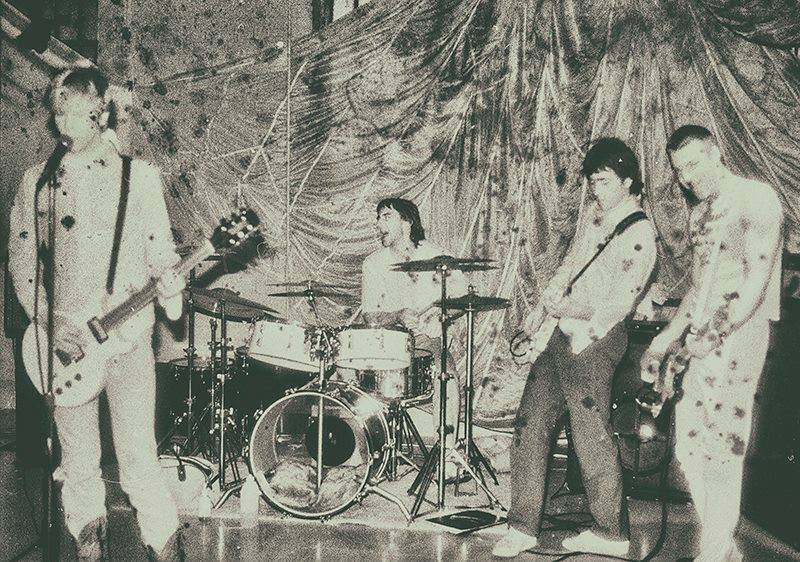

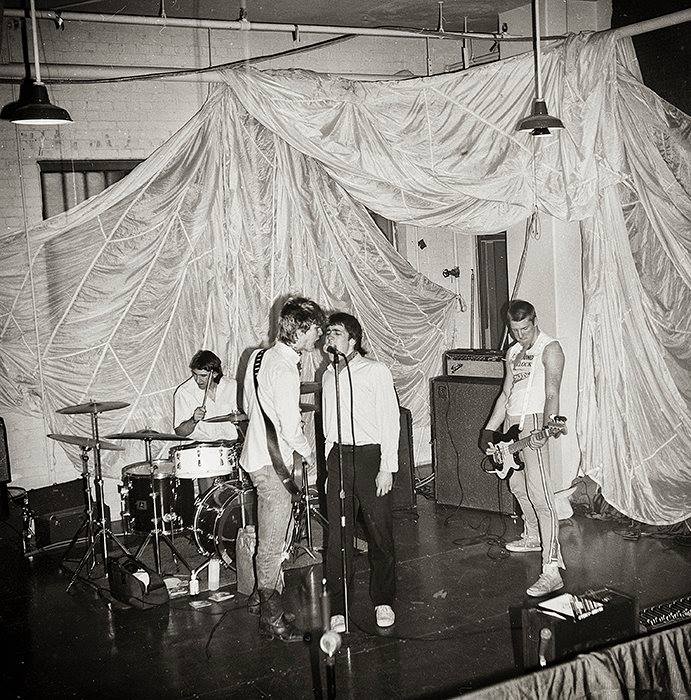

If you haven’t heard of the Living, you’re not alone. The Seattle-based band formed in the early ’80s, recorded some songs in 1982 and that was that. Open and shut case, right? Not when you dig deeper.

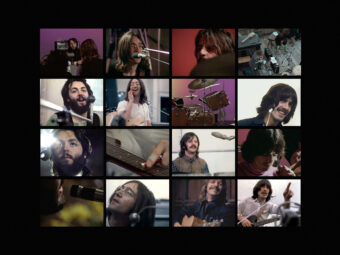

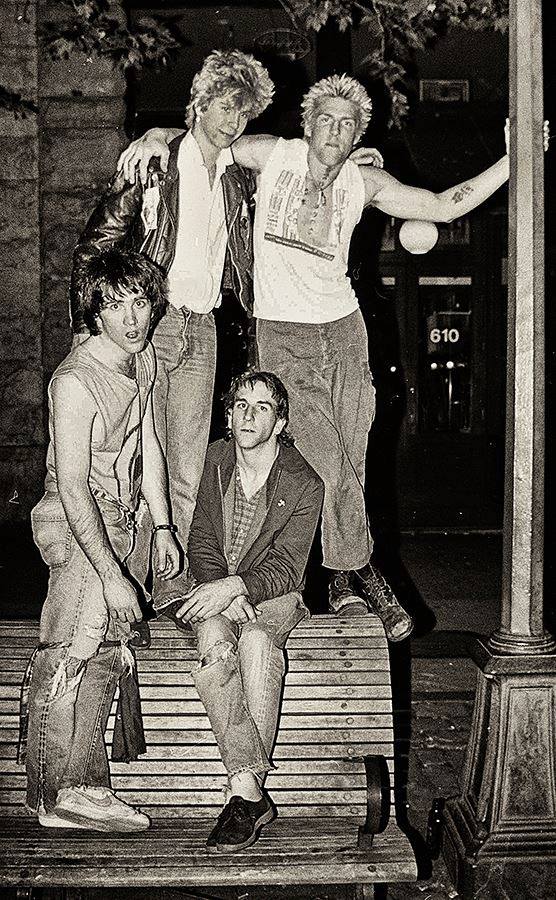

The quartet featured vocalist John Conte, bassist Todd Fleischman, drummer Greg Gilmore and 17-year-old guitarist Duff McKagan, who’d already established himself in the local scene by appearing on 45s by Fastbacks and the Vains.

“The band was really a tight unit of guys,” McKagan remembers. “We had Todd Fleischman on bass, and he could beat up six guys at once, so we had the enforcer. We were really just good friends. When we put out an ad for a drummer, Greg Gilmore answered and came out from Gig Harbour. He opened me up to more prog rock stuff like King Crimson. I went to a King Crimson show with him and took mushrooms, which is highly suggested if you’re into mushrooms!”

In their brief time, they tore it up. The Living opened for DOA, played before intimate crowds, recorded an album and flamed out faster than they formed. Despite missing the Seattle punk and subsequent grunge boom, they had pretty successful music careers — particularly Gilmore, who joined Mother Love Bone, and McKagan, who bounced around locally before ending up in Los Angeles and joining some plucky upstarts called Guns N’ Roses.

Fast forward 39 years, the Living’s only existing recordings are now ready to be unleashed into the world.

“It definitely had been consigned to the box of mementos by most of us,” Gilmore tells SPIN. “We all loved it for sure and thought it was great, but there had never been any serious talk about it turning into a record.”

The process began eight years ago when a friend of the band raised the idea of unearthing a Living album came up with a smaller label. Conti, who possessed the original multitrack masters, had them digitally transferred — retaining the original quality. Gilmore got the files, which led to a slew of potential deals that never came to fruition.

They found the project’s perfect home in September 2020, when Gilmore’s former Mother Love Bone bandmates Stone Gossard and Regan Hagar relaunched their Loosegroove Records.

“I was very surprised when Greg sent me music: ‘How was this never released before?'” Gossard says. “But also that somehow the Living weren’t the legends this record showed them to be. I mean this is one of the most fully realized punk record to come out of Seattle. It has emotion, lyrical diversity, completely authentic punk esthetic and is also very heavy, ambitious and diverse. Duff writing these songs and then the band delivering with the punch they did is magic. How could this record have sat for so long?”

“It’s all for the better probably that nothing worked out until this one because this situation is way bigger than anything I’d hoped for or expected,” Gilmore says.

After the first potential deal had fallen through, Gilmore had been sitting with the mixes and took a crack at himself. As he continued to tinker, the sound continued to improve. “It had been a very long time since I had listened to the mixes that we had we all came away,” he says. “I was really familiar with the sound of it in just every way. It was just very familiar and thrilling to move it into something without really changing it.”

All these years later, hearing the songs brings McKagan back to when he was a pre-fame teenager, but he isn’t necessarily longing for that time.

“I don’t think I feel nostalgic about it, but it brings me back to a frame of mind,” he says. “I don’t think you can feel nostalgia about rock songs and performances that you were a part of. It’s not the same nostalgia as looking at an old team uniform of, like, the Seattle Sonics. This is like you’re still in your body. I happened to write all the lyrics on these songs, which brought me back to a time that was different for me. Facing signing up for the selective service, which is the precursor to the draft that they were threatening to put in there for the ‘war with the Soviet Union’ — that didn’t make sense to me because that would have been a nuclear war.”

That youthful authenticity and innocence — along with the angst and uncertainty of the early ’80s — is reflected in the machine-gun fire of these songs.

In their brief time as the Living, the members learned how to be in a band on the most basic level — and there are no regrets about how things turned out. If you’re expecting a tour, well, it ain’t happening. But at least there’s the music: the document of a band on the brink of a breakout that didn’t pan out.

“There’s no imagined history that any of us can imagine where that [major success] happened,” Gilmore says. “It’s almost comical to imagine the Living as a major touring act. It wasn’t in the cards — we were not organized for that.”

“The Living was my first real step into writing whole songs and bringing them to a band,” McKagan recalls of the process. “It did give me confidence in writing songs because the band did such a good job of making them their own. We went out and played them and people dug it. I still write songs for myself, and if I like ’em that’s good enough. But if someone else likes them, still to this day that’s a surprise, and I go ‘Oh!'”

Revisiting the original tapes all these years later was eye-opening for Gossard.

“When I listen to the Living, I hear elements of all the things I loved about 10 Minute Warning and also elements that became GNR,” Gossard says. “I also hear the type of riffs that influenced me and so many other bands in Seattle. I was affected so heavily in the ’80s by people like Duff and Paul Solger [the Fags, the Fartz, Solger], and I still continue to try and emulate and discover those types of riffs to this day: slinky, groovy, heavy, not too major, not too minor rock and roll.”

“We all thought it was really great,” Gilmore adds. “Any time you’ve just recorded some new stuff, you often think, ‘Well, this is the greatest thing that was ever made,’ and we did think it was really good. You don’t know what something means until years later, when you have some perspective on how it juxtaposes with what else was going on at the time. You can see there was a changing of the guard from the old school to new school.”

Though the Living fizzled out not long after the recording, this once-abandoned album offers the band a deserved legacy that never was.

“I was in so many bands in Seattle before I moved down to L.A. that I’m sure there’s other stuff/recordings that are sitting around,” McKagan says. “You just move on when you’re that young — on to the next thing. But I’m really glad these songs are coming out.”