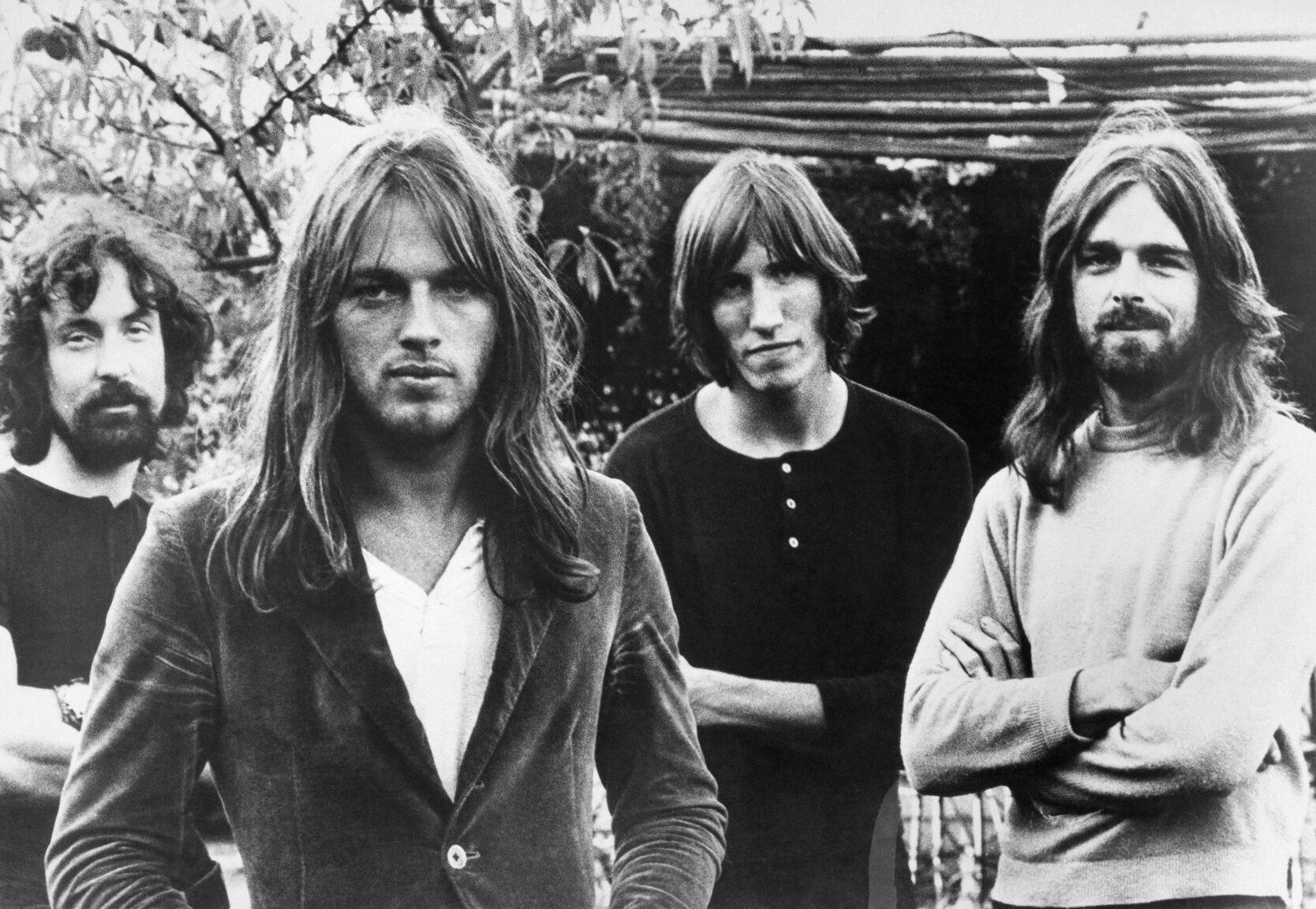

In March 1973, the London quartet Pink Floyd released The Dark Side of the Moon, an enigmatic but richly melodic concept album about madness and mortality. Since emerging during the 1967 “summer of love” with its proto-psychedelic debut, The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, Pink Floyd endured the departure of troubled frontman Syd Barrett and released a series of expansive, improvisatory albums that made it a rising star of the progressive rock movement. In a matter of weeks, however, Dark Side transformed the members of Pink Floyd into transatlantic superstars, despite the band’s aversion to interviews or appearing on its album covers.

Dark Side spent only one week at No. 1 on the Billboard 200, knocking Alice Cooper off the top of the chart before being replaced by Elvis Presley. But its staying power has been both remarkable and record-breaking, having now spent 974 weeks on the tally in one form or another.

The mind-boggling scale of the album’s success does little to explain its enduring mystique, from its hypnotic melodies to its haunting, philosophical lyrics. For decades, fans have listened to it at planetariums and laser light shows or synced it up to the 1939 film The Wizard of Oz as an urban legend-fueled dorm room pastime, despite all evidence that Pink Floyd never planned such a stunt and any synchronicity is purely coincidental. In fact, the only things the band watched together during sessions for the album were football matches and Monty Python’s Flying Circus.

Also Read

The 10 Best Live Prog Rock Albums

With the landmark album now half a century old, Pink Floyd is marking the occasion with the publication of The Dark Side of the Moon: The Official 50th Anniversary Book as well as a deluxe box set. Bassist Roger Waters, who was ousted from the band in 1985 but still plays its music to massive crowds as a solo artist, has even been working on a complete re-recording of Dark Side, without any participation from his famously feuding bandmates. Here’s SPIN’s breakdown of how each of the 10 tracks on The Dark Side of the Moon was made, and all the mundane, profound, and serendipitous details that led to one of the most fascinating and unlikely blockbusters of the 1970s.

1. “Speak To Me”

In May 1972, Pink Floyd commenced nine months of sporadic sessions for its self-produced eighth album at Abbey Road, the EMI Records-owned London studio favored by the Beatles. The first few Pink Floyd albums had been recorded there, but the band tracked 1971’s Meddle elsewhere due to the limitations of the studio’s eight-track mixers. When that equipment was upgraded to 16-track, Pink Floyd agreed to return to work on what was planned as an album of shorter songs with segues, in contrast to the increasingly ambitious, 20-minute epics such as “Atom Heart Mother” and “Echoes.”

The 65-second track that opens Dark Side is both an overture and a collage, combining sounds from the songs that would follow (the cash register from “Money,” Care Torry’s vocal from “The Great Gig in the Sky”) with spoken vocals. Pink Floyd bassist Roger Waters wrote down a series of questions on cards about sanity and mortality that were linked to the lyrics he’d written for the album, and a multitude of associates of Pink Floyd and people passing through Abbey Road sat in a vocal booth and answered the questions. “Speak to me” was what EMI staff engineer Alan Parsons would tell the interviewees in the vocal booth as he was testing audio levels, and that phrase ultimately became the title of the track.

A card that asked “Do you think you’re going mad?” prompted roadie and production manager Chris Adamson to say some of the first words heard on the album: “I’ve been mad for fucking years, absolutely years. I’ve been over the edge for yonks, been working with bands so long.” One of the men who’d made Abbey Road famous, Paul McCartney, was in the building to work on a Wings album and participated in the experiment, but he and his wife Linda’s answers to Waters’s questions were left off Dark Side.

Drummer Nick Mason was given sole writing credit on “Speak to Me,” a gift from his bandmates to cut him in on publishing revenue that would profit him handsomely after the album’s unexpectedly enormous sales. The heartbeat sound that bookends the album on “Speak to Me” and “Eclipse” was created with Mason’s bass drum, which he struck lightly with mallets after an unsuccessful attempt to use the sound of an actual human heart.

2. “Breathe (In the Air)”

“Breathe” had the longest gestation of any song on Dark Side. A markedly different acoustic version appeared on Music From The Body, the 1970 album by Roger Waters and Scottish composer Ron Geesin, featuring music recorded for Roy Battersby’s documentary The Body. Waters was influenced by Neil Young’s “Down by the River” in writing “Breathe,” while keyboardist Rick Wright credits “All Blue” from Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue for inspiring the chords he played on the song.

The sad psychological decline of Syd Barrett was an obvious inspiration behind Dark Side’s lyrical themes, but he also influenced the music: “Breathe” is played in the open G tuning that Barrett had taught to his bandmates. When Dark Side was first released, the second track was titled simply “Breathe.” When the album was issued on CD in 1985, the title was changed to “Breathe in the Air,” and later amended to “Breathe (In the Air).”

3. “On the Run”

During the early stages of development, the instrumental “On the Run” bore the working title “The Travel Sequence.” Airport announcements and plane crash sound effects introduced some sort of flight mishap to the album’s narrative, tying into Wright’s fear of flying that inspired “The Great Gig in the Sky.” Roger Manifold, another Pink Floyd roadie responding to the Waters questionnaire used in “Speak To Me,” delivered a spoken interlude: “Live today, gone tomorrow, that’s me.”

The sheer variety of different sounds in “On the Run,” including backward guitar parts and a hi-hat pattern generated by an EMS Synthesizer, made it one of the most difficult songs on the album to mix. The track required six people’s hands on the mixing board at once: Parsons, assistant engineer Peter James, and every member of Pink Floyd.

4. “Time”

During Pink Floyd’s early Barrett era, Wright was the band’s second-most prolific singer and songwriter, penning tracks like “Paint Box,” “Remember a Day,” and the single “It Would Be So Nice.” With the addition of guitarist David Gilmour and the emergence of Waters as the band’s creative leader, however, Wright’s vocal and lyrical contributions became less frequent. While Wright wrote or co-wrote music for five tracks on Dark Side, “Time,” on which he and Gilmour both sing lead, would be the keyboardist’s last lead vocal on a Pink Floyd track until The Division Bell two decades later.

The variety of clock sounds that open “Time” were recorded by Parsons, who took a portable Uher recorder into a watchmaker’s shop as part of an effort to collect audio for the studio’s sound effect library, as well as for a demonstration of its new quadrophonic sound system. Upon hearing the track with the working title “Time Song,” Parsons offered the clock sounds to the band.

5. “The Great Gig in the Sky”

A few months before Pink Floyd began sessions at Abbey Road, it workshopped the new material at a series of shows. At the Brighton Dome in January 1972, “The Great Gig in the Sky” still had its working title, “The Mortality Sequence,” and would later temporarily bear the title “Religion.” It would be the last time that the band played a new album extensively before its release, however. A bootleg of those preview performances, Tour 72, began circulating before the real album and sold more than 100,000 copies, which likely helped build anticipation for Dark Side but certainly displeased the band.

While most of the performances on the album had been recorded during the initial 1972 sessions, the most iconic guest appearance on Dark Side, from “The Great Gig In The Sky” singer Clare Torry, was a last-minute addition. Torry was hired by Parsons in January 1973 after the band had brought in engineer Chris Thomas to oversee the final mixes of the album, and her wailing vocal was tracked just six weeks before Dark Side hit stores. Torry received a fee of £30 at the time. In 2005, however, she took Pink Floyd and EMI to court to ask for songwriting credit and compensation. Torry received an undisclosed settlement and is now billed as Wright’s co-writer on the track.

6. “Money”

Pink Floyd spent several days of the sessions for 1971’s Meddle recording anything but conventional instruments, making sounds by opening bottles, tearing paper, or hitting furniture. This experimentation set the stage for the instantly recognizable collage of coins, bills, and a cash register that opens Dark Side’s most famous song, “Money.” The tape loop assembled by Waters had seven beats, setting a rhythmic pattern for the band to play “Money” in its distinctive 7/4 time signature. Two of the voices answering the Waters questionnaire at the end of “Money” are road manager Peter Watts and his wife Patricia, the parents of future movie star Naomi Watts.

While hit singles often drove album sales in 1973, Dark Side was a rare example of a runaway success before a single was even released. It had already sold a million copies by the time “Money” appeared as its first single in May, with the song quickly entering the Hot 100 and peaking at No. 13 by the end of July. It would remain the band’s only U.S. chart hit for six years, until “Another Brick In The Wall, Pt. 2” rocketed to No. 1 around The Wall.

In the fall of 1973, Pink Floyd briefly attempted to follow Dark Side with an album entitled Household Objects using the same musique concrete techniques from the “Money” intro. The idea was eventually abandoned in favor of a more conventional follow-up, 1975’s Wish You Were Here, although the experiments with wine glasses can still be heard on that album’s “Shine on You Crazy Diamond.”

7. “Us and Them”

“Us and Them” has roots in a Wright-composed piano instrumental called “The Violence Sequence” for the climactic scene of Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1970 film Zabriskie Point, which the director rejected as “too sad” and replaced with a different Pink Floyd track in the scene. Revived for the Dark Side sessions, Parsons improvised a device with a modified eight-track mixer to create the distinctive echoing vocal delay on a new version of the song.

“Us and Them,” like “Money,” features saxophonist Dick Parry, a friend from Gilmour’s early days of playing in bands in Cambridge. Despite the large assortment of sung and spoken voices on the album, Parry is the only person besides the members of Pink Floyd who plays an instrument on Dark Side. He performed with the band throughout the subsequent tour and would later appear on Wish You Were Here and The Division Bell. “Us and Them” also features backing vocals by Doris Troy, Barry St. John, and Liza Strike, all of whom also sang on John Lennon’s 1971 single “Power to the People.”

8. “Any Colour You Like”

Although virtually every Dark Side track became a staple of classic rock radio, “Any Colour You Like” has garnered the least airplay of any of them, which is ironic given that it appeared on the B-side of the “Money” single. Due to Gilmour’s wordless scat singing on the instrumental, its working title on setlists was “Scat.” The final name came from a running joke between the band and Chris Adamson, the roadie whose voice opens the album.

9. “Brain Damage”

Trippy early songs like “Interstellar Overdrive” and “Set Controls for the Heart of the Sun” led the music press to tag Pink Floyd’s music as “space rock,” and Dark Side’s title and public unveiling at the London Planetarium certainly helped reinforce that notion. Waters, however, always hated the term and refuted the idea that the band wrote about literal outer space, telling the Huffington Post in 2013, “It was never about anything but inner space.” That sentiment is backed by “Brain Damage,” which was nearly titled “The Dark Side of the Moon” and contained the album title in its lyrics, which are more about a metaphorical line between sanity and insanity than an actual celestial body.

10. “Eclipse”

The working title for the album was briefly changed to Eclipse: A Piece For Assorted Lunatics after Pink Floyd got wind that the British blues rock band Medicine Head had named its 1972 album Dark Side of the Moon. Once the Medicine Head album came and went with no chart impact, however, Pink Floyd decided to go back to the original title. So “Eclipse” was nearly the album’s title track, and was also nearly a longer multi-part suite encompassing six songs on the album (“Breathe,” “On the Run,” “Us and Them,” “Any Colour You Like,” “Brain Damage,” and “Eclipse”).

“Brain Damage” and “Eclipse” mark the first time on Dark Side that Waters takes a lead vocal and delivers his own lyrics. But the last word on the album belongs to Abbey Road doorman Gerry O’Driscoll: “There is no dark side in the moon. Matter of fact, it’s all dark.”