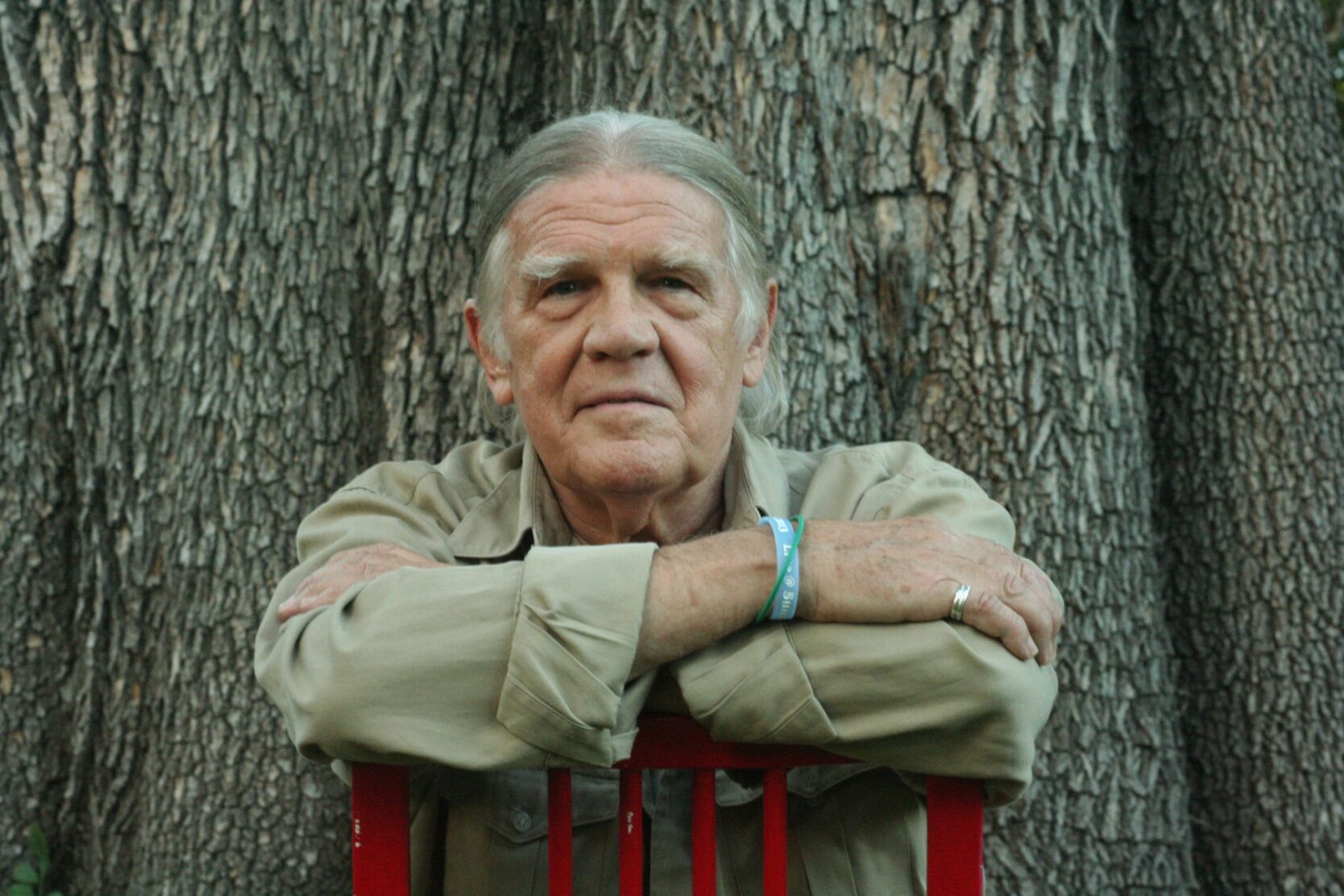

“Can I just tell you how fabulous you are,” a friendly, middle-aged woman with a warm smile says to 84-year-old legendary music photographer Henry Diltz as she walks toward the corner booth of a busy San Fernando Valley diner, where he is eating lunch. With his long white hair pulled back into a low ponytail and his gentle blue-gray eyes looking up at the woman, Diltz smiles, thanks her graciously and asks her name. “My name is Bonnie,” she says, “I follow you on Instagram.” After a brief and pleasant exchange, she says, deferentially, “Sorry to interrupt you” and walks away.

Due to his thousands of social media followers, Diltz says he is often recognized in public, which he appreciates, but not because he seeks recognition. He genuinely loves people. “My feeling is, ‘Wow, this is incredible,’ because it’s a sudden introduction right out of the blue,” he says. “And you never know who it’s going to be or what it’s the start of. It could be angels sending us little hints.”

Cheerful, chatty, and quick to laugh, Diltz is also incredibly humble. He balks when he is referred to as a legend and says, “For a long time, when people would come up to me and say, ‘Oh my God, I love your photos,’ they’d go on and on, and I’d say, ‘I appreciate that you are lauding me and saying wonderful things about me, but you don’t really know me. You’ve seen the pictures I take and you love somebody I photographed. I’m just the guy with the camera, you know.’”

Diltz’s modesty extends to the astonishment he expresses about the Grammy Trustees award that he will soon receive, putting him alongside iconic past recipients including The Beatles, Thomas Edison and Les Paul.

“A part of me says, ‘Wow, that is so great. I’m so grateful,’” he says. “But the bigger part of me is saying, ‘But I didn’t really do anything. I was just having fun doing what I do.’ I’m half-thinking I’ll walk up there and say, ‘Thank you, everybody, but you got the wrong guy.’”

Diltz’s reticence belies his illustrious five-decades plus career. Not only was he the official photographer of the Monterey International Pop Festival and Woodstock Music and Art Fair, but he has shot over 200 album covers, including the Eagles’ Desperado, The Doors’ Morrison Hotel, James Taylor’s Sweet Baby James, and Crosby, Stills & Nash’s self-titled debut. He has also taken thousands of publicity stills and live concert photos of myriad famous musicians, including America, Bob Seger, Jackson Browne, and Linda Ronstadt. His photos have been featured in high profile magazines including LIFE and Rolling Stone (both publications have also featured his photos on the cover), biographies, coffee table books, and gallery shows.

What’s more, Diltz won a Lucie Award in 2015 and, three years ago, was inducted into the International Photography Hall of Fame Museum.

His gift for spontaneously capturing iconic images, without ever having taken a single photography class, is part of what makes Diltz a singular talent. “What I do is instinctive, quiet and naturalistic,” he says. “I want to document unobtrusively. I want to see what people really are. I frame up the situation and then I push the button. I always want it to look exactly the way it looks to me.”

He notes an observation made by actor Harrison Ford years ago. “He said, ‘Henry, you have a framing jones.’ I thought, ‘That’s it. I do.’”

In addition to photography, Diltz is also a musician who plays banjo, clarinet and harmonica. During the ‘60s and ‘70s, he lived in Laurel Canyon where, outside of the West Hollywood music venues he frequented, he met most of his friends, some of whom, like David Crosby and Cass Elliot (a.k.a. Mama Cass), were famous musicians. With music as a common bond, but also because of his unassuming and easygoing nature, the who’s who of musicians have always loved and trusted Diltz intimately, giving him unrestricted access to shoot behind the scenes photos.

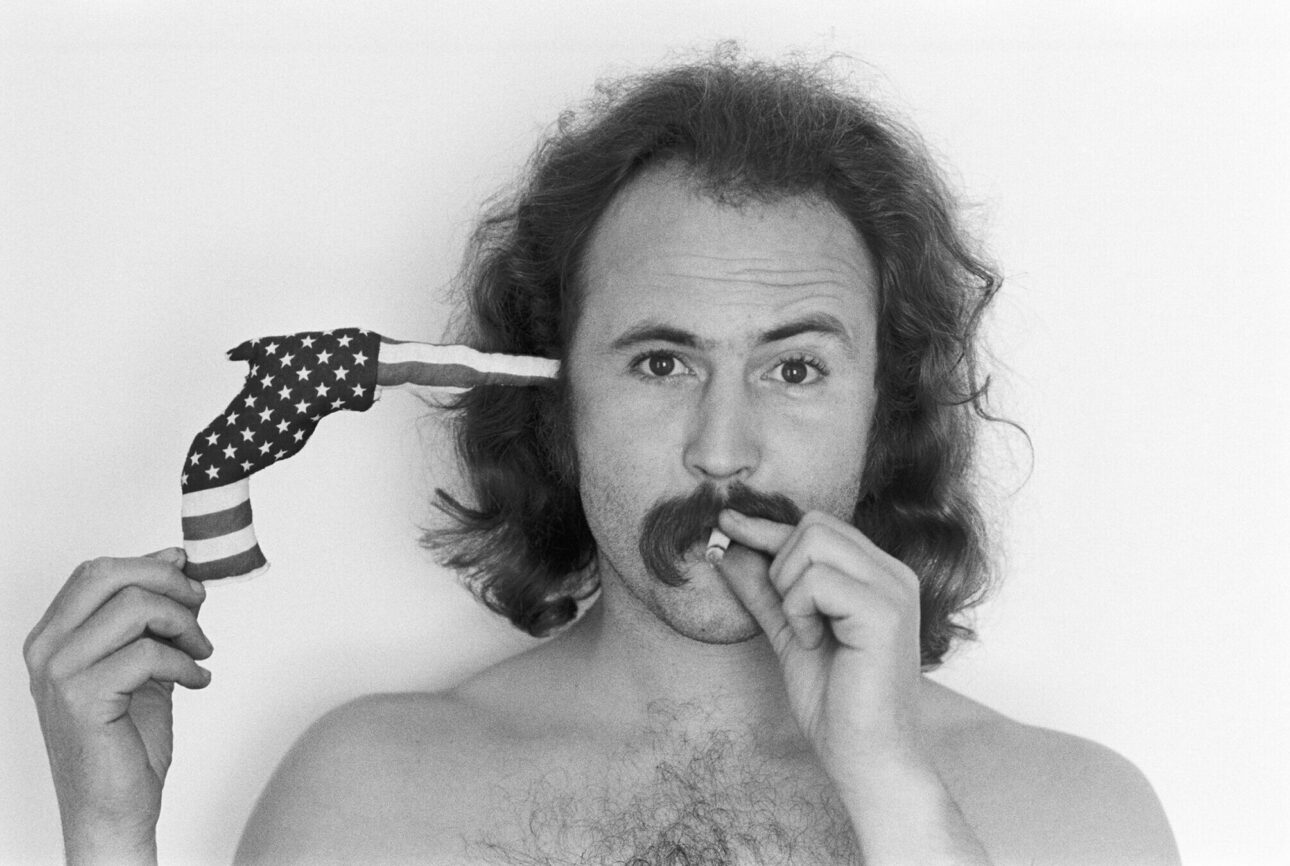

In 1970, when he was in a hotel room in Minneapolis with Crosby during a CSNY tour, Graham Nash opened the door and tossed a stuffed toy American flag gun, made for Crosby by a fan, onto the bed. Crosby, who was on a phone call with Bob Dylan and smoking a joint, immediately grabbed it and pointed it at his head, which was promptly captured on film by Diltz.

“In my opinion, that American flag gun shot is truly one of the most iconic rock and roll photographs ever taken,” A.J. Eaton, director of David Crosby: Remember My Name, says. “You see that photo and you get a chronicle of ‘70s Crosby – a rebellious character who was completely outspoken, sometimes to his detriment. And the fact that it was happenstantial and not manufactured by some art director somewhere makes it even more perfect.”

Ironically, despite Diltz’s talent and passion for taking pictures, he did not purposefully set out to be a photographer. “I never thought about taking pictures,” he says. “It wasn’t something I wanted to do.”

Born in Kansas City, Missouri on September 6, 1938 to a flight attendant and a pilot (“I was a TWA baby.”), Diltz was six years old when his father was killed in an airplane crash testing B-29s during World War II. After Diltz’s mother got remarried to a Navy officer who transitioned into the State Department, the family moved around a lot – at first, within the United States (Florida, Pennsylvania and New York), before heading overseas to Tokyo, Bangkok and Munich, where Diltz went to college, majoring in psychology.

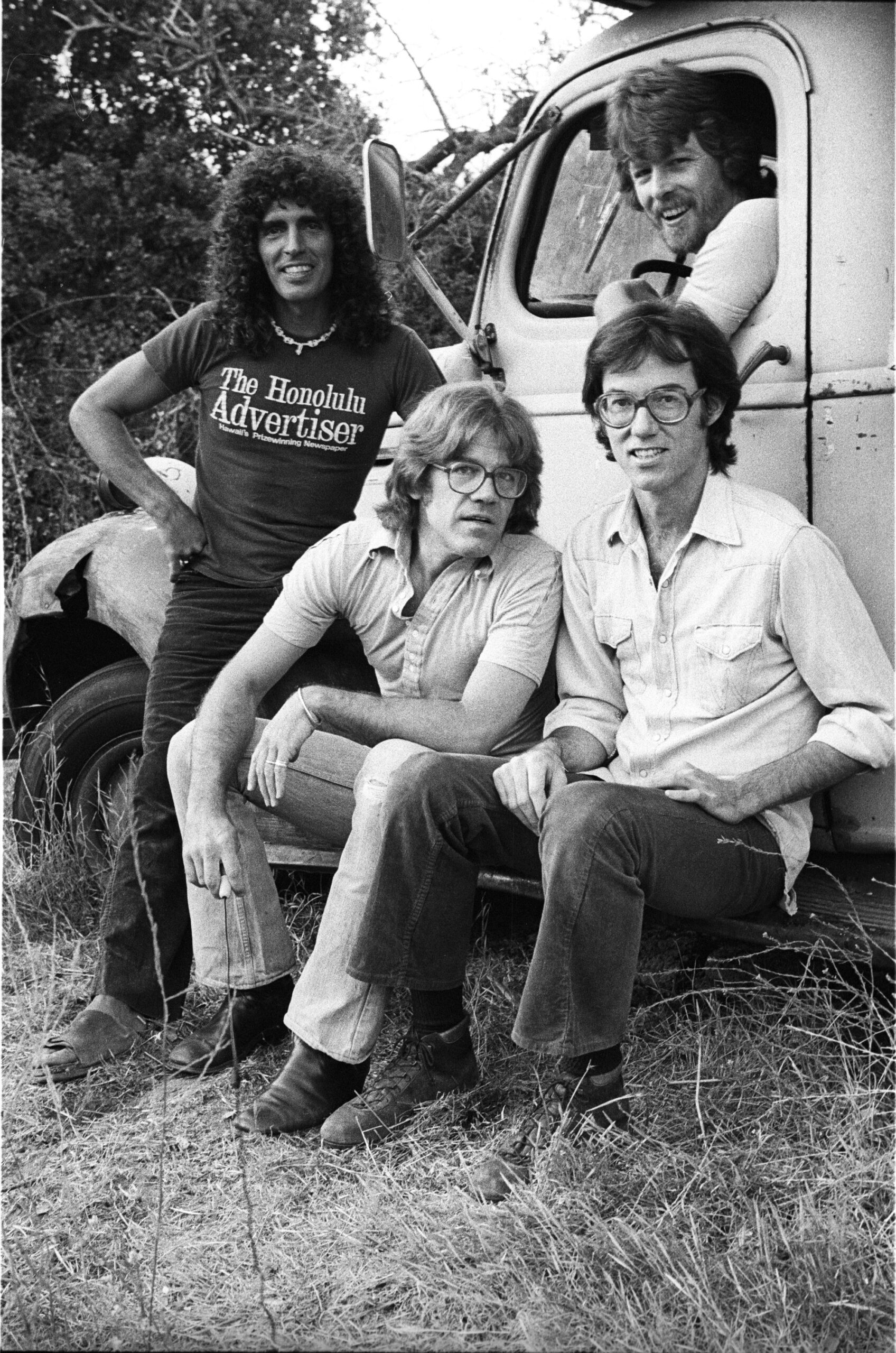

Next, he attended West Point military academy, which is when he fell in love with the music of Pete Seeger. A year later, he continued his psychology studies at the University of Hawaii in Honolulu, studying by day and performing folk songs at local coffee houses at night, singing and playing banjo. From there, he formed a couple of music groups, culminating in a four-part harmony quartet, The Lexington Four, who had a steady gig at a Waikiki steakhouse.

In 1963, after changing their name to the Modern Folk Quartet, the band decided to try their luck in Los Angeles. Shortly after their arrival, they captivated a crowd at an open mic night at famed West Hollywood venue the Troubadour. “The whole audience stood up clapping. When I say this, I get goose pimples,” Diltz says incredulously. “Like, wow, right when we hit the chorus, which had a four-part harmony, we got a standing ovation! It was uncanny and it was very powerful.”

Soon after, they signed a record deal with Warner Brothers and released two records, followed by a couple of singles on Dunhill Records. Inspired by The Beatles’ legendary appearances on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1964, the Modern Folk Quartet added a drummer and went electric (with a fifth band member added to the group, they referred to themselves as MFQ), leading to a collaboration with infamous record producer Phil Spector, who was looking to produce a folk rock band.

Diltz and his bandmates spent a summer jamming at Spector’s house several times a week. When Spector asked MFQ to record a cover of Harry Nilsson’s “This Could be the Night,” they thought they were destined for stardom when, on their second day at the recording studio, they spotted The Beach Boys’ Brian Wilson listening to playbacks of the song over and over in the control room.

“We were in awe of him,” Diltz says. “We thought, ‘We made it.’ The song was going to change our lives.”

The band waited and waited for the song to come out, but it wasn’t released until years later in England on a Phil Spector-produced compilation album. By that time, Diltz’s band had already broken up. (They’ve reunited several times since.)

Though they did not achieve the success they hoped for, MFQ paved Diltz’s ultimate path fortuitously when, during a tour in 1966, he and his bandmates stopped at a second-hand shop in Lansing, Michigan, where they impulsively purchased a few cameras, before heading to a drugstore to purchase film. The band spent their last two weeks on the road taking photos of each other.

“I never thought about what it was going to look like. It never even occurred to me to think about it,” Diltz says. “I was just looking in there [the camera], framing things and clicking. It was kind of a fun thing. When I got home after the tour and developed the film, I was amazed to see these little transparencies.”

For fun, Diltz staged a slideshow for his friends, which is when he was bitten by the photography bug. “When I saw the first slide glowing in the dark on the wall, I said, ‘Wow this is amazing.’ That’s when it [photography] got me.”

Diltz began hosting monthly slideshows, constantly keeping his eyes peeled for interesting things to photograph. “I was always looking for something colorful, something weird to take a picture of, maybe a bug up close,” he says. “I would try to get something with an impact to startle my stoned hippie friends – my best friends, my karmic friends, my tribe – who were my audience.”

“Friends would shout out cheeky titles to the slides,” he continues. “One time, at Mama Cass’s house, Pete Townshend and Keith Moon were there and they were trying to outdo each other thinking of funny things to say about every picture! (laughs)”

Though he loved entertaining friends with his photos, Diltz didn’t conceive of himself as a photographer yet, let alone a professional. However, a casual invitation from Stephen Stills unexpectedly set the stage for Diltz’s career. One day, when he was walking through Laurel Canyon, he heard the sound of a guitar coming out of a house. He walked up to the door and was greeted by Stephen Stills, who was visiting a friend and playing music. (Diltz originally met Stills in New York City when Stills attended a Modern Folk Quartet gig in 1964.) Stills asked Diltz if he wanted to accompany Buffalo Springfield to Redondo Beach, where they were doing a soundcheck at a folk club later that afternoon. Diltz went along, but only because he wanted to go to the beach to take some photos for his slideshows.

“I didn’t shoot the Buffalo Springfield at soundcheck, because I wasn’t a music photographer and the inside of the club was probably dark anyway,” Diltz says. “I went to the beach and took pictures of people laying in the sun and I got a picture of a guy with a monkey on his shoulder that became one of my favorite shots.”

When Diltz returned to the club 45 minutes later, a colorful mural on the back of the building caught his eye. He was just about to snap a shot when Buffalo Springfield walked out the back door of the club. Diltz figured he could use the band as a prop to convey the mural’s size, so he asked the band to lean against the mural and took some pictures.

Out of the blue a week later, a Teen Set magazine editor called Diltz and offered to pay $100 for one of his Buffalo Springfield photos. “I went, ‘Wow!’ No one had ever paid me a nickel for a photo,” Diltz says.

With his professional career underway, Diltz started attracting high profile photography work almost immediately. A phone call from The Lovin’ Spoonful’s record producer not only sent Diltz to New York to photograph the band and shoot their summer tour, but also resulted in his first album cover, Hums of The Lovin’ Spoonful. Shortly after Diltz returned to L.A., an editor at Tiger Beat magazine paid him $300 to shoot photos on the set of The Monkees television show, which evolved into Diltz becoming The Monkees’ photographer. A few years later, the same editor sent Diltz to the set of The Partridge Family, where he took photos and became fast friends with David Cassidy, with whom he traveled the world for a year taking pictures.

In accordance with his self-effacing demeanor, Diltz refers to his career as a series of “accidents” instead of attributing it to his talent. Still, he believes photography was fated. “I do think we come down here with some kind of a plan, some kind of a purpose, because I think we live many lifetimes,” he says.

“I think it [photography] is what I am meant to do,” he continues. “Since I’ve spent 55 years taking pictures of all of my friends who are musicians, it’s a thing. I can see that. (laughs) I didn’t remember that my assignment was to get a camera and take pictures, but it happened. Sometimes, I think, sure, maybe my guardian angels could have said, ‘We know Henry’s got to get a camera, so we’ll have him pull into this second-hand store.’ (laughs). I don’t know…but it sure as hell happened and it was a major moment.”

He paraphrases author Tosha Silver’s book Outrageously Open: “There is a divine plan unless you fuck it up. Try to figure out what the divine plan is, what the universe wants, and do that and don’t fight it.”

It certainly seemed like destiny when Diltz crossed paths with Gary Burden at a gathering of hippies in Griffith Park in 1968. Looking for a photographer to shoot an album cover for Cass Eliot, Burden, an architect who was working on Elliot’s house, approached Diltz. As it turned out, Diltz already knew Elliot and accepted the gig. That photo shoot, with Burden as art director, sparked an eight year photography collaboration during which the pair did publicity stills and 100 album covers.

Diltz says Burden was a good foil for his photography because he was an interesting conversationalist who engaged musicians in discussions while Diltz quietly took pictures, yielding some of his most celebrated photos.

When he and Burden went to Joni Mitchell’s house (the inspiration for CSNY’s “Our House”) to shoot publicity stills in 1970, she was leaning against the window sill when they arrived. Burden immediately started talking to Mitchell as they walked up to the house, with Diltz snapping photos the entire time. “I took all of these beautiful shots of her in the window,” he says. “I took maybe a whole roll of her while Gary was talking.”

The pair also took bands on adventures in order to shoot unique photos away from musicians’ everyday lives, interference from band managers, and studios. “We’d get them away from everything,” Diltz says. “And Gary would always say to me, ‘Just shoot everything that happens. Film is the cheapest part,’ and he didn’t have to say that, because I always photographed everything anyway. I would always just keep shooting.”

Not only did Diltz keep his camera in his hand at all times but, occasionally, he used two cameras at once, like when he shot the Eagles’ Desperado album cover in 1972 at Western Town at the Paramount Ranch (which was devastated by the Woolsey Fire in 2018) in Agoura Hills.

“We devised a little plan that the four of them would be backing out of a bank with their roadies across the street like a posse, and they would have a shootout and all the Eagles would fall dead on the street,” Diltz says. “I took photos with a Nikon Motor Drive in one hand and I had a Super 8 movie camera in the other hand, and I filmed a movie of them. They show it sometimes at their concerts.”

At other times, Diltz’s nimble fingers worked especially well on the fly, allowing him to work quickly, which was particularly useful for The Doors’ stealth Morrison Hotel album cover shoot in 1969 in downtown Los Angeles, where the man who was working at the front desk expressly forbade them from taking photos inside the hotel. When he stepped away from the front desk moments later, however, Diltz and the band snuck into the lobby, shot a roll of film and ended up with an iconic album cover.

“Henry Diltz has always had the knack for being in the right place at the right time,” Robby Krieger, The Doors co-founder and guitarist, says. “Like we were, in The Doors, when we wrote our songs. We had a knack for the right place at the right time. He managed to get some of the most iconic pics of The Doors. Whether it was Venice Beach, the original Hard Rock Cafe or the Morrison Hotel. We had a great time with Henry. He always made us smile.”

According to Diltz, Burden had a natural flair for choosing album cover photos. “Gary was so good at picking out the one that worked,” he says, “He was uncanny, sometimes staying up all night looking at 500 photos and saying, ‘This is the one.’”

He also credits Burden with giving thoughtful guidance during their photo shoots, sometimes steering Diltz away from close-ups. “With CSN, I was right up close filling the frame with the couch, which was rectangular, so with a horizontal frame it looked perfect,” Diltz says, “But Gary said, ‘Back up, back up, I want you to get the whole house in the picture,’ which I wouldn’t have done, but he had something in mind.”

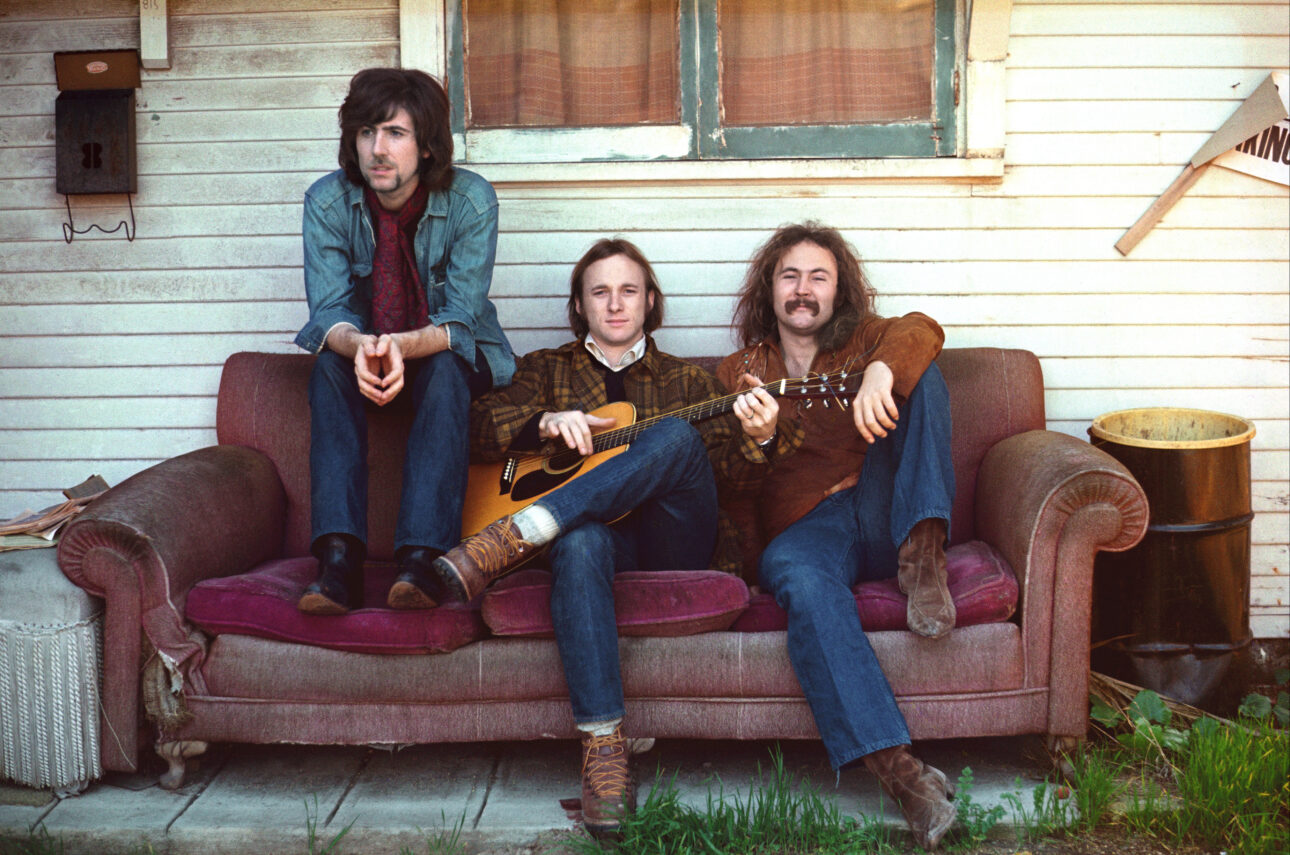

The Crosby, Stills & Nash album cover in 1969 was originally intended to be a publicity shot. Burden and Diltz were hired to take some publicity photos when Crosby, Stills and Nash, who did not have a band name yet, were still recording their first album. After taking some pictures in Burden’s garage and his backyard, they hopped into Burden’s station wagon and drove around West Hollywood, where they found an old house that had a couch outside of it.

Diltz snapped photos of the band sitting on the couch, with Nash sitting on the left, Stills in the middle, and Crosby on the right. When Burden and Diltz presented a slideshow of the publicity shots they had taken of the band, everyone thought the couch photo would actually make a great album cover instead. By then, however, the band had chosen a band name, but Crosby, Stills & Nash didn’t match the order in which they were sitting on the couch in the photo.

“It was like, ‘Oh shit, we just named ourselves Crosby, Stills & Nash.’” Diltz says. “So I said, ‘Let’s just go back! Jump on the couch in the right order and it will take five minutes.’ So we went back, but the house was gone. It was bulldozed down.”

Crosby, Stills & Nash used the photo for the album cover anyway.

A gifted storyteller, Diltz relays anecdotes animatedly and in vivid detail. Given their cultural significance, it’s almost impossible to grasp that this was his actual life, unfolding one day at a time. For example, when he arrived on Woodstock’s grounds two weeks before the legendary three-day music festival began, the stage was still being built. At that moment, no one, including Diltz, could have anticipated the magnitude of what was to come.

“I was hung up photographing the carpenters and all of that stuff…so it was almost surprising when the people showed up,” he says. “On Saturday morning, someone brought a copy of the New York Times and there was an aerial photo on the front page showing the surrounding countryside, and then we heard all of the freeways were closed, and we went, ‘Wow!’ That’s when we knew it was huge. Otherwise, it was just a hell of a concert!”

Staring at a photo he took of Janis Joplin looking exuberant onstage at Woodstock, Diltz smiles and says, “Radiant, right?”

Overall, Diltz estimates that he has taken “a million photos, give or take a few hundred thousand.” With his vast photo archive and friends who would encourage him to sell his photos, it was inevitable that Diltz would start his own photography gallery.

In 2002, he and his partners, Peter Blachely and Rich Horowitz, opened the Morrison Hotel Gallery in New York City in SoHo, followed by a Los Angeles location at the storied Sunset Marquis hotel in West Hollywood 10 years later, and a branch in Maui, where Mick Fleetwood is also a partner, in 2016. Currently, the Morrison Hotel Gallery represents over 100 photographers, including Timothy White, who became a partner in the gallery 10 years ago.

Whenever Diltz is at the gallery, patrons ask him to take their photos with their cell phones. After all, who would not want a portrait shot by Diltz? Given the era in which he forged his career, however one might assume that Diltz is a film snob who would frown upon photos taken with cell phones and digital cameras, however, he actually favors the latter which, he concedes, he originally resisted.

“In ‘05, I was saying, ‘I will never go digital. I am a film guy. I want those slides,’” Diltz says. “Then I picked up my friend’s Canon and I said, ‘Oh shit, this is focusing itself!’ You don’t have to set anything. You just pick it up and push the button and it will come out perfect. That blew my mind.”

He points to his digital pocket camera that is sitting on the table in front of him and says he takes upwards of 100 photos a day. “Trucks, graffiti, stars, hearts, tattoos, signs, animals…I have around 50 or 60 categories,” Diltz says. “I can’t walk down the street without taking photos. I’m in love with everything I see.” He plans to publish his photos in coffee table books.

Currently, he is working on Love The One You’re With, a forthcoming limited edition coffee table book about CSNY, featuring 1,000 of Diltz’s photos and assorted entries from the copious journals he has kept since 1968. In light of Crosby’s recent death, Diltz says the book feels like a tribute.

Reflecting on Crosby, Diltz speaks fondly. “I found him delightful,” he says. “He was very unexpected. He’d always make you laugh. Even though he had a crusty demeanor, he was a lovely guy inside…a lot of that music had to come out of a guy that was full of love.”

“When you get to be my age, many of your dear karmic friends have gone to the other side,” Diltz continues. “He is in an amazing place and I’ll see him over there. I know I will. I do believe we go someplace and it’s amazing, a kind of paradise where you learn so many things and understand so many things. You study over there for a while and then you come down again for another try to continue the progression.”

As to what keeps the lively Diltz so youthful at 84, he laughs and says, “I never grew up. I feel very childlike. I feel very young. Innocent.”

Certainly, Diltz’s inquisitive and active mind contributes to his vitality. A well-read, lifelong spiritual searcher, Diltz fell in love with Paramahansa Yogananda’s book Autobiography of a Yogi in the mid-’60s and says Søren Kierkegaard’s existentialism has stuck with him since college. Recently, he read The Untethered Soul: The Journey Beyond Yourself by Michael Singer.

He is also a fan of Coast to Coast AM, a late night radio talk show that he often listens to until the wee hours of the morning, fascinated by host George Noory’s multitude of guests, including psychics, energy healers, astrologers, and numerologists, from whom Diltz says he learns a lot about human behavior.

“I’m more curious now than I was before, even when I studied psychology in college,” he says. “I just had this thought when I was looking around an airport —There are hundreds of people walking by and every single face is the center of a universe. Their life, right? Their hopes, their fears, their dreams, their secrets, their life plan, their history…all that’s in your head is in their heads, too.”

“I found out a couple of years ago that my Chinese animal is a tiger and tigers like to hide in the bushes and watch the other animals, so that explains why I’m an observer,” Diltz notes, before stating his personal ethos succinctly: “My thing is just, ‘Watch life. Take pictures.’”