This article originally appeared in the August 2003 issue of SPIN.

If you did something dangerously fun and outrageous in the late ’80s and ’90s that your parents didn’t like, you can probably thank Perry Farrell and Jane’s Addiction.

Stalking out of Los Angeles’ seedy underground after hair metal wilted, they revolutionized what rock music sounded and looked like, and became the Godfathers of the Alternative Nation.

This is their shocking history—from wiseguys and Fila headbands to goth surfers, transsexuals, Siamese Twins, Lollapalooza, and Carmen Electra.

Proceed at your own risk.

“HAD A DAD” (1959-76)

PERRY FARRELL, né BERNSTEIN (b. March 29, 1959): I was a Queens kid. I lived in Flushing for a few years, then moved to Woodmere, Long Island. But in the ’70s, everybody thought Miami was the spot. So my family moved down there and got into a better life, with a lake in our backyard and a little sailboat. It was fun, swimming and surfing.

JANE BAINTER: Perry’s dad, Al Bernstein, was a jeweler, a goldsmith from New York City. The Bernsteins were the type of New York Jews who move to Florida. His sister wore white-fringe leather jackets.

STUART SWEZEY: I’d heard his dad was some Jewish mobster guy, so I asked Perry about it. He told me stories, like Sopranos, Goodfellas stuff. Some guy would be found in a trunk with his dick cut off, stuffed in his mouth. I couldn’t tell you if he was pulling my leg or not.

FARRELL: My dad was a real character, a fun guy. Sharp, with a ton of style. Cared about his hair. Always drove a Corvette. Celebrities and regular people gravitated toward him. The wiseguys knew my dad, too. Everybody knew Al Bernstein. He was one of those guys walking around Miami Beach in the ’70s with a Fila headband and a bikini bathing suit with gold around his neck. He was a jewelry designer and repairman. I got a lot of creativity from him. My mother was a fine artist. She loved to take throwaway things and make art out of them.

CASEY NICCOLI: Perry’s mother committed suicide when he was a young boy. I met Al Bernstein when he was a little more mellowed out. Family legend has it that he was pretty hard-core in his youth. Perry blamed him for his mother’s death. Al was bringing a lot of women into the house and doing drugs and stuff when he was younger. The Al I met was an old man who was very sweet.

FARRELL: It wasn’t the worst of all situations, but I was a rebellious kid who didn’t like what he saw. I just wanted to get the heck out of there. What did I have to lose? So, at 17, I took the Greyhound out to California with a surfboard, some art supplies, an ounce of weed, and one phone number. That’s how I started my affair with California.

“UP THE BEACH” (1976-82)

FARRELL: I was living in my car in Newport Beach—an old, red Buick Regal big enough for two people to live in. If you park down by the beach, you can always shower or go surfing in the morning to stay clean. And you get yourself a banana or an orange for breakfast. You keep your clothes in the trunk folded neatly so you’ve always got nice clean threads to go looking for work.

NICCOLI: Perry’s family weren’t poor by far. But his father did not give him money or support him when he moved to L.A.

FARRELL: I got jobs as a dishwasher, and then I landed a gig as a driver for a liquor distributor. One day I was making a drop at one of those swanky Newport Beach places when this lady asked me, “Do you model?” And I said, “Oh yeah, I’m a model. I’m an actor. I’m a singer. I’m a dancer. Sure.” So she said, “Do you want to audition for our Friday-night show?” Within a few weeks, I was impersonating David Bowie and Mick Jagger at this club. I thought, “Man, I’ve got a great future here.” So I quit my job, and my girlfriend started selling bud. I had made my beginning in show business.

NICCOLI: He’d do Sinatra for them, too. Perry loved Frank Sinatra.

FARRELL: Sometimes we’d all go up to the Odyssey disco in Hollywood and get up on the risers and try to take the place over. We were just dancing like maniacs and goofballs, taking our shirts off and swinging them around. These talent agents would chat us up. One weekend, one of them said, “Look, I need a roommate. Come out here for good, and I’ll get you into show business. I’ll get you on a soap, and we’ll move from there.” So this guy took me in, and I moved from the beach to L.A.

“HUMAN CONDITION” (1983-85)

BOB FORREST: The cool bands from the original goth era had broken up—Joy Division and Bauhaus. But the scene was just kicking in here locally. All those second-generation [British] bands—the Sisters of Mercy, the Southern Death Cult, Flesh for Lulu—started playing around. And these local goth bands like Christian Death and Kommunity FK were getting a following. They really influenced Perry.

BAINTER: In the goth scene, we wore the white makeup and the black lipstick for a reason. We were fighting so many things that it was almost like we were already dead.

FARRELL: These people were such compelling figures because they grew out of isolation and made this tremendous personal statement.

SWEZEY: Mariska and Rich were two artist friends of mine who had a band called Psi Com. They found Perry through the local classified paper, The Recycler, and he became their lead singer.

MARISKA LEYSSIUS: My then-husband Rich and I had, like, 3,000 LPs, so we would just sit around and play music all day. Perry didn’t really know who Joy Division were, so I kinda turned him on to that.

FARRELL: The music of Joy Division hit me. I only found out about them after Ian Curtis died. This fellow was so saddened by love. I thought, “This is what a broken heart sounds like.” I could not stop playing that music.

LEYSSIUS: He didn’t really know anyone before joining the band.

FARRELL.: I was a loner. I wanted to get into a band because I wanted to have fun. The Paisley Underground scene was happening at the time, so I’d see a lot of ads for psychedelic bands: MUST LIKE THE BLUES MAGOOS. Stuff like that. I was actually in a Paisley Underground band for a minute. I got a paisley shirt and combed my hair into bangs, and then I thought to myself, “Shit, this is pretty shortsighted.”

SWEZEY: Mariska and I were organizing these events where we took people out in buses to the desert to see experimental bands. Just noise, you know? People like Boyd Rice would play, and Mark Pauline and Survival Research Laboratories would blow things up. Psi Com built up a following through those underground events.

LEE RANALDO: You had to get directions out there, and they didn’t release the map until the day of [the show] because they didn’t want people gate-crashing. We played one of them out in the Mojave Desert. Psi Com opened. It was one of Sonic Youth’s very first Los Angeles-area shows. A very trippy night, that’s for sure. We hung out with Perry that week—Perry and all his pet snakes and tarantulas.

FARRELL: There was the whole pay-to-play plague that was happening [in Los Angeles], where bands couldn’t get a gig on Sunset without paying for rental of microphones and pre-buying the tickets. We said, “Screw you all. Let’s go find a warehouse. Let’s go to the desert!” We would rent boats in San Pedro and rock out there with the Minutemen. [Psi Com] didn’t expect to be signed by anybody.

PLEASANT GEHMAN: Psi Com were nothing like Jane’s Addiction.

JOSH RICHMAN: They were an art-rock band. You never knew what the songs were. Was it noise, or was it art? I remember Perry onstage, and they’re playing this atmospheric goth rock, and he’s just banging on a fucking anvil. You couldn’t really sing along to it.

FARRELL: Psi Com opened up for the Southern Death Cult [which became the Cult], when Ian Astbury was still wearing that Indian hat with the feather in it. We opened up for Sex Gang Children, Gene Loves Jezebel, all these glammy, goth-type bands from across the pond.

NICCOLI: The first time I saw Perry was at a Psi Com show, and I immediately had this attraction. I said to my friend, “I want to have his babies.” A year later, I had broken up with my boyfriend, and I heard through some mutual friends that he was attracted to me, too. So I went to a Psi Com show and handed him a little note that said INSTANT MASHED POTATOES, and that was it. We started dating.

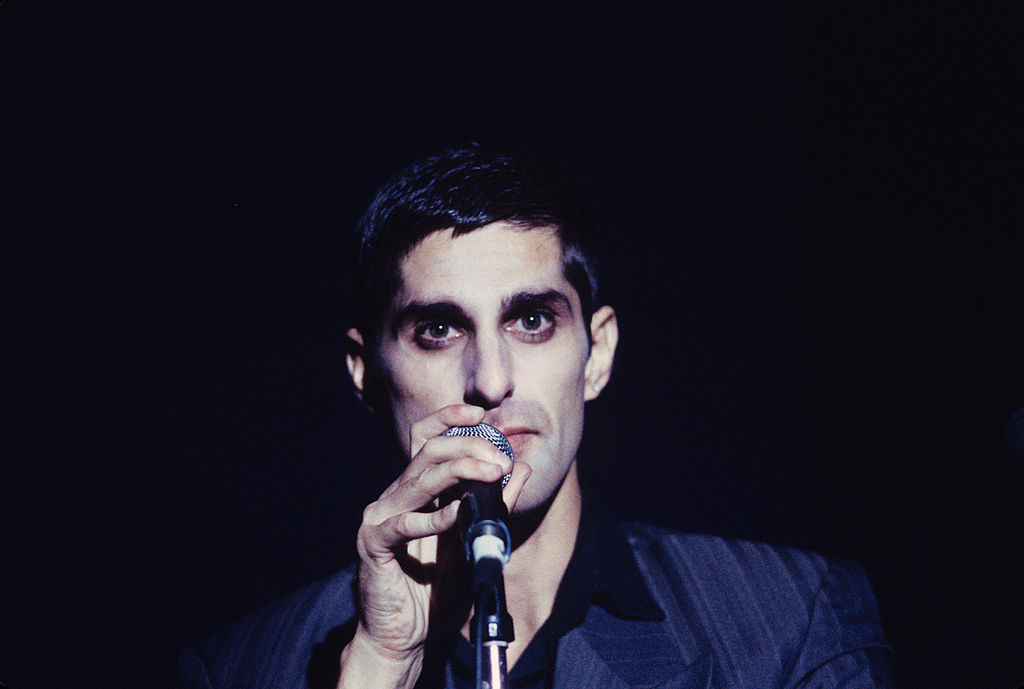

FARRELL: I thought Casey was a stunner the first time I saw her. She was like a punk Elizabeth Taylor. She stopped the show. She wore dresses and heels. Her hair was all chopped and dyed black.

SWEZEY: Perry was getting a group of people together to take over this older building on North Wilton Place. It was going to be this whole arts-collective thing.

FARRELL: I found this place that has come to be known as the Wilton House. I told the landlord that I would love to put curtains here, do the walls a certain color. I got him to believe I was this quiet, shy, gay interior decorator who’d be no trouble. He ended up getting 12 musicians, photographers, artists, their girlfriends, dogs, snakes, loud music, and ’round-the-clock junkie shenanigans. Cops were crawling around band rehearsals all the time.

SWEZEY: Perry would spend Sunday nights talking to his dad, pacing around while he was on the phone. He’d get really upset that the old man was putting so much pressure on him to succeed. Afterward he’d say, “My dad doesn’t understand what I’m trying to do, man. He says stuff to me like, ‘You gotta be a singer like Manilow, Perry. Manilow don’t answer to nobody!'”

BAINTER: When Stuart moved out, I took over his room at the Wilton House. There were a bunch of other people living there, like this ersatz goth band called Lions & Ghosts.

SWEZEY: Before Jane moved in, one of Perry’s house rules was no girls and no junkies.

CARLA BOZULICH: With most people I knew at the time, it always seemed like there was a scam behind everything they said—so that they could eventually score some drugs. Not with Perry. Perry always wanted to talk about music and art. Perry was a culture sponge. He talked to everyone that he thought had any experience that he might have missed. He just soaked it up.

DAVE JERDEN: Perry is like an antenna that picks up everything that’s going on, and then he regurgitates it through his brain. That’s his art.

NICCOLI: I had been very much into the Hollywood punk-rock scene before I met Perry. I loved Iggy Pop, X, the Ramones, and a lot of bands that Perry had never really been into. He’d never heard T. Rex. He had never even heard Iggy. He’d never heard all these bands that eventually became his biggest influences.

BAINTER: He was really into African tribalism and the ancient ritualistic arts of different cultures. He had a scarification done by some anthropology professor at UCLA.

RICHMAN: He was the first [white] guy to have dreadlocks. The first to have piercings.

FARRELL: Back in the day, I got pierced because I was hanging out around a lot of art punks and a lot of them were gay and into this mild to heavy bondage. They were so cool. But I had to take all my piercings out ’cause I’d be trying to surf out there with a tit ring, and the next thing you know, I ripped my nipple off.

SWEZEY: After a point, Perry felt Psi Com lacked the intense hard-rock energy that the Red Hot Chili Peppers had. Psi Com were sort of like mid-period Cure. Everybody was looking to the Chili Peppers as the model for success. Perry used to read about them in the “L.A. Dee Da” column in the LA Weekly. Perry would say, “Hey, all you have to do in this town to make it, man, is pull down your pants onstage!”

FLEA: I saw Psi Com at a party out near [Six Flags] Magic Mountain. This girl, whose parents had a ranch, had a party. It was real late. People were either nodded-out or had gone home. I was lying in the dirt, and this band came on that seemed like a regular sort of band. [But] then the singer came out, and he was absolutely out of his mind, on fire, shaking and quivering; every little muscle in his body was doing a different dance. I couldn’t believe it. I was like, “This guy is out of his mind—who is he?” And it was Perry.

NICCOLI: Eventually, he just outgrew Psi Com. He wanted something bigger—and more control.

BAINTER: Psi Com were going in different directions. Some of them were becoming Buddhist vegetarians, antisex, antidrug.

FARRELL: One day, I just got this feeling that I’m going to outgrow my circumstances, like, “I think I’m gonna make it.” But I had to get another band going, one that was happy, outrageous, and wild. I wanted to be able to sing truthfully. I didn’t want to have to fake being in a bad mood. That’s when I left Psi Com and started Jane’s Addiction.

BAINTER: I remember Perry saying one day when Psi Com were drifting apart: “Fuck those guys. I wanna rock!”

“THANK YOU BOYS” (1985)

ERIC AVERY: Carla introduced me to Perry. She asked me if I’d seen Psi Com, and I said, “Yeah.” And she said, “What did you think?” And I said, “I think they blow.” And she said, “Oh, okay, never mind.” And then I said, “No, really—why?” Carla said, “They’re looking for a bass player.” I was on the verge of selling my bass amp and giving up music.

FARRELL: Jane thought Eric was cute. And he was a cool bass player. He seemed like a wild kid, with this kind of half-cocked grin.

BOZULICH: Without Eric Avery, there never could have been any success for Jane’s Addiction. Eric had written the music, on his bass, years before he met Perry. I remember hearing those bass lines as far back as 1982. Eric started playing those bass lines, and Perry really seemed to hear himself in there.

FARRELL: I would look at [Eric’s] body language and I could tell what was going on in his head.

AVERY: I was an outsider to the Hollywood underground-band scene. I went to shows but didn’t know anybody, and I thought that this would be a cool way to just meet interesting people. Before that, I was camped in a West L.A. bachelor pad, bussing tables and shooting speed.

FARRELL: Eric was awesome. He loved the band Flipper from San Francisco. Flipper’s big thing was to stay in one groove without ever breaking it up. They weren’t even trying to put together super-well-arranged songs, but it felt great.

NICCOLI: Eric could play these superb melodic grooves, but he couldn’t make them into complete songs. Perry could cherry-pick the best grooves and make songs out of them.

AVERY: Our first jam turned into “Mountain Song.” Later, Perry said he thought that I was either a genius—because I didn’t do anything other than play the same notes over and over—or that I just didn’t know how to play at all. One day he told me, “I want to leave Psi Com. Let’s start a whole new band.” And I was down. Perry was great, an electric, creative guy.

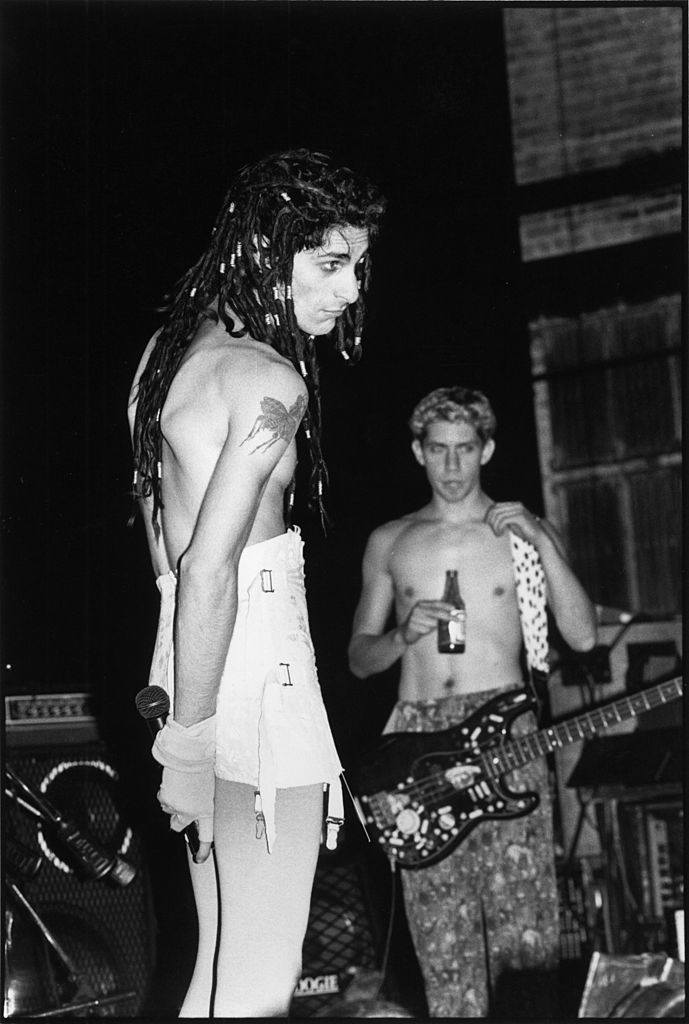

FARRELL: I’d go out there with just a drummer or with just Eric on bass and my vocal effects. I’d improvise lyrics, dressed in a see-through unitard—it was a big hit.

AVERY: One time, this disco song was playing while we were setting up, and I just kept playing along to it, and when they killed the houselights, we kept jamming on it. That’s where “Pigs in Zen” got started. Another time, I played on these chemical drums, and Perry sang, and that became “Trip Away.”

BOZULICH: After Psi Com broke up, Perry went through this furious change, like a caterpillar turning into a butterfly. He sat down with me one day and said, “I’m changing my name to Perry Farrell.” And I was like, “Huh?” And he goes, “Get it—Peri Pheral, Perry Farrell? Peripheral!”

NICCOLI: We were trying to think of a name for Perry’s new band. I said, “How about Jane’s Heroin Experience, like the Jimi Hendrix Experience?” And Perry said, “Jane’s Addiction.” So that was it.

BAINTER: They came into my bedroom and were like, “We have a great name for our new band!” I was like, “Uh, that’s not good.”

AVERY: I don’t remember who exactly was in the band when the name Jane’s Addiction came up. It was during our really early lineup with my boyhood friend Chris Brinkman on guitar. Chris used to play in his Jockey shorts onstage.

BAINTER: Chris Brinkman’s father was a business executive in Los Angeles. He married Jeanne Crain, who was this 1950s starlet. She was on the cover of Life magazine. Chris was very dynamic in the beginning, but he just spun out of control on drugs and eventually OD’d.

AVERY: I was sleeping with this prostitute named Bianca. She was awful, but she was going to bankroll us.

BAINTER: Her clients were toupeed Hollywood B-listers, like these wholesome, married game-show hosts with awesome tans and big grinnin’ teeth. A few Jane’s songs, like “Whores,” were inspired by her. She helped with money to rent venues and promote their shows.

FARRELL: Bianca was very sweet, if a little nutty. Nutty enough to want to manage us. So after Psi Com broke up, Bianca put up the dough so we could put on our own shows.

NICCOLI: We rented the Black Radio building [in L.A.], and that was a huge success. We promoted ourselves with Tex and the Horseheads and the Screamin’ Sirens!, who were, like, the big cow-punk bands at the time. We served beer and stuff, even though there was no liquor license. It was total DIY—like, 101 punk-rock style.

FARRELL: It was jam-packed ’cause of Tex and the Sirens!. We were bottom of the bill. Nobody knew who Jane’s Addiction were.

GEHMAN: The Black Radio show with Tex and Jane’s was completely insane. Beyond insane. Things got out of control so quickly. Tables and chairs flying through the air. Broken glass all over the floor. The only way I can describe it is that blur some shows get when the entire crowd is completely whacked out of their mind on different substances, and it’s like a swirling vortex, and you’re convinced that someone’s gonna die.

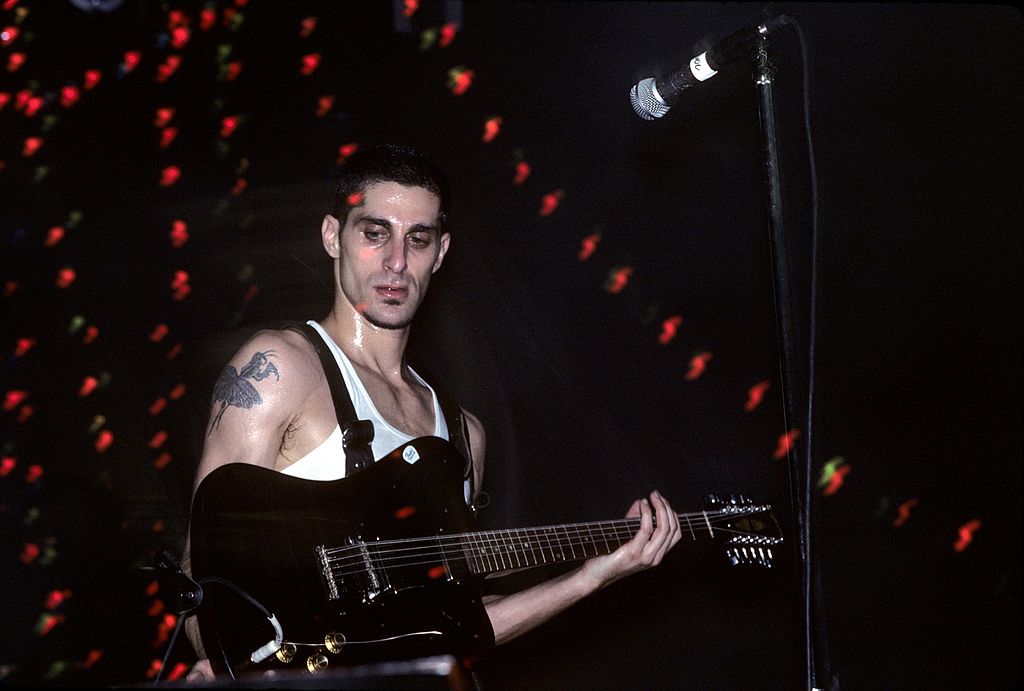

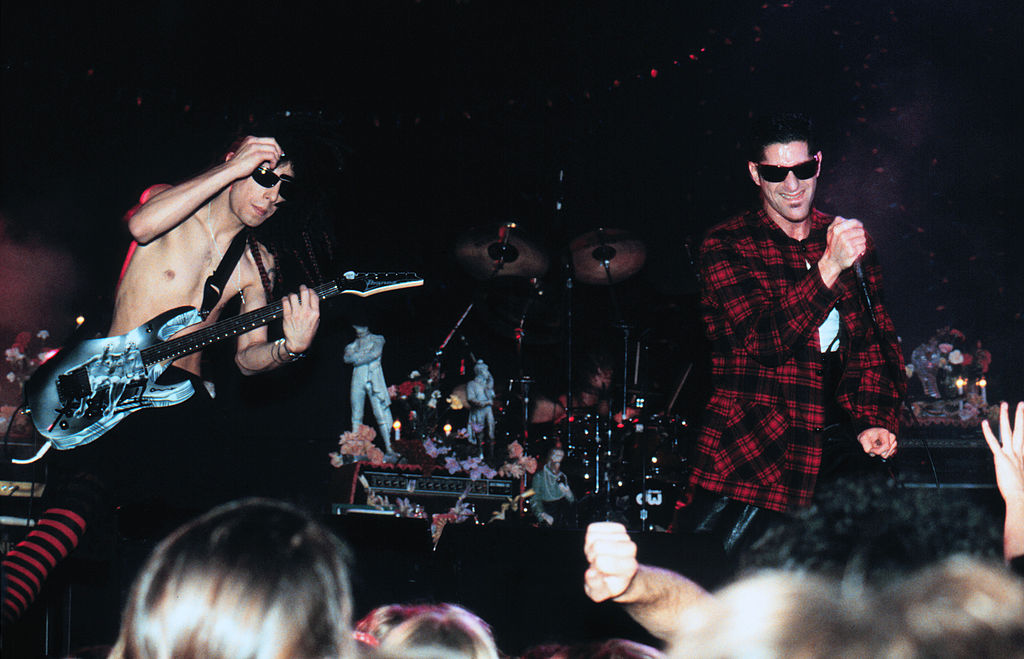

DAVE NAVARRO: [Stephen] Perkins and I were in a band called Dizastre, and we were fresh out of high school, playing our heavy-metal rock. One night, we went to see Jane’s Addiction, and we just loved it. They had the energy and power that we loved about metal, with a total abandon that we didn’t have any experience with.

AVERY: Stephen and David were friends with my little sister Rebecca, who told them to check us out. I remember seeing them up front in the pit at the Black Radio show. They were a couple of metal kids with long hair, and they were just rockin’ out, fist-pumping the air while we were playing.

FARRELL: Matt Chaikin, the drummer in Kommunity FK, had played that show with us, but it didn’t last. Everybody in that [version of] Jane’s Addiction had drug problems already, it seemed. Three rehearsals in a row, the guy wouldn’t show up, so I started to ask around, “Who knows a reliable drummer?”

STEPHEN PERKINS: They’d auditioned umpteen people until Rebecca finally said, “Why don’t you try my boyfriend?” The first song we jammed on was “Pigs in Zen.” I saw the smiles and their butts shaking, and I just went for it. After that I said, “Look, you gotta bring my buddy Dave down.” They had this guy Ed playing guitar with them at the time. Nice guy, but he wasn’t Dave Navarro, by any means.

BOZULICH: When David came in—that really made them irresistible to people.

PERKINS: The first song we ever played with Dave was “Whores,” and at that moment, the sound for Jane’s Addiction was born.

FARRELL: I thought, “Oh my god, they’re adorable.” Stephen and David—I called them Jane’s Teen Rock-a-Babes. They were like exuberant teenagers all the time.

NAVARRO: There wasn’t a unified thread between us. Perry had a whole freakish look of his own, like some skinny, bugged-out goth surfer in whore makeup with flailing dreadlocks. Eric was more traditional punk rock, and Stephen had this crazy Afro hair thing. I was kind of a hippie kid, a little ’60s-influenced Deadhead gone heavy metal. But you throw us together and it was a patchwork quilt—it doesn’t look like it makes sense, but it keeps you warm.

AVERY: People used to comment. “You guys are such a hodgepodge of styles. You look like four different bands.”

FARRELL: When you’re in a rock band, your best stylist is your girl. I’d borrow corsets and things from Casey. I’d wear a blazer and a corset and a pair of boots and a hat and some gloves and head out on a Friday night to mix it up.

BAINTER: Casey was working in a medical clinic and supporting them while Perry was free to pursue his creative interest. And she was giving him advice about everything—booking shows, just basic support, inspiration to be able to go and do it yourself. There definitely would never have been a Jane’s Addiction without Casey.

NICCOLI: The “Be Live!” show was another legend in early Jane’s Addiction lore. We had these classic motorcycles and transsexuals and fire-eaters on stage. We had a hot dog stand going, too. Hardly anybody showed up!

NAVARRO: It was a wild night, but an obvious financial disaster. Poor Bianca lost her shirt financially.

FARRELL: She was strutting around with the cash box, topless, with duct tape on her nipples.

AVERY: The guys in Thelonious Monster and Fishbone were there, and I think Anthony Kiedis was humping some girl in the pit.

NICCOLI: We didn’t realize there wasn’t any ventilation. It smelled like hot dogs and fumes. You couldn’t breathe or see anything. The hot dog cart was smoking. It smelled really bad.

FARRELL: All these macho biker dudes were mixing with punk rockers, artists, drunks from the Zero Zero Club, and Bianca’s clients—bowlegged old guys in sweaters reeking of cheap cologne, with white shoes and hairpieces. Transsexual dancers opened the show. It was quite the cast. There were also a bunch of underage metal-rocker kids from the Valley, friends of Dave’s and Steve’s. But the kids couldn’t handle their liquor.

NAVARRO: My friend drank himself into a blackout. I left him crashed on this couch, and when I came back, his pants were down around his ankles, and there was a transsexual hovering over him.

FARRELL: The kid should have just gone with it, chalked it up to experience, but he lost his mind—he ended up in a mental institution. It was the old panic trauma “Oh, no-o-o-o, now I’m gaaaaaay!”

“GONNA KICK TOMORROW” (1985-86)

NAVARRO: It was our first exposure to this elaborately seedy, fabulously filthy Hollywood underground scene that we’d only ever heard or read about. I was, like, 18 years old—in awe. I was over the moon. I’d finally made it at last.

NICCOLI: When you’re 27 in rock’n’roll [like Perry was] with nothing really happening, you think you’re old. That’s why Steve, Dave, and Eric were seven or eight years younger than Perry. He felt like he could mold them and they would forever do what he wanted. Eventually, they’d grow up, but by then he’d have gotten what he needed out of them.

BAINTER: I think Perry and Dave had a genuine bond, though. Both their moms had died unnatural deaths.

PERKINS: Dave’s mom was murdered. He was about 15. I met him when I was 14 and a half. I knew his mom, and I knew the guy that killed her. It was too shocking to even grasp, especially for a 15-year-old. As a best friend, I just tried to be there for him. We played music. We talked. We’d go meet girls. Whatever it took to free ourselves from the pain.

BAINTER: Dave’s parents were divorced, but they were on good speaking terms, and they would trade him off for weekend visitations. So one weekend he was with his dad, and he was going home to mom and his mom’s best friend, who he called his “Auntie.” They called and called, but no answer—very strange. Finally, Dave and his dad drive over, and they find his mom and Auntie bound and gagged in the closet—chopped up. His mom’s boyfriend, who was quite close with Dave, is just gone—never heard from again. He had even played softball with Dave and had been a second dad to Dave for, like, four or five years.

NAVARRO: I used to focus on the tragedy and how certain negative things in my life have defined me. It took a long, long time to realize that.

GEHMAN: Heroin was really taking its hold. There weren’t a lot of people doing it in the early to mid-’80s. It took hold at the end of the ’80s and continued, as we know, into the ’90s.

BAINTER: We all were total suckers for drugs.

KARYN CANTOR: Perry would say, “We all have an addiction,” but we’d all sort of say, “Well, it’s her problem” or “It’s his problem.”

NAVARRO: I admit I totally blew it with drugs back in those days. My intake was certainly a factor in the eventual demise of the band the first time around. What do you want me to say? There was always five pounds of heroin, all the booze and coke you wanted, all the girls you wanted—all looking for nothing but guys in bands. And I wasn’t even old enough to legally drink yet.

NICCOLI: When Perry and I first started dating, we did heroin together a few limes, long before it became a problem. It was just us getting high, sitting around making Christmas cards for our friends. We thought of it as a way of opening up our creativity.

MARC GEIGER: Three of the four members—not Stephen—were very into heroin, as well as many other things, and it was clearly a big influence on the band and their behavior. Perry definitely believed that drugs fueled creativity.

BAINTER: “Jane says, ‘I’m done with Sergio.'” Yeah. Sergio was a drug dealer who lived nearby. He was El Salvadoran and sold drugs to send money home to his family. I was strung out, and he was using that to manipulate me. My parents divorced, and my mother and her new husband bought this house in the south of Spain. I had the opportunity to go over there, but I couldn’t because I was strung out. I had this idea that it was this big reward of mine that if I could just get sober, I could go away to Spain. You know, “I’m going to kick tomorrow.”

AVERY: Sometimes we’d do acoustic jams on the porch at the Wilton House. I’ll never forget when Jane asked us if we’d play a sad song for her, and I had to shake my head and say, “Jane, we just got through playing ‘Jane Says,’ one of the saddest songs in the world.”

JERDEN: When I first heard [“Jane Says”], I just thought it was another good song they’d written. I didn’t know it would become the “Stairway to Heaven” of modern rock.

DEAN NALEWAY: My partner Peter Heuer and I started Triple X [Records/Management] in ’85. We were out in the clubs all the time looking for new bands to build a roster. We’d already staked out a few bands when we saw Perry handing out flyers, and we were like, “Pretty interesting-looking guy. Who is he?” We wanted to do a three-record deal with Jane’s at first. They were unknown; we had a little bit of clout. But Perry had his eye on the big picture. He knew that three records for us was too much. He really wanted to get his show on the road.

FARRELL: We told Warner Bros. we definitely wanted to sign, but we wanted to come out on our own label or an indie first and then grow organically from there. We said, “We appreciate all the money you’re offering, but we need to come out on Triple X with a live record first.”

NALEWAY: We invited everybody down for a show at the Roxy. We put up everything we had to make that live record [1987’s Jane’s Addiction]. We even sold our cars.

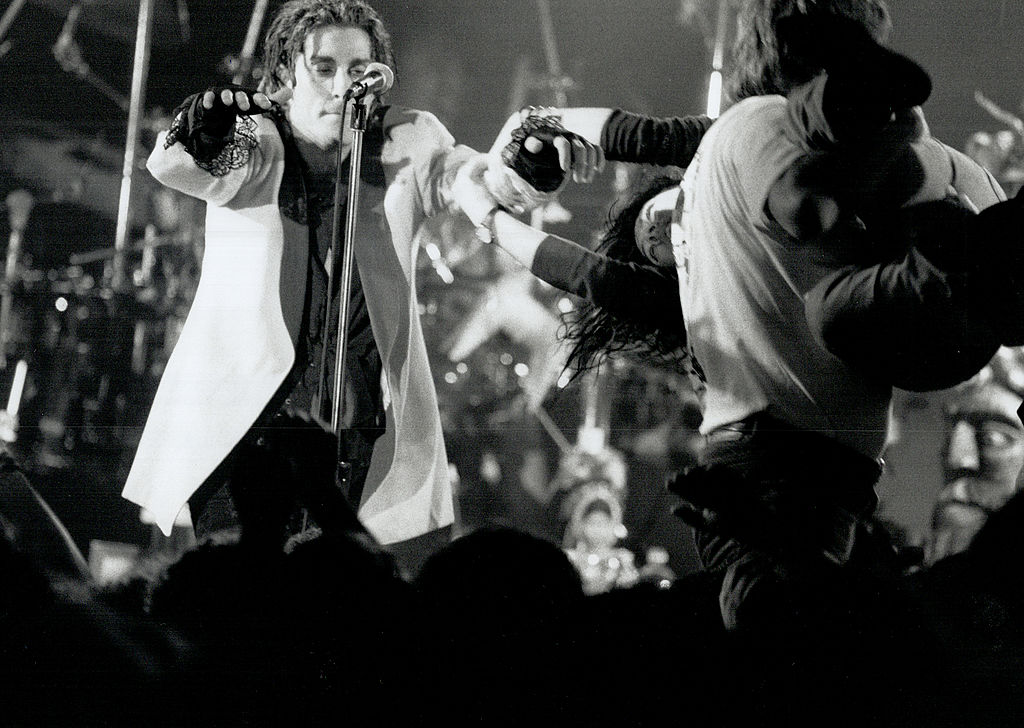

FARRELL: I behaved like a prick and cussed out the entire record industry in the audience. I was telling everybody they needed to lose weight. I was like, “Fuck you all—you can all kiss our ass.” It was typical overwrought histrionics. But we made sure to put on a great show because it was being recorded.

FORREST: Anthony [Kiedis] and I were watching [the show at the Roxy], and it was just so mesmerizing and powerful. It was everything that everybody who had bands hoped to accomplish. It gives me chills still, how great they were. We walked out to the car, and Anthony was all quiet and I was all quiet, and then he said, “What are you thinking?” And I said, “I’m thinking why do I even [bother to] play music.” And he said, “Yeah, me too.” And he just started the car and drove away. They were that far ahead of everybody else.

SCREAM (1986)

NALEWAY: Everybody who heard the live record loved it. But it still took us a while to spread the word. Dayle Gloria and Mike Stewart, who ran Scream, helped a lot.

DAYLE GLORIA: One reason Jane’s Addiction and Scream became so close was because they’d gotten themselves eighty-sixed from every other club in town. I was DJ’ing at [Club] Lingerie the night Perry flew off the stage and jumped up on the bar and knocked everything off. Every glass, all the ashtrays, the cherries, everything. Jane’s was banned from there, so I said, “Come and play for me. I don’t care if you break anything.” The club grew with them. We grew together. If somebody would cancel, it was like, “Let’s call Jane’s Addiction.” They became like the house band.

RICHMAN: The scene that gathered around Jane’s was ancillary to this thing that was going on with Guns N’ Roses and Faster Pussycat, L.A. Guns and Jetboy. Those bands were playing the Troubadour and the Strip, but Jane’s was selling out the Lingerie, the Palace in Hollywood, the Country Club in Reseda; they also got the Lhasa Club and the Powertools downtown art crowd. Then they started to play regularly at Scream.

GLORIA: Guns were playing to the whole Whisky-Gazarri’s-Strip thing. We represented the anti-Strip at Scream, because of the darkness of a lot of the things we were doing. We were also seven or eight miles away from the Strip in downtown L.A., where only the more adventurous rocker types would go. The Cathouse where Taime Downe and Guns hung out was more of a sleazoid tattoos, strippers, and rock’n’roll kind of thing. All the Cathouse guys looked like Bret Michaels from Poison, and the chicks were slutty Tawny Kitaen types. At Scream, all the guys looked like Ian McCulloch [of Echo & the Bunnymen], and the girls were all Siouxsie [Sioux] clones.

SLASH: We rehearsed in the same little hole-in-the-wall practice studio [as Jane’s]. One day, the Jane’s guys were coming out as we were coming in, and it was very weird—we never exchanged words. It was sort of like one of those high school things where two sides quietly face off.

CHARLEY BROWN: Jane’s hated Guns N’ Roses. Guns were their mortal enemies, as far as scenesters and stuff.

SLASH: Guns hated everybody.

FARRELL: [One day], we went over to Dayle Gloria’s place for a barbecue, and there’s Iggy Pop on the floor, listening to our song “Pigs in Zen.” There’s one of my idols, listening to our music. I got too nervous, so I just left. Dayle followed me with Iggy and said, “Where are you going? I want you to meet Iggy.” He said, “Man, I think you guys are hot stuff; I want you to come on tour with me.”

GEIGER: The first Jane’s tour was opening for Iggy Pop. Then, mostly dates with the likes of Peter Murphy, Love and Rockets, Gene Loves Jezebel, and so on. The goth thing was still the musical bent for Eric and Perry, who were the leaders of the band.

BROWN: The best show they ever played was [when] they broke up onstage at the Limelight in New York. Ian Astbury and Billy Duffy from the Cult came out and started doing Led Zeppelin covers with them. Backstage, Dave Navarro was incredibly drunk. Right in the middle of Billy Duffy’s guitar solo, Dave came out and unplugged him and just started wailing on the solo. Duffy was kind of strumming on his guitar, like, “What the fuck just happened?” and walked offstage. Then Perry and Dave went wild and got in a fistfight. Perry threw him into the drums, and the whole set just fell apart.

NALEWAY: Once, at UC Irvine, Perry didn’t want to open for Love and Rockets, so we had to talk him into doing the show, and he said, “Okay, but I’m gonna whip my dick out.” He had his usual corset on and these rubber pants that he’d cut a hole out of so his penis could hang through. Near the end, he threw the corset into the crowd and was dancing around with his dick bouncing up and down. Campus cops showed up in droves to arrest him for indecent exposure. Perry ran upstairs to the dressing room, and we had to hide him in a closet until they gave up.

FARRELL: As long as I could whip out my dick, I knew I was alive.

NOTHING’S SHOCKING (1987-88)

FARRELL: Things were hot. Enter the record companies. Soon they were all buzzing around.

NAVARRO: I don’t remember much about the bidding war. All I remember was, they took you to Hamburger Hamlet on Sunset for record-label dinners back in the ’80s. Always the same place. I don’t know why.

AVERY: All of a sudden, we had MCA—labels like that—taking us out to dinner, but we knew we were never going to sign with them, because Warner Bros. was just the right place. It was like visiting a college dorm. You could walk down the hallways and hear music blaring out of everyone’s office—what a great vibe.

NALEWAY: Their hearts and minds were already set on Warners. We could get anybody on the phone, from the top man down, which impressed the hell out of Perry. And the Warners deal gave them 100 percent creative freedom. But we played around anyway and milked it for some good meals.

FARRELL: I never ate so well in my life.

NICCOLI: When he put his mind to something, Perry always got things done. He was a leader. He stuck his nose into everybody’s business, and sometimes he pissed people off. But he always got what he wanted.

FARRELL: I liked Dave Jerden’s work on [the Brian Eno/David Byrne album] My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, so I was excited to work with him. He knew how to do a lush production with a hard-rock band.

JERDEN: I jumped at the chance to make a record with them. What other band since X—and then, even further back, the Doors and the Velvet Underground—could have segued from songs about serial killers and terminal-addiction despair to singing beautiful, tender love songs about summertime? Perry gave me a tape of all these bits and pieces of music that the band had. It had this feeling like our entire culture was in there, distilled into one idea, and that idea became Nothing’s Shocking.

PERKINS: Nothing’s Shocking was a combination of everything in the world today. Even back then, there was reality TV when [notorious serial killer] Ted Bundy was representing himself in court.

JERDEN: Perry has always been interested in the dark side, and with Ted Bundy, I don’t think you can get any darker than that. He gave me this video of Ted Bundy, and he said that he wanted to use some of the dialogue, so we worked it in. They were going through a really tough time personally. Dave Navarro was still having a rough time [with his mother’s murder]. And there were tensions between Eric and Perry.

AVERY: Our relationship deteriorated into an unspoken standoff; it was kind of like the Cold War, where both sides knew that all-out war would be devastating. It created this weird détente, this nonverbalized agreement not to escalate. So we never did. It’s surprising, with all the out-of-controlness, that he and I never got physical with each other. We didn’t even yell. In more roundabout, passive ways, we’d say things to hurt each other’s feelings.

NICCOLI: Early on in the band, Eric got drunk one night and tried to pick up on me. We were both really wasted. When I told Perry what happened, he basically stopped liking Eric. Perry just never got past that. He hated him forever because of this stupid incident. I’d kissed him back, but I was just drunk. It was nothing—just stupid puppy-love stuff.

FARRELL: But did she tell you he also went on to confess his undying love for her? That was uncalled for. I’m the kind of guy that doesn’t try to steal girlfriends. C’mon, man, you never try to pick up on your bandmates’ girlfriends—even in rock’n’roll, man. I mean, please.

AVERY: Things got really bad between me and Perry. We had a meeting to figure out the publishing. I wanted it to be split equally between everyone, but Perry wanted 50 percent for writing the lyrics, plus another portion of the remaining 50 percent for the music. Dave, Stephen, and I wound up getting 12.5 percent apiece.

NICCOLI: Perry could argue, “Well, without me, it would have just been a great bass groove in his garage forever.”

JERDEN: I drove to work at the studio one day, and Perry was in his car in the parking lot with Stephen and Dave, and they were pulling out. Perry says, “The band just broke up. There won’t be any record. See ya!”

AVERY: Warner Bros. called an emergency meeting, because Perry said it was his way or no way. We actually broke up for a day. Perry said, “It’s got to be this way, or I’m walking.” And we said, “Let’s walk.” But we compromised and obviously kept going. David made a T-shirt for our next show that had 12.5 PERCENT spray-painted on it.

JERDEN: We finished the record, and then the real trouble began. When we turned it in, someone at Warner Bros. was saying, “We’re concerned about this record. It doesn’t sound like anything else.” It was the time of Guns N’ Roses and the metal-lite thing. And this was before they’d even seen the cover!

STEVEN BAKER: In 1988, nine of the 11 leading record chains refused to carry Nothing’s Shocking because of its cover [which featured a photo of the Farrell /Niccoli sculpture of two naked, Siamese-twin nymphettes].

FARRELL: Well, obviously nudity doesn’t fly well at Walmart.

PERKINS: We had to issue the record covered with brown paper.

BAKER: We [Warner Bros.] financed a video for “Mountain Song,” which contained a few frames of Casey’s bare breasts, and MTV wouldn’t play it. So Perry said he wanted to release it as a single on video. He was like, “Okay, so MTV won’t play my video? Fuck it, we’ll sell it to break even. Let the kids who like us see what we’re doing.” Then he added 20-plus minutes of band footage [Soul Kiss]. It’s commonplace on CDs now.

JERDEN: When the record came out, the mainstream rock press just trashed it. Rolling Stone said, “This band is full of shit.”

FLEA: I remember the first time I heard Nothing’s Shocking. Perry had just finished up recording, and we were on our way to a friend’s house to watch the big Tyson-Spinks fight. On the way there, Perry was like, “Oh, this is my new record, listen to it.” And then I realized what a great, great band they were. It was just a big, weird day. I heard Jane’s music for the first time, Tyson knocked Spinks out in the first round, and then I came home and got the call that [Chili Peppers guitarist] Hillel [Slovak] was dead.

JERDEN: I went into a record store and asked this guy with glasses and a ponytail behind the counter if he had Nothing’s Shocking. And he looked at me and said, “Are you kiddin’? I wouldn’t carry that piece of crap in this store.” I knew then we were either going to make a big belly flop or we were really gonna do something.

NAVARRO: KXLU [at Loyola Marymount University] was the first local station to play our music. The first time I heard us—I think it was the “Mountain Song” demo—you would have thought I was signed up to be on the first civilian flight to the moon. It was just the biggest deal.

FARRELL: The success of R.E.M. really helped what they now call “modern rock”; it helped it catch fire. Suddenly, college radio began to become important to the record industry. One tour we’re playing a club in Phoenix, trying to get paid while this guy is choking our manager and pulling a gun on him. Then [by the Ritual de lo Habitual tour] we’re selling out Madison Square Garden.

BAKER: There were some limitations on the first Jane’s album. We didn’t have a video on MTV, and there weren’t that many [alternative] stations. They didn’t mean as much. They didn’t have the numbers they do now. Nothing’s Shocking did about 200,000 to 250,000.

JERDEN: Nothing’s Shocking eventually found an audience all right [more than a million copies sold]. There’s not one person I talk to today who’s in their thirties who didn’t listen to that record in college. Nevermind was a fucking classic record, and the press has marked that as the beginning of this big change in alternative becoming mainstream. But it wasn’t. Nothing’s Shocking was. It didn’t have the same sales, but it made the same cultural mark—and it made it first.

BROWN: That whole [Seattle] thing came out of Jane’s. There wasn’t anything like us at the time. If Jane’s hadn’t happened, Seattle wouldn’t have happened. The scene was bubbling up, and Soundgarden and Mudhoney were the first ones out there, but they were too paranoid of L.A. [music-business people], and they hesitated and missed the window. Nirvana ended up getting the credit. Jane’s got mired down because we were the first ones cutting through. Even though the sheep in the music industry hated us, they realized that this was happening, so once they didn’t get Jane’s, they started going for all the bands that opened for us, like Soundgarden.

CHRIS CORNELL: I think a lot of people out there [in Seattle] think that rock’n’roll changed in the early ’90s when Nirvana showed up, and everyone had a big hit. But it didn’t really work that way. There were bands like Jane’s Addiction that laid the groundwork. Musically, [Jane’s] had a huge impact on Soundgarden.

HENRY ROLLINS: Jane’s was the only band I saw in those times who had that I-will-follow-them-anywhere type of crowds. There were a lot of great bands around at that time, but Jane’s had this tribal thing happening with their fans. It was very powerful.

FLEA: Without a doubt, to me, they are the most important rock band of the ’80s.

“THREE DAYS” (1988)

“I’m either going to be a famous artist or a famous waitress.” —Xiola Blue (Ben is Dead magazine)

NICCOLI: Perry wrote a song called “Xiola” for the Psi Com album. She was Perry’s girlfriend before we met. She was maybe 13 or 14 when Perry met her. She was this really colorful, crazy, risk-taking, artsy girl who was a lot of fun to be around.

FARRELL: Well, I guess the word that people would probably use for her is precocious. When I first met her, she was wearing a chartreuse and yellow dress, and her hair was green and in dreadlocks. And I think she was wearing yellow lipstick and yellow tights, and she had very light freckles and a very pale face. She was the kind of girl who looked like a 1920s cigarette ad, except in vivid ultra color.

BAINTER: Xiola came back from the East Coast to visit Casey and Perry, and they had a long weekend. Xiola had her hair in braids, and she influenced Perry to pierce his nose and to wear his hair in braids, too.

NICCOLI: We all had a physical relationship—me, Perry, and Xiola. She spent three days with us, hence the song “Three Days.” We got high and danced with each other and made love and listened to beautiful music. Made flower bouquets. It was really romantic. We had a room we called the “Love Garden” decorated with plants and tapestries and candles. Xiola was so colorful and creative, but also a hard-core heroin addict. She was a trust-fund baby. Friends found her overdosed in her apartment in New York. She was only 19 years old.

FARRELL: When she died, it was just kind of a jolt. An electric jolt.

BAINTER: Perry was devastated. It was like the first wake-up call—”Oh, maybe all this fun with drugs isn’t all it’s cracked up to be.”

NICCOLI: We did the sculpture for the Ritual de lo Habitual cover in honor of Xiola. It’s Perry, me, and Xiola, like we’re these abstract bodies lying on a bed. Xiola’s family is so opposed to anything related to Jane’s Addiction. Perry talked up the Ritual album cover, where he’s in bed with two lovers at the same time, and one of them is their daughter, who’s dead. It really made her family angry.

FORREST: Far be it for me, of all people, to be sounding like an old fogy, but celebrating drugs and sex is going to have some dark fallout—I can guarantee you.

“JUANA’S ADICCION” (1989-91)

“Señores y señoras, nosotros tenemos mas influencia con sus hijos que to tiene. Pero los queremos. Creado y regalo de Los Angeles, Juana’s Adiccíon.” [“Ladies and Gentlemen, we have more influence over your children than you do. But we love them. Born and raised in Los Angeles, Jane’s Addiction.”]

FARRELL: That’s Cindy Lair at the beginning of Ritual de lo Habitual. She was the Latin Marilyn Monroe. We met her, and I thought, “Holy Mother, this girl is just gorgeous.” I actually wrote it out, but I don’t know how to speak Spanish fluently.

JERDEN: It’s a ballsy way to open an album. It’s like, “We have your kids.”

FARRELL: The theme of Ritual? Well, uh, I guess it’s pretty self-explanatory. We were having a lot of sex. In those days, I pretty much would run away from people to hang out with my partner—a partner or two—and have some fun. And [the album] was a reflection of it. I like to build things on the run. It’s a certain time of your life, and you’re in a certain state of mind, and if you can grab the things around you and place them together, they start to tell a story. So I guess that was the story of my life right there. We came up with the title when we were doing seven shows at the John Anson Ford Theatre. I think Casey and I came up with “Ritual of the Habitual” for that particular event. I thought it was funny.

JERDEN: We were supposed to start recording Ritual in June or July, but because of his rift with Eric, Perry just didn’t show up for weeks. We started recording without him. Eventually, Eric and Perry decided they would just come in at different times to do their stuff.

BAKER: They played as a band on the first record. With the second record, it was more like they were laying down their parts separately.

NAVARRO: I found out recently that we were in such poor condition that we had to stop and take a break for several months.

FARRELL: Was it me that time out had to be taken for? Casey was really sick, and she had to be taken to rehab, and she wouldn’t go unless I went with her. Maybe that’s where this break comes from.

NAVARRO: I have absolutely no recollection. I couldn’t even tell you who was in bad shape, but I’m certain I was one of the culprits.

FARRELL: Me, too.

AVERY: I was clean at this point. I just had this sense of why am I even in this band anymore? What’s the point? This just doesn’t have much to do with me anymore. I felt so apart from the rest of them.

JERDEN: There was one magical day when I got them all together and we cut “Three Days.” I set the whole band up, they played it, and that version is what’s on the record, note for note.

NAVARRO: My memory of recording Ritual lasts about five minutes. In my head, we spent five minutes in the studio.

JERDEN: After we finished Nothing’s Shocking, I got a call from Warner Bros. saying, “We’re very concerned about this record.” And I’ll be damned if I didn’t get the same call after the second record.

FARRELL: I turned in the cover artwork, and they said, “Oh, boy, here we go again!” [Warner/Reprise CEO] Mo Ostin and [Warner Bros. Records CEO] Lenny [Waronker] said people were getting arrested for selling albums that any local law-enforcement type decided was pornographic. They said retailers were so cautious that the record could wind up selling 1,000 copies.

BAKER: We came up with this idea of printing the First Amendment on a separate cover. Few people bought it. Most fans bought Perry’s original version.

FARRELL: I only agreed to do a second cover if they’d guarantee to run the original uncensored.

JERDEN: When the label told us that “Been Caught Stealing” was going to be the single, we were surprised. I hate to classify it as a novelty song, but we just considered it a fun track. We were adding some vocals to it one day, and Perry’s dog was trying to get into the vocal booth with him because one of her toys was in there. She happened to bark on cue, and we kept it.

TED GARDNER: Ritual was the [album] that took off. The commercial success stemmed from “Been Caught Stealing,” the single. That was the only [Jane’s] single that made it to radio in any mainstream daytime airplay. It was one of those quirky little songs. No one really took any notice of it until Perry said, “Hey, let’s do a video for this song.” It was timing.

JOHN NORRIS: Back then, the word alternative did sort of mean something, and that sure as hell was an alternative to everything else MTV was playing at the time. There was drag in it, played for laughs, years before the Foo Fighters did it. There were no chicks with big, sprayed hair. And you’ve got your lead singer, who you’re supposed to see, wearing a stocking on his face. There was something in the air, and Jane’s was pushing the boundaries. The network played the hell out of it.

NICCOLI: When Perry got the first draft of the “Been Caught Stealing” video [that I directed], he called me and said it was horrible and it sucked and that I had ruined his career. When I heard we’d been nominated [for MTV’s Best Alternative Video], Perry didn’t want to go [to the Video Music Awards]. He didn’t feel the need for the fanfare; he’d rather stay home and smoke crack. I wanted to go, because I worked really hard, and I heard [their manager] Ted Gardner would accept the award on behalf of “Jane’s Addiction,” and it triggered something in me, like “Why would I want him, who doesn’t even respect what I do, to accept an award for something I worked so hard on?”

PERKINS: We should’ve been together in one place at one time [for the MTV Awards] and gone up as a band. But there were communication failures, no focus, no sharp intention. It was scattered, and it was shown right there on national TV.

FARRELL: I was nice and high. I just didn’t feel like getting out of the house; it wasn’t that important to me, the whole attitude of MTV and what it stood for. Casey wanted to go, so I said, “Have a good time.” I didn’t watch the show, but eventually I saw a clip. She went up there pretty loaded.

NORRIS: I call it the “train wreck.” But it was entertaining. She was ranting about Perry and what a genius he was while Navarro was trying to stick his tongue down her throat.

NICCOLI: Perry disappeared the day before the show with some chick he’d picked up at a 7-11. He saw the show sitting in her bed. That’s why I made such a fool out of myself when I accepted the award. I was so drunk and sad about Perry. I don’t remember Dave kissing me. He was pretty out of it himself. I was in a total blackout. I’m still really embarrassed, but, oh well, it’s only rock’n’roll!

GARDNER: It was decided that the band would tour and then Jane’s Addiction would break up and go their separate ways. That was between the band and myself. No one else knew. So we all picked the places we wanted to go—Australia, New Zealand, Yugoslavia, Vienna. We played Rome at Easter and stayed in this quaint, beautiful hotel two blocks from the Vatican. In the café next door, they were selling espresso and heroin, which was kind of interesting.

PERKINS: The Ritual tour ended at Lollapalooza, and that was the end of the band, basically. Communication between Perry and Eric was gone.

FARRELL: The tour behind Ritual was half the reason we wound up unable to stand each other.

PERKINS: We’d come to L.A. to do shows but wouldn’t sleep here for more than a week. We did three nights at the [Hollywood] Palladium and then kept touring. Came back and did four more at Universal Amphitheatre. More touring. All in support of Ritual. It may have broken the band internationally, but it may have also broken the band’s spirit.

ALTERNATIVE NATION (1991)

NAVARRO: I think of Perry as the godfather of alternative rock. I call him “the Don.”

JIM ROSE: At that time, there was nobody more in tune with alterna-America. That guy’s ear was so firmly to the ground you’d need more than a Q-tip to clean it.

FARRELL: Lollapalooza was really a party. The concept is just throwing a party with you as the host. So what are you going to have for the people there? You have one day of their time. And you have a field or someplace that will allow you to rent it. It’s really no different from any of the other parties we would throw in Los Angeles, except it’s now become a macrocosm of them. It’s the same attitude.

GARDNER: [Jane’s] were due to play the Reading Festival [on their last tour], but Perry lost his voice, and we couldn’t play. Stephen Perkins and I still went [to England], and we met up with Marc Geiger from Triad Artists Agency [who represented Jane’s Addiction]. Marc and I were lamenting the fact that America did not have a music festival along the lines of Reading. So we came back from Europe for the American leg of the [Jane’s] tour, and Marc brought up the idea, “Why don’t we invite a bunch of our friends to play on the tour and create something like Reading.” Marc Geiger planted the seed. Perry watered it, christened it, and when it popped up it was Lollapalooza.

GLORIA: Perry approached me and Mike Stewart about doing Lollapalooza with him—when he’d just had the idea. We had dinner at Tommy Tang’s [restaurant], and me and Mike were looking at him like he’s a total nut. Of course, millions of dollars later….

GEHMAN: I can definitely see how Perry would have been inspired to start Lollapalooza, coming from places like Scream, which always had really diverse bills. There’d be some total punk band, some speed-metal band, some band that was kind of arty and melodic, all playing on the same night. He knew it would work, and he took it to the bigger, national level.

ROLLINS: I had a great time. It was wonderful to play and then get to see the Butthole Surfers and Ice-T back-to-back, and then later on see Jane’s Addiction—every night.

ROSE: We [the Jim Rose Circus Sideshow] were probably our nation’s first beloved “Jackasses.” The kids used to faint. We’d call them “falling ovations.” That particular era was the debut of snorting a condom in the nose, pulling it out the mouth, putting it in the mouth, and blowing it out the nose. We had the amazing Mr. Lifto, who did his unconventional weight-lifting act. He lifted incredible amounts of weight with his ears, nose, tongue, nipples, and the part of him that was most a “mister.” Before Lollapalooza, it was very difficult to get a gig in the U.S. because promoters are less likely to take a risk on the unknown. But I got the call from Perry, and it was all about his belief in what we were doing artistically and how it would work perfectly with what he was planning. I’m talking to you from my home in Maui right now, and I guarantee you that prior to meeting Perry Farrell my only goals were a pop-out couch and a toaster.

GEHMAN: Oh, God, the Jim Rose Circus was better than most of the bands on that tour.

ROSE: We debuted an act on Lolla ’92 where a guy would thread seven feet of tubing into his stomach via the nose. And on the outside end of that tube was a clear plastic cylinder. We’d fill that cylinder with the most god-awful concoctions, pump it into his stomach, have him bounce around a little to mix it up, and then pump it out of his stomach. Because most of the concoction was beer, we called it Bile Beer. We’d pour it into glasses and offer it to the audience. Basically, we offered throw-up. One day, Chris Cornell showed up and drank it. Well, that made tons of press. And the next day, Eddie Vedder shows up and drinks it. Then Al Jourgensen from Ministry. Flea drank it. Each time one of these people drank it, there would be massive amounts of press and hundreds of kids would be jumping onstage to drink it, too. It finally narrowed down, in the bile-guzzling derby, to Eddie and Al, who would come on daily and have a chugfest to see who could outdrink the other. At the end of the tour, Eddie was ahead by about a quart.

FARRELL: I liked walking the grounds of Lolla, passing through the art gallery, and seeing the chair that was made out of nails. Then I’d go through the film tent or watch people listen to poetry. I remember bungee-jumping while Soundgarden were on. And, of course, having sex during the day is always exciting.

GARDNER: In ’91, there was an element of risk. It was like, “God, what if this is a dismal failure?” In ’92, we were getting offered Corvettes. There was a promoter that said, “Play my venue, and I’ll get you all Corvettes.”

JAMES IHA: Lollapalooza ’94 was one of the coolest rock bills I’ve ever played on: the Beastie Boys, the Breeders, Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds, George Clinton and the P-Funk All-Stars, L7, Boredoms, and Green Day. Stereolab and the Flaming Lips on the second stage! I have memories of the Beasties and Tibetan monks playing basketball. Everyone was welcome to play, although most of the bands weren’t that athletic. I certainly never expected to see Nick Cave at the free-throw line.

RANALDO: In some ways, the tour [Sonic Youth] headlined in ’95 killed Lollapalooza, because I don’t think it was as successful as some of the other tours. Maybe it got to be too much to sustain it. Maybe Perry got tired of dealing with it.

GARDNER: It depends on how you want to measure success, but we never had an unsuccessful year.

FARRELL: Finally, Ted just stopped caring. Or I just stopped caring, by my behavior. The worst thing that happened for me was that I lost the respect of the people who worked around me. And they decided to make all the decisions without me in mind. I had no chance to balance the show out. That’s when the art got lost.

GARDNER: We got lazy. We got successful. We got fat. We forgot what the core of Lollapalooza was, which was the music. We started to look at how to make it bigger. “Can we get the Beatles to headline? Oh no, one of them’s dead.” Things like Ozzfest and Lilith Fair took the traveling-circus concept and fine-tuned it to a specific demographic.

CORNELL: Booking Metallica had a huge impact on the fraternal aspect of Lollapalooza. The band was always wanting to hang out, but their crew was putting police tape across everything. So you couldn’t walk in and say, “How’s it going?” because it’s fucking police-taped off!

ADAM SCHNEIDER: Perry left William Morris [Agency] and Lollapalooza in a very public dispute over the booking of Metallica to headline Lollapalooza in 1996. Then he went out and did the ENIT Festival that same year with Porno for Pyros and Love and Rockets co-headlining. [Love and Rockets, as well as Black Grape and Buju Banton, later pulled out of ENIT; due to poor ticket sales, many of the dates were canceled.] All the money Perry made on Lollapalooza ’96, he poured into ENIT, because he felt strongly about putting together a lineup that he wanted to see. It was with total respect to Metallica. Metallica are their own thing. It just wasn’t the Lollapalooza aesthetic defined by Perry.

FARRELL: I’m not interested in the money. I prefer to draw from the spirit world.

RICHMAN: Perry would put his own cash into anything he believed in. He’s succeeded, he’s failed, but he’s always put himself out there.

GEHMAN: Lollapalooza just became the corporate co-opting of something that I had basically grown up with and participated in. It was good for what it was, but eventually it became like a parody. I mean, it was literally parodied by The Simpsons—Homerpalooza.

FARRELL: I wish I’d have been one of the cartoons. They didn’t even get me in the episode.

“STOP” (1991-96)

AVERY: I was so fed up, I finally decided to split. I really didn’t have any feeling for it anymore. I just felt so uncomfortable being so unliked. And I was nearly clean. I’d watched something that was really close to my heart grow into this machine that was created by Perry and the record company and Triad. So I said, “Dave, I’m splitting.” And he went, “Oh, okay, cool. Me too.”

FARRELL: We just didn’t take care of each other.

NICCOLI: Our film Gift was meant to be a full-length feature film. We just named it Gift because it was like our gift to the fans. It had no structure, no real story line. We had no script. It was a lot of documentary and fantasy mixed together. We went to Mexico and filmed our wedding in a place called Catemaco; it’s a big witchcraft town. We got married by a Santería princess. We had to be cleansed before. They roll an egg over your body. Then they break the egg open and if it’s black, it means that there’s evil in you. We hired these two goons who presented themselves as seasoned filmmakers, but they were just fans who really hadn’t done anything. It ended up a nightmare, because we didn’t really get along with them. They kept trying to say it was their movie. I was on drugs and not in my right mind, and neither was Perry. By the time the film was finished, we weren’t together anymore. It just took so much out of us.

NAVARRO: I was not only self-destructive, but destructive of everything around me. I regret my attitude and my behavior back then, but I don’t regret the outcome so much, because that was in ’91, ’92. Everything happens for a reason. Perry and Stephen got to do Porno for Pyros; Eric and I went on to do Deconstruction, which was a very experimental album. And after that, I joined the Chili Peppers.

FLEA: The whole time we played with Dave, I felt like we were adequate. We were doing the job, but we didn’t really connect a lot. The thing that made the Chili Peppers great was the fact that we just improvised like crazy. We’d get together to rehearse and jam for three hours. That’s really the force of our band. Dave wasn’t into doing that. He wanted to play songs; he didn’t really wanna jam.

NAVARRO: They have a great work ethic, and they’re spiritually minded, healthy fellas. I’ve been asked, you know, “How do you feel about making one of the least successful Chili Peppers records [1995’s One Hot Minute]?” And my answer has always been, “Not only do I love that record, but it is, to this day, the most successful record that I have ever been a part of, commercial-wise.” When I listen to that record, I hear myself growing as a musician, and I couldn’t have had a better group of guys to learn from.

FLEA: We were playing at the Grand Olympic Auditorium [in Los Angeles] when I was playing bass in Jane’s a few years later, and all of a sudden, I felt this amazing energy coming out of Dave. He was on fire. Just going crazy and playing his ass off. Completely putting his whole heart and soul into it, and I realized I never felt that from him in the Chili Peppers. I just don’t think he felt comfortable enough to really let loose in the Chili Peppers, whereas with Jane’s, that was really his home.

PERKINS: The first Porno for Pyros record was the result of three months of playing in my garage. There are some great songs on that record: “Black Girlfriend,” “Packin’ .25″—but it wasn’t the next Jane’s Addiction. We wrote the second record, Good God’s Urge, in Tahiti and Fiji and Mexico. It was less hard rock, but I thought the songs were wonderful, too. We just never put the time and energy into pushing it. We never toured real hard and never got involved in trying to break it.

FARRELL: Porno was more degraded than Jane’s. I had so much fun in Porno. I was close to everybody. It was the first time [guitarist] Pete DiStefano was ever involved in a big rock situation. And he lost his mind. It was very exciting to be there as we gently lost our minds together. But eventually I just disappeared.

“RELAPSE” (1997-2001)

RICHMAN: The people want Jane’s.

PERKINS: Dave and Flea started hanging out with us and helping out with Porno after Pete DiStefano was diagnosed with testicular cancer shortly after Good God’s Urge. Knock on wood, he survived, and he’s doing great. It all started when we did a song together [“Hard Charger”] for the [1997] Howard Stern movie Private Parts.

AVERY: Perry called [to ask me to rejoin], so we got together for lunch. I was looking at it more as an opportunity to heal the rift on a personal level. I wanted to say, “Let’s each agree to just go our separate way as friends.” It was going that way until he asked me if I wanted to come back; when I said no, he just flipped out. He was so angry. And I said, “I’m really sorry it’s going this way, Perry. I’d hoped that we could part as friends today.” And he said, “We were never friends!”

FARRELL: He knew very well why I was asking him to lunch—to invite him back to play and tour with us again. He could have said politely, “It’s not going to happen.” He could have saved me the heartache of winding my hopes up and then embarrassing me at the end of the meal by saying no. But it was Eric’s mind game to see me squeal and squirm. That’s kind of the wrong time to say to a guy, “Hey, I know I just crushed you, but let’s be friends.” Ever see a cop beat the crap out of a guy, and then when he’s putting him in the car he says, “Watch your head”? Fuck you.

PERKINS: We just decided, “Let’s do Jane’s Addiction with Flea.”

FLEA: They asked me [to play bass on the “Relapse” tour]. I tried to be as faithful as possible to what Eric did. I didn’t want to interject my own personality into it at all. It was like being asked to play in the Jimi Hendrix Experience or Led Zeppelin or Joy Division or some great epic band. I wanted to honor that. I didn’t want to change it at all.

SCHNEIDER: Relapse was an aptly named tour.

NAVARRO: I don’t remember much of it.

FLEA: There was some severe, crazy decadence going on. It started off being absolutely incredible—some of the best feelings and shows and energy that I’ve ever felt in my life, complete power. But it ended up being sporadic, then terrible. Because of drugs, it became a complete fucking mess. The focus got diluted. People still liked it, but I just knew what it could’ve been because I knew what it was in the beginning of that tour, and it was a mighty, mighty thing.

FARRELL: I have a friend named Aaron Chason. We’ve been friends since ’91. I worked on Gift with him. We were trippy friends. Aaron disappeared and then resurfaced, having graduated from yeshiva, which is Talmudic studies. In 1999, he came to me proclaiming Jubilee, which is a 50-year cycle where we are encouraged to free slaves and bring people together through massive parties and gatherings. And he figured I was the guy for the mission. He set out to teach me about Jubilee, and we went on to study Torah and Kabbalah. And when the hour of Jubilee struck in 2000, ironically, that brought the band back together to record. I’d gotten into electronic music and computer software and had written a solo album, and I wanted to go out and proclaim freedom, and I needed the best band I could think of to do a tour, and that was Jane’s Addiction. So we got back together for a tour [in 2001], and we ended up raising money and freeing people out of Sudan, people that were in captivity.

PERKINS: We raised $120K on the Jubilee tour and took it into Africa and freed slaves, actually bought slaves, $4K a slave. Used Jane’s money and did something, and I feel like we can do it again. Let’s do something for the environment.

STRAYS (2001-03)

AVERY: I think the power that we had in the ’80s was that people could feel religiously about the band, and I don’t know if that will hold up as well if it’s marketed in a way that’s just like more of the usual rock hype. I don’t know whether or not it will speak to people. We’ll see. I would just hope that the band continues to make some decisions with at least a nod to what it used to be and what it means to people.

NICCOLI: It’s different from what I thought Perry would end up doing with his life. I just didn’t think he had to reunite the band. Not that it’s a bad thing. It’s none of my business, but it’s just a weird thing to me. I see Perry as being somebody who might have evolved into something really unique and different without ever having to go back.

FARRELL: Personally, I care a lot less about the past than I do about the future. I only care about the past if I was part of something great. Now that turns me on. And this much I can safely say: I feel in my heart I was part of something great.

JERDEN: [New Jane’s Addiction member] Chris Chaney is an amazing bass player. What’s interesting is Chris Chaney played with Alanis Morissette, and now Eric Avery is playing with Alanis Morissette. They kind of switched spots. But I’m going to be honest with you. To me, Jane’s Addiction is Jane’s Addiction when it’s got Eric Avery in it.

BOB EZRIN: Let’s say they’re pretty well drug-free. Each one of them has his own peculiar, individual personality and character. And they’d spent so much time apart that it’s really pronounced. I’m sure it was like that for a lot of other bands, like the Eagles or Aerosmith. When they come back together, it’s difficult defining a common point of view or even a common interest.

FARRELL: I’m not a guy who believes in 100 percent abstinence unless you want to give a blessing. I’ve offered up certain chemicals as a sacrifice, but that’s mysticism. I still drink and smoke [marijuana]. But I moderate. I would never be drunk when I have to take care of my kid. I had a little boy [Yobel], and there is no room for that when you have a kid who is helpless and needs to be taken care of.

NAVARRO: I’m really looking forward to starting a family. [My fiancée] Carmen Electra has been an amazing, grounding element in my life. She’s just done nothing but bring positive energy into my life; in a lot of ways, I’ve changed spiritually as a result of this relationship.

CARMEN ELECTRA: I want a medium-size wedding. My last [marriage, to Dennis Rodman] was what it was, but I want to have a real one. I want this one to be very traditional. I want to do it right this time.

EZRIN: My job on [the new Jane’s Addiction album] Strays was to bring a sort of commonality to the process and make everyone think it was a group effort again, and not just a bunch of solo projects trying to be strung together. And that wasn’t hard at all. They are so naturally in love with each other.

FARRELL: Working with Bob Ezrin on the new album meant a lot to me, because I knew that Dave loved Pink Floyd’s The Wall, which Ezrin produced. Dave learned The Wall [as a kid]. He can play the whole album, so I knew he’d instantly have a lot of respect for him. I knew we’d be in good hands.

ROSE: I still have all the faith in the world that Perry will create some-thing very innovative for this upcoming season, although it’s still a little murky what that might be. I grossed my first million dollars on a kid who had six piercings and three tattoos. That’s your neighbor today. I couldn’t give a ticket away for that.

FARRELL: A musician spreads his message through microphones and singing and records and television and now computers. Now the phone is linked to the computer and TV. I’m interested in linking all of them in a live situation and a festival situation. That’s where I’ve put my time and effort for the last years—trying to get a festival fully interactive and fully wired. That’s what’s going to be different about Lollapalooza. I’ve put it back together; I don’t want to be last in line on something that I helped create.

ROBERT HARVEY: I don’t know much about the history of [Lollapalooza]. I’m just into seeing Jane’s Addiction. My bass player got me into them. They’re massive, yeah.

PERKINS: To me, the future of Jane’s Addiction is better than it ever was. At 18, I thought we would be the next Led Zeppelin. We’ll make ten records. We’ll do this our whole lives. Here I am at 35, and I’m still in Jane’s Addiction, so I guess in a way it came true. Each of us had a vision. Back then, there was a sharp focus on those visions, but it diluted quickly. Now we can hold the focus.

NAVARRO: It’s 2003, and we’re in the best shape we’ve ever been in as a band and as friends. I believe that everything happens for a reason. And that we wouldn’t be here in the best shape of our lives and ready to embark on an amazing tour if we hadn’t broken up in 1992. So in certain aspects, I’m grateful. We have a chance to correct some of the wrongs that we did to each other.

FARRELL: My father got to see me perform a few times before he passed away. It’s funny, ’cause I used to whip my cock out all the time, and it’s always like, “Fuck the world, that’s how it goes.” So one night, there’s my dad, and it’s the first time he’s gonna see me, and I’m thinking, “Am I gonna kinda shy away from this now, or am I gonna just do my thing?” And I said, “Man, I gotta do it.” So out goes my cock, and I’m rockin’ out, and I put on a really energetic performance, and after I get offstage, I see my dad come flying at me with a towel. He put it around me because I was sopping wet. He wasn’t trying to hide my nakedness. He was putting the towel around me because he didn’t want me to catch cold. ■

Additional reporting by AnnaMaria Andriotis, Andy Downing, and Amanda Petrusich