This interview originally appeared in the April 1994 issue of SPIN.

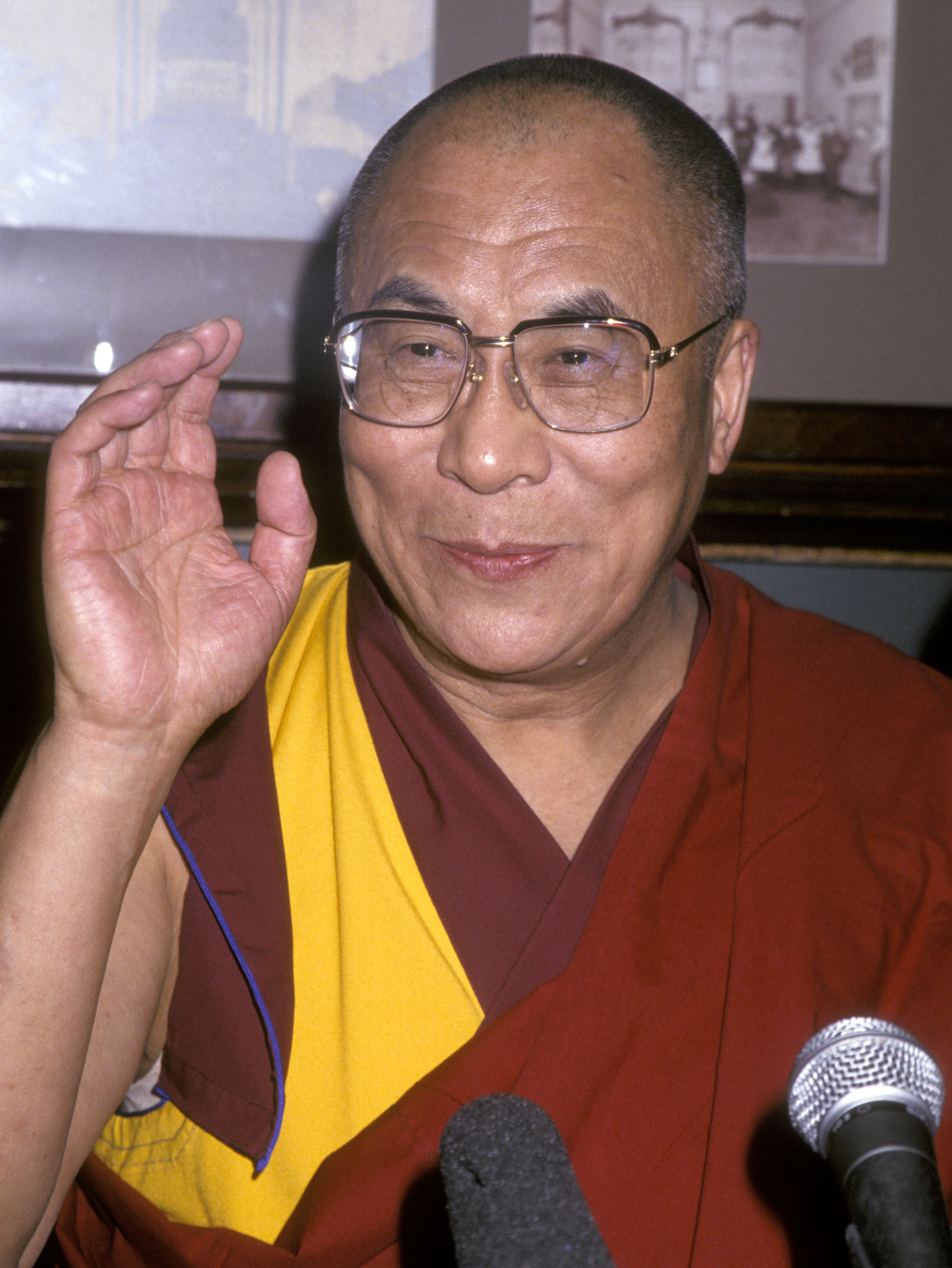

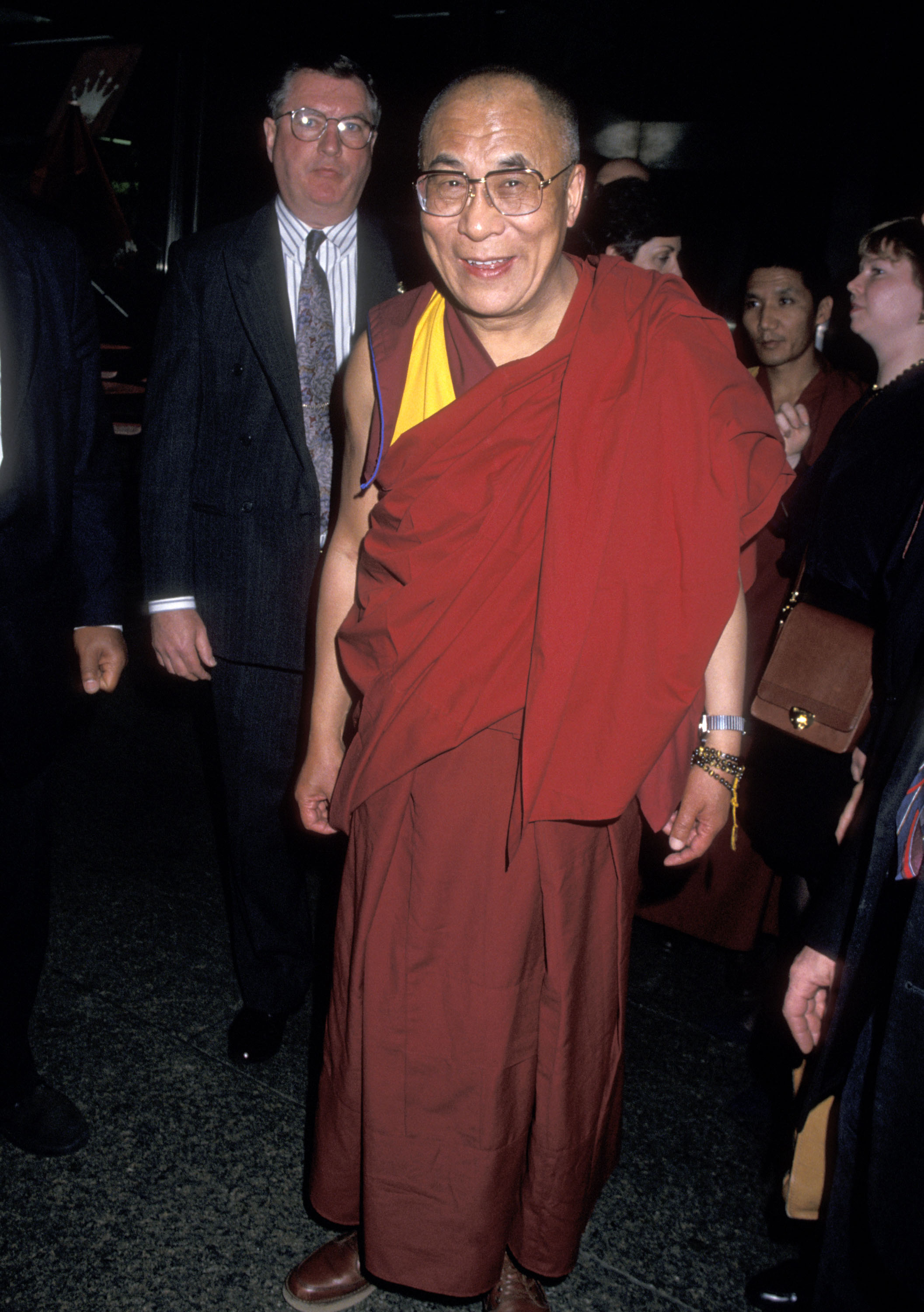

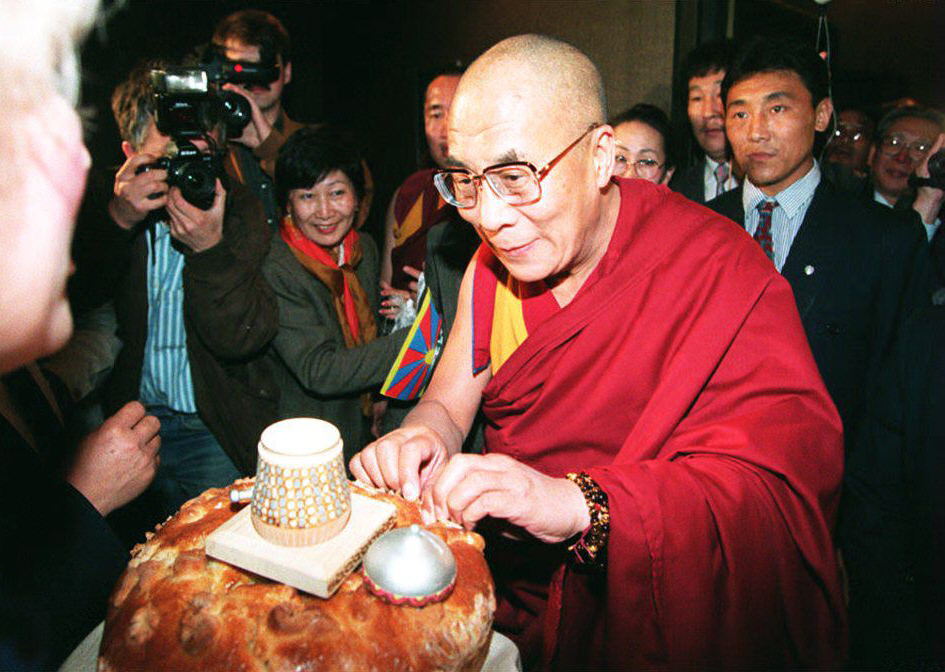

The Dalai Lama, since 1950, has inspired worldwide devotion as the spiritual leader of Tibetan Buddhism and as a political ruler of uncompromising integrity. Dan Reed and Bob Guccione, Jr., journey to India to talk to the 1989 Nobel Peace Prize winner.

When Tibet’s 13th Dalai Lama died in 1933, the Buddhist High Priests, the lamas, went into seclusion to meditate for guidance to find his reincarnated successor. Alongside a great lake outside of Lhasa, Tibet’s capital, a vision came to them of a farmhouse with a blue awning. The lamas scoured the countryside for 18 months and finally, in the eastern village of Amdo, found the place they were looking for. A woman holding a two-year-old child greeted the monk who came to the door, and the child suddenly reached for a string of beads hidden inside the monk’s robes, saying “mine.” The beads had belonged to the 13th Dalai Lama.

To confirm they had found the authentic reincarnation of their spiritual and governmental leader, the head lamas subjected the child to a barrage of tests. The child was shown artifacts that were the Dalai Lama’s along with exact replicas. An adult would have found it impossible to choose the correct one; the child never once failed to. At four, Tenzin Gyatso, son of peasants, became Tibet’s absolute, and absolutely worshiped, spiritual ruler.

Tibet is a country as large as Europe, a vast, high plateaued, virtually unspoiled land that sits in the clouds of the Himalayas like a way station to heaven. Historically it has bordered China, Mongolia (when that was a separate empire), Russia, India, and Nepal; and over the centuries, Tibet kept the Chinese at bay, often only tentatively. But China has always wanted Tibet and in 1950 they took it for good, occupying it by force, suppressing resistance and renaming it as some faceless, meaningless district of China. The rest of the world couldn’t have cared less. The absorption of not only an entire self-governing nation but one of the oldest, intactly preserved traditional cultures was accomplished without a meaningful murmur of protest internationally.

At first, the Tibetans tried to at least cause the Chinese some indigestion, but rebellion was repeatedly put down bloodily. In 1959, a massive popular uprising was quelled and at least 87,000 Tibetans were killed in Lhasa alone. Realizing that the Chinese were interested in not only keeping the land but completely dissolving the Tibetan culture and religion, the Dalai Lama, then 24, and 100,000 Tibetans fled. They eventually settled about 1,900 miles from Lhasa in Dharamsala, India, where the Indian government has allowed them to establish a government in exile.

That’s where, 35 years later, your intrepid reporters come in. Dan Reed, rock musician and student of Buddhism, and I made the torturous journey to Dharamsala from Delhi, a 15-hour drive—which breaks down to 14 hours 30 minutes of pure, unrelieved, and constantly inventive terror on the Indian roads, and 30 minutes of unabashed groveling and toe-kissing of our Indian driver Rattan for getting us there safely—to interview His Holiness, the 14th Dalai Lama. We wanted to talk to him about the ongoing resistance to the Chinese occupation and his hopes to return to a liberated Tibet, and about the role of spirituality and compassion in an increasingly spiritualness and compassionless world. We also wanted to ask him what he thought of Nirvana, but respectfully never posed the trick question.

Laura Lezza/Getty Images

Laura Lezza/Getty Images

We met him on the morning of January 7, a brilliantly sunlit but cold winter day. We had been promised 45 minutes but were granted two hours, as he spoke, in English, in a patient, measured, deep voice. Constantly referring to his interpreter for a key word, he spoke in simple language.

I’ve never spent so little time with a human being and felt the experience so deeply. I know the effect he has gently had on me will stick with me for the rest of my life. Dan said he felt the same way. I think the reason is not just his wisdom, or the uniqueness of who he is and what he represents, mystically and traditionally, but his goodness. He is simply a very good person, unpolluted by hatred or ambition, except to see his country and people free again, and Tibet established as a zone of peace, as he puts it, with that zone to spread across Asia and the world.

There is the very strong likelihood that he will be the last Dalai Lama, that the institution of a theocratic ruler will die with him, either in exile or if he’s returned. He is not daunted by that, in fact postulates the view that that might be for the best, a necessary evolution, a sign of progress. A completion of his, and maybe all of his predecessors’ lives’ mission.

SPIN: You have said in interviews that if Tibet is returned to its people, and its government in exile returns, you do not want to be the political leader, but would rather live out the rest of your life as a monk. Why? And do you think it is possible to not be the political leader?

The Dalai Lama: The main reason why I decided that, when we returned, I should not take any position in the government is that Tibet, like any other nation, must have genuine democracy. So if I were to remain as I had, or if I carried the main responsibility, then, temporarily, people might be happier, but over the long run it would become a hindrance to the genuine development of democracy. Also, people might feel: He will do everything. People will have less of a sense of responsibility. If I’m not there, if all of the responsibility is given to them, they will naturally have a stronger spiritual sense of responsibility.

Then there is the practical reason: I’m nearly 60 years old, so I consider for the next 20 years, I can be active. After that, I’m too old—that’s quite natural. So, a healthy democratic system must develop within the next 20 years.

But what about democracy mixed in with what you are doing now, government run by the spiritual leader?

In any system, there are good points and bad points, bad parts or good parts. The past system [with the Dalai Lama ruling] —there were some good parts, but this is largely dependent on the person’s motivation. In democracy, of course, there are also some negative things, but generally, in the democratic system, the genuinely elected person must take into consideration the genuine public interest. In comparing these two systems, I believe that the democratic is better. Now, with both cases, I think the ultimate factor is what I call circular moral ethics, be honest and more compassionate toward your neighbor, your friend. This includes the environment, animals, the whole society, to be embodied through education, through media, through spiritual leaders, through politicians, through various people. The whole society can be more peaceful, educated. All these systems can be good ones, if the society is moral. If the education of the society declines, then all different systems might not work properly.

Is that the moral responsibility of any government: to be more ethical and educate the people?

Politics is very rarely spiritual. We must develop or build a very healthy society. Then politicians who come from that society will be more honest, more genuine. The society can be more constructive. Of course, in order to build that society, government has a great responsibility, and the media. And also each family, of course, has a great responsibility.

In most of the West, that responsibility is ignored and people are lazy spiritually and morally. Do you feel that can be changed?

I know people who say today, politically, in the West, we are facing some kind of moral crisis. My basic belief, no matter how serious any problem humanity faces, is that the difficulty is essentially a man-made problem. That problem —no matter how serious ideological—humanity has the ability to solve or to change.

Do you think man is inherently good, and succumbs to evil, or man is balanced between good and evil equally?

I believe the answer is more neutral. I’m always telling people, basic human nature is gentleness, human affection. So if human affection is actually the foundation or the basis of human existence — right at the beginning of our life until our death, the rule of human affection is very, very powerful—the more compassionate, more affectionate person is naturally healthier: physically healthier, mentally healthier, and happier. Your comment about balance is also very true. Now, if we ask, “Is this person good or bad?” the answer, I think, is the person can be good, can be bad, or can be indifferent. From that angle, basic human nature, the basic human being, is something good, but can either be good or bad. What is the main factor of good and bad? It’s not your face, not money, but rather, a part of mind, a part of thought. We make a distinction, good or bad. In terms of thought, there are negative thoughts such as hatred, jealousy, fear; they are called negative because these thoughts bring us disaster, destroy our happiness, destroy our future, destroy our family, and eventually destroy our world. With nuclear weapons, we have the potential to destroy the whole world. Nobody is utilizing nuclear weapons with a happy mood. There is a lot of frustration, hatred.

Human affection gives us peace of mind; this is positive because this makes not only us happy, but also brings happier days in our family, in our society. Therefore, we call this positive. In each individual human being, there are both qualities: negative and positive. But human intelligence, if we are thinking properly, thinking fully, allows us the capacity to realize that these negative thoughts are negative and also realize the positive things. Human beings have the ability to increase positive thought and reduce negative thought. Therefore, the conclusion is that the human being, basically, is positive, because of human intelligence and human compassion. Combine these two things, and in spite of the negative things which are also part of human life, they are more dominant. From that viewpoint, the human being is positive.

Why do we have evil? The Buddhist teaching would seem to make so much sense—to be affectionate, to show compassion—and yet it doesn’t work that way. People take rather than give, are aggressive rather than compassionate.

Impatience—we need something immediately. If you give away something, then, for that moment, you have lost something. But if you wait one month or one year, you will receive. If it’s a hundred dollars, there’s a possibility you may get a thousand dollars. But you need more patience.

And even, if you give others more friendship, oh, they will respond to you with a genuine smile. Even if it’s just a mere smile, obviously they give us some kind of satisfaction.

And then also, these are interdependent: the environment, many things involved, including media. I think with television—there is too much violence, too much sex, and money scandals, and advertising. These are helping or influencing your greed or desire. If there is nothing else which can balance this, then day by day, year by year, that thinking becomes part of your life.

I read about a drug for cancer that for one treatment you have to cut down three trees. And the person might need numerous treatments. Is that kind of environmental destruction justifiable for prolonging a life?

That is difficult to say. I can answer both yes and no. Death is also part of our life—we have to go, that’s human nature. But it is also dependent on what kind of person, what kind of life is saved. That’s also a serious consideration.

Your Holiness, what role does ambition play in the spiritually healthy person? Is the ambition to work hard, to create and build, always at conflict with spiritual wholeness?

Such determination, such desire, is not necessarily negative. In fact, for example, one Buddhist principle is the importance of practicing determination in order to serve all sentient beings. So that desire, that determination looks like great ambition. But the main motivation is not to use the thing selfishly, you see, but to serve others. Without such positive ambition, there is no way to proceed.

And also, I think we have to make differences. Amount of desire: There are positive desires and negative desires. Even with anger, there can be positive and negative, and also, there can be positive and negative competition. All of these are dependent on the motivation: Is the person thinking in terms of serving or helping others?

How great is the power of prayer, and how limited?

Prayer has different meanings, according to different religious traditions, religious philosophies. Since Buddhism does not accept the Creator, it places great emphasis on the importance of one’s own actions, so here, the use of prayer means to appeal to a higher, more enlightened being. We believe they have some extra energy. We appeal to them in order to receive some blessing from them. But at the same time, the main factor, we believe, is karma, our own action. So we must be making effort; prayer alone is very limited, its effects are very limited. Our own effort, our own action, is the key factor.

Mahatma Gandhi said that we are not God, but we are of God, just as one drop of water is of the ocean. And I was wondering, you don’t believe in a Creator, but what is your vision of God. Is It our actions?

The English word “God” somehow has a fixed meaning. But if you take a different interpretation, according to one’s own suitability, then of course, God in a sense is ultimate reality, ultimate truth. We can accept that. But if Gandhi says this —I don’t know. One is the ancient Indian philosophy, non-Buddhist philosophy. It believed the soul was the soul of Brahma, something universal.

For me, it is just individual identity. The importance of the individual. That’s Buddhism. So, finally, this individual will remain forever. Buddhists do not believe the individual eventually loses direction.

If there is an end of the world, what happens to the reincarnated soul when there is no longer a physical world?

Oh, there are other planets, plenty of other worlds, that’s what we believe. Limitless worlds.

Can you in your heart love the Chinese and forgive them for their atrocities toward your people?

If we utilize the human intellect, we can make many distinctions, categories. The Chinese, as human beings, are sentient beings; and furthermore, of course, they also want happiness, they also have the right to be happy. As neighbors, and in the future, we have to live side by side. So, in order to have a happy future, to live harmoniously in the spirit of good neighborhood, we must cultivate a basis of that—that is human compassion, human love. If we love the Chinese, they will alter their response. If we maintain hatred, but expect something good from them, it’s impossible. So that’s one aspect. I do believe that. And in my daily prayer, I always pray for the Chinese, to reduce their anger, reduce their ignorance, reduce their hatred. They have some negative ambitions that must go away. And our ambition—that zone of peace —is reasonable and logical. So our ambition is positive. Their ambition is a little bit negative.

In the meantime, it is their atrocity and their cruelty we cannot forgive—we must accept and realize these are negative. This must change, they must go. We have to have resistance about that.

Within me there is some negative feeling, negative desire. This does not mean that I hate myself. We are one being, but within that being there are so many different thoughts and so many

actions. Some actions and thoughts are negative and harmful—this I must check, ultimately, for my own benefit. The Chinese must do the same. As beings, of course, they are nice; you must respect them, must love them. Meantime, their actions, some of their motivation, you must oppose. So once we oppose the Chinese action, Chinese motivation, this doesn’t mean we are opposing the Chinese. When I oppose some of my thoughts, some of my actions, I am not opposing myself.

Is nonviolence really a feasible strategy in this day and age?

I think so. I think so.

Why?

Firstly, now the world is too interdependent: economically, or in terms of education, even from the viewpoint of tourism. Friendliness is a very important factor, and today, warfare is really too much of a danger. The power of destruction is unlimited. So therefore, in spite of failure, everywhere, you always see peace and negotiation, negotiation, dialogue. I think humanity has learned many experiences this century. We are making some kind of conclusions: Warfare is something really destructive, so we must find some other alternative.

And also, I think, in reality, there’s no clear-cut black and white. If it really was clear-cut, positive or negative, then to use destructive force to eliminate the negative perhaps would have some logic. But in reality, everything is mixed. Your neighbor is something like your leg, so if you destroy that, you destroy your own leg. If your enemy is completely separate, has no connection with you, then you can eliminate him, but today I think this has completely changed.

It’s difficult for Americans to identify with the Buddhist philosophy of compassion and nonviolence because our society is so violent. How do you reconcile your philosophy with our reality?

My basic belief is that when we see someone facing suffering, usually we show some kind of kindness, some kind of concern. If there is some possibility to help, we do. If we see an animal in pain, we try to remove that pain —

Only if we don’t fear the animal. If we fear the animal, we leave it alone.

[Considers this, then laughs] That is a good argument! A tiger or a mad elephant, maybe you leave alone!

Again, I think, compassion does not mean you volunteer to take your risk, but, when we meet a stranger, we don’t know whether there is a basis for fear or not, at the beginning. First you should create a positive atmosphere, then see their reaction. If you see there is something negative, then of course you have the right to take precautions. But unless you create the positive atmosphere, you can’t judge if something is negative or positive.

In ’62, when the Chinese started to fight India, the former president of India, a very great person, expressed that India must unilaterally disarm. Then the next day, Nehru, at that point still the prime minister, said, “That’s impractical, unrealistic.” And I felt both are true —the prime minister’s expression is true and practical because of the present circumstances; the former president’s expression is absolutely true, for the longer range.

We must make very clear that hatred is always a troublemaker and negative, dangerous; on the other hand, compassion, patience, tolerance—these are deep human values, real, precious things.

Do you have any memories of the experiences of the other Dalai Lamas?

When I was young —about two or three years old — I expressed some quite clear memory about a past life. Since then, in dreams sometimes, a little bit strange dreams sometimes… but otherwise, I have no such memory. In dreams I met the fifth Dalai Lama and the seventh Dalai Lama.

What happened in the dream?

Well, some conversation. Not always meaningful conversations, just conversations.

If there is a continuation of the spirit, the reincarnated spirit, is there one many-centuries-long plan that each incarnation furthers, a plan from the beginning to the end? And if so, would that mean that the Chinese occupation was meant to be, and actually has a purpose, in this one long plan?

From the histories of the last few centuries of Tibet, I got the impression that the fifth Dalai Lama made a master plan, and, after his death, the sixth Dalai Lama acted according to the fifth Dalai Lama’s master plan. After the sixth—the seventh Dalai Lama onward —there were many difficulties. The Dalai Lama’s government eventually became weaker, weaker, weaker. The Dalai Lama’s position, or the Dalai Lama’s institution, became weak because when the previous Dalai Lamas died, the next Dalai Lama still was very young. And the region became weak, so the Chinese’s influence increased. That master plan failed. Then the seventh Dalai Lama was a completely different type of person, completely devoted in spiritual life; so an alternative spiritual plan was built up. Then the 13th Dalai Lama also, in his early age, had some kind of, perhaps not master plan, but at least some semi- master plan, which, because his government officials did not care for it properly, went wrong. It was a failure of these government officials in the face of Chinese aggression. I am very, very hopeful that in the next 20 years, things may change.

What is your master plan?

I have no master plan.

Your Holiness, has any good come from the suffering of the Tibetan people in the last 40 years?

I think so. And anyway, our suffering already happened, so sometimes it is useful to look at it from that angle. Now, because we lost our own country, about a hundred thousand refugees have come out, come outside, including some special masters or learned persons. As a result, I personally had a new opportunity, meeting with other people. As far as religion is concerned, I met people from different religious traditions, and this has been very helpful to me. Also this gave the world an opportunity to study a variety of Tibetan special things and Tibetan culture. And inside, because of this suffering, Tibet is more united, closer. Tibet should be created as a zone of peace. If Tibet can be a zone of peace, then it could spread toward China, toward India. This heightens the step for demilitarization globally.

What is your hope for the Chinese immigrants, once Tibet is free? There are seven million Chinese there.

Basically, those Chinese who respect Tibetan culture, Tibetan Buddhism, perhaps —if the number is limited, manageable—they can stay.

Why is celibacy important to you? You have said that you do get sexual desires. Why do you resist them?

The main purpose of Buddhist practice is to achieve liberation from your emotions — negative emotions, mainly anger, hatred, desire, and attachment. Now of the many attachments or desires, the most forceful is sexual desire.

By controlling sexual desires, all other desire- negative desire—step by step, is controlled. So celibacy becomes important.

Your Holiness, what is the meaning of life?

If we ask, “Why have we come, why this human being, why has this planet happened?”—this is too complicated. Forget about it. It’s not much use to analyze these things. Of course, each different religious tradition has some different explanation according to different positive philosophies or traditions. I believe the purpose of our life is happiness. This is my basis. We don’t know why this life happens, this is too mysterious. But on the obvious level, I know that my life must be a happy life. If there is no more happiness, then I might lose my hope; then automatically, my life is shortened. In the worse case, I commit suicide. So therefore, life is based on hope. Hope means something good. For these reasons, we can see the purpose of our life is happiness.