Thelonious Monk was a misfit, even inside music. The avant-garde jazz pianist had always naturally been the aberrant one, the outsider – an intrinsic aspect of himself reflected through his unorthodox playing in the already virtually boundless space of improvisatory jazz. It was that which didn’t exactly marginalize him but distinguish him as a sui generis musician in a music form already distinguished for its complexity.

Monk belonged to the early jazz coterie that went on to create bebop. Throughout the ‘40s he was playing with such names as Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker; throughout the ‘50s, John Coltrane and Miles Davis. All eventually became known as the first creators of modern jazz. Monk differed from the rest in that he came from the school of stride piano, a sound infused with an echo of ragtime saloon, a conspicuous element in his playing. His particular style though is characterized by its angular quality, abrupt percussive strikes, and the use of dissonant notes he insinuated into consonance (He famously said, “The piano ain’t got no wrong notes!”). It was an inimitably dynamic sound.

His dexterity on the keys compensated for his taciturn tendencies away from the piano. All his inner eloquence was translated into his disjointed melodies that were strangely playful and jaunty compared to other jazz pianists that took on a more somber inflection. His economy of notes lent an elegance his other contemporaries thought they had found in their own breathless slide solos (like the ones you hear when the cartoon cat runs down the stairs) and dependence on legato, two techniques that were in vogue at the time as the standard callsign of taste and talent.

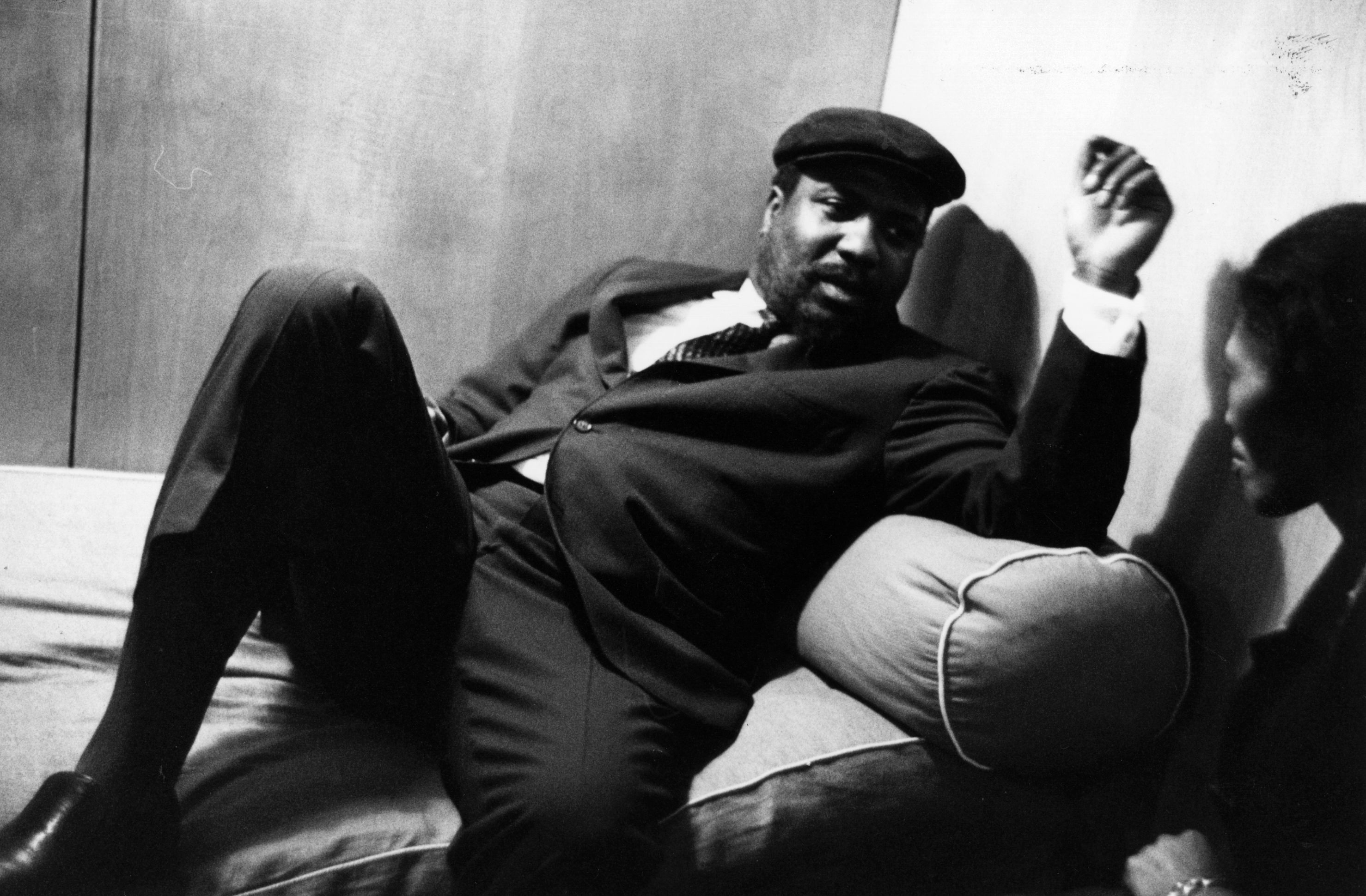

At first, his audiences were apprehensive to his virtuosity that met the critics’ approval first. The public image of him donning a dapper suit, beret, and sunglasses occluded serious consideration into his music. Coupled with his unerring reticence, he was underwritten as a celebrity famed only for his eccentricity. He eventually managed to make it into the mainstream with his placement on Time magazine’s front cover in 1964, jettisoning his former status as an artist on the fringe for national stardom. Then all the due, though dilatory, recognitions were bestowed after years of effortlessly reconfiguring the freeform jazz architecture with his signature use of lacunae and asymmetry.

He went on to be christened as “The High Priest of Bebop” by critics, and before his passing, fellow bebopper Coltrane paid his obeisance to him saying that he felt he “learned from him in every way – through the senses, theoretically, technically.” Four years after his death in 1982, The Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz was erected to encourage the study of jazz for future generations; the so-called monastery where his indelible contribution to jazz continues to influence, and baffle, even beyond his grave.