Every other Sunday throughout 1993, the Mechanicsburg Denny’s, Pennsylvania’s busiest, reserved their largest, cleanest horseshoe booth for a roundtable of deeply concerned suburban mothers meeting over bottomless coffee to compare surveillance notes for any evidence of smoking, dirty magazines, or—Mother Mary, help us!—rap music found among their tween boys.

Within this ad hoc war council of six matriarchs spanning two public schools and two private, faith-based academies were the moms of my best friends Dave, Ben, and Paul. Their moms were prim, proud, and especially protrusive founders of the group; not one of them missed a single Denny’s caucus that year, and boy, did they ever make sure we knew it.

(We sure did. And we kept the nudies in a hole under some leaves in the park, alongside a few soggy cigar nubs. That rap music, though? That foul moral poison? That was inside our heads at all times, and our heads were hidden in their homes.)

When the Sunday sunset adjourned each caucus, my friends’ moms would beeline home, motherhood aflame, and poke around their boys’ rooms: “So where do you and your friends get your rap from? We know you have it. Do you have that Side-press Hills marijuana rap that made poor Danny Phelps have a fit at the dance?”

(We didn’t have Cypress Hill’s Black Sunday album yet, but wanted it bad and would have it soon. Goatee Gary, the community college guy at our mall’s Camelot Music who sold behind-the-counter-Parental-Advisory records to kids at double the price, had the week off. More about poor Danny Phelps later.)

This was all Tipper Gore’s fault. For eight stolid years her Parents Music Resource Center witch hunt had demanded—well, really, just nagged—that their black-and-white scarlet letter, the epochal “Explicit Content” sticker, be branded upon any album fitting their ambiguous definition of “dangerous.” History may not repeat itself, but it often rhymes, and this was the 1950s rock and roll cock-block all over again.

Tipper’s book Raising PG Kids in an X-Rated Society once drove the frenzied moms to picket the mall food court the day Dr. Dre’s The Chronic came out, earning them two paragraphs and a photo in our local paper, The Patriot News. The reporter had asked for, but their group didn’t have, a name. Imagination was never their strong suit. At our lyrically minded school lunch table, however, we called them the PCC—Parental Crackdown Coalition.

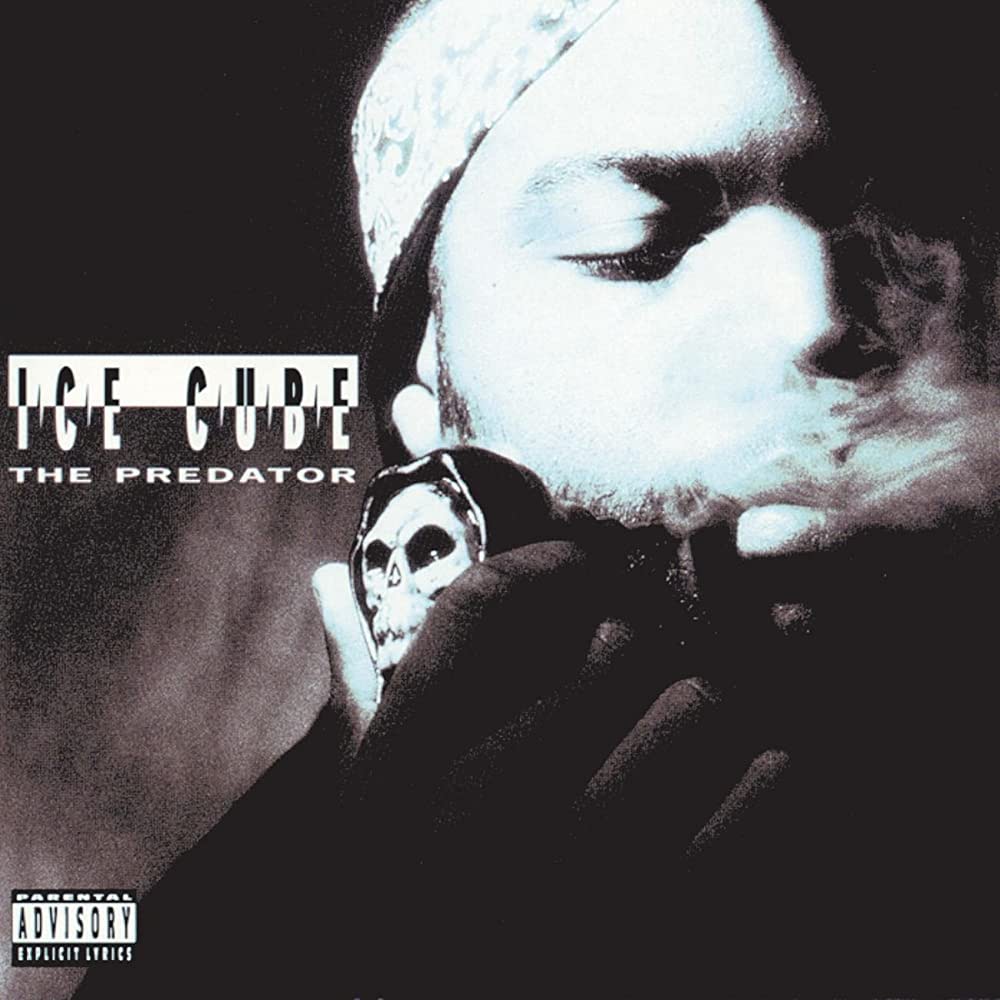

Their newsprint cameo upped the ante; the shakedowns intensified. Dave’s mom discovered Ice Cube’s The Predator CD under his mattress, said a fervent prayer, and shattered it with a hammer—doing it in front of him for extra impact. She called Paul’s mom, who that night searched Paul’s bedroom while he slept, found an Onyx tape wrapped in Fruit of the Loom briefs in his sock drawer, screamed like Janet Leigh in Psycho, and shook him awake by the shoulders.

Ben’s mom got the harrowing news the next morning and ran Ben’s whole room during the school day, but lucky for Dave’s Wu-Tang disc, she never thought to check the polystyrene pop-up ceiling tiles in their basement bathroom. My mom, on the other hand, a voluntary outlier from these curmudgeons, simply asked over meatloaf and mashed potatoes one night what I liked to listen to. I said “Rico Suave.”

“All you see is big black boots steppin’

Use my steel toe as a weapon

Kick ya and flip ya, now they want to

Label this tape with the sticker”

– Ice Cube, “Wicked”

The PCC was hell-bent on saving us, but it was too late. The brash Vesuvian sounds of golden-era rap had us by the brain stem. And, yes, sounds.

Granted, the tales of sex, drugs, and violent, forbidden lifestyles in dangerous urban communities might have been a subliminal draw for Caucasian kids in a milquetoast town with 10 Black students in a junior high of 800…but make no mistake: What truly fascinated us was the psycho-sonic mayhem.

Classic rock, xerox pop, and hair metal soundtracked our single-digit years in the early ‘90s. And sure, we knew “Ice Ice Baby” and “U Can’t Touch This” inside out, but they weren’t rap songs, just Queen and Rick James ripoffs featuring dancing, smiling guys in genie pants (Vanilla Ice and MC Hammer).

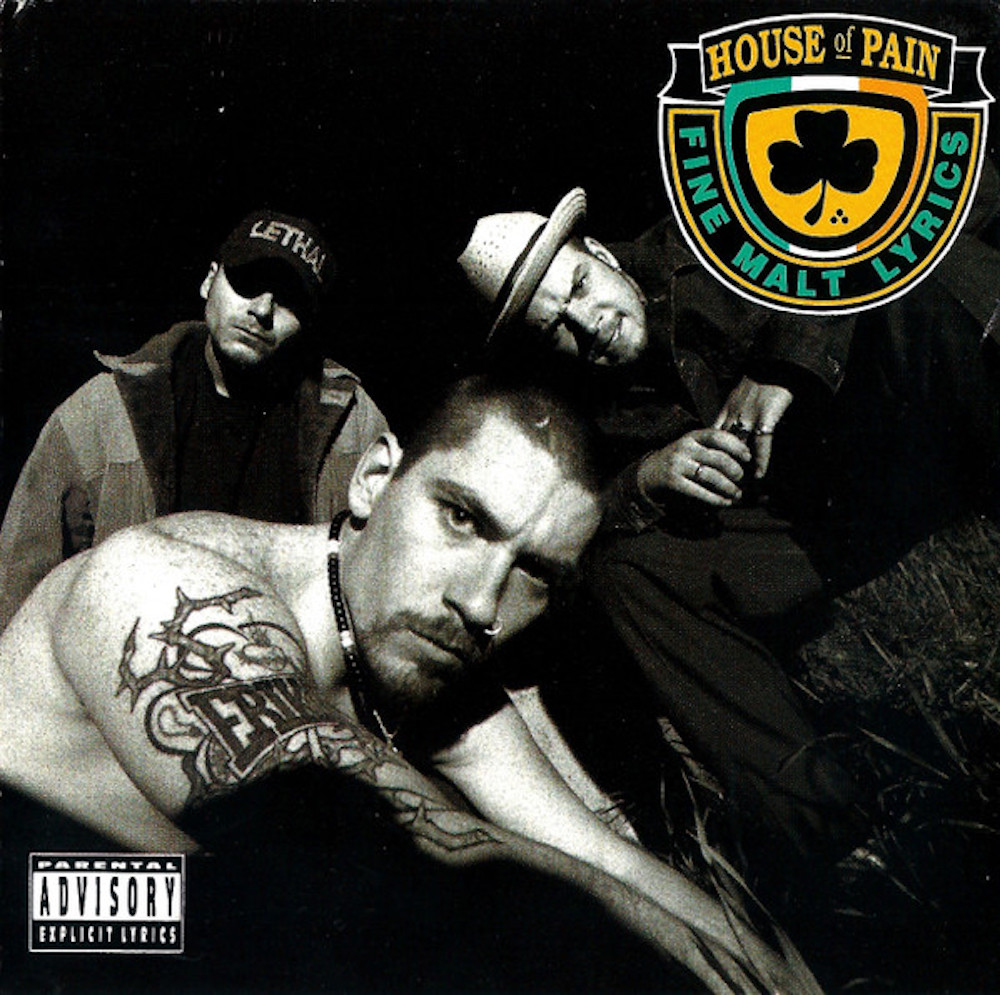

On the other hand, Cypress Hill’s “Insane in the Brain,” Ice Cube’s “Wicked,” House of Pain’s “Jump Around”? These were not the sounds of mere mortals in a room playing instruments together. These were the sounds of massive castle doors creaking, undead eagles screaming, ghosts having orgies, and demonic car alarms.

And the drums! Kicks with the impact of semi-trucks backfiring, hi-hats like grandma’s favorite china being smashed. Sub-bass so dark and deep it triggered bathroom visits. Potent, perplexing, elephantine sounds, off-kilter noises in synchronized dysfunction, captured from the nether and woven into dense, mesmeric spells.

What’s more, to 12-year-olds with no concept of sampling, the mere existence of rap beats was an utter mystery. Where in the hell did these things even come from? Were they alien radio signals? We couldn’t grasp what was happening. The idea of a musical Frankenstein was beyond us, and so, together, confused and aroused, we worshiped rap beats like early hominids did fire.

“I won’t ever slack up; punk, ya better back up

Try and play the role and yo, the whole crew’ll act up

Get up, stand up, c’mon, throw your hands up

If ya got the feelin’, jump up towards the ceiling”

– House of Pain, “Jump Around”

All that summer, my friends and I gathered at Dave’s to blast our newest finds on his parents’ pricey hi-fi system before they got home from work. When the pristine audio quality brought certain beats to life, a certain spirit of highly enjoyable mass panic would descend upon us, and almost involuntarily, we would chant and bounce in place until completely spent.

We called these ceremonies “jump-offs.”

Strategic sleepovers began to take place at Paul’s on Saturdays, the night Ed Lover hosted Yo! MTV Raps. Once Paul’s dad finished slamming Busch Lights and yelling at SportsCenter, we waited for the stairs to creak and snoring to start, then crept down into the den, tuned to channel 42, and held a cassette recorder against the TV to capture new jams before they hit the mall.

Surrounding the TV set with sofa cushions helped block the ambient snores, but our recordings were still near-silent and brittle as Ritz crackers. Somehow that made them all the more exciting to listen to. The urge to jump off on those nights was overpowering, nearly impossible to resist. Rap was triggering something primal within us.

The need was growing. Restricting our listening to safe weekday sessions at Dave’s wasn’t scratching the itch. We began to hold surreptitious Saturday jump-offs in Paul’s living room while his parents were upstairs, and upon hearing rapid footsteps (and “Paul? Paul! PAUL!”), we’d pull the disc, grab our bikes, and pedal off to the park.

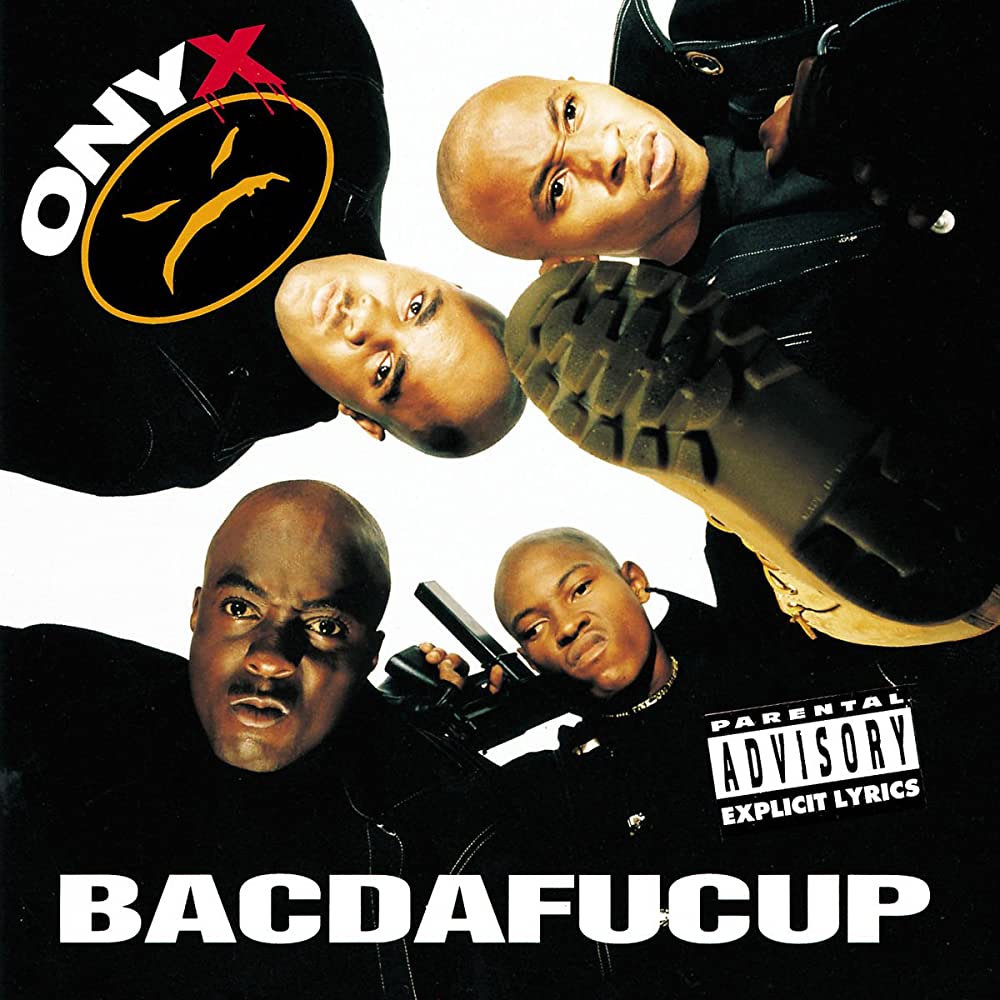

We had our favorites. Onyx’s “Slam” and House of Pain’s “Jump Around” were powder kegs, but by fall we wanted something harder…riskier. Goatee Gary at Camelot knew exactly what we needed (for $26 on cassette): Cypress Hill’s “Insane in the Brain,” a crazy, hazy, manic apparition of a song, which come that October, come our junior high Halloween social, would spark a teenage riot still spoken of in hushed tones by retired Mechanicsburg area school board members.

“Slam, da duh-duh, da duh-duh

Let the boys be boys

Slam, da duh-duh, da duh-duh

Make noise, b-boys”

– Onyx, “Slam”

That brisk and fateful Friday, our socials’ usual DJ, the WASP-y eighth grade biology teacher who famously used golden tools when leading class frog dissections, was skiing in Stowe. In his place stood an older, overweight Latino man wearing a red hoodie airbrushed with the name he kept yelling in between songs, Manny Movez.

All night, Manny spun sure-shots—Snap!’s “Rhythm is a Dancer,” TLC’s “What About Your Friends,” “Tennessee” by Arrested Development, every dance-demanding C&C Music Factory jam—while behind the DJ podium he did the robot, the running man, and even moonwalked in place—and all night, maybe 20 young backs left the gymnasium wall.

Desperate to rouse a crowd, Manny rolled the dice. He cued “Insane in the Brain”… “Who you tryin’ to get crazy with, ese?” …and something snapped.

All social tension lifted, and that same delicious sense of panic Paul, Dave, Ben, and I knew so well descended upon the gym. Like kernels becoming popcorn, one after another—jocks, geeks, hotties, goths, and townies, then even the special-needs students—over 100 kids suddenly forgot what cool meant and hit the dance floor, jumping themselves into one dissociated mass of sweaty adolescence.

It wasn’t a mosh, there was no pushing. It wasn’t skanking, there were no skank arms. It wasn’t pogoing, which Debbie Harry says involves “arching your back and throwing your head around.” It was simply, definitively, a jump-off: arms prone, hands against the thighs, drifting slightly while airborne, brushing shoulders and backs without any real collision. It was truly communal, an act of unconscious cooperation, and the most powerfully accepted by all peers a junior high kid could possibly feel.

As “Insane in the Brain” ended and our mystery buzz evanesced, a beaming Manny Movez crossfaded into “Achy Breaky Heart,” absolutely murdering the vibe. Suddenly back to feeling nude and vulnerable, kids ran for the walls like roaches with the lights switched on, though one particularly worked-up honor student named Danny Phelps continued to jump and chant the Cypress.

“Insane in the membraaaane! Crazy insane, got no brain!”, over and over. Grabbing a folding chair from the snack table, Danny placed it in the basketball free throw lane, carefully removed then hurled his glasses straight up, and in a baffling attempt to grab the rim of a 10-foot hoop, backed up, ran full speed and jumped on it. “Insane in the membraaaa—”

When the folding chair folded (as folding chairs are prone to), both Danny’s feet were trapped, and SPLAT! His momentum catapulted him to the hardwood floor face first. The head-on-pine thwack was audible above the Billy Ray, and several adult chaperones screamed. Manny’s grin fell limp, and as he abandoned the lasso dance he saved for the “Achy Breaky…” chorus and scrambled for the pause button, Danny began to bleed and shake.

The paramedics soon arrived, and in order to address the collarbone peeking through Danny’s skin, cut the poor guy’s Brooks Brothers Oxford off of him in front of the entire gawking, whispering dance. After shielding the puncture with gauze, they slid a wooden plank beneath him, strapped him to it, applied a foam neck brace, and carried him out delirious, screaming in more than pain. I remember wondering if he knew the song was over.

Our Halloween social ended an hour early that year. Ben’s mom heard the ambulance dispatch on her police scanner and showed up in the parking lot wearing pink and purple curlers. We never saw Manny Movez again. That Saturday’s rec-league soccer games were lined with stone-faced parents playing a morbid adult game of telephone, and on Sunday, Denny’s was forced to add an extender table and two coffee carafes to the PCC’s horseshoe booth.

POST-SOCIAL FINDINGS

So am I saying it was the Cypress? Let’s be real: B-Real of the Hill didn’t drive Danny batshit. Danny was plenty sick of nerd-dom, got caught up in the fellowship, and tried something very stupid to earn respect—being able to touch a basketball rim was the pinnacle of Jordan-era junior high cool.

The real question is, how did “Insane in the Brain” instantly dissolve a gym-full of pre-adolescent self-doubt? What did it have that “Gonna Make You Sweat” didn’t?

What creative sorcery lurks within “Insane in the Brain” and other Cypress songs like “I Ain’t Goin’ Out Like That”?

What is it about House of Pain’s “Jump Around,” Onyx’s “Slam,” and both Ice Cube’s “Wicked” and “We Had to Tear This Mothafucka Up,” that 30 years later still frenzies crowds instantly?

After innumerable erudite analyses, I now postulate the existence of a sacred equation within these songs, a funky-fly Fibonnaci sequence of common structures, tempos, sounds, keys, and music video imagery; a psychoneurological catalyst that, irrespective of audiometric capacity, is completely capable of triggering compulsive jumping among rap fans of any age.

CASE STUDY: THE ART OF THE JUMP-OFF

I. THE NATURE OF THE BEATS

SHORT AND SIMPLE

All of our jump-off songs consist of four or five tightly-looped samples, with intros that function as warnings—a single phrase or sound repeated once or twice before the beat drops provides just enough time for the listener to recognize what’s coming, but not enough time to resist the impending ruckus.

More than half contain a single-bar upright bass loop over a two-bar drum loop, and each feature either a chant-along title chorus, or one scratched word repeated ad infinitum—no long instrumental performances, no expanding orchestral arrangements, only simple sound blocks for great minimalist music.

The compact build provides relentless punch, giving the beats a hypnotic quality that provides the perfect platform for rapped verses to stand atop and command attention. The spare styling of our jump-offs however had as much to do with legal and technological reasons as artistic ones.

Many early rap beats contained entire segments of other artists’ songs, an approach that drew lawsuits once rap became bankable. In 1991, a precedent was set when De La Soul was hit with a $1.7 million payout to ’60s folksters The Turtles for swiping a healthy portion of their “You Showed Me,” Harsh for sure, but a similar lawsuit filed against Biz Markie, one involving possible jail time, was about to change the hip-hop sampling game forever.

TIGHT AND GRIMY

For using both the music and lyrics of Gilbert O’Sullivan’s 1972 hit “Alone Again (Naturally)” to record his own song of the same name, a judge fined the Biz a quarter-million dollars, pulled his single and album off the shelves, and, declaring that audio larceny was actual theft (as opposed to theft of intellectual property), arraigned him on criminal charges.

Biz, possibly the rapper least suited for jail in the history of jail, fought the law for two years and went bankrupt in the process. The dangers of careless sampling had been demonstrated clearly enough that nearly the entire industry shifted production techniques, and took to building beats using obscure, filtered, and rearranged song chunks in order to avoid lawsuits.

This new approach coincided with the rise of the E-mu SP-1200, a portable sampling workstation capable of doing what previously required a studio’s worth of gear. The convenience did come with caveats, however. The SP processed audio at a 26 kHz & 12-bit resolution rate (as compared to studio-standard 48 kHz & 24-bit), leaving the sound coming out with noticeably less clarity than the sound sampled in. And offering a mere 2.5 seconds per sample pad, producers accustomed to using entire song slabs found themselves handcuffed.

As an end-around to longer sample times, production hacks were developed, the most popular of which degraded the SP sound quality even further. Sounds were sampled in at a high speed, then digitally reduced in pitch, expanding the original audio into a longer usable form, but imparting a grainy, digital-crunch in the process. Though technically a lower-quality audio, this characteristic voicing came to be a treasured element of SP-produced beats.

The SP also featured a trademark “swing” function used to humanize its sequenced drums by imparting minor inaccuracies in their programming patterns. The swing control essentially “gave the drummer a drink,” producing a now-unmistakable percussion touch beloved by ‘90s rap fans. All of our case study jump-off beats were produced using the Emu SP-1200, and with an analytic ear, its distinct traits can be both heard and felt.

II. TEMPO NEAR THE HEART’S EXERTION RATE

I say “felt” above, as our second criteria involves a jump-off’s direct interaction with the human body, namely its cardiovascular circuitry. The Mayo Clinic identifies 60-100 beats-per-minute as the “resting heart rate,” beyond which our bodies enter into a state of exertion and release chemicals that mask pain, increase sensations of pleasure, and at length, lead to what’s known as a “runner’s high.” Coincidentally, the tempos of all six jump-off songs examined hover between 100 and 107 BPM (averaging to 102 BPM).

This isn’t to suggest any song over 100 BPM pumps us full of happy chemicals—if heart rates simply synced to music tempos, festival bros’ chests would explode during EDM songs. However, our brain wave and breathing patterns do sync to the rhythm of the music we hear, and our heart does follow these biorhythms. Uptempo music does raise the heart rate, and if both rhythm and tempo shifts occur as the brain’s auditory cortex encounters a BPM rate it associates with borderline endorphin release (the low 100s), a pleasant state of alertness can occur.

This alignment of biorhythms is the result of a phenomenon called entrainment, which Cambridge Dictionary defines as “the process of making something part of a flow and carrying it along.” Amazingly, entrainment occurs externally as well, including between hundreds (or thousands) of live music fans. Seeing that each listener’s brain waves sync to the rhythm of the music they hear, and all are listening to the same music, an entire audience’s brain waves can naturally synchronize—along with those of the performers!

In such proximity, group mental entrainment translates to the collective physical, which is why it always feels easier to dance when those around us are dancing. The shared biorhythmic groove compels us to move; it’s the silent cause of the near-involuntary foot-tap or head-nod (and at our Halloween social, a large factor in the raucous jumping) that occurs when listening to music in a crowd.

And now, with the historical precedents and medical minutiae of our study firmly established….on to the fun shit!

III. REPETITIVE, UNSETTLING SIREN SOUNDS

There’s no other way to put it: All six of our beats have some seriously weird-ass noises in them. Sounds that are prone to straight-up bug a person out when heard again and again and again. And again.

Some Redditors swear “Insane in the Brain”‘s primary strange sound—the one resembling the jiggling, battery-operated, hanging rubber bats Walmart sells at Halloween—is really a sped-up recording of bagpipes, while others claim it’s the horse “neigh” sound from Mel & Tim’s “Good Guys Only Win in the Movies.”

Whether one or neither, it plays over 70 times in the song, every three seconds, which is pretty loco.

“Jump Around” has that famous horse-in-an-electric-chair sound, which legend has it is either Prince’s scream from the 1991 track “Gett Off” or the sax opening on “Shoot Your Shot” by Junior Walker & the All Stars. It too repeats 70-plus times in three and a half minutes (again, every three seconds)—many more than enough repetitions to sear a hole in one’s good judgment. And behind it throughout, what sounds like hangry babies crying through a fried-out shortwave radio. That’s not too soothing, is it?

In “Slam,” take note of the eerie, high-pitched sound that fans haven’t identified, the one that sounds exactly like what plays when Venkman, Egon, and Spengler discover ectoplasmic ghost snot in the basement of the New York Public Library. This is no come-and-go noise like the others; it’s what producers call a “pad,” a continuous drifting sound that here lurks in the background at a high pitch, grinding your nerves without revealing itself.

Cube’s “Wicked” has a World War II blitzkrieg siren, slowed for pangs of impending doom, and a synth line from Ohio Players’ “Funky Worm,” twisted, sped-up, and lo-fi’d into vibes of creeping manic psychosis—the latter one literally doesn’t stop for four minutes straight.

It can also be fairly said that “We Had to Tear This…,” with its tiny machine-gun, bee-buzz fart noise and pixelated lady-screams, does very little to brighten the human condition.

IV. THE PERFECT KEY

Irrespective of genre, a song’s key has a way of intrinsically conveying familiar emotions. A minor key naturally projects sadness or longing, while a major key emits positivity and upbeat feelings.

Written in 1806 by Christian Schubart, a contemporary of Mozart and Beethoven, the book Ideen zu einer Aesthetik der Tonkunst (Ideas Toward an Aesthetic of Music) is a lamplight of formal music education, containing perhaps history’s most vivid and instinctive descriptions of keys. When applied to our jump-offs, Schubart’s writings demonstrate the impeccable key choices made by our jump-offs’ producers.

“Slam”

The key of B major is one Schubart designates as “announcing wild passions…,” adding that “Anger, rage, jealousy, fury, despair, and every burden of the heart lie within its sphere.” Sounds a bit like every sound, expression, and bodily movement any member of Onyx has ever made, asleep or awake, from the moment of their conception to the instant you read this.

“Wicked”

B flat minor is a key notated as “Dressed in the garment of night, surly, very seldom of pleasant countenance. Mocking God and the world; discontented with itself and with everything.” Consider, the song’s entire music video and album artwork are both nearly pitch black, and wicked is the Bible’s most common descriptor of Satan.

And surly? C’mon, that’s been Cube’s resting face for the past 40 years.

“Jump Around”

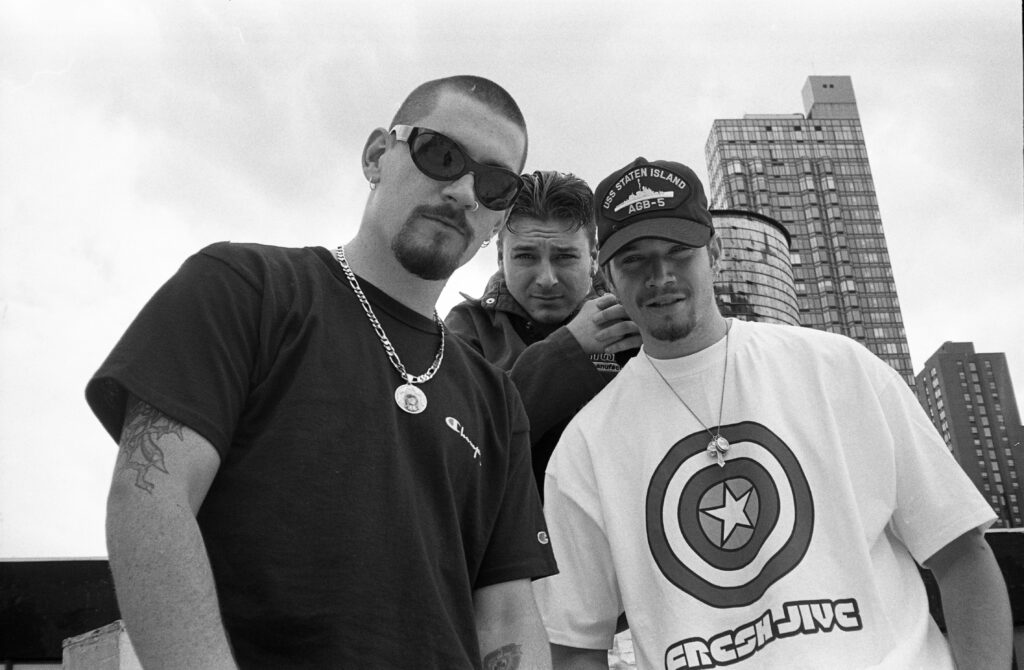

“Jump Around” is in E major, a tonic space Schubart says embodies “Noisy shouts of joy and laughing…incomplete pleasure, bickering, short-fused and ready to fight,” a description befitting a music video full of loud, drunken young Irishmen spilling beer, annoying, slapping, and shoving one another at New York’s 1991 St. Patrick’s Day parade.

“We Had to Tear This…”

Schubart says F# major speaks to “Triumph over difficulty, a free sigh of relief uttered when hurdles are surmounted; the echo of a soul which has fiercely struggled and finally conquered.” Being that this song is a celebratory narrative of the ’92 L.A. Riots that followed the Rodney King beating…well, there you have it. Herr Schubert for the win.

V. MUSIC VIDEO MAYHEM

Aside from Richard Simmons’ career-pinnacle mail order tapes, no visuals recorded in the early ‘90s seem to catalyze the calves and trigger the toes like textbook jump-off music videos. Let’s examine a whopping seven shared characteristics from some of the most mesmerizing rap clips to ever scald MTV, BET, and, on rare occasion, VH1.

Tireless Jumping Crowds

Pretty simple, this one: The music videos for five of our six jump-offs incorporate large crowds jumping—straight up and down, in one place—from start to finish. Only five, because Priority Records, for some reason, chose to forgo a big-bucks video for “We Had to Tear This…”

Nonstop Destruction of Property

Predictive of the current rage room trend, the “Wicked” clip is four minutes of things exploding while Anthony Kiedis and Flea stain Bob Vila’s legacy—kicking out windows with Doc Martens on, hitting ovens with barbed-wire bats, bashing through drywall, frame studs, and trailers with a sledgehammer. And while nothing actually blows up in “Jump Around,” a few cars do get dented, bottles break, and some perfectly useful tables are thrown around.

What do you know—Onyx hate home improvement too! As their video extras smash window frames hanging on chains, Sticky Fingaz’ own long-haired, tattooed, shirtless white rockers friends from Biohazard damage innocent rooms, knock trash cans into sheet metal shacks, and bounce off one another in a junkyard exactly like the one in “Wicked.”

Human Skulls and Bones

Nothing supports jumping like the skeletal system, and the stage in “Insane in the Brain” is backed by the giant Cypress Hill skull logo, with a big ol’ mess of bones hanging on the ceiling—including some real bone-chandeliers—and what seems to be Keith Haring bone drawings for wallpaper. And the entire “I Ain’t Goin’ Out…” video? Ding! Bone-us round.

“Wicked” sees Ice Cube rocking his skull tee, carrying a skull-shaped weed device, and wearing a skull ring half the size of an actual skull. In “Slam,” Onyx’s Fredro has a skull bandana he seems to really like wearing, and the group’s logo is basically just a caveman’s drawing of the Misfits skull, with the smile flipped.

Hardware Store Weaponry

What is it about jump-offs and the Ace Hardware home and garden section? “Wicked” shows kids pick-axing cars as random pedestrians crush ice blocks with shovels, while “Slam” has multiple crowbar-swingers in a construction site containing a top-of-the-line, small-duty bulldozer.

The shady graveyard crew in “I Ain’t Goin’ Out…” wields shovels too—trench shovels, edging shovels, flat shovels, take your pick—weighted mallets, and even a few rakes for some reason, while in “Jump Around” a guy whacks a girl in the grill with a damn measuring stick. Now that’s a tool bag.

Funerals, Flames, and Tombstones

If the hip are to be made to hop, infernos and eternal rest imagery are musts. “I Ain’t Goin Out…” has pitmen carrying torches, digging graves and hauling body bags as tombstones near bonfires explode without cause, while the “Jump Around” opening has pallbearers in a chapel cemetery bearing a casket in slow motion. “Wicked” has plenty of burning dumpsters, cars, buildings, Molotov cocktails, and, towards the end, what looks like a fire that’s been set on fire.

White Strobe Lighting

Ocular disorientation can beget a proper wig-out. B-Real does rap a disclaimer for those prone to epilepsy (“Look, but don’t let your eyes strain”), but “Insane in the Brain”, “I Ain’t Goin Out…”, “Wicked,” and “Slam” all have blinding white strobe lights of varying speeds and intensities throughout the entire…damn…video.

We get the idea, guys: You’re high, we’re high, it looks pretty cool, just pull the plug before our pets have seizures.

Folks Getting Walloped and Chased

Classic jump-off vids never forgo multiple street scuffles. “Wicked” has prostitutes wailing on their pimp, asses get kicked constantly throughout Onyx’s “Slam” video, and “Jump Around” is a slugfest—parade-goers brawling, that guy in a satin coat getting whupped by police, the bleeding preppy in the cream-colored J.Crew sweater and OG Notre Dame starter jacket. To boot, “I Ain’t Goin’ Out…” and “Wicked” both feature visibly exhausted people being chased in the streets, beat-downs surely impending.

VI. DJ MUGGS, OF COURSE

While there certainly are a good number of golden-era SP-1200 rap beats featuring wise tempo and key choices, wonderfully strange sounds, some of the hands-down best—and four of the six we just reviewed—were crafted by the legendary DJ Muggs of Cypress Hill.

Furthering the maelstrom-beat style introduced in 1988 by Public Enemy’s Bomb Squad production team, Muggs and the Hill took the madness mainstream in 1991 with Ruffhouse Records, the only major label willing to invest in what the entire industry deemed an un-bankable style of music. It paid off—Cypress Hill sold millions of records, and 30-some years later they still headline festivals worldwide.

OUR MOST EXCELLENT CASE STUDY CONCLUSION

Now, before any accusations fly, let’s address it: By writing a feature that distills to a DJ Muggs production equation, am I calling the man unimaginative? To the contrary! True artistic mastery lies in establishing a trademark technique and practicing it at length without the results ever feeling cliché or dated.

Consider Scorcese gangster flicks, the same actors jawing put-on accents, the AM jukebox soundtracks, fatiguing runtimes, and that same walkabout-voiceover shot. Take Zeppelin’s entire catalog of sex-moan vocals with occult-lite subtexts, onanist double-neck solos, stubborn rhythms, and chest-less outfits.

Even Bob Ross oil-painted nature only, his entire career—on the same size canvas, in the same black room, rocking the same light-colored, wide-collar, poly-cotton button up and white-fro—and dammit if I won’t storm the home of whoever denies his mastery.

If anything, to this day, the power of a Muggs beat has only intensified, and if watching over 80,000 people lose their minds all at once to “Jump Around”—both at night in Belgium and in the daytime in Wisconsin—doesn’t raise a few hairs on your arm, well, you just might be on the wrong website.

EPILOGUE (YOU THOUGHT A “CONCLUSION” WAS A CONCLUSION? NOT SO FAST, BUCKY…)

It wasn’t until sophomore year when a studio tech visiting music class on career day lifted the veil on rap beats for Dave, Paul, Ben, and me—they were just musical taxidermy, sound chunks manipulated, re-arranged, and automated with a machine, not unlike the animatronic band at Chuck E. Cheese. It was a sad day of forced maturation for our crew.

Junior year marked the surrender of the PCC. The creeping ivy of rap had crawled over their white picket fences, across their kempt green lawns, and around their Victorian homes, weakening the old walls between cultures. Local radio began to play rap, and thanks to CD clubs like BMG and Columbia House, everyone we knew amassed rap libraries, direct-to-door, for pennies.

The Tipper technique inverted, and Parental Advisory stickers boosted sales. To get one, many artists went balls-out offensive; others had bootleg stickers made. It was unspoken, CDs without the black-and-white were totally lame — or they were edited versions, and I clearly recall several of those BMG mistakenly sent us being frisbeed out of moving car windows.

Speaking of vehicles, Dave and Paul went on to purchase enormous car stereos, with subwoofers that set off car alarms (and in Dave’s case, repeatedly shook the rearview mirror off his windshield). To fund a stereo for my ‘82 Volvo, I stayed busy mail-trading mixtapes of rare and unreleased rap via America Online user forums, amassing a ginormous collection that I mass-dubbed copies of and sold in the hallways at school.

In the decades following our fateful Halloween social, I’ve encountered a truly surprising number of stories from new friends of similar backgrounds involving rap-induced hysterias at their own early ‘90s school dances. It seems the raucous results of timid youth meeting foreign, forbidden sounds weren’t unique to our junior high gym. Just imagine all the Danny Phelps!

SUPPLEMENTAL RESEARCH

To study the first impression of jump-offs on the innocent mind, we played 30 seconds of the following songs (the edited versions, you fiends!) for a 7-year-old girl and a 5-year-old boy, then asked them to answer the following questions.

“INSANE IN THE BRAIN”

Makes Me Feel Like

Girl: I’m in a giant haunted mansion

What I Picture

Girl: Glow in the dark skeletons

“JUMP AROUND”

Makes Me Feel Like

Boy: I’m riding a jack in the box

What I Picture

Boy: Pirate ship in a battle

“WICKED”

One Word to Describe

Girl: Winter

What I Picture

Boy: Mice running and squeaking

“SLAM”

Makes Me Want to

Girl: Do karate

“Makes Me Feel Like”

Boy: I’m a crazy octopus

“I AIN’T GOIN’ OUT LIKE THAT”

What I Picture

Girl: World War II

Makes Me Want to

Girl: Run away from people