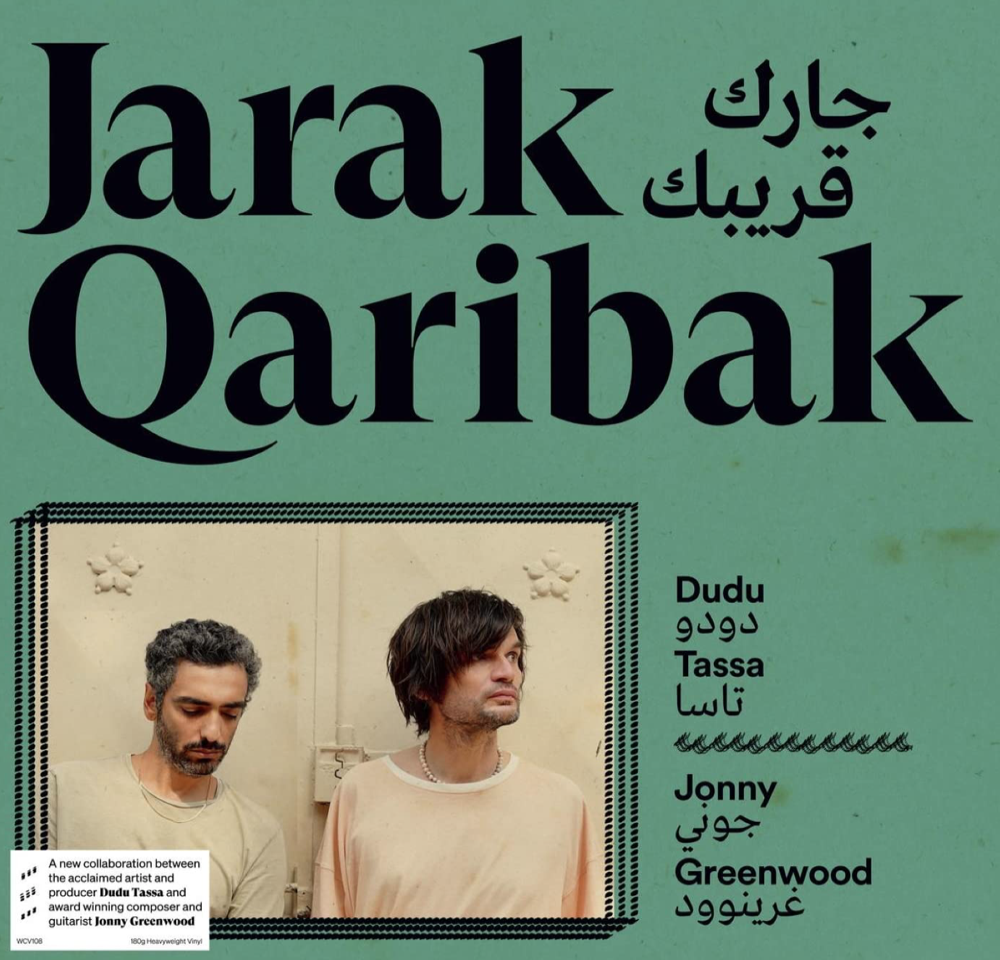

The path to Jarak Qaribak, the captivating new collaboration of Arabic-language love (and out-of-love) songs led by Israeli rock star Dudu Tassa and Radiohead guitarist/film composer Jonny Greenwood, can be traced back about 20 years ago to a café in a town in northern Israel.

“I was playing in a restaurant,” Tassa says from his Tel Aviv home, with manager Or Davidson translating as needed. “It was really when I was starting my career. And the owner of the restaurant said, ‘You know, my sister is married to Jonny Greenwood.’ And I said, ‘Yeah, yeah. Sure, sure. Yeah, okay.’ But after a few weeks, she introduced Jonny to me.”

A magical musical meeting? Not exactly.

“Because my English wasn’t so good, I was a little bit unconfident in myself,” he says, laughing about it now. “It’s not like in Hebrew where I can immediately connect to someone. But also, it was Jonny Greenwood.”

Tassa may have been shy with the star initially. But over further encounters and communication in the course of a few years, as Tassa’s own prominence grew as well, they connected enough that, in 2009, Tassa got bold enough to send Greenwood a song.

“I sent one of my Hebrew songs that I had recorded,” he says. “And Jonny recorded the guitar to it.”

With that, a door was opened. And though it took a while, the full collaboration that grew was well worth the wait. To be clear, Jarak Qaribak is not Radiohead-Rocks-the-Casbah. Nor is it a Tassa rock album with Greenwood as guest star. It’s a loving, respectful, and deeply personal tribute to the music and culture of the Mizrahi, the Jews who lived throughout the region, from North Africa to Egypt and Yemen along the Red Sea and to Iran and Iraq, for centuries.

“It really happened very naturally,” he says. “I’m coming from the Arabic music that I know, and Jonny comes from rock. But we each found our place in a very natural process. It was just a thing that needed time.”

Greenwood did have a head start, having been exposed to a good deal of Arabic and Israeli music via the family of his wife, visual artist Sharona Katan. But he was eager to learn more.

“Jonny is a huge, huge artist, but he is very curious,” Tassa says. “He was very curious about the Arabic music and the things I did. And that’s what made us both try to explore that music and to do something together.”

The roots of the album, though, go back far beyond their café meeting, well before either of them were born. As Tassa looks back, he starts to sing a line from “Jan al-Galb Salik,” the song that closes the album. The title translates as “I Hated You in My Heart,” the far end of the love and longing that thread through the album. It’s the oldest selection here, coming from about 100 years ago.

“My grandfather and my great-uncle,” he says.

That would be Daoud and Saleh Al-Kuwaiti, the latter of which wrote the song. The brothers, whose father came from Persian Jewish heritage, were born in the Jewish community of Kuwait in 1910 and 1908, respectively. As young men, they played crucial roles in the 20th century evolution of the folk-classical style known as sawt, before moving to Iraq, where they pioneered developments in that nation’s core genre, maqam.

Their influence and renown went from the streets to the royal palaces, via their own performances and recordings and interpretations of their songs by some of the most famous singers of the Arab world, Jewish and otherwise, including Egyptian superstar Umm Kulthum. After the creation of Israel, they moved to Tel Aviv, becoming national heroes there as well. There’s even a street in the city named for them.

Tassa was named for his grandfather, who died in late 1976, three months before Tassa was born. But he grew up only vaguely aware of his ancestors’ legacy. That was typical of the culture at the time.

“You need to understand that a lot of the second-generation Jews that came from Arab places, they were just trying to be Israelis,” he says. “So they just put it aside. They didn’t really want to explore that language or to hear that music. So I knew that my grandfather and my great uncle were singers. But in my 30s I was starting to explore it and to listen to it.”

The exploration turned to passion, and while he continued his own rock and pop career he started a side project band he named the Kuwaitis in honor of Daoud and Saleh, dedicated to interpreting their music, sometimes fairly straight and sometimes radically reworked. This proved successful in its own right, breaking ground for Arabic-language music on Israeli radio. The band even opened on some Radiohead dates in the U.S. in 2017, and the three albums they have released, starting with their 2011 debut, in some ways provided the foundation for Jarak Qaribak, though the new album’s character is all its own.

When Tassa first proposed the project, Greenwood brought in drum machines, talking about Kraftwerk as a template for their collaboration. But soon that element became a subtly integrated element. Meanwhile, Greenwood had to adjust his guitar playing to the nature of the music, in which instruments generally stick to the melody without harmonies, all in distinctive scales and modes, often involving microtones that can be challenging for guitarists. But Greenwood brought both fine instincts and restraint, enhancing the music and never imposing or intruding on it — no surprise to anyone who’s heard 2015’s Junun, an album he made with Israeli composer Shye Ben Tzur and performed by Greenwood in Rajasthan, India with a cross-genre Indian ensemble dubbed the Rajasthan Express.

On Jarak Qaribak, there’s a stuttering electro-beat here, a light wash of synths there, an echoed flugelhorn elsewhere. More distillations of already-existing modern popular music, touches from the Middle East going back decades, artistically applied. Yes, you can hear that Kraftwerk-ian pulse driving several songs. But it’s far from the quasi-disco wedding music or electro-clubby bombast you’d find commonly in the region. And always at the heart are traditional instruments — oud, qanun, rebab, violin, and hand percussion — that root this in the sawd and maqam of the past, the electronic elements never in conflict with that.

The key of the concept, though, is that each song is sung by an artist or artists not from the country of its origin, but by one bordering it. The album’s title says it all: Jarak Qaribak translates from Arabic, roughly, as “Your neighbor is your friend.”

“We decided in the project that every singer will sing a song from another country, from a neighbor country,” Tassa says. “It gives it a lot of fusion of voices and a lot of colors. And even to this day here in Israel, people, when they hear this Arabic music, they are songs that maybe their parents and grandparents listened to when they came from their countries. It brings a lot of romance, a lot of longing.”

Syrian artist Lynn A. sings the Jordan-originated “Ya ’Anid Ya Yaba” (“My Hard Headed Friend”), while Egypt’s “Leylet Hub” (“A Night of Love”) is sung by Morocco’s Mohssine Salaheddine and Egyptian singer Ahmed Doma takes the lead on Algerian classic “Djit Nishrab” (“Take a Hike”). The Israeli song “Ahibak” (“Love You”) is sung by Safae Essafi, who comes from Dubai, while Tassa himself represents Israel while singing “Lhla Yzid Ikhtar” (“So It Doesn’t Get Any Worse”) from Morocco. And the song written by his great uncle, the oldest on the album, is sung by Tunisian artists Noaaman Chaari and Zaineb Elouati.

This is not meant as a political statement, Tassa stresses. It is just a reflection of his own life and heritage — not only is there the Kuwait/Iran/Iraq upbringing of his grandfather and great-uncle, but his father comes from Yemen — and of the mixed cultures and music of the Mizrahi who have come together in Israel in recent generations. Greenwood shares that too, by marriage, as his wife’s family came from Iraq and Egypt.

“Our place here in the Middle East is very small and crowded,” Tassa says. “Even when we explore music, we are not sure where each song comes from. Is it Egypt? Is it Jordan? There are a lot of singers from all over the Middle East that are singing a lot of songs. They didn’t come from the same country. It’s like a small neighborhood.”