It’s one of the great untold tales of American music: the nexus between Rock & Roll Hall of Fame inductees Lynyrd Skynyrd and the Allman Brothers Band, soul legend Otis Redding, and three visionary mavericks whose record company, Capricorn Records, helped break down racial barriers in the South and launch the musical and cultural phenomenon known as “Southern rock.”

Founded in Macon, Georgia, in 1969, Capricorn was the music label and recording studio behind the success of the Allmans, Marshall Tucker Band, Black Oak Arkansas, Dobie Gray, and many more artists that are now household names.

The origin story begins in the mid-’60s with brothers Phil and Alan Walden (as well as, for a brief time, their older brother Clark “Blue” Walden), who managed or promoted Otis Redding, Percy Sledge, Etta James, John Lee Hooker, Al Green, and Sam & Dave, and published songs such as “Respect,” “Soul Man,” “I Can’t Turn You Loose,” and “(Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay.”

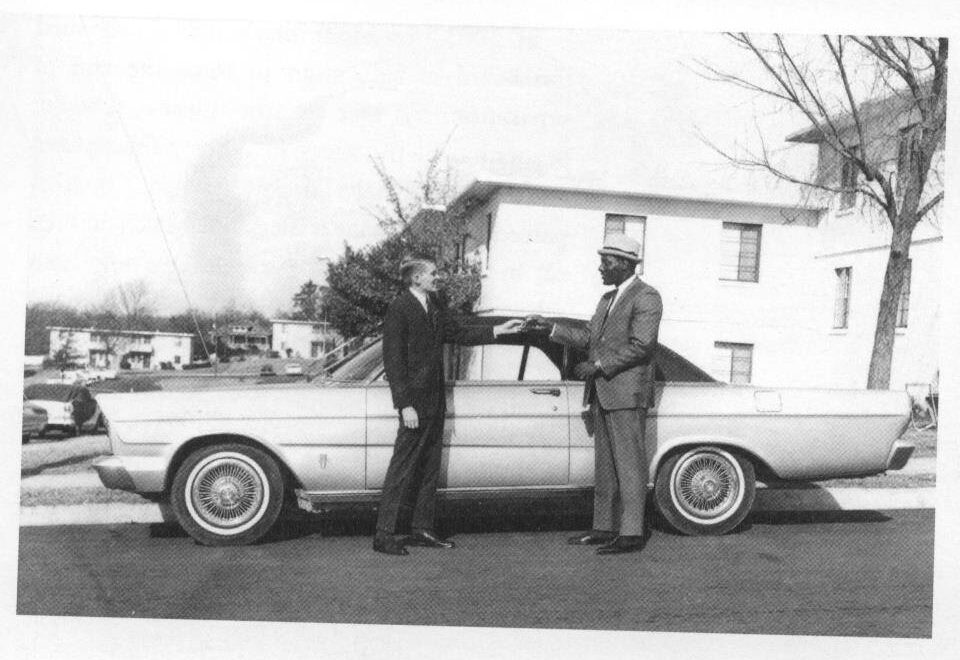

When Phil Walden met Redding in the late ‘50s, signing him to a management contract in 1958, Macon was segregated. Phil’s was often the only white face at black dance halls. When seen out and about together, the trio got abused and harassed by local “crackers” and rednecks. But Phil and Alan were not deterred. They did things their own way. President Jimmy Carter once said, “It was [the Waldens] who began to meld the white and black music industries.”

Redding became a close friend to Phil and Alan. At the time, it wasn’t the normal thing in the South for a white man to socialize with a black man, let alone manage him, let alone travel with him, let alone go into business together. But this Redding and the Waldens did with the creation of publishing company Redwal Music Inc, one of the first integrated companies in Macon. (The first three letters of their respective names formed “Redwal.’”) Redding’s death in a 1967 plane crash devastated the brothers.

Alan Walden, who co-wrote Redding’s song “Champagne and Wine,” told writer Michael Buffalo Smith in 2002: “The whole world stopped cold for me that day. My star and my best friend were gone. I had never known pain like that. He was the first man I loved outside of my immediate family. I still cry sometimes for Otis. My brother and I were crushed by this terrible accident but we were still determined to go on and on and on. Soul music died almost the same day as Otis. It began a very fast decline over the next year. We began to look at the rock and roll bands.”

And with that, Capricorn was born.

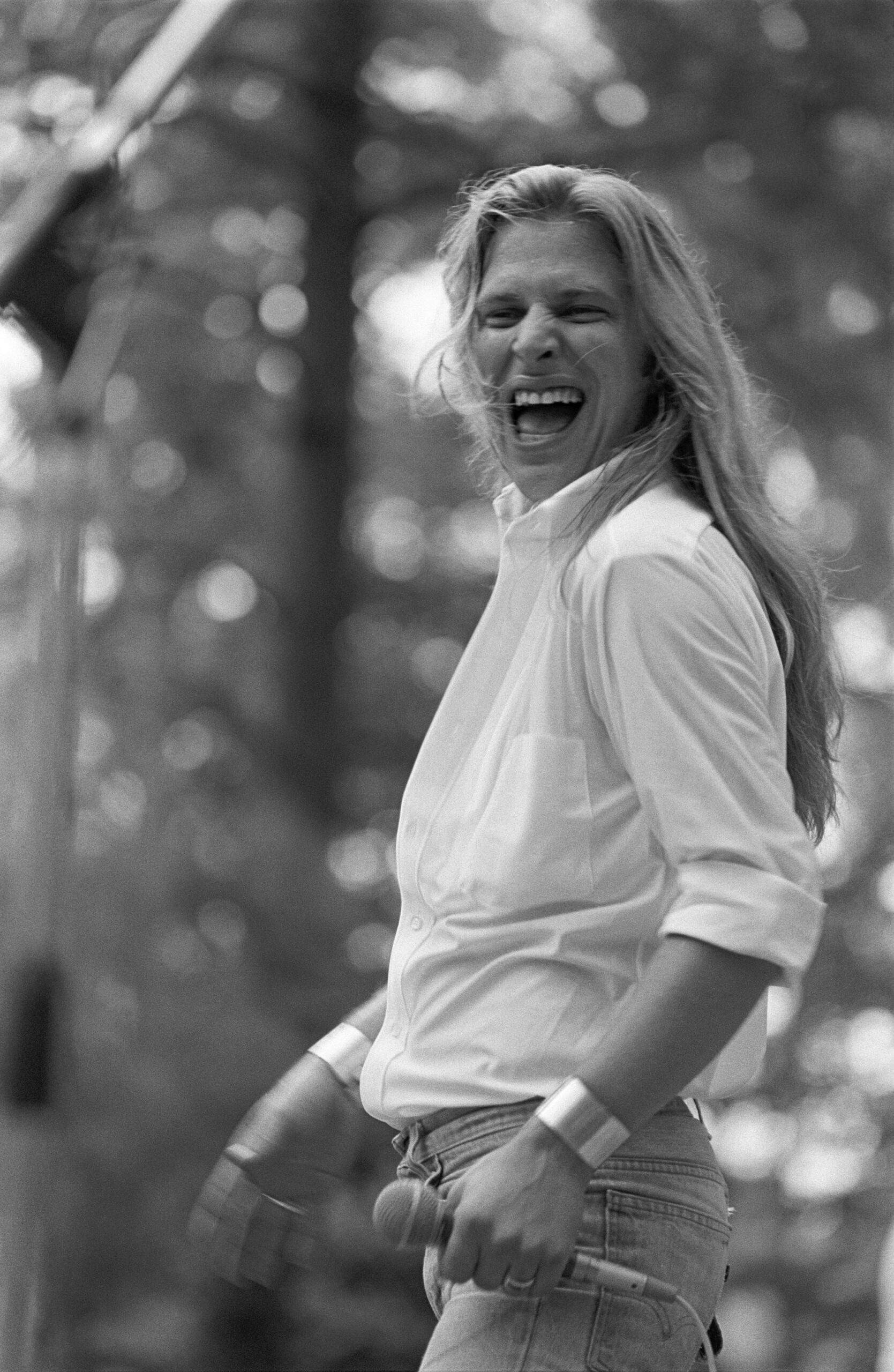

Any Walden brotherly unity after Redding’s death, however, was shortlived. Within a year Alan parted ways with Phil to start his own company, Hustlers Inc. and began auditioning bands. Out of 187 acts, he picked just one: a group out of Jacksonville, Florida, called Lynyrd Skynyrd.

Signed to his new company, Alan managed the future rock legends at the peak of their career and published the band’s best-known songs, “Freebird” and “Sweet Home Alabama,” which today stand as anthems of the South.

Skynyrd signed to MCA Records on the hood of Alan’s 1973 Ford pick-up truck in the parking lot of the Macon Coliseum. Alan co-wrote their single “Saturday Night Special.” Alan had an eye and ear for Southern rock bands: Later in the decade, he’d also manage Outlaws.

But Phil, who had his own knack for spotting talent (he signed a young Boz Scaggs to a management contract) didn’t want Skynyrd for Capricorn because he thought they sounded too much like another Jacksonville group he’d picked up for the label, the Allman Brothers Band. Phil had discovered lead guitarist Duane Allman after his incredible playing on Wilson Pickett’s cover of “Hey Jude” at FAME Recording Studios in Muscle Shoals, Alabama.

Duane would later duel guitars with Eric Clapton on Derek and the Dominos’ classic “Layla,” and the Allmans (minus Duane, who was killed in a 1971 motorcycle crash) would become the biggest band in America, making Capricorn Records the largest independent label in the country, if not globally. At its height, Capricorn was generating almost $200 million in record sales and its acts went platinum (million plus sales) 17 times over.

Albums released by the label included the Allmans’ Brothers and Sisters, At Fillmore East and Eat a Peach. Singles included the Allmans’ “Ramblin’ Man,” which went to No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100, and Elvin Bishop’s “Fooled Around and Fell in Love,” which went to No. 3. But Capricorn wasn’t just a Southern rock and country label: It had a healthy soul and R&B roster that included Percy Sledge. The likes of Charlie Daniels Band, James Brown, and, of course, Lynyrd Skynyrd, also recorded at its studios.

Phil Walden had a South African partner in Capricorn Records. His name was Frank Fenter, and he’d been handpicked by Atlantic Records heavyweights Nesuhi and Ahmet Ertegun to run Atlantic in Europe, in which position he was pivotal in signing Yes and Led Zeppelin to the label.

Fenter had met Phil in London in 1966 when Fenter arranged for Otis Redding to appear on the BBC’s Top of the Pops, and he joined up with Phil a year later when the pair took the “Hit the Road Stax” tour, featuring Redding, Booker T & the M.G.’s and Sam & Dave, to the continent.

The Ertegun brothers, trusting Fenter implicitly, agreed to finance Capricorn from New York. But Fenter was no stereotypical white racist South African. When Fenter came to Macon in 1969 with his Swedish baroness wife, Ulla “Kiki” von Blixen-Finecke, one of their first houseguests was Aretha Franklin and her husband, Ted. The couple slept over. The next day Fenter got a visit from the local sheriff, who told him that overnight stays by “people of color” were not encouraged. That advice was actively ignored.

When Phil and Fenter weren’t accepted into Southern blueblood country club Idle Hour, they found a welcoming venue for Capricorn staff and bands at another club called River North, founded in 1974.

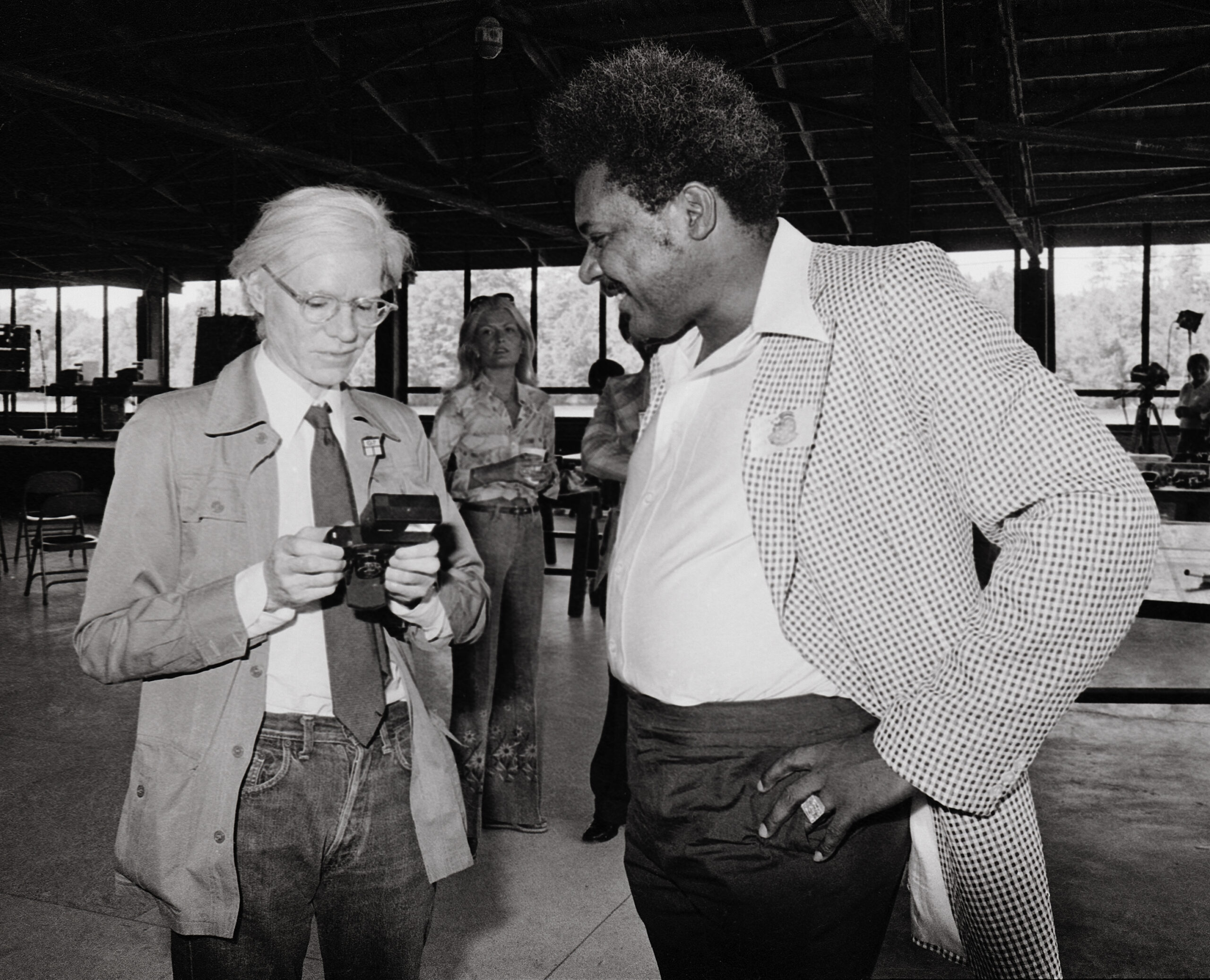

Capricorn made Georgia the place to be. The South was suddenly cool. In 1976 the BBC sent a film crew out from London to profile Capricorn for its music show The Old Grey Whistle Test. Governor of Georgia Jimmy Carter, who’d win the presidential election that year by defeating Gerald Ford, attended the Capricorn Barbeque & Summer Games event at Lake Sinclair, near Milledgeville, northeast of Macon. Andy Warhol, Mick Jagger, David Bowie, Richard Pryor, Cher, Bette Midler, and Don King were other guests at Capricorn’s annual barbeque.

As a major rival to established record companies on the east and west coasts, Capricorn was a huge part of the South’s ’70s cultural renaissance, and Hollywood caught on to the Southern buzz, making hit films such as Smokey and The Bandit (1977) and TV shows such as The Dukes of Hazzard (1979-’85).

But the glory days weren’t to last.

Capricorn went bust in October 1979 due to a combination of factors, not least the decline of Southern rock (the Lynyrd Skynyrd plane crash in Mississippi in October 1977 was an unmitigated disaster for the genre), the company being sued by the Allman Brothers for unpaid royalties, mounting debts to then-label overseer PolyGram, and, most of all, Phil Walden’s alcohol and cocaine addiction.

Phil admitted he was driven to the brink of suicide: “I was embarrassed … the guy who could make no mistakes was just about to blow his brains out.”

Recalled Dick Wooley, former Capricorn vice-president of promotions, in Kiki Lee’s biography of Wooley, Promotion Man: “Drugs played an important role in the ’70s music culture. It was in the recording studio, in the office and in our social life; it was as essential as gin in a martini … the price of success exacted an especially heavy toll on Phil … with the success of Capricorn his problems were raging out of his control; it manifested in embarrassing public tantrums that kept his lawyers busy putting out fires and it keep everyone in the office on edge. Phil’s infamous temper outbursts were becoming more frequent and explosive; it was impossible to tell when something might set him off and when it did, friends and family alike made themselves scarce.”

Frank Fenter died from a massive heart attack in 1983, just 47, just as he was trying to ink a new distribution deal with Warner Bros that could have saved the company. Phil Walden mounted a Warner Bros-backed Capricorn comeback in Nashville in the early 1990s by signing Widespread Panic, Allmans offshoot Gov’t Mule, and a then-unknown artist who went on to become a country music superstar: Kenny Chesney. Phil ended up selling the Capricorn catalog in 2000 for $13 million to Volcano Records and started a company called Velocette.

Phil died of cancer in 2006, aged 66, with no less than Little Richard attending his funeral. Alan Walden still lives today in Macon and turns 80 this year. The Waldens were inducted into the Georgia Music Hall of Fame respectively in 1986 (Phil) and 2003 (Alan), while Fenter was posthumously inducted in 2014.

When I first came across the Capricorn story around 2013, not much remained of the label or the original Capricorn building in Macon, and its history was in very real danger of being extinguished altogether. I got in touch with Alan Walden and Robin Duner-Fenter, Fenter’s son, about writing a book and screenplay based on the Capricorn story. They were keen to get something up and running. But for various reasons I had to put those plans aside. It would make a brilliant movie.

So I was thrilled when, in 2019, on the occasion of Capricorn’s 50th anniversary, Capricorn Sound Studios was reborn, financed by Mercer University “to leverage Macon’s music heritage to create Macon’s music future.” Today the complex even boasts a museum and gift shop.

If Matthew McConaughey, Will Ferrell, and Vince Vaughn ever get signed up to play the Waldens and Fenter in a Capricorn movie, I’ll be one fan buying a ticket.