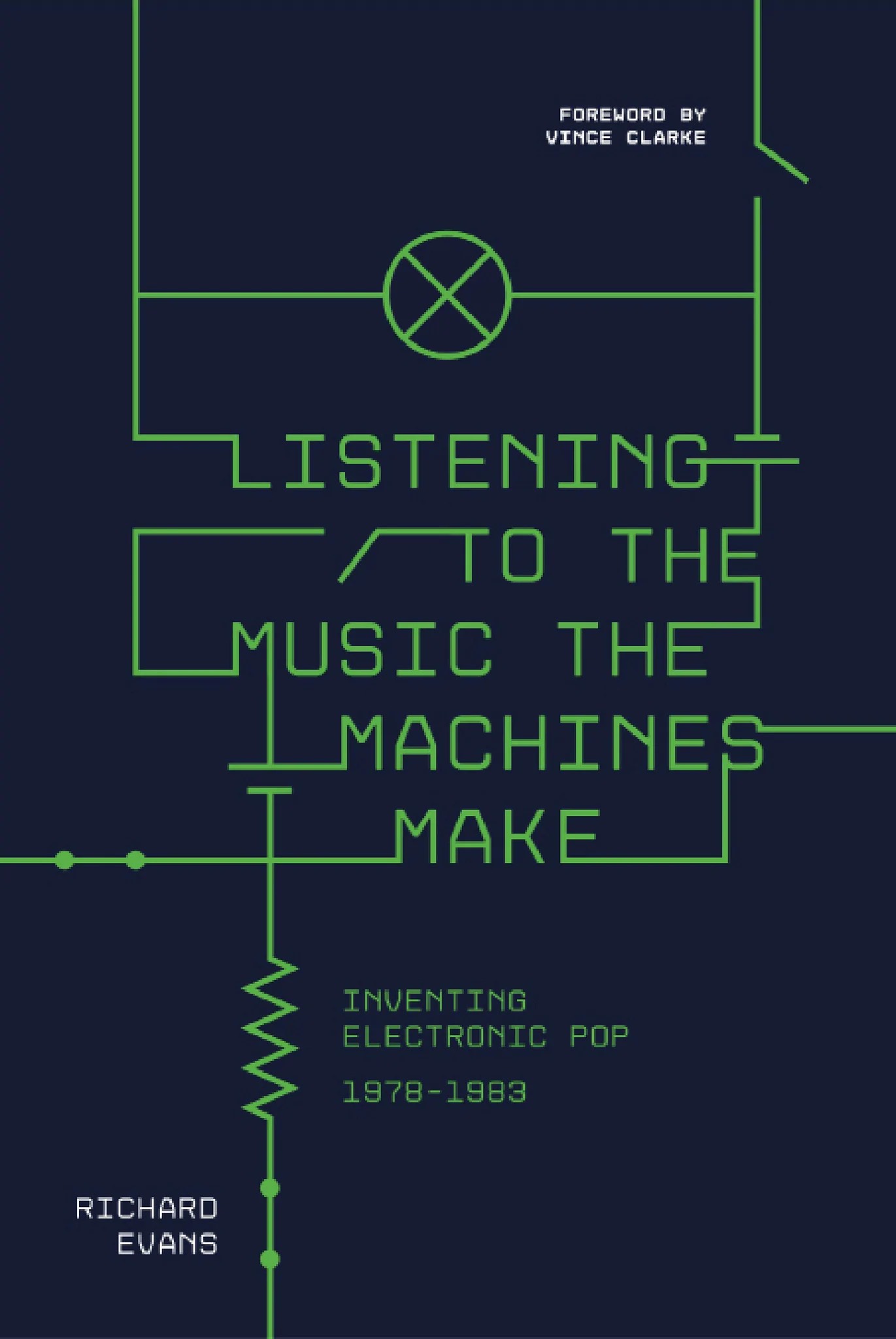

In the UK, the rise of electronic music began in the late ‘70s, which is where Listening to the Music the Machines Make: Inventing Electronic Pop 1978-1983 starts. At over 500 pages, with a foreword by pioneering electronic pop musician, Vince Clarke, this hefty tome is a terrain view-map of this five-year period, flagged by landmark moments in music. The influence of Kraftwerk on British new wave artists, the pop culture mecca that was London’s Blitz club, out of which numerous groups were birthed, including Spandau Ballet, the vitriol with which the music press ripped apart albums and singles and the musicians that created them: It’s all woven together with tapestry-like precision.

The work of music industry professional Richard Evans, Listening to the Music the Machines Make is meticulously researched. Evans draws primarily from the music press of the time, and to a lesser degree from biographies and documentaries, piecing together a complete picture of this crucial period. Evans makes smooth transitions between key artists, albums and pop culture, clearly showing this timeframe’s influence on the music that followed.

Evans himself doesn’t profess to have been on the cutting edge of new music in his teenage years, however, the early part of which lines up with where Listening to the Music the Machines Make starts. “I’m not going to pretend I immediately discovered The Normal or Fad Gadget or the early albums from The Human League,” he says, “but I found them retrospectively. In fact, I didn’t identify myself as a particular fan of electronic music for a long time, although looking back I can now recognize a very definite common electronic thread running through the various music that was catching my attention at that time.”

Published in the UK in November 2022 to a slew of favorable reviews, Listening to the Music the Machines Make was proclaimed Book of the Year by Classic Pop Magazine and Blitzed Magazine. The book was recently published in the United States and is a must-read for those whose formative years overlap with those of the book’s, as well as those who are happily cribbing from the music of this era without any context for it. And if you consider yourself a music scholar, or lover, this book is essential for your reference shelf, the amount of space it takes up being equivalent to the cache it brings you.

SPIN: It’s clear gathering the information was a massive task. How did you tackle the actual research?

Richard Evans: It was the part of the whole process that I enjoyed the most. The majority of the research was done at the British Library in London which is one of my favorite places to be. You can go to the appropriate reading room and pull down these massive bound volumes of music press titles from the past. Each one will contain three months of issues of Melody Maker or the NME or whatever title you want to look at. I spent days and days at the British Library working through all the issues of every music or popular culture title I could find covering 1978 to 1983. Every time I found a mention of something that I thought might be useful, I took a photo of the page with my phone. I ended up with literally thousands of photos of news stories, interviews, features, reviews and adverts. It was a bit like having a gigantic box of jigsaw puzzle pieces. The process of writing the book was like putting the jigsaw together.

Media in the UK had a lot of power, although their proclamations didn’t always dictate how an artist fared. What are your thoughts on the power of the media and its impact?

The UK music press at this time was incredibly powerful and influential, but in the immediate post-punk years it lost its way. Partly that was because they were looking for a new movement to champion after punk and they were spoilt for choice. The late ‘70s were very exciting musically. There were lots of new things happening. The electronic revolution ran parallel to the new wave success of bands like Blondie and Elvis Costello as well as two-tone’s ska revival, and bands like the Stray Cats were having a lot of success returning to rock ‘n roll.

Against all that activity, I think that electronic music was too new for established journalists, many of whom came from a previous generation and, despite punk, were still deeply suspicious of upstart bands that hadn’t spent years honing their craft and paying their dues, instead relying on technology to generate their sounds. That said, the early pioneers, bands like The Human League and Devo for example, were briefly lauded—enough for those acts to find an audience to connect with—but often only so the media could then tear them down again.

Perhaps nothing had more of an impact on an artist’s success than Top of the Pops.

Top of the Pops was so exciting during those years. Outside actually attending a concert—something that was frequently impossible—it was pretty much the only place where you could see bands perform. At the time, there were only three TV channels broadcasting in the UK, [which] meant the audience for each show was in the millions every week ensuring that Top of the Pops‘ influence was simply unparalleled.

You drew from a lot of musicians’ biographies. Did you read all of them?

I did. In fact, when I first started to plan the book, I was intending to approach as many of the artists as I could to ask them about their memories of this period and to work from those contemporary accounts. But it was reading the various autobiographies that made me switch my approach to using the music press reports from the time instead. I started to notice inconsistencies creeping into their accounts, which is understandable as they were viewing events 30 or 40 years later. I was more interested in exploring how things were received at the time, which is what led me to the idea of working from the original press accounts instead.

Why did you choose to keep the focus only on what was happening in the UK?

The period 1978 to 1983 broadly correlates with my own journey of musical discovery, so a lot of the records and bands I write about were already close to my heart and as a result I felt confident I could do the subject justice. From a more practical point of view, I didn’t have access to international research materials in the same way I did to UK resources, and I didn’t want to have some parts of the book under-researched in comparison to others. More prosaically, I didn’t have the space in the book to expand my parameters to include international stories. That said, if international artists were successful or influential here during that period, people like Devo, Sparks, Suicide, Telex and Yello, I tried to include them.

There is marked impact of German-created and -influenced music during the timeframe the book covers when the Berlin Wall was still up. Why do you think that Germany was so impactful?

I think that maybe it’s because after World War II Germany was keen to distance itself from its own past. As a result, there was a desire among young German musicians to make something new, something that wasn’t built on the echoes of the past, and how better to do that by focusing on the newest musical technology of the time which had no ties with the past? In turn, that newness tapped into the broader spirit of those times, a period when great technological breakthroughs were being made. If you were growing up at a time when it felt like science fiction was being brought to life then it made sense that the soundtrack to all those things should be equally new and exciting.

There was an honesty, sometimes “savage,” as you say, that is not always present now. Do you feel like that cautiousness will stop an accurate picture of music being captured?

I do, and I don’t. I do agree that there is a blandness to a lot of the contemporary music press but I wonder if that’s because there’s a struggle for the music press to remain relevant against the backdrop of how music is consumed today. When I became interested in music at the very end of the ‘70s, I often read about bands in the music press way before I heard them because listening to their music was much more difficult back then. John Peel aside, the most interesting bands weren’t played on the radio and records were too expensive to gamble my pocket money on without hearing them first, so the press was really important. Today, you can hear about something you like the sound of and stream it instantly so maybe it’s not as important for music writers to work as hard to convey their passion (or distaste) for something. So rather than trying to distill the energy and excitement of the music into their writing, their function is more curatorial.