Kenny Loggins may forever be associated with his era-defining contributions to the soundtracks for such ’80s classics as Caddyshack, Footloose and Top Gun, but they are just a few of the countless milestones in his eventful, 50-plus-year career in music.

Already a folk-rock superstar by his early 20s as part of the duo Loggins & Messina, the artist went on to inadvertently pioneer yacht rock thanks to his own late ‘70s solo work and a series of hit collaborations with Michael McDonald (“What a Fool Believes,” “This Is It”). He spent the following decade as one of the most commercially successful artists in the world and has rarely stopped working since, dabbling in everything from country, children’s and holiday music and winning new fans at every step of the way thanks to his willingness to poke fun at his bearded, soft rock persona.

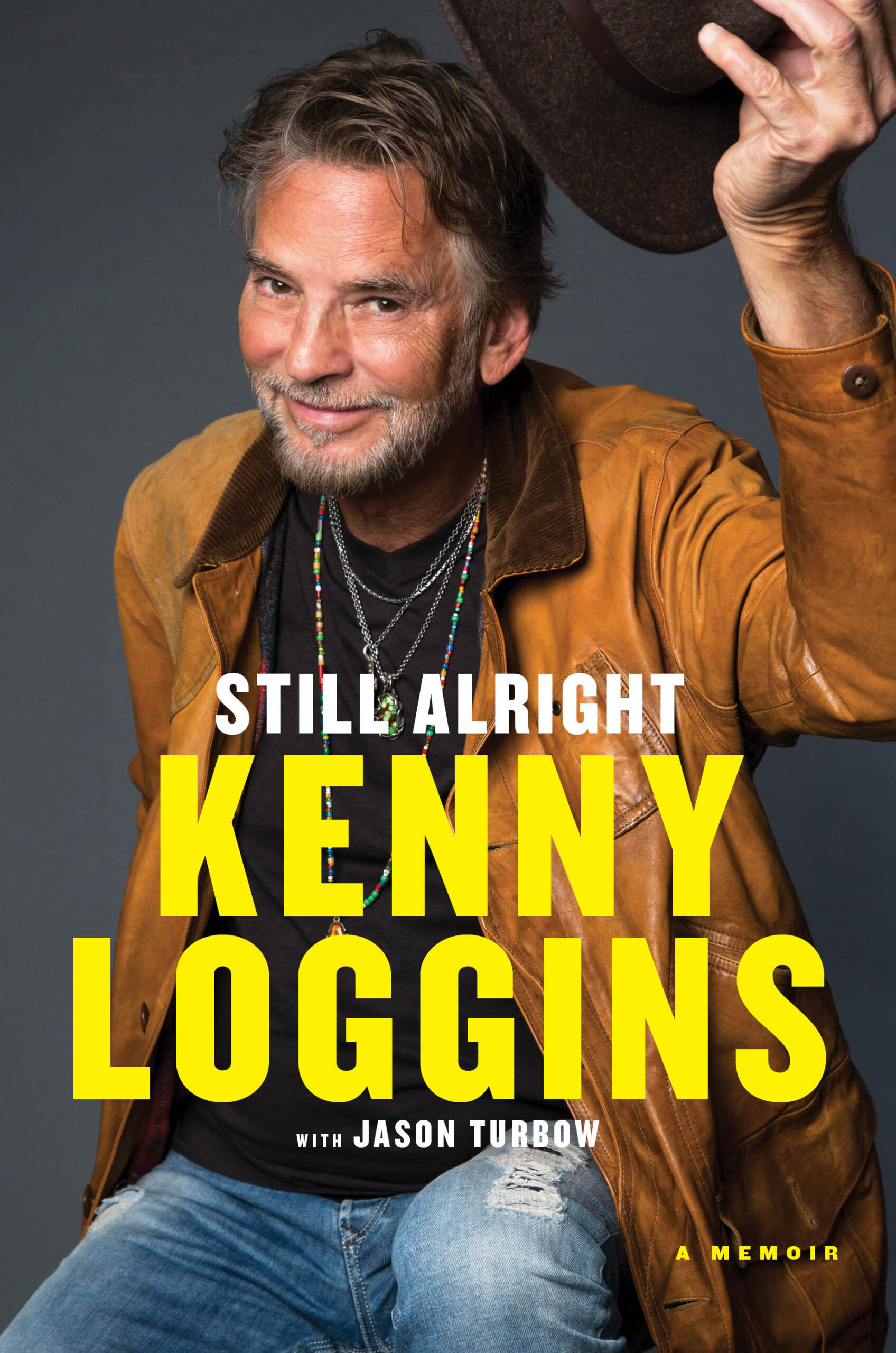

Loggins chronicles all these experiences, as well as his two marriages and divorces and being personally invited to participate in “We Are the World” by Michael Jackson, in the highly entertaining memoir Still Alright, co-written with Jason Turbow and due June 14 from Hachette Books.

Just as the Top Gun sequel Top Gun: Maverick arrives in theaters this week, SPIN spoke to Loggins, 74, over Zoom about suing Garth Brooks for plagiarism, the art of collaboration, the enduring appeal of Top Gun and Footloose and the therapeutic value in smashing aluminum stepladders with a baseball bat. The artist will support Still Alright with a handful of intimate shows this summer, and will also reunite with Jim Messina for two Loggins & Messina performances July 15-16 at the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles.

SPIN: The list of artists you’ve worked with is staggering, but the one that really jumped out for me when reading the book was Will Ackerman, the founder of Windham Hill Records. What about the label’s philosophy and Will’s music specifically spoke to you?

Kenny Loggins: One of the very first spiritual retreats I did was in Palm Desert, and I was working with a Tibetan Buddhist retreat master. She’d take a time out, and I’d hear Windham Hill guitar music coming out of her room. I went into a really deep trance state that was very much alpha, and I’d never had the experience of meditating with sound. I’d always just done it in a quiet space. The guitar music took me to a very deep place, and I was like, “What the fuck is that? I’ve got to have that.” She gave me her cassette and I got turned onto Will in particular through songs like “Bricklayer’s Beautiful Daughter,” which were so melodic and beautiful. I made a note that it was something I wanted to come back to. George Winston and other artists of that era are sort of improvisational but they’ll hang out in a certain passage before moving onto another. They didn’t use the pop song form at all. What we’d traditionally call a verse may only be stated one time. Mostly, each place they step becomes something really memorable. I sort of integrated the idea of longer passages to get out of the verse/bridge/chorus form, and that really influenced my album Leap of Faith.

Another new revelation for me was that you sued Garth Brooks for plagiarizing your song “Conviction of the Heart.” I know you’re not allowed to get into specifics, but what, if anything, did this show you about protecting the value of your own work?

I hope he doesn’t sue me again for mentioning that I sued him [laughs]. Sometimes you just have to draw the line. Garth is infamous for being inspired by other people’s work. He said to me, “Well, I love that song.” What he said to his co-writer was that I came really close on “Conviction of the Heart” and just missed, so he kind of took it and made it what he thought it should have been. In that way, the question of intention became important. Theoretically, when court becomes a part of that process, they’re looking to see what was the intention of the writer. Did they borrow from the original song intentionally, or was there a subconscious thing, where you tap into the music that’s hovering over all of us, and you pull something down? As writers, we’re always taking from what precedes our work. Sometimes it shows up in what we’re writing. It would have been real easy for me in my early days to pull from Elton John, because there was such a strong, melodic structure there, and my voice was more that way then. But in this case with Garth, it was a conscious effort. He told me so. He said “I want something just like this” to his co-writer. That’s why it wound up on the steps of the courthouse.

You worked with absolute legends like Michael McDonald, Stevie Nicks and Michael Jackson when they were at their creative peaks. Were those experiences as fulfilling as the average reader may imagine?

Yes, especially if you have a kinship with the writer and their music like I did with Michael McDonald. I thought I had such a strong sense of his song form that I could kind of become him and think, “Well, where would he go next?” That’s what I did with “What a Fool Believes” when I was standing outside of his house [sings the opening piano melody and McDonald’s first vocal line]. He stopped, and my mind went, “Well, where would he go? He’d go up there. He’d do something above.” I wasn’t so much injecting Kenny Loggins into the tune as thinking I was doing Michael. That’s why him turning down “Whenever I Call You a Friend” was so shocking to me, because I thought I had nailed a Michael melody [sings melody]. No matter who I think I’m doing, whether it’s Tina Turner, Aretha Franklin, Mike McDonald or Steve Winwood, I’m still always being me. But it’s about where I think that artist might have gone. That’s what collaboration is for me. I try to absorb the energy and the vibe of the artist I’m working with. That’s why I was disappointed in myself that I was in such a rush to record Michael Jackson’s voice that I didn’t stop to think, “Wait a minute! He’s a pretty good writer We should just sit down and write something.” I felt like, in my own critique of my work, that I really missed the point with Michael. “Who’s Right, Who’s Wrong” is a really cool song, and Michael was willing to come to the studio and record.

There’s some amazing synergy with the timing of your book release and the arrival of the Top Gun sequel.

It’s blind luck, again!

Did you really record a new version of “Danger Zone” for it?

Yes. I tried to nail it. I tried to be exactly the same except sonically, I was ready to have the guitars come from behind in full 5.1. In the original version, the chorus is two electric guitars. We’ve been trying to figure out who that was, because [the song’s writer] Giorgio [Moroder]’s not around. I think it was Dann Huff, who is now a Nashville stalwart. He was one of my go-to guys in the rock days back in the ‘80s. This time, when the first chorus comes in, I laid in about four guitars to make it more like a Foo Fighter-y kind of thing. It’s sort of like the dream version of what we think “Danger Zone” did back then. “Danger Zone” is almost mono compared to what I can do now with a sound system that wraps completely around you. I knew Tom Cruise was very much in love with the original “Danger Zone,” so I wanted to have that be the essence of the song. I mixed the new version in mono when you hear the drums come in, with four tracks of drums and big reverb. I probably took it too modern and too far for Tom, but what I think Tom wanted to do was re-conjure that original vibe. The only thing that’s really going to do that is to use the original version, so that when the movie starts, people are brought right back to the vibe of the first Top Gun, and then it builds from there.

What will happen with this new version?

I’ll stream it. With “Playing With the Boys,” the director had originally asked me to make it a duet with a female, so I brought in Butterfly Boucher to sing it. I had her arrange it how she would do it, and it’s really cool. It’s much more modern. It doesn’t have that same aggressive, ‘80s stance to it. She added a minor chord in the chorus, which is very cool. We’re streaming that one now, but I need a better way to get it out there. Now that the movie is out, I want those two songs to appear somewhere where people can go, “Oh, look at what he did with it now.”

“Playing With the Boys” from the original Top Gun has become a sort of gay anthem. Was it satisfying that one of your songs took on an unexpected life of its own like this?

Absolutely. In my imagination, the volleyball scene was very secondary to the movie. I didn’t see it as a scene that anyone else would want to write for. Peter Wolf and I and his wife dug in on, “Well, what’s that vibe?” We came up with the line “playing with the boys” and with Peter’s help, we wrote a really strong rock tune. I still perform it live. That was the luck of being in the studio working on “Playing With the Boys” when I got the call to consider an up-tempo song that Giorgio had, which became “Danger Zone.”

Many younger people have been re-introduced to you through things like Archer and your appearance with McDonald on Thundercat’s “Show You the Way.” Is it fun to both give in a bit to the mystique of Kenny Loggins the character while also working with people who are clearly genuine fans?

I have young kids — everything from a 23-year-old to a 40-year-old. They all have different musical tastes. My 29-year-old and my 40-year-old both called me when they heard Thundercat say, “I want to write with Kenny Loggins,” because they are both big fans of his. My kids send me music all the time, because they know I want to absorb whatever they’re into. I have soul music in my DNA and folk and a little bit of country. My daughter is in Austin, and she’s writing what she thinks is alt-country. She’ll send me her influences, and it’s pretty cool stuff. It’s another way of looking at acoustic music. I’ve done a couple of writing camps where I came in to be a mentor. At the end, you end up in a corner with three or four other writers and you try to write something different. It’s really fun for me, because they take me into melodic places where I wouldn’t have gone.

When was the last time you actually watched Footloose?

Mostly what I see is Kevin Bacon’s prom dance. The beauty of that moment is that they were dancing to a facsimile of “Footloose.” We were hoping to get the demo in time so that they could actually dance to that, but we didn’t. So [co-writer] Dean Pitchford pulled a Chuck Berry song and then they VSO’d the tempo to be the tempo of “Footloose.” The whole thing about white people dancing in the movies — they’re not dancing to real songs. They’re just kind of moving back and forth to nothing, so that’s why you see all these white people having no clue what the tempo is, because the real song isn’t dubbed in until later. It perpetuates the mythological truth.

I saw it recently and it was almost wistful to think of a simpler time when music could bind people together so intensely.

I hadn’t seen in that way, but I as I mentioned in the book, Footloose speaks to personal freedom. The song and the movie continue to live on because it triggers that part of us that wants to be free. Dancing becomes a metaphor for freedom.

You wrote the theme song for Caddyshack 2, but be honest — have you ever actually seen the movie?

No [Laughs].

Related question: who would you rather smoke a joint with from the original Caddyshack? Chevy Chase’s Ty Webb or Billy Murray’s Carl Spackler?

One or the other, you mean? That’s a tough question. They’re two radically different people. I think most people would say Bill Murray’s character, because it’s quintessential Bill. But in those days, Chevy Chase’s subtlety in his humor was so hilarious. There’s that one scene in the movie where he’s getting a bottle of water for the girl he’s trying to seduce, and he pours two old ones together. He’s doing that while he’s humming a song and trying to pretend he’s doing something else. His humor was right on the money back then, and I have a feeling it would have been easier for me to relate to that personality. Bill was playing a Vietnam War casualty who was reliving his ‘Nam experience on the gophers.

You talk about the cathartic value in smashing stepladders. I must admit that you bashing away at them with a baseball bat in your garage is a pretty unusual mental image.

That was the evolution of my Fischer-Hoffman psychological work, which was to beat a bag of some kind. Eventually, that evolved into my hanging a heavy bag from the ceiling to hit with a Little League baseball bat, so I wouldn’t throw my back out. During that really intense period of recovering from a shocking divorce, I was beating a bag in the garage, and went from the bag to an aluminum stepladder. When I demolished it, it felt so much better than just hitting a bag. It was like, something’s actually happening with that bat that I can see and feel. So I just went out and bought half-a-dozen ladders.