Tegan Quin doesn’t want to be perfect.

She wants to be in a band. She wants to tell stories and play instruments and make mistakes and feel the electricity of liveness where audience members and performers alike dance and cry and connect.

She wants to improve the lives of queer women and trans people while moving conversations about investing in queer justice away from the outdated, one-dimensional gay marriage narrative. But most of all, after over 20 years in the industry, she wants to — and deserves to — stand in her power.

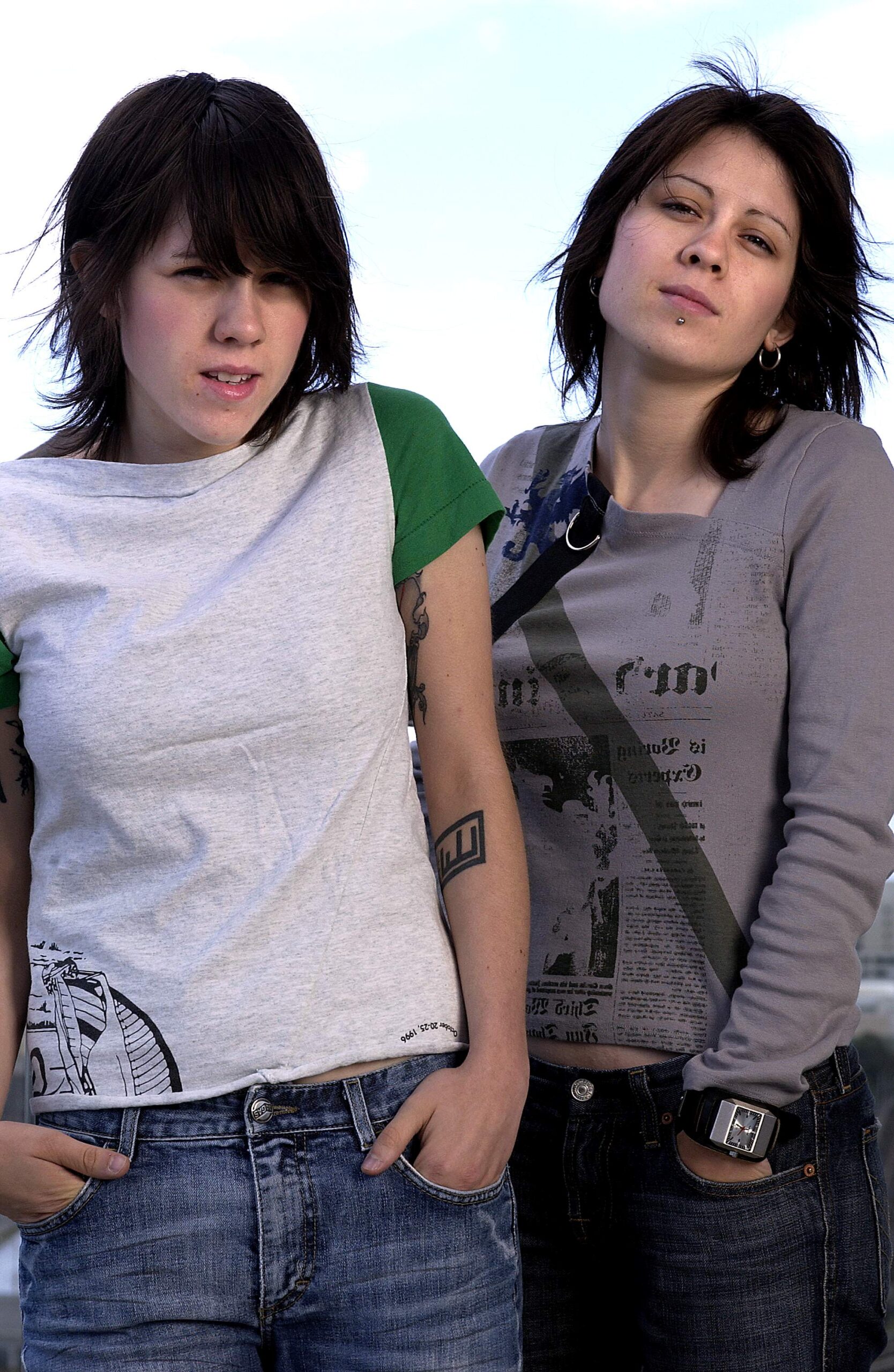

A long-time disruptor in the indie and pop worlds, Tegan and Sara — Sara is Tegan’s twin sister— have made a name for themselves as artists and icons who aren’t afraid to challenge the status quo. While High School, their memoir and subsequent TV show, straddles a rare space between lesbian nostalgia and emergence hardly ever afforded in mainstream pop culture, it is still a current and urgent intervention and a breath of fresh air for queer audiences.

Their 10th studio album, Crybaby (which came out Oct. 21), is another disruption. It’s a departure from major-label style and combines glitchy, lo-fi experimentations with their knack for guitar-driven hooks and pop sensibilities, treading new ground while sonically anchored in their past. A sobering and passionate look at queer coming of age as full-grown adults in a fraught time, Crybaby feels like a statement on change, a meditation on the duo’s own relationship with nostalgia, thanking it and ultimately burning it down to clear a path toward an exciting yet uncertain future.

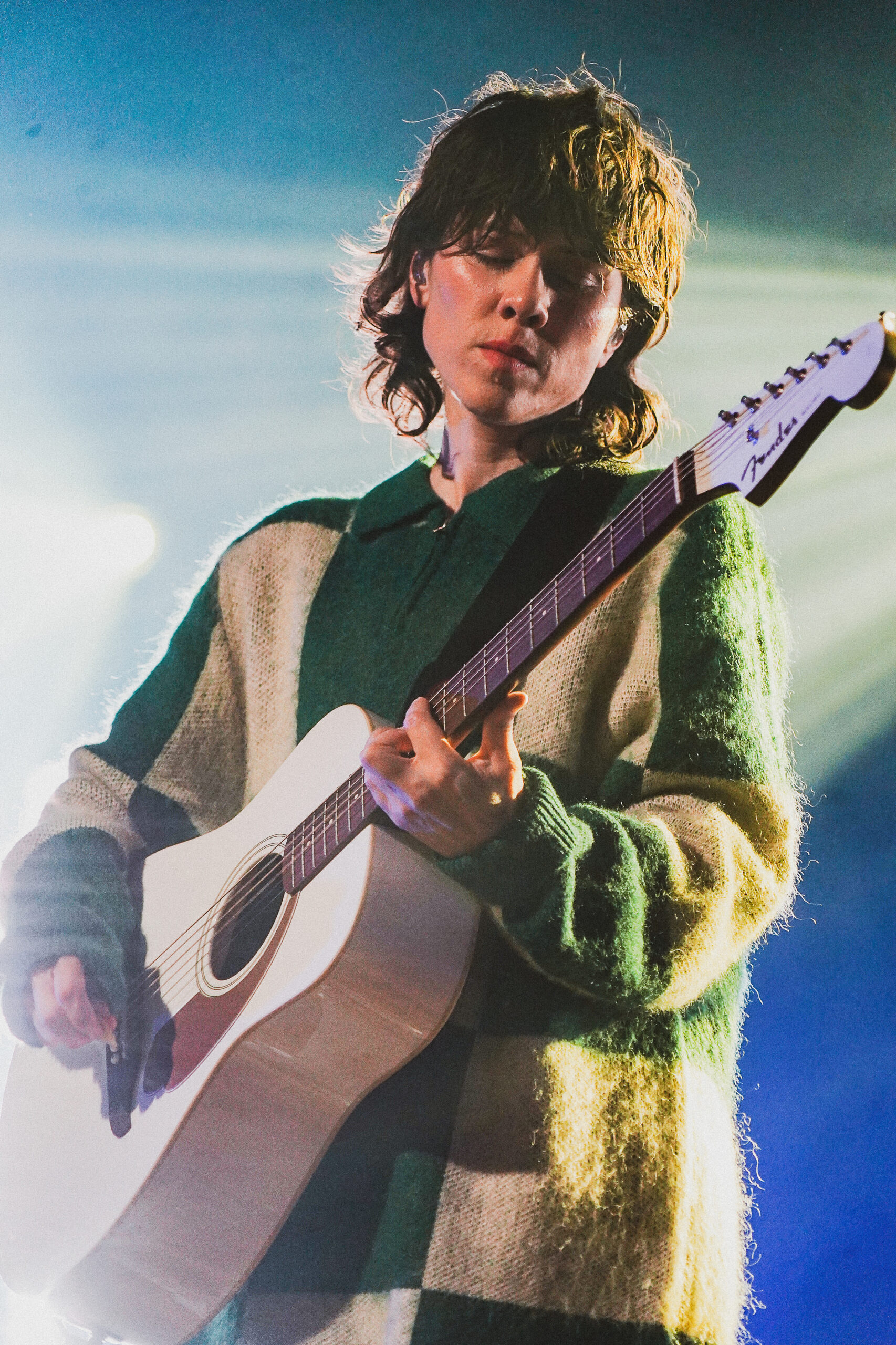

We spoke to Tegan about Crybaby, their renewed sense of intensity, and everything from Telecasters to laryngitis, and that special gig, before they played the Henry Fonda Theatre in Los Angeles recently.

SPIN: I heard that you recently got sick and lost your voice while on the road. Fans were keeping the gigs going by singing your parts! Can you tell me a little about that?

Tegan Quin: It’s been amazing to be onstage. The audience is so alive — it is really electric. I got laryngitis, and I couldn’t say [anything]. I literally could not make a noise. And it was heartbreaking for me.

We’ve been touring for over 20 years. A point of pride for us was that we would just play through anything! Heartbreak, death, food poisoning, strep throat, whooping cough, diarrhea, like just anything, you know — you just never cancel a show. You just never ever let people down. There were so many times where we were sick. But it was like, well, we’re opening for The Killers; we can’t miss this opportunity. You know, and our margins are always so tight on tours. We just have always played through everything.

The first night Sara performed for me. She did as many of the songs as she could herself. We record the show every night, so I have a live vocal of me. We kind of piped that into a few of the new songs that Sara doesn’t know as well. And we just said to the audience, “Our choices here are: You can sing along with Sara and sing along with my recorded vocal or we could cancel the show.” And people went nuts. They were like, “No, of course, we don’t want to cancel the show!” It ended up being one of my favorite shows of all time.

Has anything like that ever happened in the past?

It’s only happened two other times in our career. It happened when we did The Con Anniversary Tour in 2017. On the last night in Austin, Texas, I woke up and had laryngitis and had no voice. We went to a print shop and had the lyrics to the entire set printed out and made into booklets and then gave them to everyone. All 700 people came, and they sang the show. People said it was their favorite Tegan and Sara show ever.

I think we’re very unique. I don’t think every band could do this. I think we have a very specific relationship with our audience. Sara lost her voice a couple nights [on the Crybaby tour] and we had to cancel one show, and then I had to carry the show for her. And it was special. It reminds me how lucky we are in those moments.

I feel like your songs become these cornerstones of people’s life experiences in similar ways to some visual or tactile feminist art. They actually become an important part of people’s lives. In Anaheim, before you got into some of the stuff from So Jealous and The Con, you said that you were going to play some songs that changed your life, and that they might have changed some people in the crowds, too.

Yeah, I think what you just said is 100% dead on. Our ethos, my job, is to make you feel something about your own life. When you hear our music, if you’re thinking too much about what I wrote it about or my life, then I haven’t done my job very well. [Laughs.] When I meet fans and they ask questions about our band, they want to know what Sara and I like about each other’s music and what inspires us. And then when you start to dig in, they want to compulsively tell you what the songs mean to them.

That’s really informed how Sara and I present our music but also how we write music. I want to make sure that whatever I’m writing feels relatable. And, you know, I still want to be me. I’m still queer; my experience is still my experience. I don’t want to erase my experience in the music. But I do want to make sure that anyone could listen to it and find some point to connect to.

I think Crybaby is a return to that in a lot of ways. Sara and I have been slow-walking back from pop and from “We want to take over the industry.” Well, we never said that, you know, but we were always just like, “We want to queer the industry. We want to be in the mainstream. We want people to know who we are. We want to reach more people.” That was the last decade, and we’ve been slow-walking back from that because we realized that [we] don’t want to be on the radio and don’t want to have to do three radio visits a day, and I don’t want to go to L.A. and write with the biggest pop producers, and I don’t want to be the biggest band in the world.

My priorities have changed, and my concept of legacy has changed. I want you to listen to our new album and be like, “This is my life. This is relatable to me and these people. They could be my friends.” Because I could be your friend.

Those dance records felt like a big “fuck you” to the industry that honestly felt so cool to see.

It was a political move! And I think that’s why our audience didn’t abandon us — because we made it very clear in the marketing and branding of the album was that we felt that Heartthrob and the idea of like “the sex symbol” and being popular was not afforded to women, especially queer women, and that we were tired of being pushed into the margins. So it was very political. We still wrote all the songs, and we were still heavily involved in the production. And, you know, we worked really hard to retain that connection with everybody. Anyone who was like “They’re selling out” was just lazy. Actually, a lot of people came around in the end. It’s such a funny thing: I know some super fans who were very, very disturbed by Heartthrob. And now they’re like, “Oh, I love that record.” But it just takes time.

I feel like a lot of your work took some time for some people to understand.

Every record takes time, and that’s good. I think art shouldn’t always be instantly consumable. It shouldn’t always be instantly loved. One of our favorite stories about The Con and So Jealous, both beloved records of old-school Tegan and Sara fans — those records were not beloved when they came out. They were challenging our audience; the media. And the initial round of press that came out about them was not complimentary. People were confused by the decisions we were making. And that’s what we do.

Every time we finish an album, we dismantle it. We take it apart, and we put it in a storage unit. And then when it’s time to make a new album, I go visit the storage unit. And I’ll take a few items home with me. But the record stays in the storage unit. I’m not going to make that record again. I’m going to make something else. It’s going to disturb you potentially, but give it time — it will sink in because one thing we never change is us. We are still there. We’re still the voices; we’re still the artists writing the songs. And just like you’re evolving, I’m evolving.

I think sometimes people forget that it is political to make dance music, especially for queer people. I saw what you did as a mainstream version of “Gravy Train” and “Le Tigre”. Grief and sadness are important feelings, but you also have to have space for joy in the revolution.

Absolutely! Heartthrob was a very specific thing, and then Love You to Death was our dark pop dance record. We went out and were like: No opening, no support tours; we just want to headline and connect with our audience and make everybody dance and cry. Crybaby feels really different — it’s a return to our roots in a lot of ways. We’re disruptors. That’s what we do. I’m not ever trying to intentionally push people away from us, but we’re going to do what we want. And I think this era of Tegan and Sara is very about what we want.

What is it that you want?

Well, I want to be in a band. I want to play instruments. I want to make mistakes. I don’t want it to be perfect. I don’t want to just play to a wall of programming. I want our audience to move; I want them to feel; I want them to emote; I want them to sing! I want standing room. Maybe next year I’ll want to play [seated] venues. We want to do what we want to do and play songs that we want to play. We want to make television; we want to write books; we want to tour less. I want to sit in my power, and I want to use it for good things.

What’s going on with the Tegan and Sara Foundation?

We focus a lot on our foundation. One of our big programs is called Community Grants. Every quarter we’re rushing $20,000 to $30,000 out the door to small grassroots organizations with micro-grants. The first round was related to COVID-19. So it was a lot of LGBTQ centers that wanted to move online or wanted to get LGBTQ kids backpacks with books from queer authors, to give them stuff to do during the pandemic.

Elliot Page is on our board, and he brought to our attention that there’s a lot of domestic abuse that happens in queer relationships, and we don’t really talk about it. We did months of research and investigation. And the big takeaway was that there aren’t very many organizations that focus on that. We wrote a lot of grants to [help] existing organizations start running programming to help survivors and people who are suffering from domestic abuse within the LGBTQ community. So that’s been a huge focus for us for the last year.

Vans came aboard last year and funded the entire LGBTQ summer camp program that we have, which was $75,000. It’s not that much money in the grand scheme of things. But it allows us to send hundreds of LGBTQ kids from rural communities and low-income families to LGBTQ summer camps. We’re now sending kids to 28 different summer camps nationally.

I know it’s so hard to write grants and get funding for programs like these.

It’s hard. The hardest part of the foundation was realizing that it’s really hard to raise money, especially for queer women. So much of our focus has been on queer women, trans women, and women of color. And it’s hard when people are like, “But gay marriage!” We have to remind them that these things are unrelated.

When the pandemic hit, we were really worried because a lot of the ways we raise money are through the community. And we raise it a lot from Tegan and Sara [gigs]. We donate $1 from every ticket sold, sell merchandise, and literally pass buckets, which is how women raise money. And we were like, “Fuck, how’s that going to work during a pandemic where we can’t tour?” When you’re in financial hard times, which we’re currently having with inflation, women just have less money, especially queer women. Our board really came together, though.

One thing that’s been really amazing is seeing how many people really do continue to fund. Because of the gay marriage movement, there was a focus on very specific organizations like HRC and Trevor Project, [the work they do is] amazing, but these organizations already have so much money. I think one of the coolest parts of Tegan and Sara Foundation is being a connector to grassroots organizations. A lot of people don’t necessarily even give to Tegan and Sara Foundation, but they come to us and want to understand our network. And then they give to specific grassroots organizations via us. And, and that’s been super meaningful. I’m really proud that the Tegan and Sara Foundation is a big part of being that conduit to bring everyone together to talk.

You had so many guitars at the House of Blues the other night. Do you have a connection with your gear?

We are very proud of the fact that we’re not gear people. And we’re not obsessive about our instruments. I will admit: Everything that we have on the tour with us right now is about aesthetic.

But that being said, we have an amazing relationship with Fender. And over the years with companies like Martin and Gretsch, but Fender have been aggressively generous and provide us with a giant cache of guitars at the beginning of every record cycle. We auction them all off for the foundation, and we’ve raised hundreds of thousands of dollars through our guitar auctions. Right now we’re playing a lot of Telecasters. I’ve never played a Telecaster in my fucking life, and I love it! I was like, “Oh my god.” I just had no idea.

With acoustics, it’s really hard because I play mostly parlors and minis, and they’re not always great-sounding guitars unfortunately when you amplify them because they tend to be obviously smaller and thinner. But I do think that Fender has some great parlor-size guitars that aren’t overly shellacked, and so they tend to sound a little more rich. I love a lot of the acoustics we’re playing right now.

From So Jealous to Sainthood, we cared a lot more about guitars. That was when we really got into Gretsch. And there were certain guitars that we got really obsessed with because they were more “rock record” guitars, you know? We were working with Chris Walla, and he was like, “I totally get it. Guitar stores are a nightmare.” He had, like, hundreds of guitars and was like, “Just play all my guitars and whichever ones you love, let’s just get you a relationship with those companies.”

I hate that it was a man that had to help us get there. But I think we didn’t really care that much. When we started to play really nice guitars, I was like, “Oh, yeah, these are really nice.” But some are just really heavy guitars. My body hurts. I don’t want to play heavy guitars! Then we started to play parlors, and I moved to Arlo Guthrie’s, which I really love. For many years, we played Gibson guitars. And I have a bunch of mini Martin and Taylor minis, and they’re beautiful. That’s all I play at home.

What’s the connection between ice cream and Crybaby?

Sara and I both wrote pieces about what Crybaby meant to us and sent them to Emy Story, who has been our creative director and collaborator since 2004. The ice cream is her response. This record is about vulnerability — it’s about Sara trying to have a child with her partner, and for me, it was about making decisions, like buying a house and getting a dog, and getting married. And, you know, at times questioning those decisions and questioning: I am a nomadic person; I am free-spirited, and then I feel very caged. But also acknowledging those choices in my life.

This record is about growing up. It’s about kind of letting go of the past. And yet there’s this sort of childhood element to it, this reflection, this nostalgia that we’ve been sort of stuck in for years.

We wrote about all of that, and Emy came back with this concept of ice cream as very much an iconic image [of childhood], but she had this twist about it. She wanted to go out and photograph the ice cream. She went and got an ice cream cone from McDonald’s, and when she came out of the restaurant, she dropped it! She said people came out of nowhere and were like “Oh, no, we’re so sorry that happened to you, and we’ll get you a new ice cream cone!” And she was like, “No, no, this is beautiful.”

She took all these photos of the ice cream cone in the gutter with COVID masks and cigarette butts and all this garbage on the ground, and it summed up the album, you know? It’s growing up and these changes in the pandemic and it’s the childhood thing and the complications of being a queer person and trying to have children and years of hormones and clinics and paperwork, and it just really summed up the complications of that. That photo is what’s on the back of the album. She shot all these other photos of ice cream, [but] instead of sprinkles, it’s push pins with the color tops. Taking in an image that feels really innocent and childlike and then putting a razor blade in it — underneath everything good is like complications and danger. And I just think it’s really beautiful.