I can always tell an Amina Cruz photograph by the way her subjects look like the most beautiful and most powerful people I have ever seen, framed dynamically in moments of tactile presence rather than a passive act of removed documentation. Whether they’re on stage, in the crowd, or sitting for the camera, they look like friends, neighbors, family, and lovers, respected and known, because for Cruz they often are. Cruz’s photographs are utopias and landscapes filled with conversations, power, relationships, memories, music, joy, and fantasies that you can feel.

“The reason I was so drawn to photography in the beginning, is it was safe to navigate my emotions,” Cruz declares, thinking back to her youth spent bouncing between East LA and Tampa, Florida when she started shooting as a shy 14 year old on a family members’ film camera. “It was safe to be like, oh, I’m sad or I’m scared, and I still do that.” When Cruz first went to sCum, the East LA queer punk nightclub where she shot many iconic portraits of the crowds and queens alike, she still felt antisocial and anxious. “I knew how to navigate that world with my camera.”

The first time she saw punks was also in East LA, as a child outside her cousin’s home in Boyle Heights. She remembers them to this day: one sitting on a curb in a leather jacket, mohawk-clad, legs asymmetrically straddling the curb, another standing, turned at an angle talking to him, outside of a gig at a now iconic punk rock club called The Vex. “I was like, this is amazing, this is where I want to be. I remember going home and fantasizing that I was there talking to them outside and I had my little outfit on.”

When I hear the photographic way she describes this pivotal moment of really seeing these punks that helped her also see herself, it reminds me of Cruz’s work, and the way it resonates with so many people, especially queer people of color and queer punks, whom Cruz has spent the last decade making beautiful portraits with.

“Photographing is an exchange of trust” Amina Cruz says to me, shifting between images of queer Brown and Black punks. They are often showing off looks at backyard drag shows, dancing against mirrored walls in small clubs, posing in soft bedrooms, and lounging on farms and in gardens, decked out in dangling earrings, steel chains, lace crop tops, and leather hoods.

The photographs that first moved Amina were news and war photos that she saw in newspapers and books from her school library. The 1972 photo of a young girl in a tub being held by her mother, titled “Tomoko in Her Bath” shot by W. Eugene Smith in Minamata, Japan, would move Cruz to tears. She had a photograph taped up in her childhood bedroom of a protestor blocking a line of military tanks in Tiananmen Square. Cruz used to want to be a war photographer until she learned that war photographers had to stay neutral in the face of violence.

Music magazines became a saving grace and were Cruz’s first exposure to portrait work, introducing her to artists like Kim Deal and Bauhaus, which led her down a rabbit hole to other artists and movements. When her mom would go to the market, Cruz immersed herself in magazine racks looking at everything she could get her hands on. Moving constantly, she had to make new friends every year, so libraries, music, and magazines were a constant companion and source of inspiration. Photography became her tool of navigation, the most consistent thing in her life.

“The only thing around that I could identify with was punk,” Cruz remembers, reflecting on how it was a pivotal part of her coming of age. As a kid she was very aware of racism and classism. “My grandpa would pick me up at Catholic School in South Pasadena after his shift and we would drive back to East LA, so I saw every day the shift of the neighborhoods, the class disparity. Then I spent my teen years in Florida which was really racist, a dude would literally wear a Youth of the KKK shirt to school and nobody would say anything to him. I was angry. Punk was the only thing that was like, ‘you can fuck shit up over here and we’ll like it.’ It leaves you with this feeling of “I am going into a fucked-up world,” But you know, I think punk allows you to navigate that. It did for me. And that never left.”

Transgression has always been a big part of her style.

“When everything is saying ‘no,’ or ‘you’re wrong,’ or you’re bad like the super strict Catholic School I attended, it was always no to all the things I wanted to do,” Cruz remembers, adding that part of why she loves photographing queerness and community is all very connected. “The details, the consideration. That one dangling item on the nail was very, very considered. Using a rosary as a necklace meant everything in the world to me as a teen and I had to fight. I came up at a time when you would be called a freak, and got beat up. So all of the signifiers are important. I love that we literally build the world that we want to live in. That’s 100% true in queer culture. And I feel like we build ourselves. That’s where transgression comes in. Despite everything saying that we’re wrong or telling us no or threatening death – we’re still gonna do it.”

Both Amina’s style and her subjects have their own point of view and their own voices. Whether her subjects are sharing an intimate sweaty make-out session in the back of a Mexico City discoteca, or dancing mid thrash to a beat you can feel by seeing the gestures of the crowd moving like a wave in time made discernable by flying fringe and eye contact, or sitting with their faces turned away from the camera, in Cruz’s visual world the people in her photographs hold power.

She shows me a black and white photograph of a person looking away, their head recently tattooed with a pair of handcuffs in the shape of hearts, reminiscent of BDSM cuffs you might find in a domme’s bag, complete with a shimmer mark from the artist, the shine of Cruz’s flash bouncing off illuminated Christmas lights, and the glow of a LA backyard drag show. Most portraits center on a subject’s eyes, this one centers the cuffs, and also the Ojo necklace around the subject’s neck.

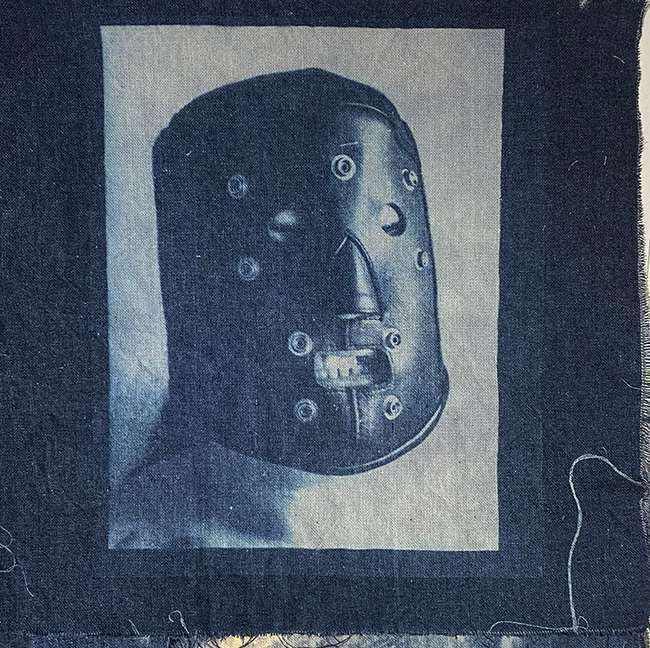

Cruz’s work is often accompanied by ritual. The ritual of the intentionality of putting oneself together, of consideration, of seeing and being seen by queer punk and Brown aesthetic practices. As of late Cruz has become obsessed with alternative photography, mixing chemicals applied at times with brush strokes, developing photos on drop cloth and ceramic pieces and even plaster, the results of which bring a different kind of depth and physicality of artist participation than traditional prints on photo paper.

She shows me a new work that juxtaposes a self-portrait hand printed onto cloth with a beautiful full-color print of a Eucalyptus tree that is an icon in its own right in Boyle Heights. She was able to take its picture just months before the recent storms in Los Angeles caused it to fall.

“I’m in there” she says, as we talk about using drop cloths with the deep denim tone of cyanotype to nod to both dyke and working-class history, and mixing sediments from the grape farm her grandparents worked on in the 1950s to create a pigment layered with history and power from Brown migrant laborers who have spent decades on the land, “I’m putting my hand in there. It’s important for me to always have a nod to the working class. We know how to work, but it’s going to kill us.”

Cruz pivots and shows me a photograph that is unlike any of her other work. A concrete structure stands defiantly in the middle of a dirt field in an Arvin, California vineyard during sunrise. In the middle of graffiti that mirrors the purple and orange energy of the Central California skyline it’s nestled within is a wheat-pasted black-and-white print of a young man in a work jacket, dark brown hair swooping over his adolescent face.

“He looks so innocent, but also a little tough,” Cruz says, “I can’t get over his eyes, they look scared and willing at the same time. The way he gazes directly into the lens blows me away.”

This is Amina’s uncle. The image is from an ongoing series, me & mine & you & yours, in which Cruz has been honoring and spending time with her families’ roots, reproducing photographs from the 1930s to the 1970s, breaking into the farmland where her grandparents met and family worked, and installing images and power objects onto the very structures and pieces of Earth that once held her ancestors. Over the last two years Cruz has pasted up images like one of her great grandmother near the site she once worked, her grandparents as a young family near where their home once was, and even constructed unfired clay reproductions of old grape boxes to represent her Nana who hated working in the fields and at 15 worked in the packing house instead.

“It was important that I do this in the middle of the night because I wanted the sun to rise on these images to activate them,” Cruz tells me, “I want to show my ancestors that I see them, that I still think of them. Not just my ancestors, but other people still working this land.”

Wheat pasting art in public spaces that she is connected to that every day people have access to is a way for Cruz to comment on and bust out of the rigid, racist and classist gallery system, paying homage to her family and making art accessible to everyone. “I can make as much work as I want about my Nana and my grandpa working in the fields, but they were never gonna go to the gallery, that’s not their world,” Cruz says, “my family feels uncomfortable in those spaces.”

Over the last few years Cruz has been able to let herself explore, something she attributes to getting into graduate school at UCLA.

To Cruz, the most radical thing is when everyone is involved.

“What desire it takes to live this life, the journey of being true and finding yourself when everything around you is telling you ‘no.’ For me, I take that into consideration, when I photograph not just queer spaces, but anyone.”