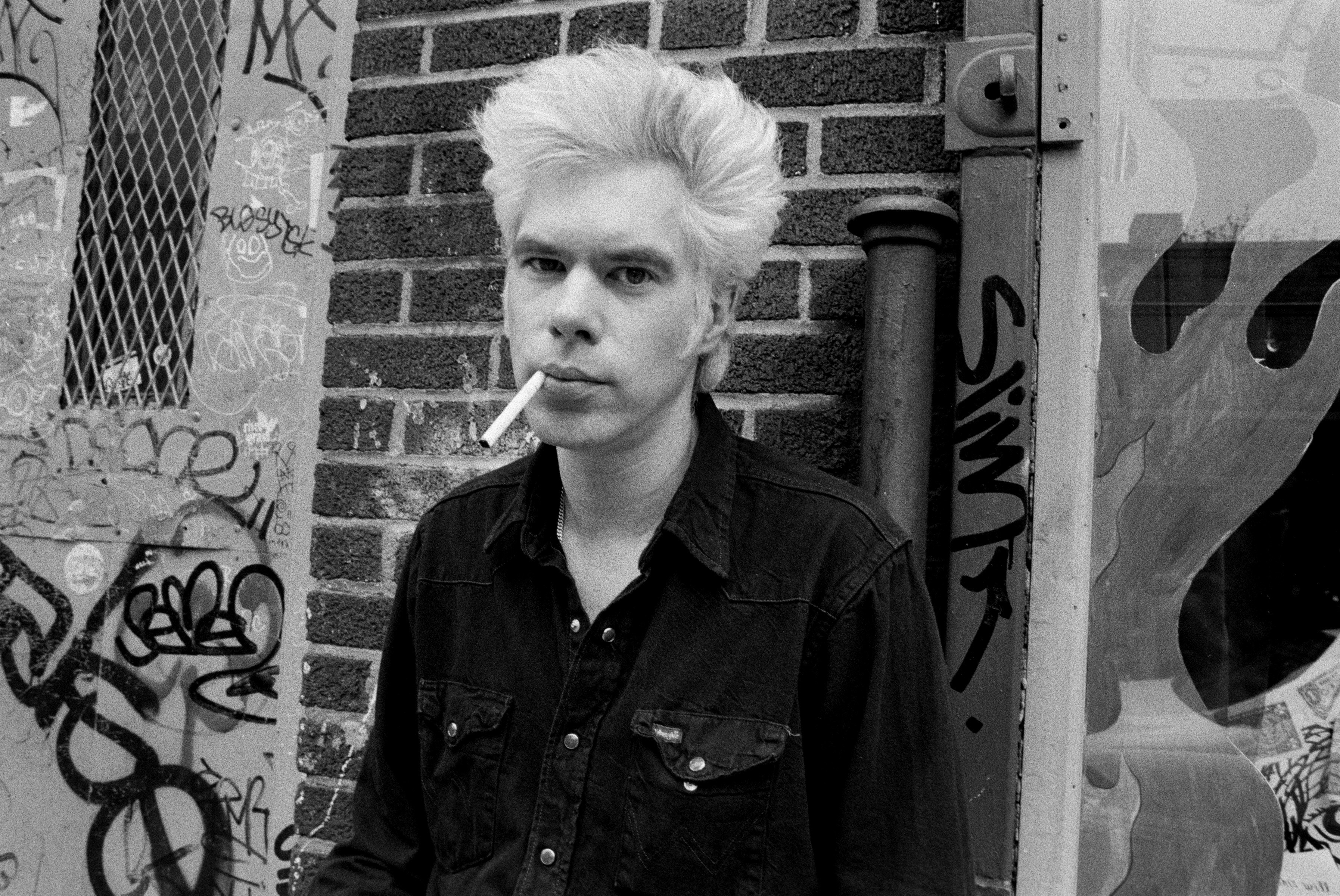

Jim Jarmusch is one of the most prolific and creative anomalies in the cinematic zeitgeist, often credited as a progenitor of the American independent cinema movement with his early masterworks Stranger Than Paradise (1984) and Down by Law (1986). Like his 1980 debut, Permanent Vacation, they exemplified Jarmusch’s unique blending of various musical styles with his visual imagery.

A deliberation on Jarmusch’s oeuvre requires consideration of how his use of music relates to narrative, a symbiotic relationship where an image’s intention is inextricable from its aural cues (or lack thereof). His filmography, especially in his earlier career, was often infiltrated by a unique array of various musical artists, like Tom Waits, Iggy Pop, RZA, John Lurie, Gary Farmer, Youki Kudoh, The White Stripes, and Screamin’ Jay Hawkins—to name a few. And then Neil Young famously scored his 1995 neo-Western, Dead Man.

Also Read

Jim Jarmusch: Our 1989 Interview

In the world of Jarmusch, music is a unifying language, which also taps into the international flavors that often define his films. A member of the early 1980s No Wave band The Del-Byzanteens (whose music was featured in Wim Wenders’ 1982 film The State of Things), music has been the driving force behind his entire career, which might heighten expectations for his band Sqürl’s new album, Silver Haze.

Sqürl originally formed in 2009 as Bad Rabbit, between Jarmusch, his longtime film associate (and producer) Carter Logan, and sound engineer Shane Stoneback, expressly to supply music for his film The Limits of Control. Changing their name to Sqürl (a reference to the Cate Blanchett segment of 2004’s Coffee and Cigarettes), they would also release EPs for his 2013 film Only Lovers Left Alive (including a moody cover of Wanda Jackson’s “Funnel of Love” with Madeline Follin of Cults).

And now, they’ve crafted their first record, collaborating with guitarist Marc Ribot (Jarmusch’s longtime associate, who worked on the soundtrack for Down by Law), the mystical British-German singer Anika, and the ethereal Charlotte Gainsbourg (who also appeared in Jarmusch’s short French Water for Saint Laurent’s spring/summer 2021 collection).

Together, Jarmusch and Logan sat down to talk about their approach, overarching themes of their new album, and the power of meaningful collaborations.

SPIN: I know Sqürl was formed in 2009 for the soundtrack of Limits of Control, and you also put out several other EPs as well as the Only Lovers Left Alive soundtrack. Was there always a plan to put out a full-length record?

Jim: Oh, boy, it’s a weird question…because we don’t follow any master plan. We really like EPs and thought at one point [that] we would just put out EPs because we do other things, and then it’s less time. We’re always gathering stuff for more. We could put out more albums probably right now because we’ve gathered a lot of stuff, but we had a good time period to work on an album. We had (producer) Randall Dunn, and he was really interested.

Carter: It was about the material that we had gathered in a particular amount of time between [making] The Dead Don’t Die. It’s the music, essentially that we made following that.

Jim: The length of things that you release [is] so arbitrary. For example, our feature films are 90 minutes to two and a half hours based on the turnaround in a movie theater. It’s not based on the aesthetic design of filmmaking, because a great film can be two minutes long or six hours long. The whole idea of these arbitrary formats are interesting and silly, too, in a way.

This is that format because it exists, and we just set stuff into that format. Personally, I love EPs. I like the amount of time you listen to a certain, I don’t know, just series of music or pieces that were made at the same time or not. I love EPs. It’s arbitrary, but it doesn’t matter the format.

“Berlin ’87” was the first track release, and you had a music video directed by Jem Cohen, which is really moody and beautiful. And eerie.

Jim: I lived [in Berlin] in 1987, and while I was just laying down those tracks, I was in an abstract way thinking about my memories of those times, which were bleak and also interesting. There were a lot of interesting people there. Nick Cave was putting the Bad Seeds together and writing his novel. There was Malaria! and a band called Die Haut. It was an interesting but lonely time in a way. I was just semi-channeling those things but not in a super specific way. I’m not able to talk about it because it’s intuitive. It’s mysterious to me, but yes, there was something feeding it.

In the same way regarding “John Ashbery Takes A Walk” [featuring Charlotte Gainsbourg], I loved the New York School poets, I studied with them, and Carter’s into them. We worked together with Ron Padgett on our film Paterson, [he] wrote poems for the film. There was this piece, and I just thought, the working title is “John Ashbery Takes A Walk” because it was an ambulatory, psychedelic track, not super heavy, and then that developed into having John Ashbery’s poems being read by Charlotte Gainsbourg. It’s a little mysterious how these things come to us. It’s hard to be precise about their origins, but certainly, there are threads that we refer to as inspiration.

Beautifully read, of course, by Charlotte Gainsbourg, who you could really have read anything, and it would be transfixing.

Jim: She could just read the phone book, literally, I would just listen to it. When we first got her tracks, I just kept listening to them alone without the music for quite a while because I was just mesmerized by them.

In many ways, Silver Haze plays a “blind” soundtrack, as opposed to a silent film. After having made films for so long and using music as an inspiration for the images, was the opposite freeing?

Carter: For us, it’s a very different process…making music for a film versus making this music that didn’t have anything to do with a particular film.

We don’t sit and play along to the films when we do this, but we have this kind of deeper understanding of what exactly the music is, and the music is intended ultimately to serve a function in a larger piece of art, a larger work. This is very freeing in a certain way and really makes you think pretty hard because you’re evaluating how the different songs fit in relationship to each other. Ultimately, the work is an album in this sense. When we play live, it’s a set list, but in this sense, the songs need to have some kind of relationship to each other, and hopefully, in a way, they tell some kind of story. Although we don’t know what the story is.

Jim: Creating music for the film without it being a specific cue, for me, it’s similar in that I’m thinking about the atmosphere of the film and the characters and the place and the photography, the colors or lack of whatever. It’s not so different. It’s just that one’s going to be eternally tied to the image. Although you can listen to our score of Only Lovers Left Alive music without the film, but you can’t watch the film without the music. It’s created to be woven together. That’s really the only difference for me, and it’s not a very good answer.

The album also features Marc Ribot, who you worked with on Down by Law. Did you approach him to do both tracks he’s featured on?

Carter: Marc is just a phenomenal guitar player who we brought in at the suggestion of Randall [Dunn], actually. Randall had worked with him in the past. He knew that we had some connection, but really, more than anything, he could hear Marc’s voice and understood how he might collaborate with us on these things. We brought Marc into the studio, and he is just such an incredibly adept and intuitive guitar player that when we sat him down and said, “Do you want to listen to the tracks first, or do you want to listen back to these that we’re thinking about having him planned?”, he said, “No, no, no, just record. Hit record. I’m ready to go.”

After futzing with a few pedals and getting him some nine-volt batteries, he was just off to the races and laid down the most incredibly varied and lyrical and at times angular and other times very flowing guitar lines. He plays a solo on a third of [the songs]. In the case of ”Garden of Glass Flowers,” it really becomes the lead because the rest of the music is all actually very percussive. I think Jim maybe can speak to the unique way that he treated and employed his guitar parts on that track, which are very different from Marc’s.

Jim: I gotta add, Marc did dictate what was on “Il Deserto Rosso.” He did two or three takes only. He did not want to hear the music first. He said, “Just roll it. I’ll react to it. I know Sqürl. I know you guys.” Then he did maybe three takes that were all entirely different. The last one, he was playing his guitar with his house keys, and they were all so beautiful but different. I like to think of Marc as a hired gunfighter. He’s very focused, and he comes in and does the job, and then he is gone. He is just remarkable.

Can you tell me about approaching Anika for the track “She Don’t Wanna Talk About It”?

Jim: We saw [Annika Henderson’s] band, Anika, play at the Sacred Bones [record label] 15th anniversary [event] where a lot of their bands played, including us. Anika played, and we were just like, “What the hell? She’s incredible.” It’s not anyone else. Of course, there are strains of Nico and things in her work and trip pop and different things and a minimalist approach. She just was mysterious and captivating and musically…we loved her.

Carter: Anika was one of those artists that really defined a lot of it for us. She was a part of it, and she’s such a fascinating and versatile artist…

Are you talking about yourself in “The End of the World,” in reference to the older man approaching 70?

Jim: Well, I am. That song is somewhat inspired by my daughter, who’s a teenager. Teenagers are guides, always, for culture and music and art. They’re the ones that start the ideas that then become things like rock and roll and hip-hop. They’re Joan of Arc and Rimbaud and Mary Shelley. These people are super important to me. It was myself looking at something abstract that I was imagining, and I just read that text in the studio while Carter and Randall were shaping the tracks. Then I was scribbling away. They didn’t really know what I was doing.

Then I said, “Yes, I wrote this thing inspired by these tracks.” I read [the lyrics] to them, and they said, “Yes, record them.” It was not a planned thing. It just was evoked by the music somehow. Thinking about the war in Ukraine. It just started. I was thinking about teenagers in the future and all these things. I don’t know exactly, but it came from listening to the music, and all those things came swirling around. It’s a personal view of the world in a way.

Tell me about the album cover, which was photographed by your brother, Tom Jarmusch. It reflects the inherent beauty of damage.

Jim: I think that’s true. My brother always finds beauty in broken things. They become sometimes, in this case, a bit abstract. He did the cover of an EP we did for Sacred Bones some years ago called EP #260, an instrumental-heavy, stoner-metal thing that we did. That also had an image that’s a realistic photographic image, and yet he finds these things that become slightly abstracted or dreamlike. Not by being “prettified,” but by being broken. I don’t know how to describe it, but he’s a very particular eye and aesthetic that I love, and it seemed appropriate to our music.

Carter: Both the landscapes that Tom chooses and gravitates toward have this bleak beauty to us. I think it comes from the fact that Jim and Tom, also myself, grew up in the post-industrial Midwest or have some affinity for it. To us, gray and plain and empty has a certain beauty to it.

Then, Tom’s aesthetic can often lead towards beauty and damage. This particular element that we used is the negative of a polaroid…the emulsion is torn in places. There’s dirt stuck to it, indefinitely. We wouldn’t have dared try and clean any of that off. It is the image.