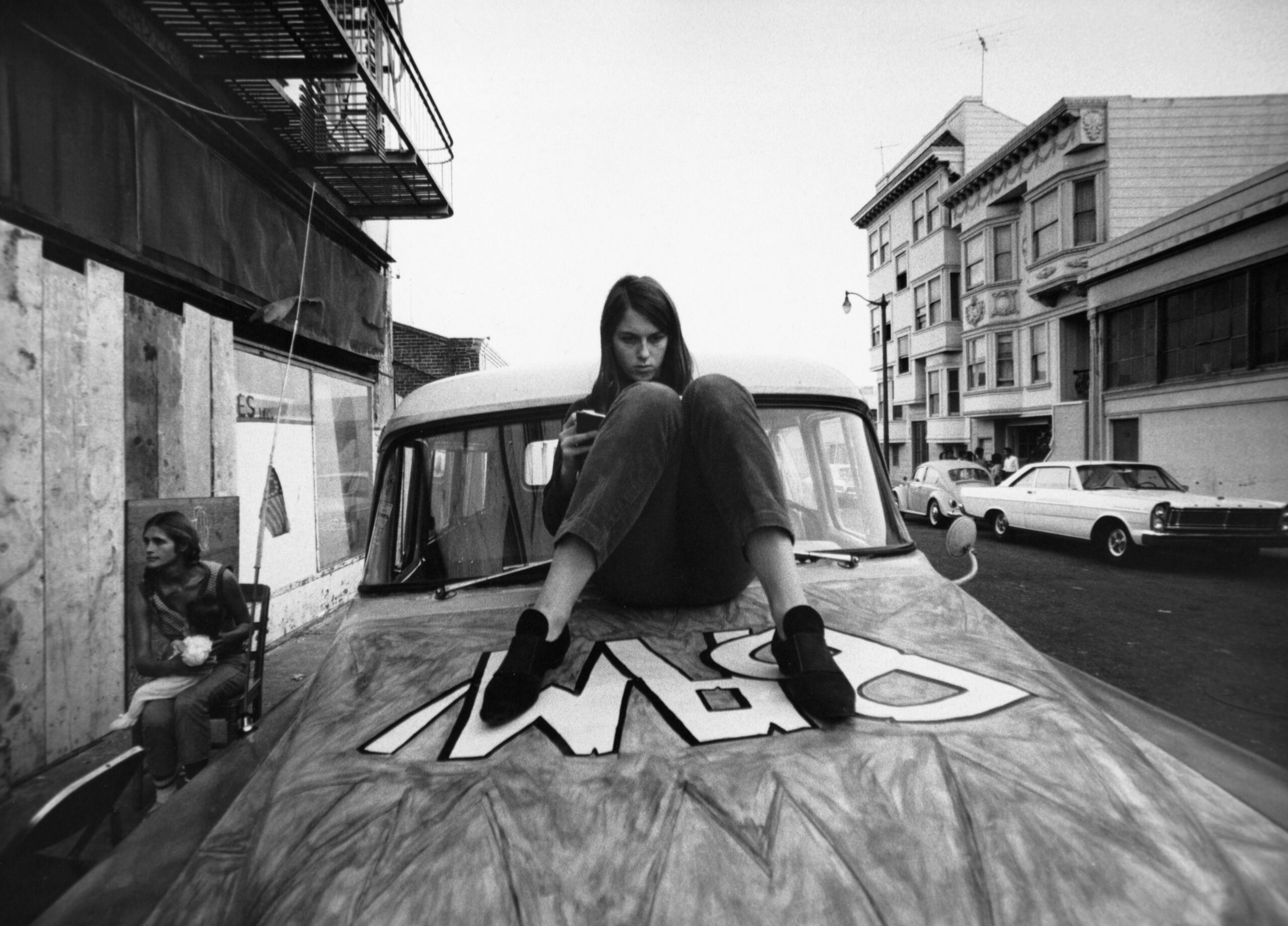

He made a sharp turn: dropping out of Stanford Law School, joining Kesey’s push for psychedelic social disruption, and spending thousands of his trust fund dollars to bulk-buy LSD in order to turn on hundreds at a time at the Acid Tests, advising the purchase of an old school bus for the Prankster’s now-mythologized 1965 road trip across America, joining Kesey in Mexico when the writer was on the lam from drug charges, and sharing a cabin there at other times with Neal Cassady, the whirling genesis of beatnik consciousness and star (renamed Dean Moriarty) of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road bromance, who had joined the Pranksters and driven the bus before ultimately collapsing and dying after parting ways with Walker.

And more, much more, decades more, leading to this point where George and I now chat at a bar about LSD, shrooms, and kazoos.

My establishmentarian father, who left the Emerald City not to spread the Gospel of Acid but to study at Notre Dame, serve in the Navy, and ultimately settle our family in Australia — must be turning in his grave at our drug chat tonight.

Except he’s not in a grave. He’s back on the main street of his youth, at least part of him is since the night my daughter and I clandestinely dumped some of his remains in a downtown flowerbed — ash voomfing up to speckle my kid’s teeth. What then remained of Phelan (an anglicized form of Ó Faoláin, an Irish name meaning “wolf”) I shook into deep, lush, forest cover near a semi-secluded Oregon sanctuary for white wolves.

Were Ó Faoláin still breathing, however, he’d without a doubt say, gravely: “George went the wrong way.” That was a maxim drummed into me from near infancy, along with “George was a follower” and “George was weak.”

On cue, my mother would jump in with: “It’s tragic. George came from a good family. Mr. and Mrs. Walker would go to the country club with your grandparents, and you have no idea what a big deal the country club was. They wouldn’t just let anybody in. George came from a good family, but he fell in with that Kesey and got into drugs, and it ruined his life. Kesey used him for his money. He milked him. He sponged off of him. They all did. George was weak. He even let people sink his yacht. They sank his yacht! It’s terribly sad.”

It was an habitual exchange between my parents Down Under. They’d be free-associating about the people and life they’d left behind, one thing led to another, and then bam! “Ken Kesey was a bad man;” “George Walker was weak.”

They sank his yacht.

My parents had exited the American apocalypse, settling in baking, barren, muted Australia when I was a small child, and from as early as I can remember through to the recent end of my long exile, George Walker was used by my parents as an example of what happens when a man — when a generation, when a whole goddamn country — lacks the spine to hold to the right path.

My parents went auto-play on Kesey and Walker not just to each other and to us kids, but also at dinner parties in bright, suburban Sydney, where there was no Ken Kesey. Where talk of the Walkers or other “good families” from far across the Pacific in misty, country-club Eugene meant nothing. Where guests would nod and politely agree that some George bloke they’d never heard tail of went the wrong way. Where we’d never have a yacht.

Our home in Roseville on Sydney’s North Shore was a shrine to a distant past, adorned with monochrome memories and mementos of my parents’ pre-Australia, largely pre-me, life: letter openers, old books, carvings from Oregon’s woods, and framed photographs of cocktail affairs and rhododendron gardens. A luminous Grace Kelly shines in one, and there was a swanky shot of my impeccably-dressed grandparents, Dr. and Mrs. Charles D. Thompson, of Eugene, Oregon, at a hotel restaurant in pre-revolutionary Havana. There was a portrait of my mother at her society wedding in Eugene. At the reception, George’s mother, Dorris Hardy Walker — or, as the Register-Guard called her in its coverage, Mrs. John M. Walker — assisted.

Visitors to our Sydney home would be walked in front of walls of photos. Cabinets, desks, tables, other pieces of furniture and ornamentations, even silver dining pieces, that had been shipped with us to Australia were pointed out.

Other times, during quiet moments, I’d look up at the walls of photos, or go through an elaborate wooden secretary, thumbing through decades-old business cards that I found from people my parents once knew, and feel in no world at all.

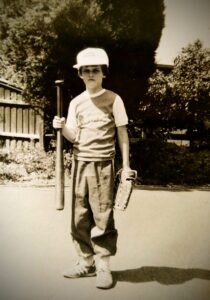

As a kid with an accent, as a “fuckin’ Yank poofta cunt,” I got used to fighting. During primary school (Australian for elementary school), I had on my case a mob of older boys who, two or three times a week over a year or two, waited for me on the walk home.

They could have been avoided had I taken the long way home, but no fucking way. I’d see four of five of these lads standing at their usual corner, grinning, and I’d keep walking towards them. As I got near, they’d start in with “fuck off back to Yankieland.” I’d tell them to get fucked. They’d spit on me, and then their leader would throw the first punch. I punched back and would then hit anyone I could get my hands on as hard as I could as many times as I fucking could while getting hammered worse from all directions until it got too drastic for a weekday afternoon in leafy Roseville and everyone split.

Before repeating tomorrow or the day after.

Post-clash, I’d continue down Bancroft Avenue, sore and agitated, turn the corner a block on, and enter our dimly lit shrine to a wonderful life in another time and in another place. Yankieland.

One afternoon I followed my father around the yard as he watered his beloved rhododendrons. The shrubs struggled with Sydney’s long, scorching summers, but lavishing water and attention on them connected my dad not only to the lush gardens of his Emerald City boyhood but to his father. For Dr. Charles D. Thompson served as President of the Eugene chapter of the American Rhododendron Society, and is even recognized by the Royal Horticultural Society of London for his development of a hybrid (to which Dr. Thompson gave my dad’s nickname: Skipper).

“If it was so good there, why did you leave?” I asked him. “Why did we come here?”

“Because Australia struck me as like America used to be,” he said. “Back in the ’50s before all the trouble got stirred up and all the drugs. When everyone got along, more or less. At least, when I first came here, Australia was like that; all the immigration and left-wing governments since divided the country and made it more dangerous — like America became in the ’60s.” He sipped his beer. “And all the drugs. They destroy people. They did a lot to destroy America. Before all the drugs, America was a great place.”

Oregon now is awash with junkies. Personal use of all drugs is decriminalized, and multitudes of shattered slaves shuffle and tweak the streets and line the riverbanks. As they do in many towns and cities of America, with its 100,000-plus annual death toll from overdoses and a per capita rate beyond all other developed nations.

Why this nation is so singularly hell-bent on getting hammered, on taking edges off, or putting edges on, bent on better living in all directions through chemistry, has a thousand answers and no answers, but as for whom to blame, Ó Faoláin never missed an opportunity to name another ’30s-born lad-about-Eugene: Ken Elton Kesey.

“Kesey was a bad man,” my father said, yet again. “A great writer but a bad man. He used his influence to lead people the wrong way.”

“Like George Walker?” the young me had learned to say.

“Like George Walker,” he said. “Matt, I want you never to be a follower. Be a leader.”

“Like Ken Kesey?”

“Don’t be a smart alec.”

Now with my father fertilizer, my mother in terminal shutdown, my brothers having cast their lots Down Under, only I — the youngest son, the most wayward, the most inclined to the “wrong way” — have dragged myself free of the Antipodean torpor and not only “fucked off back to Yankieland,” but right to the heart of it all: Oregon.

Where now I sit out back of a Scappoose roadhouse at a stranger’s party as a guitarist stares into space and the young have become old. Where now I still can’t hear George’s kazoo in the mix, but I can see the old man still standing, still ready to meet a stranger to talk.

In a break, Walker smiles as he recalls my grandfather. George says that after his father died in ’61 my grandfather was a rock to his mother. “Charlie Thompson,” he says. “Of all my parents’ friends he was my favorite: kind, and generous, and friendly. A likeable, good guy.”

My grandfather is someone I knew only from stories and memorabilia: the photos, along with carvings and fishing lures that he’d made to maintain dexterity for performing surgery. The closest thing to being in his presence that I remember came after my dad one day yanked me from primary school to fly with him to America, to Eugene, for old Charlie’s funeral — where there was no presence at all: just a vacated corpse in a box.

But talking will have to wait. Walker has more sets to play, and I have a three-hour drive south beyond Portland and the Willamette Valley, so we adjourn.

George is ailing when we resume. He’s had two confirmed cases of the plague and feels Long COVID is taking him down. “I wake at night and feel like I’m on fire,” he says.

Hit also by chronic fatigue, vertigo, ringing ears, pins and needles, and a cognitive haze, Walker says he is low.

“I’ve got a lot of depression. Days where I don’t feel like doing anything at all, so I don’t.”

His restoration of a 1937 International school bus — a way to keep the Prankster dream rolling — has halted.

“I seriously question if I’ll be able to finish,” says Walker.

Kesey, the great Chief of the Prankster dream, has been dead more than 20 years. I ask if Kesey ever shows up in his own dreams.

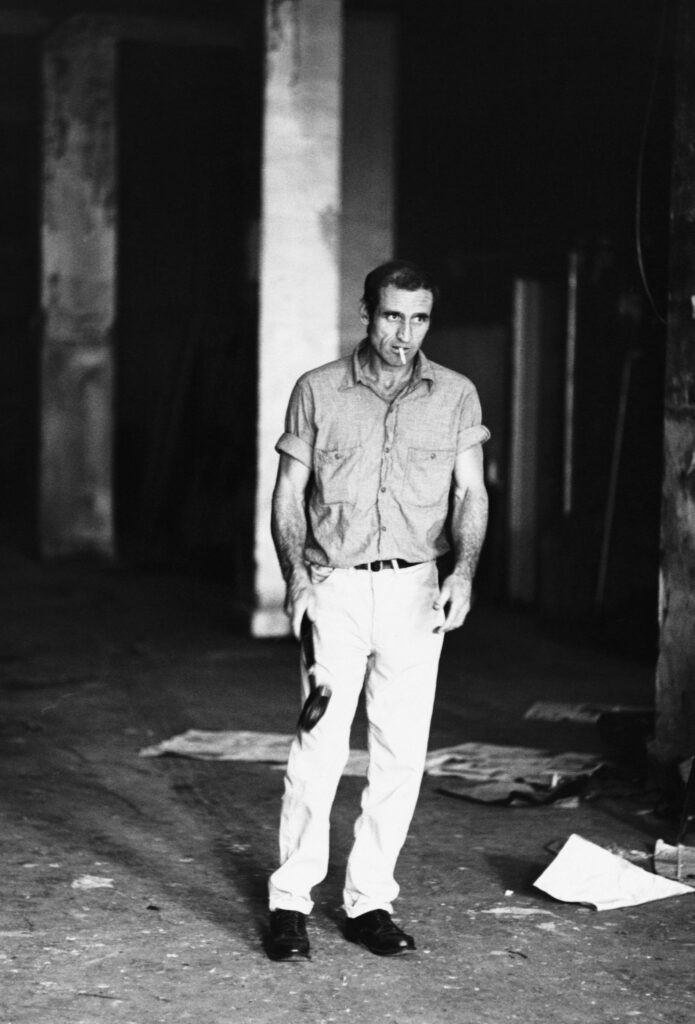

“Never anything really personal,” says George. “I hung around him a lot. I was part of his posse: helping him do stuff, participating and everything. But we were never really close. In his mind, I was a minor character in what he was doing, and probably not somebody that he felt was important to communicate with after he was gone.”

The person who has communicated the most from the other side, Walker tells me, is Neal Cassady, the unhinged hammer-juggling, pill-popping, go-go-go Colorado ex-con flibberty-jibbering, hyperwired macho meteor of a man who enthralled and inspired the beat writers, most notably Jack Kerouac.

With Cassady’s nose for transcontinental narco-intellectual ferment, he’d found his way into the Kesey scene, was at the wheel for most of the legendary 1964 bus trip, and the next year was part of Kesey’s entourage in Mexico, where the Chief had fled in the face of possible prison time on a Californian marijuana charge. After eight months, Kesey returned to face the music, did a half-year stretch, and then settled, show over, with his family about 12 miles southeast of Eugene. In the Prankster aftermath, however, Cassady kept rolling, including back into Mexico twice, with Walker, sometimes for months at a time.

“It was absolutely glorious,” George says, chuckling a little. “Neal was great company. I loved hanging out with him. He was always scheming, and plotting, and conning — all the time — I thought it was amazing. He was constantly verbalizing his thoughts, and it was really hard to follow because he changed his mind constantly. He didn’t have a lot of confidence in what he was saying, but at the same time he was supremely confident. And so he would start off with extreme confidence and great knowledge about telling you how it all was. And he wouldn’t finish a sentence before he would have to start retracting it and modifying it and making sure he got the parts of it that were wrong right, and then explaining how it was that what he thought had happened hadn’t happened. And all while also explaining what the people in the back of the room were thinking about. It would go on like that endlessly.”

A rotating cast of friends, associates, and lovers came through Mexico, sometimes harmoniously and at other times necessitating contingency plans. On one such trip to San Miguel de Allende, Walker says, “Cassidy brought his part-time girlfriend, Ann Murphy, who was a gigantic pain in the ass — about half the time –- because she was psychotic as hell and neurotic and freaked out and just on a ramp. The rest of the time she was sweet and nice. You never knew how she was gonna be. So we had an extra ticket — this is back when airline tickets were like subway tokens: drop ’em in and you go. We had an extra ticket to send her home anytime that we couldn’t stand her anymore.”

Another arrival in Mexico was Gordon Lish, a literary editor taken with Kesey and the wild world of the west coast writers. It was Lish who took the unremarkable drafts of a short story writer from Oregon named Raymond Carver and sliced them down with such artful severity that he created The Raymond Carver, celebrated master of minimalism and understatement.

Walker says that towards the end of their last time together in Mexico — a four-month stretch from 1967 into 1968 — he was able to help Cassady ease way back on amphetamines: “I got him to stop taking speed most of the time. To where he could take it occasionally instead of being constantly strung out.”

The proto-beatnik hero grew more settled over those months, Walker says, but then they went their separate ways: “Unfortunately, I’d abandoned him in favor of the ladies. And he took up with a woman who I think ended up being the death of him.”

In February of ’68, Cassady was found collapsed by railway tracks in San Miguel de Allende and taken to hospital, where he died. He was 41.

I ask Walker if Cassady had seemed like someone who was soon to die.

“He thought so,” says Walker. “He tried several times — well, he tried on the idea. He definitely had a death wish. But I didn’t think he was going to die. But he wasn’t particularly well. He had lived more in his almost 42 years than most people would in a dozen lifetimes. And he was a very strong and serious believer in reincarnation and past and future lives and the eternal nature of the soul. He wasn’t at all afraid of death. He figured he’d done enough for this time around. He was ready to do another round.”

Towards the end of that year, 1968, Tom Wolfe published The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, which recounts with vivid immediacy what had by then dissolved. It sold well and kept selling, and over time Wolfe’s mythopoetic saga of Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters was absorbed into American legend. It became a quest where every haphazard, grungy stage of these thrill-seekers’ journey was now loaded with immense symbolic power. Perhaps as Lish made Carver, Wolfe made Kesey.

Wolfe, with his writing, raised a burned-out novelist and his former posse into immortal figures. I ask Walker about the book and its influence.

“When it first came out it was kind of a splash and people read it — it was a big thing — but it didn’t translate to instant fame,” he says. “But more and more people read it — it’s slowly grown for decades — and I’m more famous now than I was back then, by far. People relate to Tom’s book.”

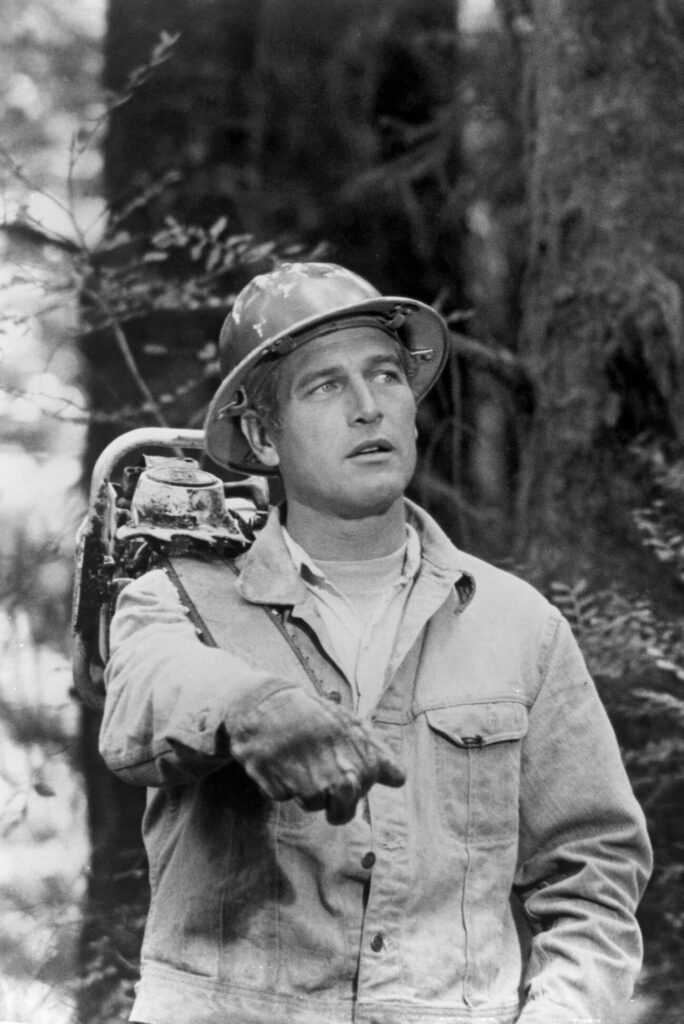

In 1970 Paul Newman directed and starred in a film adaptation of Kesey’s second novel, Sometimes a Great Notion, which screened in theaters the next year (and became the first movie shown on HBO when the pay TV network launched in ’72).

Sometimes a Great Notion was shot in Lincoln County on the Oregon coast where “Newman and I got into a backroad car race,” says Walker. “The day we were there they were doing two different locations on two sides of the river — up river a few miles. There was no bridge there, so they had to drive down to Highway 101 to cross the river and then go back up the other side. And we ended up in a race. Paul had a rented Corvette, and I had my Lotus. I could have beat him easily, but I was afraid that he’d get killed if he tried to catch up with me, so I let him pass me,” says George with a chuckle.

For much of the ’70s, Walker then lived in Hawaii, sailing the islands for charter in his 65-foot ocean racing schooner, Flying Cloud, and catering to musicians and other stars.

“By that time, Wolfe’s book had been around enough that people kind of knew who I was — so I had some kind of credibility. Most of the rock and roll people who came to Hawaii I took sailing. They sought us out and I was up for a good time,” says Walker. “I got to be good friends with Peter Fonda. That was right after Easy Rider, so he was suddenly real famous. I also hung out with David Crosby a lot.”

Crosby and Walker shared a love of antique sailing ships. In late ’71 or early ’72, Walker says, he was on Crosby’s boat when it was moored at Newport Beach, California, getting work done, when police raided it and found marijuana.

“David wasn’t on the boat at that moment — he was with Graham Nash up in Los Angeles. They came back about midnight, and the cops were waiting for them too. Of course they found half a ton of weed on David, so they busted him too. But we partied in jail for the night, and they let us out in the morning.”

I ask what happened at court.

“That was bizarre,” George says. “My attorney told me that when he went to the next hearing, he appeared in court and said, ‘I’m here for such and such a case, but I don’t see it on the calendar.’ And the court clerk says: ‘I’m sorry, we don’t have a case of that number.’ My attorney was pretty sharp, saying: ‘Oh, my mistake. Thank you very much.’

“And that was the end of it,” says Walker, chuckling. “My attorney said to me: ‘I’ve seen cases dismissed but this the first I’ve seen disappeared.”

“How did that work?” I ask.

“David told me later that it cost $30,000 to make the case disappear.”

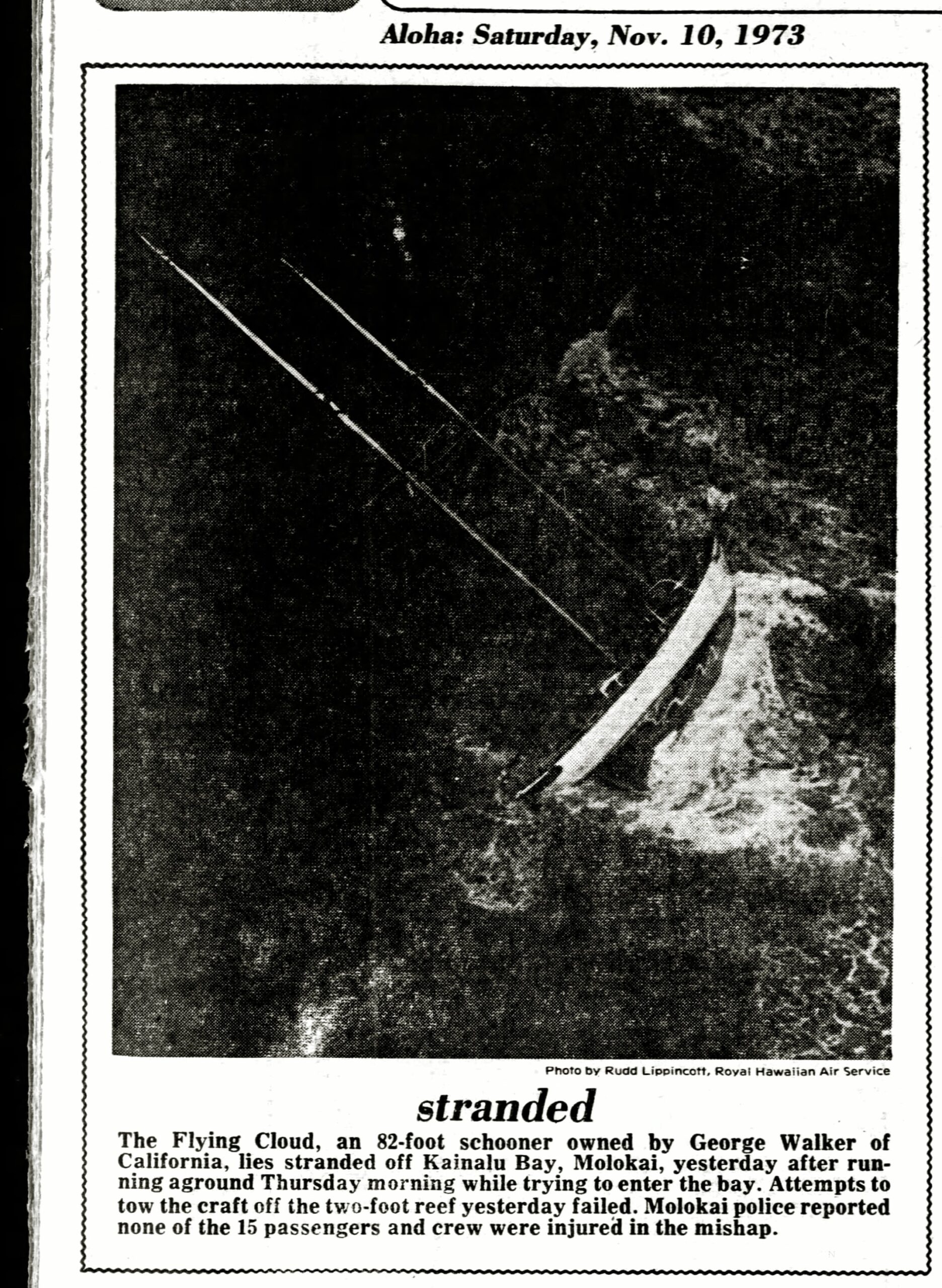

After someone wrecked Flying Cloud in 1973 (Mom was kind of right!), George got a settlement for it, stayed in Hawaii through much of the ’70s, working other people’s boats, and then formed an Indy car company, running race cars until the early 1990s — a venture which ended with him broke.

“What was it like being broke at that age?” I ask. “Dark night of the soul?”

“I don’t understand the question,” says Walker.

“Was it a grueling time?”

“I figured out stuff to do. Some of the stuff I did I’m not very proud of, but you have to be pragmatic and do whatever makes you some money.”

“Like what?” I ask.

“Oh, I dealt some drugs and did stuff like that. I had some friends by then that knew people who were smuggling from Mexico. I’d rather not go into it.”

I bring up the Eternal Recurrence, Nietzsche’s thought experiment in which he asks us whether we would be devastated or overjoyed if we learned that our fate was to live our lives again and again exactly as we have lived this life.

“There’s stuff that I did that I don’t even want to talk about that I look at with chagrin and wouldn’t do again, and would prefer that I hadn’t done,” George says. “I have not always been a good person. I’ve done terrible things in my life, as have most people.”

Walker says that about a year after Cassady died, his late friend began coming to him in dreams and directing him to read the transcriptions of Edgar Cayce, a professional clairvoyant and spiritual instructor who died in 1947 but founded an organization, the Association for Research and Enlightenment, which continues.

“When he was talking about it while he was still alive, I never really gave it much credence,” says George, but the dead Cassady and his instructions opened his mind to the truth of reincarnation.

Walker had a son who died several years ago after suffering strokes. I ask George what it was like for him when his son died.

“It was no big deal to me,” he says. “I mean, I was sorry, you know. I’d like to have done more with him. But again, it’s this whole thing. Even before I began to understand birth and rebirth and reincarnation, even before I entertained that idea as a reality, I was never troubled by death. It didn’t bother me when my dad died. It didn’t bother me when my mother died. It didn’t bother me when my friends died. They died: bye, move on,” says Walker. “I have often thought there was something wrong with me that you’re supposed to feel all this grief, and I never felt grief about people dying.”

“Okay,” I say.

Walker continues: “It just doesn’t bother me. They move on. That’s the end of that chapter. It’s like anything else. Things come and go. People come and go. Stuff comes and goes, lives come and go. Everything comes and goes. It’s just the way stuff is, and, and to feel grief about it? You’re not feeling sorry for the person that died. You’re feeling sorry for yourself. That’s the reality. Everybody that feels pain — they feel pain because they’ve lost. It isn’t like the person that died lost. They’ve lost; they’ve lost friends. It’s a selfish thing. Grief is a selfish thing. I’m selfish enough about enough other stuff, and I don’t need to be selfish about that too. So, no, I didn’t particularly feel grief when my son died.

“How old was he when he died?”

“Fifty? I can’t remember exactly. 52, I think.”

My parents’ brainwashing of me about Walker is stuck in my head, and I tell George about the relentless head-trip: that he was a follower; he was weak; he went the wrong way.

“I still get told that,” says Walker. “But I had fun.”

In coherent moments, my mother has lately been reporting that my dead father visits her, asking her to come with him.

In our most recent call, she was once again incomprehensible until I mentioned that I’ve been talking to Walker.

“George Walker died,” she then says — with perfect clarity.

“He’s alive. I’ve been talking to him.”

“George Walker died.”