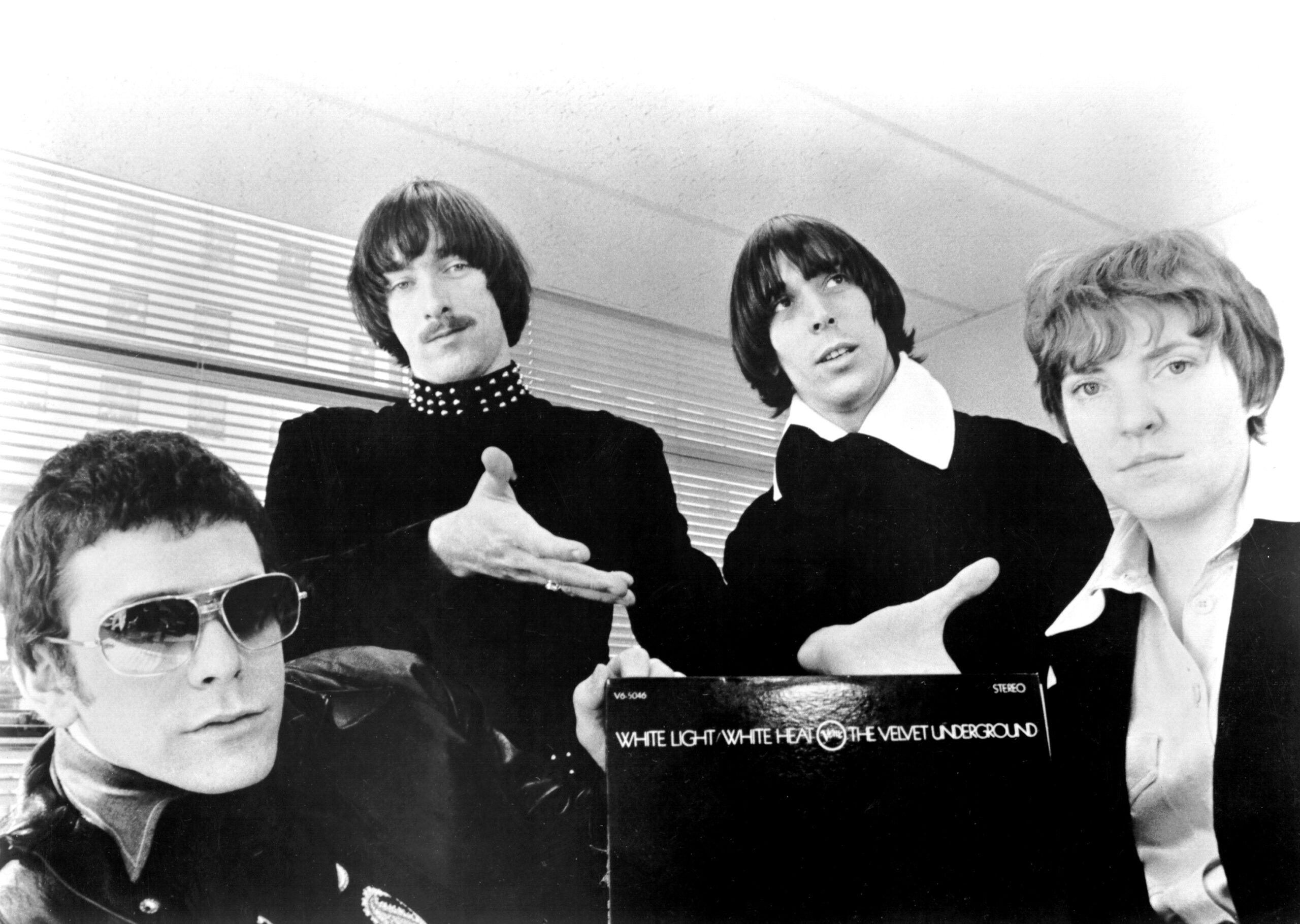

John Cale didn’t come to popular music from the usual places. His muse was born in the classical avant-garde, and when the young Welsh musician first arrived in New York in the early 1960s, he was pulled first into the evocative drone sounds of La Monte Young, joining on viola the composer’s Theatre of Eternal Music (a.k.a. the original Dream Syndicate). Then he met Lou Reed and became excited with the possibilities of a new kind of pop music, colliding all he had learned in the uncompromising avant-garde with Reed’s literate, highly crafted rock songs, and the Velvet Underground was born.

Their collaboration would remain sporadic through the decades — Reed fired Cale from the VU after their second album, and they’d come together only occasionally after that, most meaningfully on 1990’s Songs for Drella. But for Cale, the Velvets were only the beginning of a long exploration of boundary-breaking popular music as a recording artist and as an album producer of essential debuts by the Stooges, Patti Smith and the Modern Lovers, among many others.

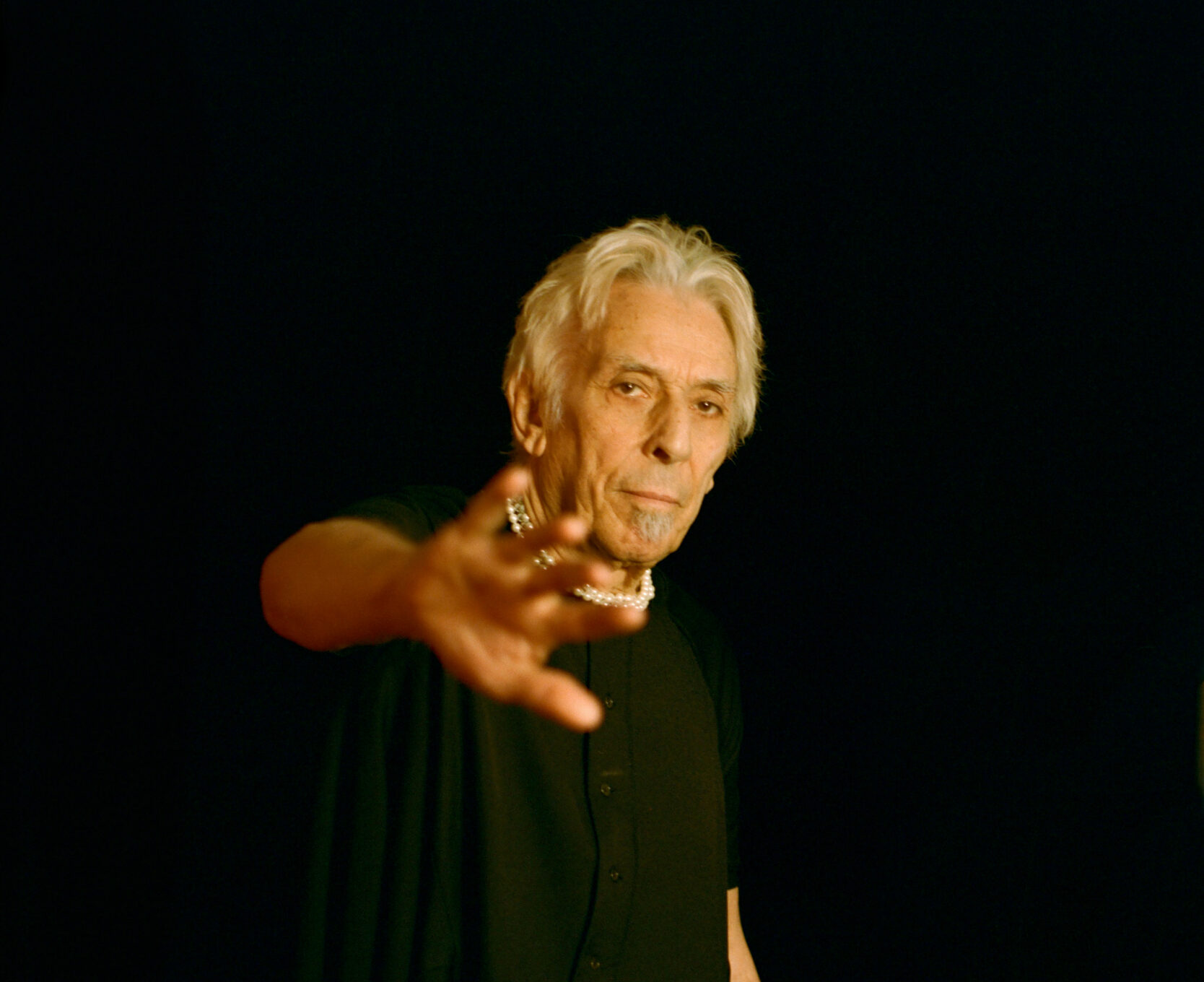

Now 80 and based in Los Angeles, Cale has managed to maintain a vibrant career in his own lane without too much struggle, to the tune of 17 studio albums and countless live recordings. He also managed to help turn Leonard Cohen’s previously obscure “Hallelujah” into a modern standard, stripping it down to solo piano for a 1991 Cohen tribute album, I’m Your Fan (instigated by French magazine Les Inrockuptibles). It has since been recorded by hundreds of artists, from Jeff Buckley to Willie Nelson.

On his new album, the just-released Mercy, Cale is still leaning forward, collaborating on most of its dozen tracks with a later generation of artists, from Actress and Weyes Blood to Sylvan Esso and Animal Collective, arriving at something dreamy and post-modern. It’s his first new studio album in a decade, and it emerged from the long isolation of COVID-19. Under lush layers of organic and electronic sound, and with Cale’s distinctively commanding, subtly emotional vocals, there are songs about people he’s known — including Nico (“Moonstruck (Nico’s Song)”) and David Bowie (“Night Crawling”) — and people he didn’t, notably on “Marilyn Monroe’s Legs (Beauty Elsewhere).”

The recent Todd Haynes documentary, The Velvet Underground (available on DVD and Blu-ray) told his troubled origin story in Wales with new poignancy, and Criterion is currently streaming the restored film performance of Drella (directed by Edward Lachman). So his history is out there, continuing to influence modern music in untold ways, but Mercy suggests he’s still ready for more.

SPIN: Todd Haynes’ Velvet Underground doc really tells your early life story, from your childhood in Wales to your arrival in New York. It gives a sense that you were on a path towards something, regardless of whether you ever connected with the band.

John Cale: Yeah, I was kind of driven. I was determined to get somewhere. All along the way from Wales to New York, it was crowded with people that I really wanted to work with. And eventually, New York was the apex. I’d managed to talk to three or four contemporary composers, and they helped me get a clear idea of what was happening in New York, what was happening in Berlin, what was happening in Wiesbaden, and what was happening in L.A. Eventually out of the crowded field, I got to New York and spent a good year and a half working — I played viola in Le Monte’s trio. I made choices as to whether I was going to do the European thing with Stockhausen, which Le Monte had already done. And I decided “No, I’m going to try and work on what is the American experience in contemporary music.”

What drew you to the avant-garde side of things at a young age?

It was really exciting to do the avant-garde. I understood what the roles were for Aaron Copeland and a bunch of really European composers, and Europe has a documented history of advanced thinking in music. I thought it would be interesting to find out what other groups of people from different parts of the world and their idea of what avant-garde meant. What you’re really looking at is how people share conversations, in the sense that there’s a conversation going on between the composer and the audience. These generate other feelings and other ideas. I ended up paying attention to John Cage. They say that Le Monte was the most interesting American musical composer and that he was working and deliberating in different arenas than Stockhausen would. The whole European thing was hung up in intonation — in how melodic and chordal developments in the music were really stuck in one place.

Those first two albums with the Velvet Underground were very experimental and avant-garde but within the context of popular music. How did you feel about colliding with those two worlds?

That was essential. When I ran into Lou, I realized this was something that we can do. This is something that really nobody is doing. We’ve got somebody who can improvise lyrics and talk about what was funny about what had happened that morning. And then with it, there was some rock and roll. I thought, wait a minute, Bob Dylan isn’t the only one who’s doing this. And I wanted to explore that.

This new album is your first in 10 years. Was it a long time in the works?

Everybody got the lockdown, and that really put a spanner in the works. It took me about two and a half years. And when I came out of it, I had written an album and I started thinking “This album has been sitting around for two and a half years, and I’m trying to figure out what I need to finish it off.” I decided to figure out which tracks needed a little attention and which didn’t. I started thinking about other artists that I’d worked with and how they could propel what I had already done further. I’ve got the best parts of the past and the best parts of the future on the record.

There was a process going on here that I was trying to work out something about that would get me out of the doldrums of this pandemic. I moved the music along a little bit further and brought in some artists that were really very helpful in deciding how some of this would work. Animal Collective, for instance, are on the song “Everlasting Days.” I’d worked with them before, and this suddenly became an extended family as time went on. A lot of people were looking forward to doing that because they were fed up with being in hiding in the closet for another two years whilst everybody figured out whether they got the disease or not.

What type of artist is ideal for you as a collaborator? Is there a through line?

There is. I think it really is a partnership. You really get to know people in a different sense. Collaboration to me is really understanding other people’s point of view. And you’ve got to have this creativity going on between the two of you, and if you’re generous about your approach to the music, then you’ll get somewhere meaningful.

One track that caught my attention was “Marilyn Monroe’s Legs (Beauty Elsewhere),” recorded with Actress. What was the genesis of that?

I wanted to have a song about Marilyn Monroe without mentioning her name. Actress was very fast. And it was the most abstract song on the record. I was pleased with everything that happened in the studio with Actress.

Is it different writing a song about someone you didn’t know versus people you did know?

I think I like it that way. The mystery of it is really captivating. When I wrote that song about Nico, it just happened to be something that I had never done. I’d worked with Nico and it happened that it was a good partnership. And so the song about her took a long time to come. I was very happy with it in the end, but I wish I’d done it earlier.

I’m sure you’ve noticed that Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah” has become a standard since your 1991 version. Does it surprise you that it caught on in the way it did?

It’s got a life of its own now. I was happy about it, but I was surprised that it happened so fast. And Leonard was very generous with his help. It all came about in this strange roundabout way. It was this rock and roll magazine from Paris. I really went for that song because it was so simple. There was nothing complicated about how this song worked. It didn’t need a large orchestra. It didn’t need many voices, and it was already self-contained. I went working with some of the other songs that Leonard had, but they didn’t work as smoothly as “Hallelujah.”

At some point, Leonard Cohen said too many people were singing that song.

I understand his point of view. He doesn’t want the attention.

What does it take for you to find someone interesting enough to be inspired to make music based on them?

Well, I’m terrible. I mean, I’ll just make somebody up [laughs] if I don’t have anybody ready at hand. It’s often a very good way of working. The mystery of it all is really what you’re playing with.

It’s always seemed that you were able to do what you wanted and create the music that appeals to you. Was it ever a struggle to find support for what you were doing?

No, it was really finding which style [I was] interested in at the time. There was a time when I decided “OK, I want to do [poet Dylan Thomas’s] ‘Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night’ and arrange it in a different way with an orchestra and do some classical arrangements [on 1989 album Words for the Dying].” And then there were some which were just straight rock and roll punk arrangements. I tried as many different things as I could.

When you were producing other artists for major labels, was there any commercial pressure, like “We’re trying to get a radio song out of this”?

Yeah. Always, always. Some of them would say “Well, yeah, it’d be nice.” Some of them never mentioned it. What are you gonna do?