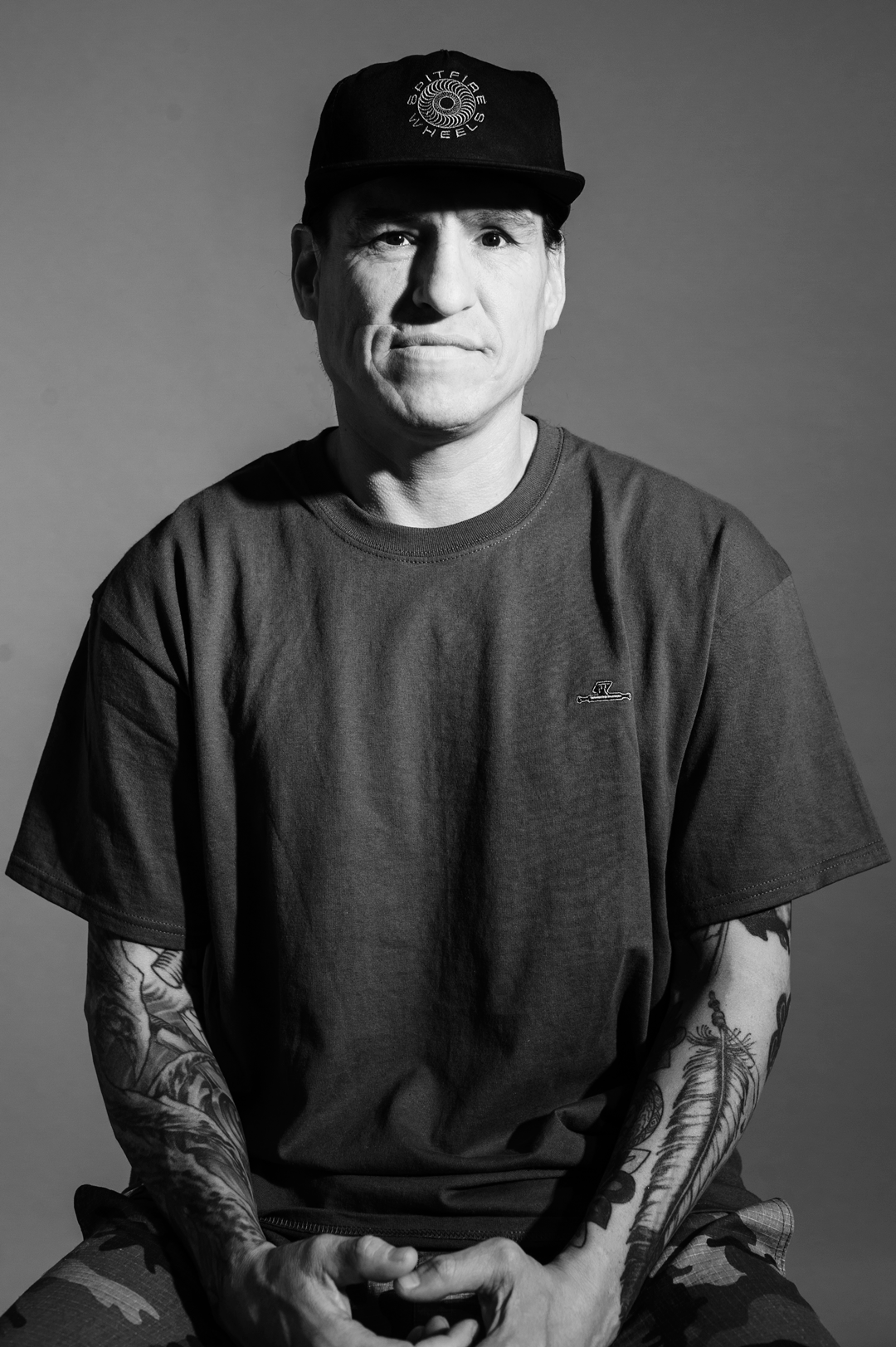

Joe Buffalo looks content this rainy morning. His lanky 6’2” frame fills the bench across from me in the buzzing Vancouver coffee shop. Long jet-black locks of hair escape underneath a cap that shades a steady gaze.

It’s the countenance of someone finally finding what they want in life. “All of the dots are there,” he says, looking up, pointing in the air. “They’re right here in front of me and all I need to do is reach out and connect them.”

These days, there are many dots for Buffalo to connect, doors and opportunities that have opened up over the past few years, but there are chapters in the 46-year-old’s storied life when there weren’t any dots at all.

Buffalo is from Samson Cree Nation and was raised in the small prairie community of Maskwacis, Alberta. (Maskwacis means “Bear Hills” in Cree.) And like his parents and grandparents before him, Buffalo attended a residential “school,” a grossly inappropriate term for the church and government-approved and -administered abuse and murder of thousands of Indigenous children across Canada and the United States.

Buffalo was one of the last generations to attend this abhorrent institution, which included five long years at two locations. To cope with the trauma caused by his time there, the recovering heroin addict ultimately embraced the freedom of the skateboard that he first discovered watching his cousin skate, particularly when he landed his first ollie.

Since he started skating, there were periods when the board would stop rolling and he’d turn to substances and partying for escape. Now clean, sober, and pro with Colonialism Skateboards, Buffalo is harnessing the sport that saved his life to help future Indigenous generations through Nations Skate Youth, a Vancouver-based non-profit he helped co-found in 2020.

“We just want to give back,” he explains. “To have a platform where we could help empower these youth – through skateboarding and the power of it…there’s so many positive avenues you can go down.”

Over the past few years, Buffalo and his team of teachers and mentors have helped hundreds of pre-teens and young adults find their own paths through skateboarding, mentorship and generosity; during that time, they’ve donated thousands of skate decks to, and built several skate ramps for, Indigenous communities across North America.

One of those people who has been there skating with him from the beginning is Rose Archie, one of the four co-founders of the organization. Their bond and idea for Nations Skate Youth was born when she invited Buffalo to talk to youth about mental health and skateboarding in 2019. After talking and finding a connection, they realized that this could be a long-term endeavor, one that could make a lasting, positive impact.

“We all knew this would be something bigger than just a one-time thing,” she remembers. “That meeting was the beginning of Nations Skate Youth and a dream come true.”

That dream is making a difference in young people’s lives, fueled by the aspiration to be a rad role model for these young shredders.

“I try to be the person I wanted to meet when I was young, someone welcoming and accepting. I met so many friends along the way and I hope to inspire others to do the same.”

When asked about what it’s like seeing a young person make that special connection with the skateboard, Buffalo’s face breaks into a big smile.

“It’s the best,” he says. “None of that energy is forced – you can’t force that natural reaction to happen on its own. To see the kids’ reactions and how stoked they are when they figure a trick out for the first time…it’s incredible.”

There were times in the past when Buffalo did not understand the pivotal role skateboarding had in his life, underestimating the natural talents he was given to change not only his own life, but others, as well.

“I treated my skateboard like a boomerang,” says Buffalo, who skates streets all over the world to the beats of artists like Nipsey Hussle and M.O.P. “When I would toss it away, it would somehow make its way back to me, years later. A lot of people toss it away and it never returns ever again so I’m super grateful that it’s been with me ever since.”

“I’ll never toss it again after what I’ve been through,” he adds.

Like Buffalo, Rose says skateboarding has continued to nourish her life and relationships, taking her to never-ending new places and people while maintaining a strong link to her heritage.

“With Nations Skate Youth, my message to the youth is to be proud of who you are and where you come from,” she says. In 2013, she started an all-women’s skate jam called “Stop, Drop, and Roll,” which brings together girls, women, trans, non-binary and/or gender non-conforming skaters. “For me it’s connected me back to my culture and to keep my traditions going that I have learned growing up.”

It’s this message of pride in who you are that rings loud in “Joe Buffalo,” a short documentary that he wrote about surviving and thriving through skateboarding in spite of a traumatic past.

Distributed by the New Yorker and executive produced by Tony Hawk, the acclaimed film has made Buffalo a somewhat reluctant spokesperson, for which he feels some emotional pressure.

“It’s there, 100 percent, every day,” he says, shrugging his shoulders slightly. “People run their opinion [about residential schools] by me all the fucking time. I want to educate people but it’s hard doing that 24/7.

“It’s a part of healing for me…just talking about it,” he says. “I want to educate the world with these stories.”

There’s a certain scene that stands out for me from Buffalo’s documentary. It shows him holding his first pro model deck with a graphic of his famous grandfather, Cree Chief Pitikwahanapiwiyin, or Poundmaker, a ground-breaking design that’s also a dream come true.

“I dreamt of this when I was kid, since I was eight years old and I learned that I was related to him,” he says, still in disbelief.

He looks up and has that big smile on his face.

“Yeah…it actually happened.”