If the first half of the ‘90s were alt-rock’s boom years — when formerly unknown bands were turning into multi-platinum sensations every few months — then 1996 marked the beginning of its flop era. Weezer’s Pinkerton, though now remembered as a career-defining classic, sold so poorly compared to the band’s triple-platinum 1994 debut that Rivers Cuomo wouldn’t regain the confidence to release another album for nearly five years.

Other acts like Bush, Counting Crows, Gin Blossoms, Sheryl Crow, the Presidents of the United States, Better Than Ezra and Sponge all released their second albums in 1996. And while some still sold respectably, each registered less than half of what their debut sold, according to SoundScan. But it wasn’t just younger bands hitting the dreaded “sophomore slump.” Established bands like Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, Stone Temple Pilots and even beloved alternative trailblazers R.E.M. suddenly found themselves selling a lot less.

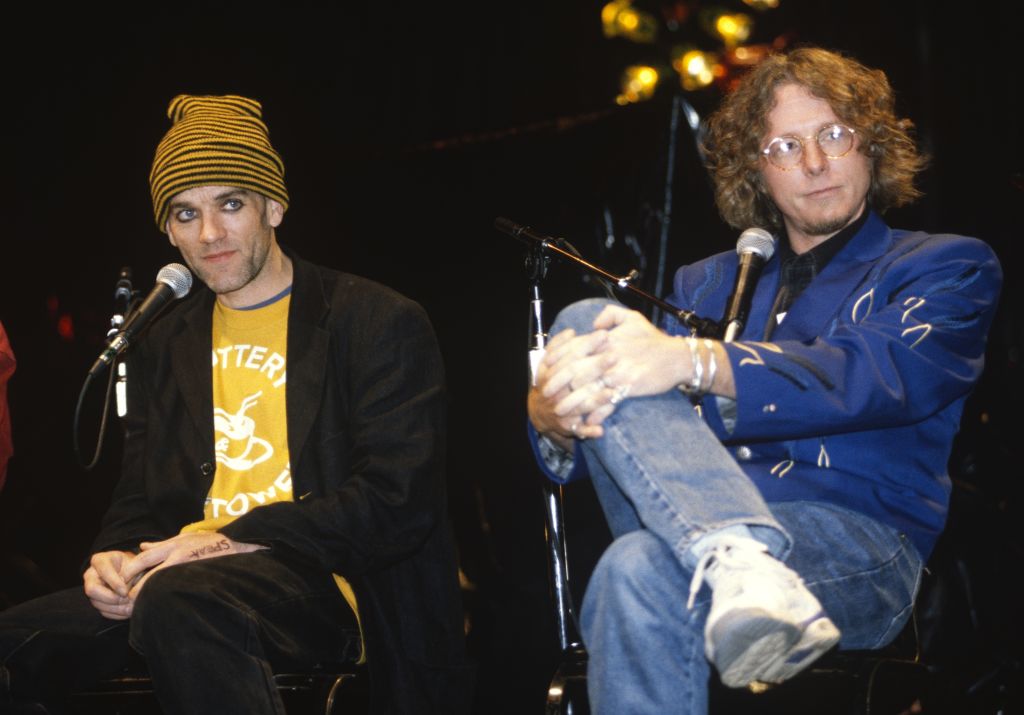

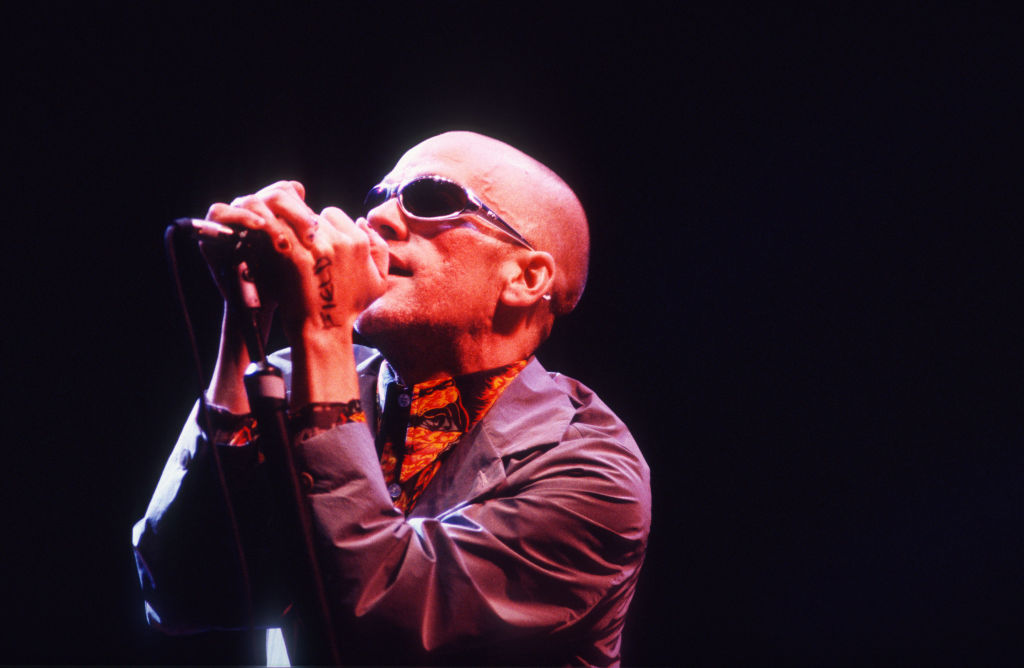

It was that summer when R.E.M. renewed their contract with Warner Bros. for an estimated $80 million, the largest recording contract in history at the time. That such a huge and historic deal was going to an eccentric little quartet from Georgia instead of someone like Madonna or Michael Jackson was a testament to the band’s remarkable decade-long rise — one which mirrored the commercial flowering of the American alternative rock scene they epitomized. Their sales had steadily increased over nine albums, with their last three going quadruple-platinum. So even if the contract’s hefty sum was more of a reward for past performance than a forecast of what was to come, there were presumably optimistic expectations for the band’s future earnings.

The album R.E.M. released in 1996, New Adventures in Hi-Fi, was the final one under the original Warner contract they signed in 1988. It coasted to platinum, but by comparison, its sales had a massive dropoff from their other Warner releases. They didn’t know it at the time, but it would also be the band’s last million-seller in America (although the band’s popularity in Europe held steadier). Shortly thereafter, drummer Bill Berry left the band, and the remaining trio released five more albums – only two of which even went gold – under that massive contract.

Diehard R.E.M. fans who were disappointed by 1994’s divisive Monster were simply getting off the bus for New Adventures in Hi-Fi, although the album developed a good reputation over time. Maybe the offbeat lead single “E-Bow the Letter” (featuring spoken-word verses and a gloomy Patti Smith chorus) scared off casual fans, or it’s possible that R.E.M. were finally just too old and familiar to run the charts anymore. The Cure – another long-running band who’d grown into an unlikely pop phenomenon in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s – also saw their sales drop sharply for 1996’s Wild Mood Swings, although that could be attributed to fans realizing there wasn’t another “Just Like Heaven” or “Friday I’m In Love” on it.

As previously mentioned, several other major rock acts saw their sales cut in half with their 1996 releases as well. Pearl Jam – who were openly uncomfortable with the enormous success of 1991’s Ten – were in the middle of a lengthy process of deliberately winnowing down their audience in the mid-’90s. Still, the eclectic and anxious No Code experienced the biggest drop in sales they’d encounter from one album to the next. Soundgarden disbanded less than a year after Down on the Upside fell well short of Superunknown numbers. Scott Weiland’s tragic struggle with addiction had just begun to derail Stone Temple Pilots, as they were unable to tour heavily in support of their third album, Tiny Music… Songs from the Vatican Gift Shop. Tori Amos reached her highest Billboard peak with Boys for Pele, but without singles on the scale of her previous two albums, she began playing to smaller crowds for the rest of her career. The Cranberries and the Black Crowes had been huge just a couple of years earlier but quickly slipped off the radar.

For many acclaimed middle-tier alt-rock bands, 1996 was their last stab at commercial success. Acts like the Afghan Whigs, Cracker, Porno for Pyros and Ministry struggled to equal the sales or airplay of previous records. They Might Be Giants, Screaming Trees and the Posies left their major labels or were dropped after their 1996 albums. Even being adjacent to alternative rock seemed to no longer be a sales boon for established acts, as alt-friendly classic rockers like Neil Young and Tom Petty’s unexpected second wave of success finally ended with commercial duds in 1996.

Lollapalooza, the traveling alt-rock festival that had changed the touring business in the first half of the ‘90s, was also showing its growing pains. Stung from the lower ticket sales of the 1995 tour that traded on the indie cred of bands like Sonic Youth and Pavement, Lollapalooza ’96 swung hard in the opposite direction with Metallica – who were themselves awkwardly courting different demographics with their shorter haircuts and an alt-rock radio push for “Until It Sleeps.” Metallica seemed too big to fail in 1996, and Load sold millions while topping the Billboard 200 for a month – even if it could never stack up to 1991’s self-titled release (better known as The Black Album), still the highest-selling album of the SoundScan era. But Lollapalooza wasn’t so lucky. The festival went dormant for a few years after 1997, eventually downsizing from a tour to an annual one-off event in Chicago beginning in 2005.

CD sales steadily rose throughout the ‘90s – reaching an all-time high in 1999 – but it wasn’t alternative bands selling in 1996. Hip-hop and R&B were blossoming as a commercial force in the mid-’90s, led by multi-platinum albums by 2Pac, the Fugees, Nas, Outkast, Snoop Dogg and Maxwell. Sure, there were still 1995 albums by Alanis Morrissette, Smashing Pumpkins and No Doubt doing numbers – and the alternative acts that reached career highs in 1996 helped forecast the more eclectic years that would follow. Beck dominated with sampledelic slacker anthems. Rage Against the Machine unleashed fiery rap/rock. Dave Matthews Band busted out jazzy jam rock. And Radiohead’s ascent to art-rock greatness was just around the corner in 1997.

Maybe the cultural malaise that set in after Kurt Cobain’s 1994 death finally caught up to the business in 1996. Nirvana united the many disparate tribes of rock fandom like no other band of their generation, and fans splintered back into smaller subcultures in their absence. Kids who grew up on R.E.M. or Nirvana were going to high school or college and getting into more niche indie label acts like Belle and Sebastian, Tortoise or Sleater-Kinney. Fans of heavier rock moved to ascendant nu-metal and industrial bands like Korn and Marilyn Manson. Alternative radio listeners dashed fitfully between one-hit wonders like Dishwalla, Spacehog and Primitive Radio Gods.

Of course, big tent alternative rock didn’t disappear after 1996. Bands like Green Day, U2 and Red Hot Chili Peppers survived their awkward mid-‘90s transitional period to return with blockbuster albums in the 2000s. But most bands that began to flop in 1996 just kept on playing to a slowly dwindling fanbase of diehards. Except for Weezer. Weezer is still Weezer-ing to this day.