This new series features films by and about our favorite artists, including those that embody the independent spirit.

Everybody has a Donna Summer story. That’s been Brooklyn Sudano’s experience. Sudano is Summer’s middle daughter and the co-director/executive producer of the HBO original documentary, Love to Love You, Donna Summer (released in February).

The hour and 47-minute film is a 360-degree portrait of Summer–who died of lung cancer at 63 in 2012–as a person and as an artist. The two sides of Summer are inextricable. Told nonlinearly, the film traces Summer’s family background, including being molested by a pastor and leaving her eldest daughter, Mimi Dohler, with her parents when her career was starting to take off. The film shows Summer’s early professional experiences in Germany and her groundbreaking time with composer/producer Giorgio Moroder (we wish there was more from these sessions). A multi-genre artist who broke ground in electronic dance music as well as rock–not to mention as a woman, and a Black one at that–Summer was nominated for 18 Grammys, winning five of them in different style categories of R&B, rock, inspirational, and dance.

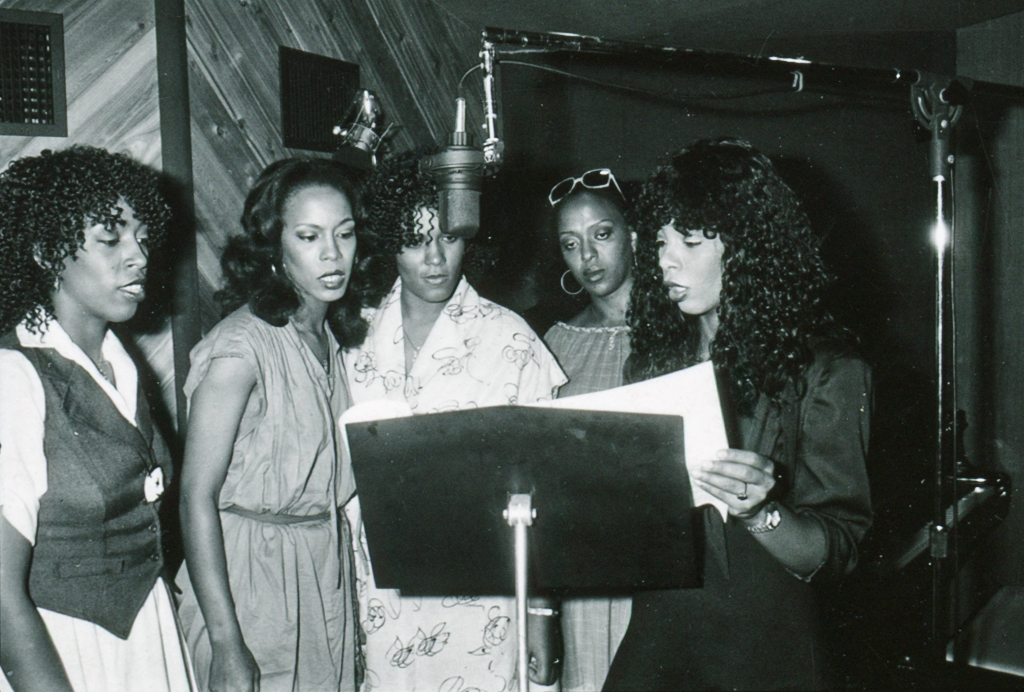

Perhaps the best part of Love to Love You, Donna Summer–besides the amazing music–is that the majority of the film is narrated by Summer. Plus, much of it is shot either by her or with the camera she bought in the ‘70s to document her life. There is extensive candid footage of Summer, the most priceless of which is arguably her at home, her face bare, with her daughters, singing, “She Works Hard for the Money” a cappella. The other voices in the film are off camera. They include Moroder, Elton John, Summer’s husband Bruce Sudano, Mimi’s father Helmuth Sommer and, most importantly, her daughters, her sisters (who were her backup vocalists), and other family members. No topic is taboo, including Mimi’s reveals about being sexually molested, which has Sudano in tears. Sudano tackles her mother’s anti-LGBTQIA+ comment controversy head-on, letting her father, and archival news footage, shed light on the matter.

Sudano’s directorial role in Love to Love You, Donna Summer has everything to do with its authenticity. A creative like her sisters, Amanda Sudano Ramirez of Johnnyswim and jewelry maker Dohler, Sudano takes a break from her acting schedule to talk to SPIN about the healing effects of making Love to Love You, Donna Summer, and how their neighbor Sofia Loren (“Auntie Sofia”) helped her mother achieve work/life balance.

What was your intention in making this film?

There were a few things. My mom passed, and a few years later, I became a mother. I was a working mom. I did my first film when my daughter was six months old. Going through that metamorphosis and not having my own mother there to ask questions, it brought up a lot of things. And then it was fans, people telling me stories, how her music or performance or an interaction that they had with her was a part of their personal histories—without them really knowing that much about her. I felt like it was time for there to be a real representation of who she was, as we, the people closest to her knew her.

How did you come to be the co-director?

That happened as I started reaching out to people. Everybody would say, “I’ve never told anybody this, but I feel like I can tell you.” In the process of doing the research and having these conversations, I realized that having me be a part of the project in a directorial way was going to be impactful. I had no experience doing it before, but I really enjoyed that role.

How did you come to pick [Academy Award winner] Roger Ross William to co-direct the film?

I saw his film Life Animated and I thought, “This guy knows how to tell an emotionally impactful story about family.” That was the kind of film that I wanted to make. It stuck with me. We had a conversation where I said, “I know what people are going to assume by me being a part of this, but I want to tell the truth.” If I’m not going to be as transparent as I can possibly be, there’s no other reason to do this. In order to really tell my mom’s story, from beginning to end, and for it to have the impact that I would like it to have, you have to tell the truth, that’s where everybody’s humanity lies. That’s where you understand their gifts and why she was uniquely positioned to be who she became. That was really important to me. I was very grateful that Roger was willing to take the journey with me.

The film is not linear in its storytelling, which is an interesting, and effective decision. How did you come to that?

Finding the structure that was going to serve this story in the best way was one of the biggest things. When you have somebody whose life has a lot of elements to it, it can feel like a Wikipedia page. It had to be able to move around. We can’t be a slave to, “This song came out in 1978, and then this song came out.” Roger and I felt strongly about using the music as an asset and a tool to the storytelling, but we felt we could make it work better in a nonlinear fashion. We thought following the emotional threads of the storytelling were more important. It took some time to fine tune and nuance, and make sure there was still enough clarity that people could understand the cause and effect of what was happening.

You also didn’t use the talking-heads documentary style, but you interviewed a lot of people who didn’t make it into the film. Why did you make that choice?

We spoke to a whole plethora of people, from Barry Manilow to Kelly Rowland, David Foster, her songwriting friends Bruce Roberts and Paul Jabara. It became a little crowded.

In terms of the music, we thought that the performances could stand on their own. When you went to one of her shows, you were in a whole world that she was creating. We wanted you to feel like you were right there in whatever moment was happening, whether it was emotionally or in the middle of a performance and the height of [her] fame. To cut to somebody in real time today would be too jarring and take people out of it.

The strength of the story was in [the interviews] by those closest to her and her family…allowing the audience to feel like they could take a peek in and feel the intimacy of that in a way that didn’t feel [voyeuristic].

The footage of her at home with your family really puts a different perspective on her as a person.

She lived that in a very real way. She had a really great relationship with Sofia Loren who was one of our neighbors. Auntie Sofia was instrumental in helping her find that footing and balance. She was a beautiful, larger than life human being, but at the same time, whenever we’d go to her house, she’d be fabulous, but she’d be in the garden and saying, “What are we making for dinner?” My mom was able to learn a lot from her at that time. She was a real mother and very nurturing and she was able to have some mentors in the process.

So much of the documentary is narrated by her, it feels like she’s making the film herself. How amazing was it to find the wealth of footage she captured herself?

She was a very early adopter of technology, which also speaks to her as an artist. She was not singular in her creativity and her artistry, whether it was the painting and the artwork or the sketches or the songwriting, or doing these little skits. Everything was about a mode of creation or storytelling. The fact that she had this camera and was doing that in the ‘70s was groundbreaking. When we found this footage—some of it I wasn’t even aware that we had—Roger was like, “This is gold.” You can see performances on YouTube, but you get a real sense of the essence of a person in those unguarded moments when they are with the people closest to them. We realized one of our biggest assets was that my mom was the cinematographer. She was the one telling her own story.

Was it difficult for you to go through the footage and talk about your mom for the years it took to make this film, and possibly after?

That’s part of the reason why this film wasn’t made earlier. Me, my sisters, my dad, my aunts, we didn’t do a lot of interviews or public statements after my mom passed. She was very private. We stuck together and allowed ourselves to work through that process as best as we could. I can’t escape my mother. My mother is always there. If I go to the grocery store, her song comes on, or somebody finds out who I am, and they have a story about her. We aren’t allowed to have a disconnect. In some ways, it’s a blessing. Her life had so much impact.

But we had to take that time and get to a place where we all felt ready to be able to speak about it and have real conversations and look at the footage and the photos. Some days it was a lot of emotions and there were tears and I would say to my editors and to Roger, “Guys, I’m okay with my tears. Please don’t feel weird about it. I’m okay with it.” I naïvely thought, “It’s been a few years. I’m good. I’ll be objective.” I had a lot of peace with my mom’s passing. But there were times where I would get a cut and I would say, “I can’t watch it tonight. I’ll have to watch it tomorrow, because if I watch it tonight, I won’t sleep.” I would have to be disciplined and know when to take a little bit of a break.

When you do something like this, and you peel back all these layers, you see things about yourself, and you understand different things about your childhood. What you thought was one thing is actually another. Those discoveries that happened in the film were real. Every time I would get new information, I would have to go back through my whole life history and recalibrate. It took a lot of work, but I’m very grateful that I stuck to it. I’m changed for this process. To be able to have done this film has been a blessing to me. It’s been healing in ways that I didn’t even expect.