“I think your friend is schizophrenic.”

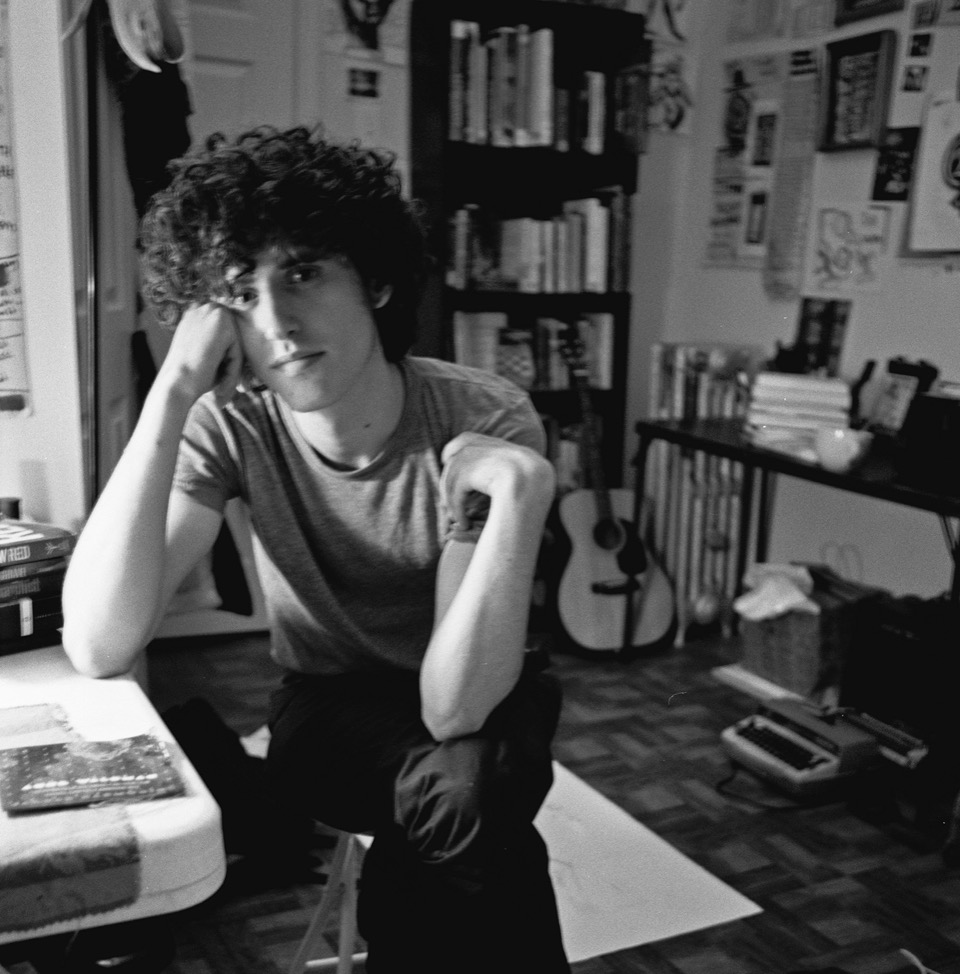

That’s how Connor Grant recalls Sean Ono Lennon’s reaction, in 2016, to hearing the delicate sprawl of Zack Rosen’s music for the first time. The photograph on my desktop of Rosen is appropriately and fractionally out of focus. It is the photograph of a young man who would drop to his death from the roof of a high rise building in 2019.

With the posthumous release of Rosen’s album SYZYGY this past March on Lennon’s Chimera Music label, SPIN spoke with Lennon and Grant about the troubled and poignant legacy of a unique artist.

Grant, who played guitar with Lennon’s The Ghost of a Saber Tooth Tiger during the Midnight Sun tour and works with Lennon as a studio engineer, was skeptical. He had known Rosen since 2013, and while his behavior had been eccentric, it hadn’t struck him as evidence of mental illness — or he had not been prepared to admit it, yet.

Also Read

THIS IS AMERICA

“I wondered if he was developing some sort of condition, but I had no point of reference,” Grant says. “But Sean recognized it immediately, and for the next three years, Sean really guided me through some tough situations, because I didn’t believe him when he first told me… I don’t know how I would have navigated my relationship with Zack if not for Sean.”

Lennon explains, “Schizophrenic people often have a unique relationship to language. His imaginative use of words and chords made me think he might’ve been suffering from a mental illness. But that’s the thing about mental illness — it is incredibly complicated, and there are many sides to it. In Zack’s case, I do think his incredible creativity and originality were connected to that disease, very much like Syd Barrett. But I am also certain Zack would have been a brilliant songwriter if his illness had never manifested.”

And SYZYGY is an extraordinary album, certainly one with references to Nick Drake, Syd Barrett, Brian Wilson, and Bob Dylan. Rosen was an obsessive student of Dylan, but as the title alludes, the album also embodies an attempt at psychological reconciliation.

In Aion, Carl Jung defines the reconciliation of the syzygy—or the male/female images of the unconscious—like the integration of the shadow aspect of the self, as part of the process towards wholeness. Jung writes of the risks, “For the syzygy does indeed represent the psychic contents that irrupt into consciousness in a psychosis (most clearly of all in the paranoid forms of schizophrenia.)”

Lennon adds, “I think there is a long history of creative genius mingling with madness. It’s hard to define, but it can be clear when you see it. There is a certain vibrance to Van Gogh’s greatest work, a certain freedom in the songs of Syd Barrett, that seems to have come from a creative source that was less bound by what you might call societal constraints.”

Grant recalls the comparisons being made: “The Syd resemblance was just in how sweet his voice was and also how sweet the songs were – they were very deep harmonically, they were very complicated to analyze, but not to listen to. But they had this innocence to them as well.”

Grant was born in Chicago but found his eclectic musical community in Brooklyn, busking in the subway, and running a converted church as a hotel in Williamsburg. In 2013, he assisted Lennon and Deerhoof drummer Greg Saunier, who were recording as Mystical Weapons. At the same time, he worked with Yoko Ono and GOASTT. Grant was also auditioning musicians for his own project, Tongues Unknown. In November that year, he met Rosen, brought along as fill-in bassist by drummer Jason Burger. “The day I met Zack,” Grant says, “changed my life forever.”

“Zack, around that time, was starting to lose a lot of his gigs,” he continues. “It seems like the schizophrenia, his illness, was just starting to really take over, right when I met him. Jason was 10 minutes early, and Zack was an hour late. He showed up. I got the real thing right out of the gate. He had a book bag with 30 paperbacks in it, and food, snacks and shit just stuffed into every pocket of every gig bag. And he had a whole bunch of energy drinks and caffeine, and he was so enthusiastic. I started laughing. He was just shambolic, totally oblivious to us waiting for him. At the time, I just took it that he was an eccentric dude, and he was. I just caught him right on the cusp of the person he was and the person he became…There was always that part of him. He made you laugh. He was so curious and enthusiastic and eccentric.”

Almost immediately, Rosen moved into Grant’s converted church loft. Touring with Lennon and the GOASTT meant Grant was absent for some time. When he returned, it was during the first of several of Rosen’s disappearances. “He wasn’t there anymore, but all his stuff was there. When I went into his room, it was like a library of books that were all marked open to a page or a page turned down, on the floor, and he was a voracious consumer of information…A lot of poetry, a lot of anarchist literature…He was passionately involved with Occupy Wall Street.”

Activism was something Zack Rosen shared with Brian Jackson, keyboardist and flautist for Gil Scott-Heron, and bassist Devin Hoff, both of whom appear on SYZYGY. Eventually, Zack would return. It was only later that Grant would learn that some of these disappearances involved hospitalizations and arrests.

In 2016, Rosen revealed to Grant that he had been writing songs: “I probably played them 100 times on a loop, and I said, ‘Oh my God, Zack’s a genius, I hardly knew he even played guitar.’” Grant was determined that the world should hear his friend’s music, to share in its swirls of inspiration. And yet, this was set against the background of Rosen’s illness, what it took from him, psychologically and physically. Rosen’s condition included a syndrome known as anosognosia; essentially, this is the inability to perceive one’s illness. “Being involuntarily hospitalized, especially when you don’t believe you are sick, is essentially being sent to jail. And it was Zack’s worst nightmare.” So read a section of Rosen’s memorial.

The syzygy that Rosen struggled with expresses itself across the two distinct sides of the album. Grant describes it: “His singing voice gives an insight into the person he was. He genuinely cared about everybody, wanted everybody to be equal. That was a huge part of his identity…kind of utopian.” Here, Grant hesitates, considering the depth and strangeness of their relationship. Rosen was a prankster, a philosophy student, “always 10 minutes away” wherever he was, whenever he was late, sometimes lost in his preoccupations, not least in his admiration for Bob Dylan.

Grant is pensive. “His voice…There’s a pretty noticeable change in his voice from Side A to Side B. The first side is, to my knowledge, right when he began recording songs. This was right around the time that I met him. Side A is his first crack at songwriting. Then he did that thing where he disappeared for a long time, and every time I would see him, if a year or two went by, he was entirely a different person.”

“There were four years or so between the Side A recordings and the Side B recordings,” he continues. “The sequencing of the tracks became chronological, which normally would seem gimmicky to me, but it made sense this time. It told his story a little bit, in my mind. Everything he did was so intense. He started smoking multiple cigarettes at a time, in short intervals. He would smoke four or five cigarettes at the same time.”

All of this took its toll on Rosen’s voice, Grant recalls: “Toward the end, he had a lot of trouble singing.” In the beginning, Rosen had been reluctant to record multiple takes of his songs. Toward the end, he struggled to find a point of completion. “Zack never thought it was right. He was always just chasing the dragon, if you will, of his songs. He started changing the words to songs that had been around for a really long time. I think it was the different things he was struggling with in his head…There would be times when, you know, I don’t think I was talking to Zack, and then he would kind of come back, and I think some of the ‘critics’…I think some of those, uhm, ‘inner dialogues’ he was having led to the songs needing to be changed…”

The last time Rosen and Grant played together was for a Nick Drake tribute at Gold Sounds in Brooklyn. Amidst rehearsals, Rosen disappeared again. Grant is somber: “He just decided he wanted to get out of New York, and he left for California on a bus, and he was calling me about rehearsals, but he was canceling these rehearsals or saying ‘Hey, I’m going to have to back it up a couple of hours, if I can make it, but I’m in Brooklyn. If I can’t do today, I can do tomorrow.’ And I knew he was on a bus to California.” Grant would try to keep his friend on the phone by pretending that he couldn’t remember certain Nick Drake songs, and Rosen would sing them.

“He definitely sounded kind of…at peace, y’know? Singing songs to me on a bus. But at the same time, I knew it wasn’t a healthy thing that was happening. My goal back then was to finish his record and put it out as soon as possible, because I just had a weird sense of his of his enthusiasm fading, and the songs were so great and I thought it would be a positive force in his life if they got out…So I wanted him to see it, for us to put it out as soon as we could.”

But Rosen returned, and they performed at the Nick Drake tribute. Recording sessions were scheduled for the SYZYGY material, but Grant was increasingly uneasy. “The last session we did was days before he left us, and I just had a really bad feeling, those couple of months,” he says. “I just felt that he was, you know, helpless. He seemed distant, uncomfortable, and sort of defeated.”

He recalls the morning when he learned of Rosen’s death: “I was at the studio. My phone rang when I saw it was Zack’s father. I was always friendly with him and his wife, but, by that point, in light of the circumstances, we had grown unexpectedly close; a Saturday morning phone call felt off. In spite of the growing pit in my stomach, I answered, and from there it’s a blur. Through a jumbled mess of denial, confusion, unwarranted guilt, and everything else I couldn’t process, I was told, “It was the disease that put Zack over the edge.”

In shock, Grant locked himself in his room at the studio. “I don’t remember anything except being in there for a long time,” he says. “And when I came out, Sean was patiently waiting, ready to listen, and I’ll forever be so grateful for that.

What is SYZYGY’s position in the grief process?

“I didn’t give myself the space to mourn,” he says. “I was listening to his voice every day, and all the B-roll of our conversations. I had more Zack in my life than ever, but he wasn’t there anymore…Deflect is the right word. I thought that was my way of processing. I thought I would get closure, doing what I thought was right by Zack. I was really playing kick the can…And I’m not done with Zack’s music. I’m so excited about the release, and so grateful to Sean for taking a leap of faith on an unusual situation. I don’t feel like there’s going to be a moment of closure, but my hope is that as many people hear his music as his music deserves.”

Sean Ono Lennon concurs: “When I heard Zack’s songs, I knew immediately I wanted to put them out. All I wanted was for people to have a chance to discover what I believe are amazing songs.”

Zack’s Rosen’s SYZYGY is available now, from Chimera Music.