“Most people get ill for a week after the tour ends,” says David Rhodes, Peter Gabriel’s longtime guitarist. Rhodes has been a vital element in Gabriel’s studio and touring work since 1980, and his style and range have attracted Kate Bush, Japan, and many others. He has also recorded with Paul McCartney, Roy Orbison, Tori Amos, and Toni Childs.

When Rhodes climbed onstage with Kate Bush, it was for agonizingly long-awaited concerts that fans had been dreaming of ever since Bush abandoned live performance in 1979 at the end of her debut tour. Preparations for the 2014 comeback shows were “very intense,” Rhodes says, demanding both choreography and improvisation. “Everyone was very nervous.”

Rhodes is one of a range of musicians talking to SPIN about the pressures and destabilizing weirdness of live performance, and ways to handle its sometimes punishing forces.

Gabriel has an internal switch, Rhodes says during a break from tending to his bees in wuthering Dartmoor. “With Peter, you can be in casual conversation about almost anything at the bottom of the stairs to the stage. As soon as he’s on the steps and he ascends, there’s a change in demeanor. He’s on.”

I ask about the strangeness of the artificial environment they occupy onstage. “I learned from my friend Peter Hammill [of Van der Graaf Generator] that stage time is the one sacred part of the day. It’s the one time of day when you know what will happen. It’s a great relief when you play that first chord,” Rhodes says.

And playing the last?

Even after a grueling tour, the downtime can offer less relief than expected. As Rhodes has said, musicians often fall sick in the aftermath. Plus, various kinks and quirks in their body-clocks and muscle memories can be slow to dissipate. “Every evening, for a week or two, you get twitchy at showtime,” says Rhodes.

Musicians grapple with this body-shock aftermath in a range of ways, some healthier than others and some more austere than others. Jazz drummer Michael Zerang (Mats Gustafsson) is conscious of the post-tour malaise and clear about how he needs to face it: “Long tours are often followed by long periods of near isolation. When I return home, I need to recharge my body and to whatever extent possible, assimilate all that I have learned and done.”

But the hazards of touring go beyond exhaustion and spotlight withdrawal. Dangers also stem from the prolonged, necessary adoption of a stage persona.

Taking that place under lights and above expectant and demanding audiences waiting for you — your chords, your rhythms, your magnificent chaos — to elevate them out of normal life and into transcendence, is not a role for ‘normal’ people. Musicians must first transform themselves.

David Pajo (guitarslinger with Gang of Four, Slint, and Yeah Yeah Yeahs) says, “There’s a certain amount of ego involved, to want to go onstage, even if, like me, you have severe stage fright. Most musicians have a ‘live persona’ that they can turn on and off.”

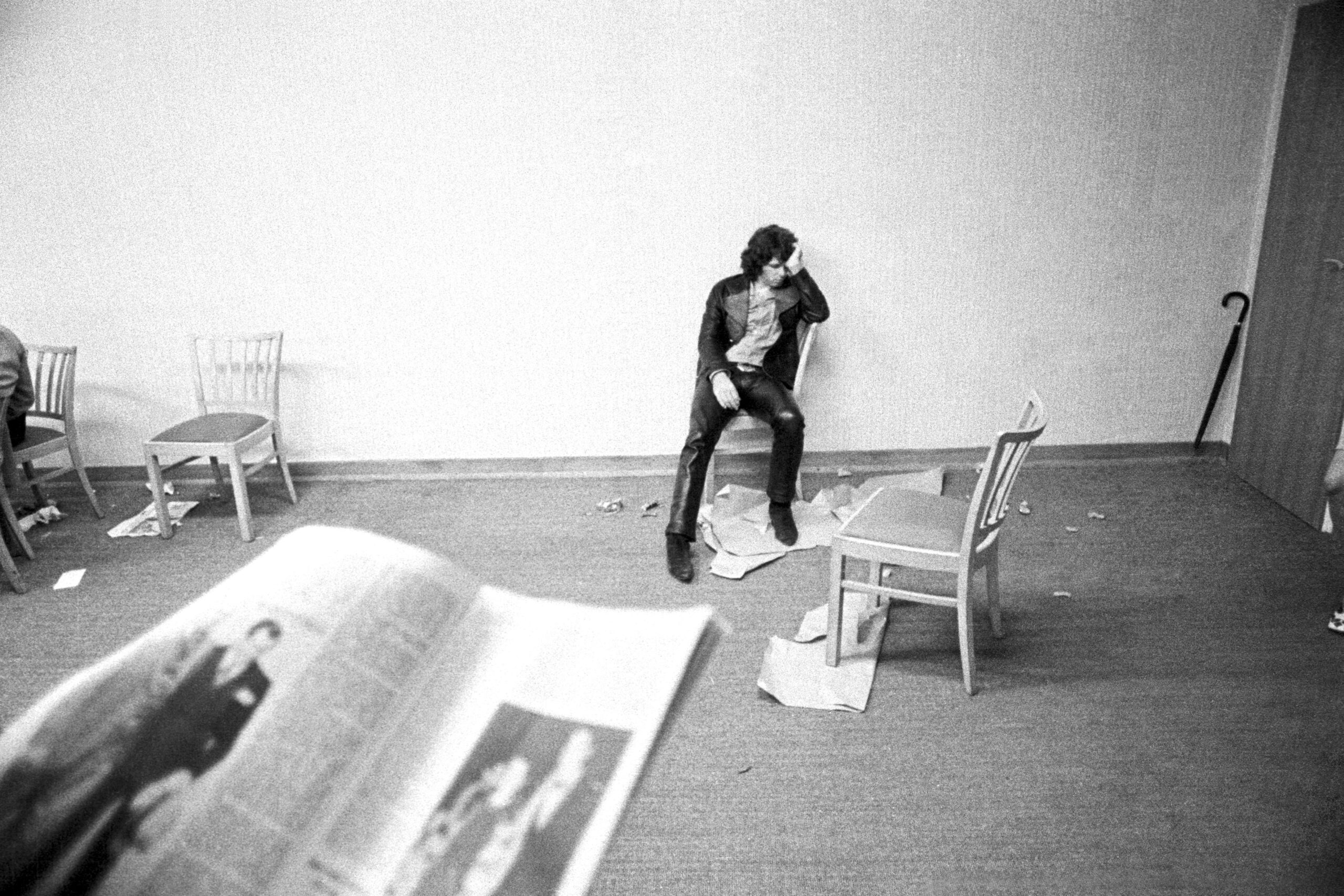

But when the switch is broken, and the persona stays on, what then? Psychologist Carl Jung warned of “inundation” of the ego by an archetype or personality complex. Performers, as Jim Morrison says, take “a face from the ancient gallery.”

These archetypes are well-worn, not least Dionysus torn apart by his delirious fanatics, the altered states of the shaman, the Faustian Robert Johnson bargaining with the Devil, the sympathetic Satan of Milton’s Paradise Lost upon whom all rock depends, the sacrificial Scapegoat of rock and roll suicide … You know the types.

And as I write, it is Syd Barrett’s 77th birthday, and Robyn Hitchcock (The Soft Boys) has just posted a moving tribute to the fallen idol and shamanic hero of the early Pink Floyd, who died in 2006. Syd Barrett’s psychosis haunts the band, whose music never slips far from the vicissitudes of the psyche, the dramas of the ego.

Remain in the music game long enough or at a certain pitch of fame, and you begin to write about its ruthlessness: “Come in here, dear boy, and have a cigar/You’re gonna go far.”

And about its casualties: “Remember when you were young?/You shone like the sun … Now there’s a look in your eyes/Like black holes in the sky.”

Artists who don’t collapse but whose personae outshine their real selves can be overwhelmed by a shadow of resentment and express it in cruelty.

Under Roger Waters, Pink Floyd’s The Wall tracked the decline of the dehumanized performer as messiah turned fascist: a psychic trajectory familiar to Kanye West.

“Weird scenes inside the gold mine,” sings Morrison.

The stage does strange things to people.

Anthropologist Arnold van Gennep describes three stages of ritual transition: preliminal separation, the liminal/threshold space of performance, and the post-liminal incorporation of the experience.

In other words, the performer first splits off and prepares to carry an audience of perhaps thousands, then enters the sonic temple and lets rip to the far limits of their abilities, but must step back into a world where the charge now carried is less useful than it is destabilizing, unless it can be integrated.

Hence, so many musicians are in crisis.

The Tour Health Research Initiative (THRIV) is a research group examining the hazards of touring to musicians and crew, and its survey results are stark.

Of 1,100 touring personnel surveyed in THRIV’s 2020 study, 34 percent of respondents suffered clinical depression; 70 percent experienced insomnia; 79 percent voiced significant financial concerns with 37 per cent “very strained”; 58 percent reported the loss of a colleague to suicide, and 26 percent confessed to suicidal ideation and actions themselves. Furthermore, 62 percent lacked any substantial plan for life after touring.

Clinical psychologist and THRIV co-founder Dr. Chayim Newman told SPIN that both artists and crew are prone to the “dehumanizing of people in this industry. Artists get lost because they’re deified and they sometimes forget who they are as humans, and crew members, on the other side, aren’t often treated as humans. They become faceless, and it’s just ‘do your job.’”

I ask Dr. Newman about the extent to which both artists and crew live with the burden of inherited archetypes.

“Completely, and totally,” says Dr. Newman. “And there’s an ethos that pervades all those archetypes which is ‘the show must go on.’ This essentially says: sacrifice whatever your own personal state of wellbeing is in order to get your job done.” Within this, there is some fear of treatment, he says. “I’ve had artists who, let’s say, might be bi-polar or suicidal, who tell me they don’t want to take medication because it will stunt their ability to write meaningful music.”

The best results, says Dr. Newman, of Amber Health, come from Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and mindfulness therapies. ACT allows musicians and crew to “access their emotions, but in a way that doesn’t cause havoc in their behaviors and in their relationships.”

Dr. Newman respects the concept of the stage being sacred and the fear of losing that edge. “All that exists up there is the music and really the connectedness — which is what mindfulness is,” he says. “Those are the ultimate moments of attunement for an artist, and it absolutely makes sense that is that sacred space.”

And touring, Newman says, can have “a really deleterious effect on people when they come home, and there really isn’t all that stimulation, all the social engagement, and all of the things that are so rich, exciting, and powerful … There’s a crash that we know happens, a real abrupt and jarring adjustment to coming home. And in the support groups we ran during the pandemic [the question] was, when the industry’s shut down, then who the hell am I?”

And the more the “I” is entangled with a performance persona, the more confusing things can get. Annie Gardiner (art-rock duo Hysterical Injury, French electro-pop band The Penelopes) says: “I understand that performers adopt a persona for various reasons, some more deliberately than others. I like Kate Bush’s exploration of that, and how the characters in her songs get explored through dance, movement, and dress — keeping in mind that she quit touring after her only tour!”

Grounded in the DIY scene, Gardiner avoids conventional music trappings in favor of transparency. “I haven’t deliberately ever employed a persona other than a choice of clothes — usually something I wear day-to-day anyway, and rarely wear makeup. That said, an audience can interpret that as a persona, and it could be an unconscious one. In early incarnations of Hysterical Injury, I did think about ‘how I would like to perform’ and did so by pushing myself to the edge of my energy, but I found myself embarrassed as it felt fake, ultimately, or at least a veil to the vitality you get from performing if you are fully present.”

Los Angeles post-punk artist Taleen Kali says that sensory deprivation helps her detach from the drama of the stage: “Finding a dark, quiet place really helps me.” She laughs, “I know that sounds so goth. It really does help to meditate and be with my thoughts for a while.” The contained space of clubs can have a beneficial effect, she says, contrasted with the sprawl of the city.

“I feel at home in venues and with the kindness of strangers who appreciate the music. I’m always sensitive to light and sound, so I think having a controlled environment of sonics — as opposed to sounds of urban chaos I’m used to in L.A. — can be really calming for me. When we tour up and down the Cali coast and PNW, we have less driving times, and it’s always so lovely to find respite in nature. One time we rehearsed in a park in Seattle. Went to the beach in Santa Barbara. And we found this park in Davis to roam around for a few hours. Honestly, it’s even amazing to stop by a record store, gear shop, thrift store, boutique, or bookstore. It feels really good to connect with the rhythm of each city, and since we don’t always have the chance to, it’s extra special and grounding when we do.”

Kali also employs ceremony to cultivate a sense of sacredness in performance. “On our 2022 tour, I definitely felt like I needed more rituals and grounding since it was our first time touring in three years, so I got a buncha crystals from a shop in Alameda in the Bay Area and set them up on my pedal board…If we’ve had a rough day and are feeling unhinged and divided, we do this group improv exercise that our bassist Miles showed us. It syncs everyone up with the same rhythm and eye contact.”

“You don’t stay sane,” says Hutch Harris of The Thermals, “and you shouldn’t try! You just have to give up any kind of sense of normal life. The effects on ego and identity are actually positive, at least on the surface. That is to say, if you’re having a good tour! … Now, if your tour is not going well, you feel the opposite: unloved and worthless. The longer you tour and play music professionally, the stronger your identity is tied to this lifestyle. I’ve definitely had a crisis of identity since I stopped touring and playing in bands, publicly. Like, who am I even? Freed from the highs and lows of touring life, I have struggled to find something else to determine my own value.”

The struggle to reintegrate into life offstage is the main show, according to Dr. Newman. “At the deepest levels, psychologically, that’s what we’re addressing,” he says. “The most similar thing to being on the touring side of the music industry is being a soldier in the military. There’s exhaustion and lack of sleep. There’s being far away from home. There’s stress and pressure in a profound way.”

Jessica Billey (the Mekons, Fergus Daly, says that after the magic of performing, coming home is definitely the hard part. “You have to remember how to reconnect with your stationary life. Touring can make you feel like you are outside of time. You are everywhere and nowhere at once. When you’re performing, you are gathering energy out of thin air.”

And then the comedown, or, in Neil Young’s coda to Jim Morrison, life after the gold rush.