Peter Case is completely at ease as he plays an intimate show at McCabe’s Guitar Shop’s guitar-lined back room in Santa Monica. In Peter Case: A Million Miles Away, the recently released documentary, Ben Harper refers to this cozy space as 69-year-old Case’s “living room.” That is certainly what it feels like as Case is clearly comfortable, peppering his set with natural, witty banter that has his audience in stitches.

A Million Miles Away is named after Case’s mainstream hit with his band The Plimsouls. They performed the song during a key scene in the 1983 film Valley Girl where Nicholas Cage first kisses the titular character. For those who haven’t been following Case’s 50-year career from busking street musician to punk nonconformist in The Nerves to ripping rocker in The Plimsouls to his prolific solo career as the creator of the Americana genre (which earned him two Grammy nominations for Best Traditional Folk Album), A Million Miles Away unpacks all of that. The film dissects Case’s professional and personal life with talking-heads-style input from a cross-section of admiring musicians including Mitchell Froom, Steve Earle, ex-wife Victoria Williams, current wife journalist Denise Sullivan, musicologist Gary Calamar, and Case himself.

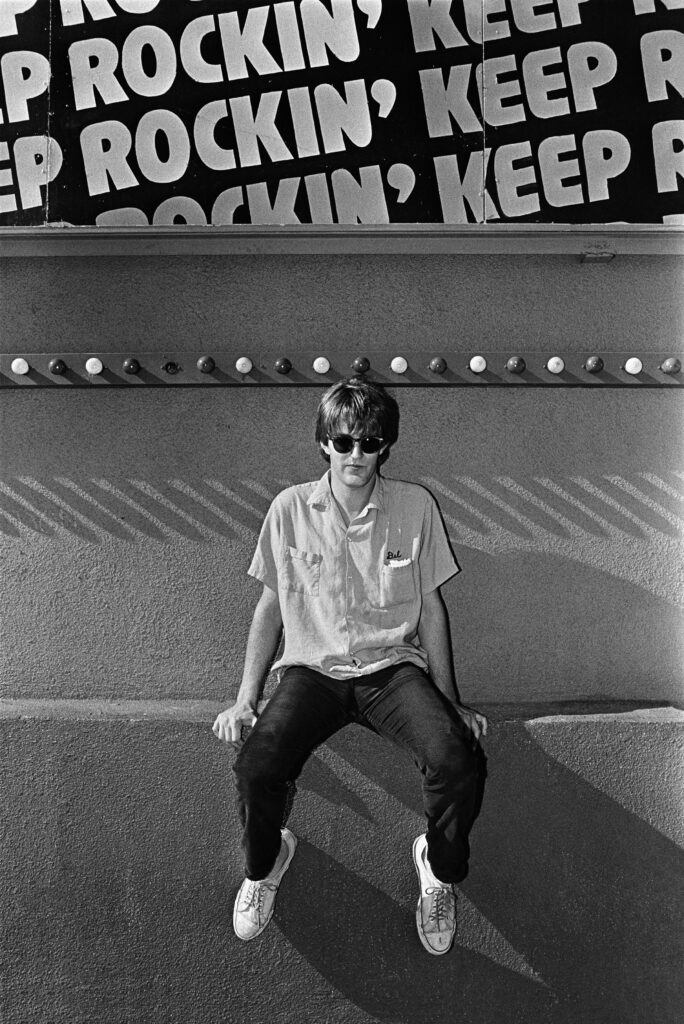

A Million Miles Away has a wealth of images, but moreso, it has amazing archival footage going all the way back to when Case was a dreamy, long-haired young man with an acoustic guitar slung across him, the body of the instrument hanging off his back. The talent matches the visual. Once Case begins performing, you would follow him anywhere. Much of the early video on A Million Miles Away is extracted from the 1973 documentary Night Shift about street musicians, in which Chase was a main figure. He was also in the spotlight in the 2011 documentary Troubadour Blues. A Million Miles Away is the first time that the focus is on Case alone.

Where A Million Miles Away hits its target is in its most jarring moments when Case is faced with severe health issues in his 50s. With no insurance or means to pay for healthcare, it is Case’s fellow musicians who came to his aid in the form of a benefit concert. A Million Miles Away is, ultimately, a case study—no pun intended—of a particular class of musician. Talented, with a hit, signed to a major label, a credible musician, a respected musician, a musician’s musician, but who has to stay on the road, driving himself around the country, in order to make ends meet.

Case spoke to us from his home in Northern California.

SPIN: Was a documentary on your life (thus far) something you were thinking about doing?

Peter Case: I was on the road, driving with my friend Frank Lee Drennen and my phone rings. I talked to this guy [director] Fred Parnes for a while, hang up and tell Frank, “That was weird. That was a movie director, and he wants to make a movie.” Lots of times these things don’t pan out and I completely forgot about it. I came off the road and was playing at my “home” club in Berkeley. Fred and one of the producers Chris Seefried flew in to meet me and decided right then that they were going to make the movie and started filming that night. I wasn’t sure how I felt about it. I don’t need a movie to be made about me. I was ambivalent for a while, but I ended up really liking Fred and [producer] Jordan Krause.

The film shows you going from being independent with The Nerves to a major label to becoming an independent solo artist. Do you feel you had to go through that experience to essentially come full circle?

What I ended up realizing is, the most informed people are the people that were in punk rock at the beginning of punk rock. That was the training ground for getting real in music. The Nerves, we were really hard on each other to get the songs to be really good. Even in The Plimsouls when we had the major label deal, we were still out there putting rodeo posters up and down Sunset Boulevard, trying to dodge the police. We put on our own gigs. We hustled on all that stuff. With punk rock, it’s got to connect. Major labels, it’s pressure from the top, but punk rock is pressure from the bottom. That’s what’s so great about it. You work your way from the bottom up. The people that have had that experience are the most effective people in the music industry.

Folk music is the original punk rock. You’re completely independent. You don’t need any pedigree to do it. You just go do it and you make it happen. That’s the same as punk rock. When things on the big label weren’t working, I was like, “Let me out of here. I’m ready to go back on the street.” When you’re punk rock, you’re not waiting to live your life—not that my music was ever punk rock, but the music’s got to be great.

‘Folk music is the original punk rock.’

You mention in the film that you regret not building on the relationships you had with people that believed in your talent. Why were you not able to do that?

I was out of my home when I was 15 and moved in with a bunch of freaks when I was 16. From there on I was in and out of the fire. When I got out to San Francisco, I was this guy on the street. Going out on the street corner and singing on Friday night on the corner of Broadway and Columbus by all the strip joints. It was scary. People would just come up and coldcock you for no reason. All sorts of weird stuff happens out there. Surviving out there, you end up with an attitude. I was a drunk. The reason I was a drunk was I didn’t like the way I felt a lot of the time. Stuff made me uptight. Alcohol was medicine. That whole attitude and that kind of behavior got in the way of like being able to get along with people.

Was your health scare a wake-up call for you?

I had a double bypass surgery. That was like getting hit by a train. It blew my mind and took a while to recover. I thought about things a little differently after that. I stayed on the road, but I had to take care of my health. Some of the moods I would get into, like anger, literally would blow me up. I just can’t go to that place. I think that’s part of the reason why I got sick. But it definitely changed my mind about things.

What are some highlights and low points of the film for you?

Highlights of the film are the footage from the street in 1974. That’s so special. And The Plimsouls live moments. Those are great to see. I wish there was more of those. I like the stuff they recorded in Sunset Sound with me playing solo stuff. My favorite things about the movie are when they talk to the people that have really been on the ground with me: Jack [Lee] talking about The Nerves, and Denise [Sullivan].

I don’t like to hear David Geffen signed us because he thought I looked like John Lennon or sounded like him. That irritates me. I got signed because I had a hit song on the radio. I wrote the song, I recorded it, I got it on the radio everywhere before I was signed to Geffen. My least favorite thing is, “And then he made a folk record. Why?” Come on, man. I didn’t make a folk record. I made a record with Jerry Marotta on drums who just got done doing Tears for Fears…Roger McGuinn plays electric guitar, Mike Campbell [plays] lead guitar. It was a different kind of record than The Plimsouls. It’s a falsehood that everybody easily mouths. There’s a lot of that in this society so the fact that there’s some in my movie doesn’t really surprise me.

What were you hoping the film would show viewers?

I wasn’t presumptive enough to think that it was going to show anything. I was talking to a good friend of mine saying, “I don’t know if I want to do this movie.” He said, “What do you care? Just do it. The worst thing that can happen is a lot of people are going to hear your music and get introduced to it.” He calmed me down. In retrospect, I’m glad Fred made the movie that he did. It seems to ring a bell with people. He’s the artist in this movie. I’m the subject. It wasn’t my movie. I knew that from the beginning.