In the late 1990s, on one of their earliest tours, the Drive-By Truckers nearly met a grisly fate. After a short stay in Lansing, Michigan–during which the local headliners all had the flu and spent the night puking backstage–the band had to make their way to Buffalo, and not even an hour into the drive they hit a blizzard that lasted the length of Ohio. So these Southern boys white-knuckled their way around Lake Erie, up through Cleveland, and finally into New York State.

“A sane person does not get thrown off that animal and then want to get back on,” said Mike Cooley, decades later when we spoke in a previous interview. “But we couldn’t wait.”

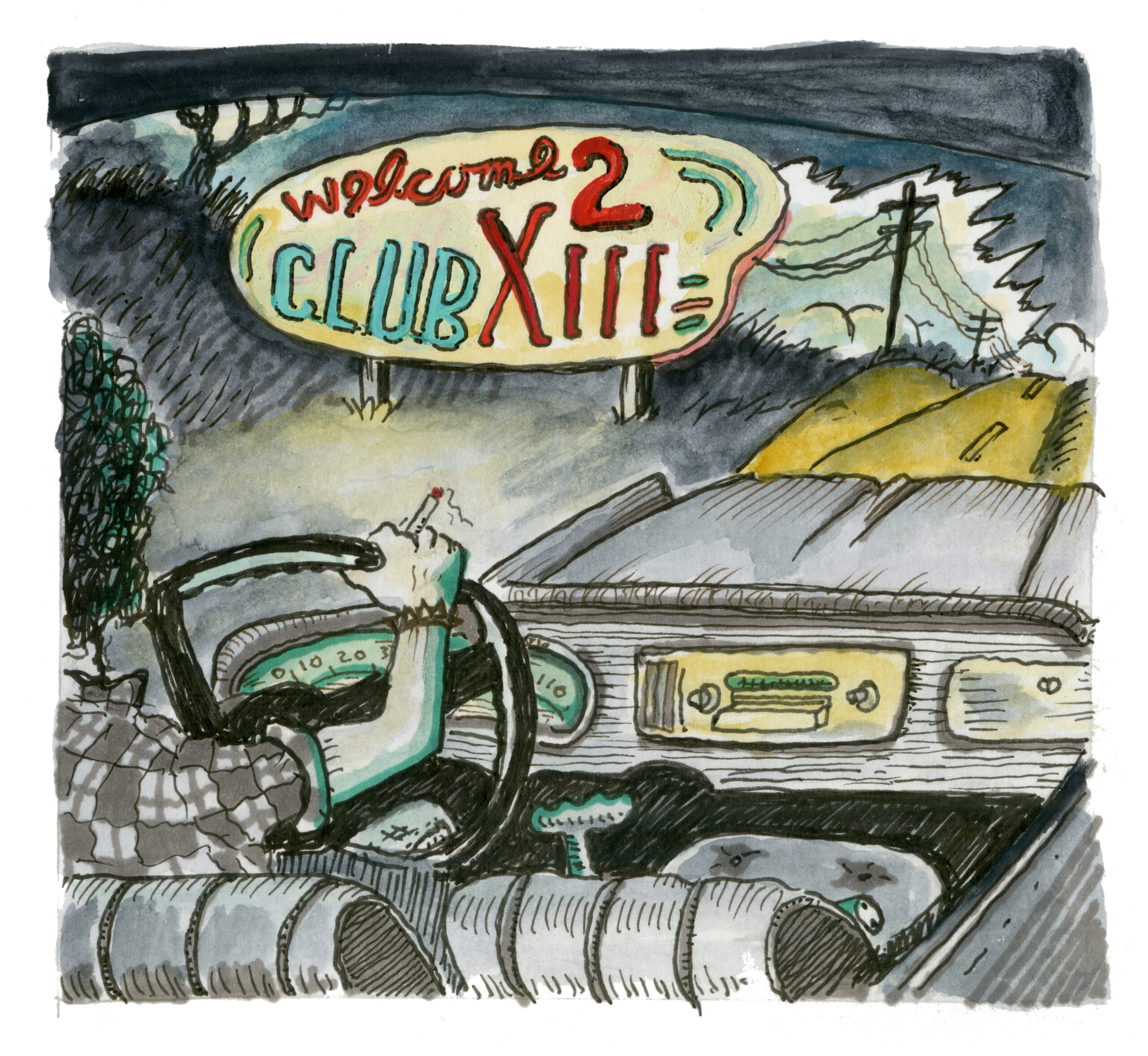

A life of near misses is the subject of their 14th album, Welcome 2 Club XIII. The weirdly wise album takes the band’s history and wonders how they managed to keep it between the ditches for so long. More than 25 years after Patterson Hood convened some friends in Athens, Georgia, to record a few funny, hardscrabble songs about the South, that band is still rolling along, even if only two of the original members remain: Patterson, a gregarious guy nicknamed Sasquatch, and Mike Cooley, cool and quiet, a.k.a. Stroker Ace. Their band has survived its share of hardships, not just bouts of the flu and blizzards but broken-down tour vans, near-constant lineup changes (including the departure of Jason Isbell), fights with record labels, fights with each other, substance abuse, bruises, scars, corrupt presidential administrations, Southern stereotypes, tornados, thunderstorms, even a hurricane. And, as Hood explains in a new song called “The Driver,” they even dodged a meteorite somewhere in Idaho.

Despite every setback, Patterson and Cooley—along with longtime drummer Brad Morgan, multi-instrumentalist Jay Gonzalez, and bassist Matt Patton—understood that they weren’t really cut out for much else, and while a rock and roll lifestyle doesn’t come with benefits or a retirement plan or even that much in the way of a paycheck, it does offer guidance, purpose, and eventually perspective. If they didn’t bounce back stronger from each setback listed above, they at least emerged with greater determination than before, and they’ve been driving long enough to amass one of the most consequential and exciting rock catalogs of this young century, full of albums that changed how we think about the South and about America, songs that found a way to embrace both the beauty of this place and its ugly history. Along the way, they’ve amassed an incredibly tight-knit community of superfans, dubbed Heathens, who follow the band on every tour, parse every song lyric, and see something of themselves in these carefully observed tales of Americans at loose ends.

Also Read

The Best Concerts Of 2023

The Truckers have been on the road long enough to be called survivors, although that word sticks in their craw.“There’s no comfort in survival,” Patterson sings on “Wilder Days” which closes out Club XIII. “But it’s still the best option that I’ve found.” That word suggests that their story is coming to an end, but there’s still a lot of gas left in the tank, as Welcome 2 Club XIII proves. From the superlatively sludgy guitar riff that opens “The Driver” to Patterson’s heart-on-sleeve vocals on the wistful closer “Wilder Days,” the album rocks harder than you might expect from two dads pushing 60. They’re still in the process of surviving, which means these new songs look back on their long history but don’t indulge in kneejerk nostalgia for rock’s heyday. Even when they revel in the memory of a hometown dive—spandex! hairspray! Foghat cover bands!—it’s with more than a little chagrin. They’re not looking to relive their glory days. In fact, the Truckers sound like they’re relieved their glory days are over.

Club XIII was their CBGB’s, their Max’s Kansas City, and it’s arguably just as crucial to the North Alabama music scene of the late ‘80s and early ‘90s as those venues were to New York punk. They haven’t written about that club before, but the Truckers have made themselves—their own history, their band, the trajectory of their career—prominent subjects on nearly every album. Some of their trials and tribulations are acts of God, but many more of them are self-created debacles, products of naivete, stubbornness, or just plain ol’ bad decisions. And most of those mistakes have been commemorated in at least one song in their sprawling catalog. The Truckers write persistently about life on the stage and in the tour van—how it affected their marriages, their families, their own identities as Southern white men, as redneck progressives. They portray rock and roll as a life-and-death undertaking, the stakes unfathomably high.

Their breakout album, 2001’s Southern Rock Opera, a double album they self-released after every label turned them down, is about the “three great Alabama icons”: opportunistically racist governor George Wallace, Crimson Tide football coach Paul “Bear” Bryant, and Lynyrd Skynyrd mastermind Ronnie Van Zant. That’s the album where Patterson coined the phrase “the duality of the Southern thing,” to speak to both the pride and shame he felt about his home, and it may be the most quoted rock lyric of the last 20-odd years. But that album is also about a band called the Drive-By Truckers, and how they saw their own dreams and misgivings reflected in Skynyrd. On closer “Angels & Fuselage,” the opera’s climactic finale, they imagine themselves aboard that sputtering airplane, right alongside Ronnie, as it clipped the trees above that anonymous Mississippi swamp, they were “adding up the cost of these dreams.”

They’re still making those same calculations on Club XIII, but this may be the first time they’ve written about those dreams in the past tense. Middle age offers them a different perspective on their wilder days, and what once looked like acceptable sacrifices now seem like harder losses. There’s a new math on these songs, especially those about friends they’ve lost along the way—to suicide, to depression, to senseless tragedies. “We Will Never Wake You Up in the Morning” eulogizes a fellow musician who drank and drugged himself to death, and it’s alarming how many people fit that bill; it could be about Justin Townes Earle or Jason Molina or even Jason Isbell had he not gotten sober. Yet, it’s a gentler suicide song compared to Patterson’s “Do It Yourself” and Cooley’s “When the Pin Hits the Shell,” both from 2003’s Decoration Day and both inspired by the death of a mutual friend. Those songs are full of anger and confusion and blame, but “Wake You Up” is more sympathetic, more evenhanded. Twenty years will change your outlook.

How did they manage to make it this far? Stubbornness, of course, but also adaptability. The Truckers have been a lot of different bands over the years. They started life as an alt-country band, writing joke songs that reveal very serious undertones as well as a keen understanding of character and story. To make Southern Rock Opera, they transformed themselves into a southern rock band, albeit one with a more complicated relationship to the South itself. When Jason Isbell left the band in 2007, they bore down on their southern-soul bona fides, emphasizing groove and vibe instead of boogie riffs and Wet Willie covers. And just when it seemed like they might get put out to pasture, the Truckers redefined themselves as the self-styled Dance Band of the Resistance, recording some of the most insightful protest songs of the 2010s, not to mention the most righteously vulgar (“Stick it up your ass with your useless thoughts and prayers”).

Now, whenever they hit the stage, the Drive-By Truckers are all of those bands at once. However solid their albums are, they’re first and foremost a killer live act, disregarding the need for rehearsals and setlists so they can fly by the seat of their pants. They keep nearly every song they’ve ever recorded (and many they haven’t) right at their fingertips, so that old favorites collide with new ones, obscure deep cuts bump elbows with fan favorites. Time collapses, so that the band live with their history onstage, constantly replaying and rewriting and reassessing every little thing. The past isn’t past, as the old saying goes. It’s not even past.

By taking this idea from the stage into the studio, Club XIII casts their past in a new light and slyly comments on songs that have come before. That makes it an absolutely essential addition to their catalog, and they sound rejuvenated, almost recklessly inventive in how they write and arrange these songs. It’s tempting to say that this is how rock bands ought to age: not too gracefully. On the other hand, the Truckers find few reassurances and very little consolation in these memories. There’s a peculiar melancholy hanging over these new songs, some sad truth just beyond the fringes of the lyrics and melodies, something just out of reach and therefore all the more haunting. In the past both Patterson and Cooley have sought to order their disorderly world by writing songs, but they’ve learned that a killer riff and a great hook will only get you so far. They’ve stuck around long enough to acknowledge the limits of songwriting, but rather than get frustrated or discouraged, they just keep driving.