This article originally appeared in the May 1986 issue of SPIN.

“Huge brains, small necks, weak muscles, and fat wallets—these are the dominant characteristics of the ’80s—the generation of swine.”

—Hunter S. Thompson

That’s the way Hunter Thompson sees the pursuers of Ronald Reagan’s American dream—a collage of funless, greedy little people in a dollar-bill-green world. The above is from his San Francisco Examiner column, soon to become nationally syndicated.

The quintessential outlaw journalist is back in hot print. His welcome was splashed all over San Francisco with eight-column, page-one plugs over the newspaper’s masthead and TV blurbs in which he starred personally. Even the competition was intrigued. Peter Anderson, of the nearby Marin County Journal, wrote:

“The man who writes best-sellers like Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, whose ideal breakfast consists of omelets stuffed with psychedelic mushrooms, a dozen beers, six Bloody Marys, and a reefer to be named later, sounds to me like, well, an ideal columnist.”

The competition can make small talk about Thompson’s lifestyle, but if he gets off his ass, they better shape up. He’s a damn good reporter who writes in a perverse orbit of his own, leading you down weird paths strewn with fools and scamps.

His outrageous style and disdain for the establishment was “discovered” in the late ’60s and his following grew as he kept turning out best-sellers and scintillating magazine articles. He started out as a tame, orthodox reporter for the National Observer, but the pace was too slow, and he set out to do a book on the Hell’s Angels. The bike outlaws didn’t just chase him off, they kicked the shit out of him first, but he did the book, and it was his first big winner.

Thompson found his niche with the new-wave publications in the mid-’60s, where his outrageous style was stamped gonzo journalism. First he wrote for Scanlan’s and then moved over to the then budding Rolling Stone. Once he got in the groove, he batted out two more best-sellers, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas and Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72. The Great Shark Hunt, a compilation of his works, was his best best-seller.

When his output slowed down, he forged a link with the new generation in the late ’70s and ’80s through his college lecture tours. The stories of his preposterous lifestyle became an introduction to his work for many of the uninitiated, but the legend is no longer enough for them. They’re hungry for more product, and they want to know what he’s been up to.

Only Hunter Thompson knows what Hunter Thompson has been up to, so if you seek the answer, you must go to the mountain, literally—outside Aspen, Colorado, where Hunter lives. But there is a slight problem here. Visitors are not welcome and he despises interviews.

I call Thompson and tell him I’d like to do a piece on him. In reply I hear heavy breathing, but no words, and it wouldn’t take a psychologist to tell he isn’t crazy about the idea. Finally he says, “Well…uh…I don’t know.” More silence, then he says, “I haven’t seen you in a long while. Yeah, maybe it will be fun.”

As the shuttle plane taking me from Denver to Aspen skirts the snow-crested Rockies, I wonder what the hell I’m doing up here. Thompson didn’t answer any of my four calls to confirm my visit. This crazy bastard could just as well be in Mozambique or Katmandu, but when I register at the Inn of Aspen an hour later, the desk clerk tells me, “Dr. Thompson left word he’ll meet you here for dinner.”

I wait in the room for two hours. No Thompson. I head for the hotel lobby, and as I’m walking down the hall I see this figure coming towards me. He’s solidly built, erect, square-jawed, wearing a heavy windbreaker and a baseball cap pulled down over dark shades that deny eye contact. He looks like Central Casting’s version of a CIA guy on the prowl, but it’s Dr. Thompson himself, the least likely candidate for such a role.

As the gap between us narrows, he starts apologizing for I don’t know what, because I can’t understand what the hell he’s saying. Now I know the night is wasted. It’s obvious that Dr. Thompson has already made his day sampling spirits and ambrosias.

It’s tough enough to understand Thompson’s machine-gun delivery when he’s straight, but when he’s on full throttle he sounds like he’s talking in Morse code, and tonight he’s on full throttle.

Maria Khan, Thompson’s associate, joins us at dinner. She is a cool, intelligent, beautiful young lady who tries to separate sanity from chaos. Hunter keeps babbling on. Finally he realizes I’m not interpreting his high-velocity chatter and he slows up.

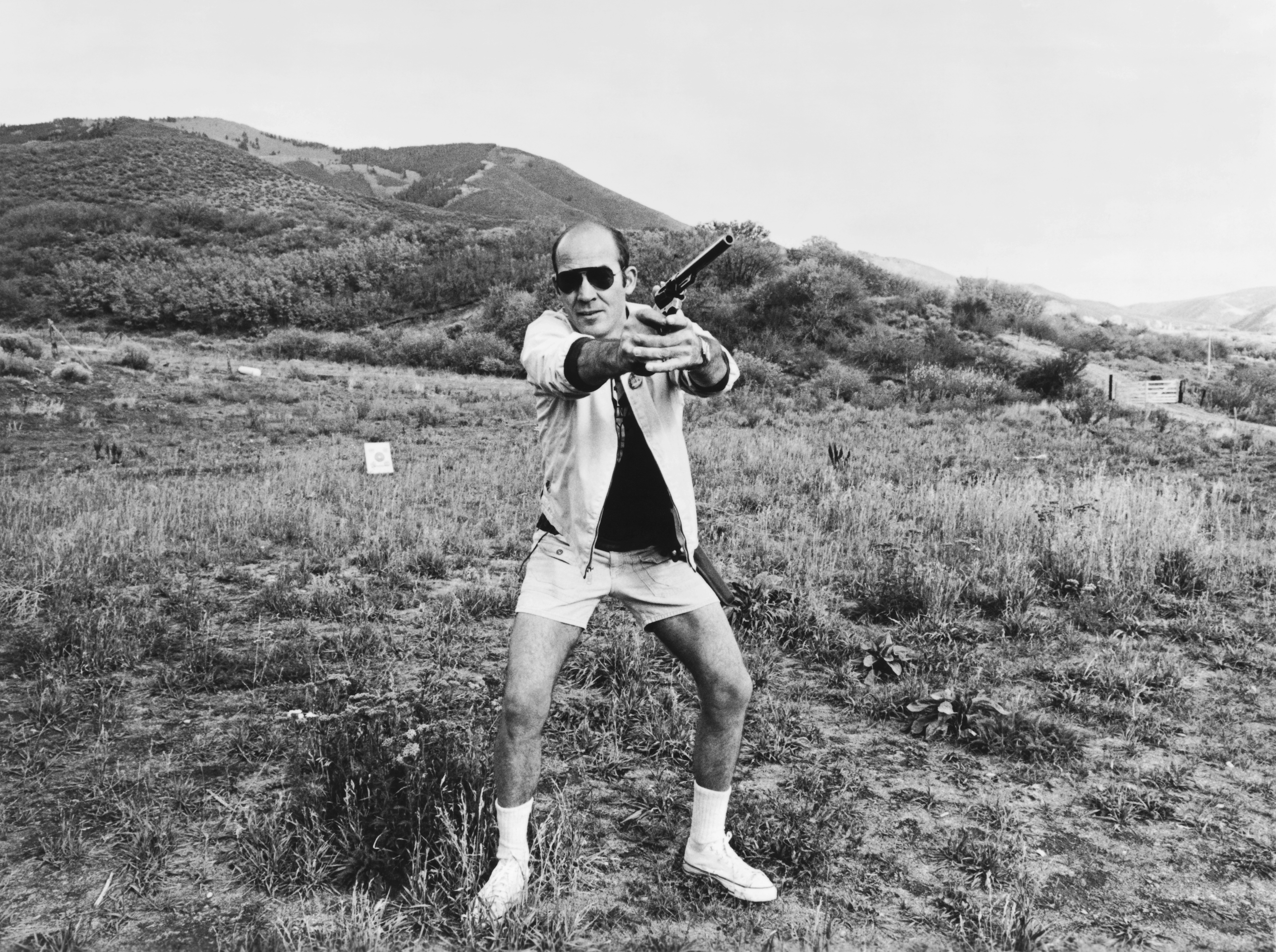

Now I see he has something important on his mind. He reaches into a shopping bag, pulls out a poster, unfolds it with some difficulty, then points to the photo in the center. It’s a picture of Thompson when he ran for sheriff of Pitkin County many years ago. Below the picture a caption reads, “Would you sell this man peyote?”

It’s a funny picture—weird-funny. His head is completely shaved, his face has a pallor, and although he is wearing the obligatory dark shades, you know those eyes are seeing pictures in another world. He looked like a stoned alien who has been left behind by the mother ship. I laugh at the picture. Hunter bristles, then points to it again. “Has to be on the cover,” he says.

“Cover? What cover?” I ask.

“The cover of SPIN. No cover, no story.”

“For a second I think he’s putting me on. He leans back and quaffs the Bloody Mary. He is now behind a panoply of glass and spirits in full color: a double Bloody Mary in tomato-red, two Heineken soldiers in dark green, and a margarita, opaque in the light, the glass rimmed in salty snow.

He sips the margarita, then takes three small pieces of notepaper out of his pocket and tosses them on the table. “It’s all there,” he says. The notepaper is marked pages 1, 2, and 3. The writing is barely legible, but I get the drift. It’s instructions on how to handle the picture.

Now I know he’s serious. I see I’m going to have to play the game. I say, “I don’t know whether this can work. I don’t have much lead time.”

“Then you better get the picture to New York right away,” he answers. “There’s a Federal Express agency at the desk.”

I see I have no other option. “OK,” I lie. “It will be taken care of.”

Now he’s all business. He leans forward in his chair. “What have you got in mind for this story?”

“I’d like to do a piece on you up at your house, your workbench,” I tell him.

He holds up his hand, palm out, like an Indian chief about to make a benediction, then says, “My good friend Harold Conrad, he may visit my house, can stay six weeks if he wants, or as long as he likes…Harold Conrad the journalist is barred.” Then he dives into a second helping of chocolate seven-layer cake, irrigated with chartreuse.

It’s several hours after dinnertime when Hunter starts back to his mountain. Maria, lagging behind, stops to say, “Don’t worry, everything will work out. I’ll see that he calls you around 1 tomorrow.”

Maria calls a little after noon the next day. “Hunter’s embarrassed about last night. I’m sorry about this confusion. We’ll meet for breakfast at the Woody Creek Tavern around 1:30. Taxi drivers know the place.”

I had been warned about renting a car. They’re not safely equipped for some of the more hazardous, icy roads. A wrong slide and you’re over and down a thousand-foot precipice. But the taxis have four-wheel drives and are as tenacious as mountain goats. I wondered how the hell Hunter, who drives as though he is on the Indianapolis Speedway no matter where he is, made it safely on these treacherous roads over the years. I’m sure he rides with the devil.

Thompson’s mystery house is high above the hamlet of Woody Creek, which is in a gully below, some 10 miles from the glitz of Aspen. It has two storefronts—a post office and the tavern—adjoining each other, and that’s it for the business end of Woody Creek. There are spells when this town is Hunter’s only link with the living.

Woody Creek Tavern is a comfortable place that smells of good home cooking. It has a bar, a jukebox, and a dozen tables. The walls are covered with pictures, postcards, and newspaper clippings, mostly of local interest.

I find one clipping interesting. It is a column about a Denver television crew that hung around the Tavern for two days, waiting to catch Thompson on film. In despair they searched out and found his house, but were chased off the property by Hunter, the once-almost-sheriff of Pitkin County.

It’s now 2:30. He’s an hour late. I call his house. The service answers. “No, Mr. Thompson is not picking up.” Mike, the guy behind the bar, says, “You can’t put the clock on Hunter. If he says he’ll be here, he’ll be here.” But Mike doesn’t understand about editorial deadlines.

It’s now 3 o’clock. I call a taxi and start out for Hunter’s house. Ask a native how to get to Thomson’s and he’ll ask how well you know him, then, no matter what you say, he’ll give you the wrong directions. But I got a map from Terry McDonell, an editor and mutual friend of Hunter’s and mine, before I left New York.

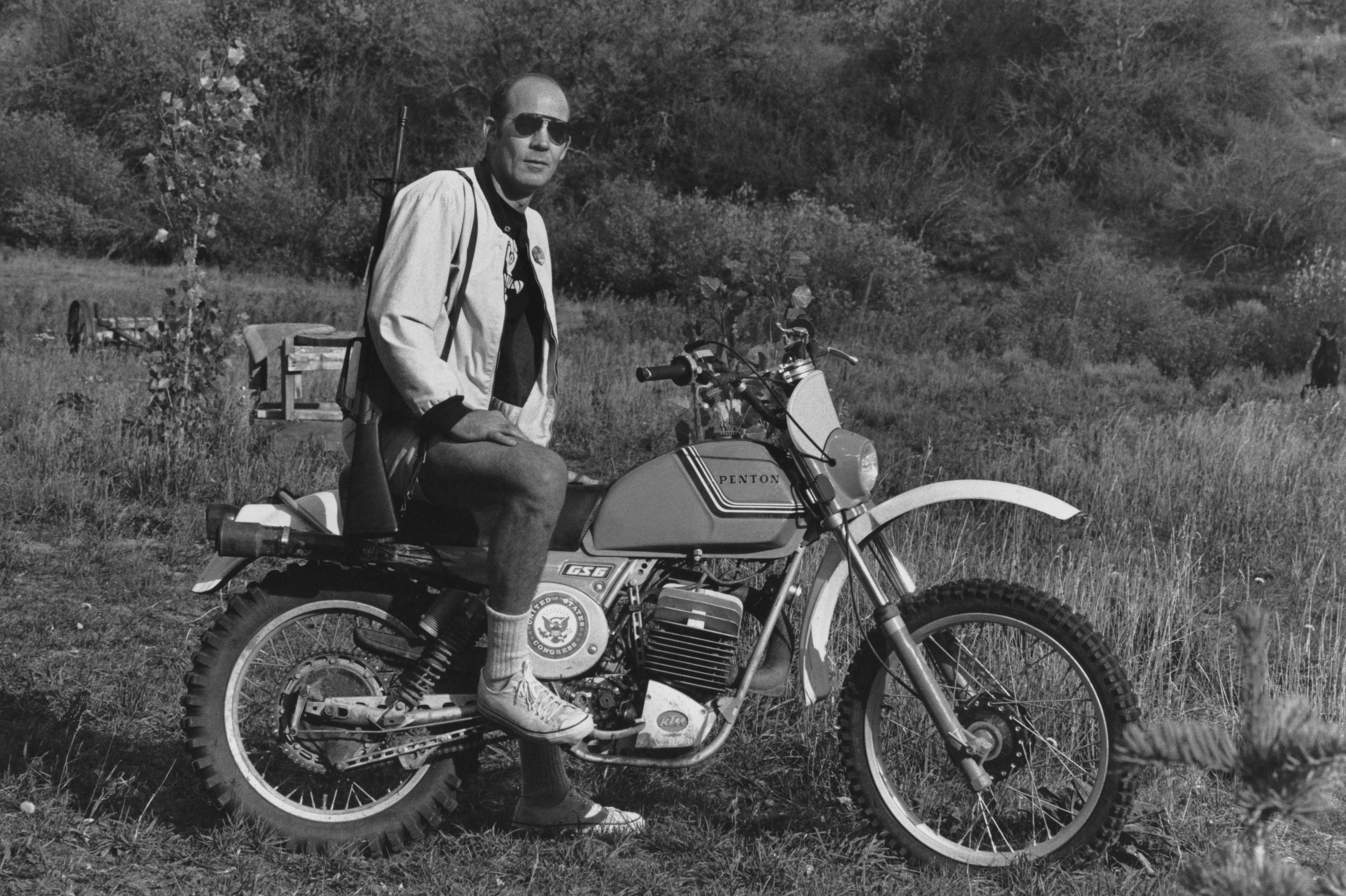

I have been warned that I would be under penalty of death if I revealed the directions in print, so let’s say the house is way up there on the mountain. The site is called Owl Farm, and the house is a sturdy garrison of logs and glass, facing a postcard panorama with 50 wild acres behind it.

I see both cars in the snowy driveway, but there are no tracks, which means no car has left today. He has to be in there. As I approach the door I see a room that has been tacked onto the front of the house. A huge peacock is sitting on a shelf, his great tail hanging down in gorgeous colors as he peers through the glass. This anteroom is known as the Peacock Hotel.

I rap on the entrance door hard, and two female peacocks, the ugly half of the species, scramble and give me dirty looks through mean, beady eyes. I’m waiting for someone to answer the door. You’d figure that anybody who would breed and mother peacocks, tropical birds, 8,000 feet up in the Rockies can’t be all bad.

No one is answering. I trudge through three feet of snow to the back entrance and rap some more. Still no answer. I’m not about to hang round up there and freeze, so I go back to the tavern to find out if there is any message.

I tell Mike I was just up at Thompson’s house but couldn’t’ rouse him. “Did he shoot at you?” Mike asks complacently.

“Shoot at me?” I ask. “Does he do that?”

“Yeah,” he says. “Sometimes.”

Zip…back to my hotel in Aspen. I’m delving into airline schedules when the phone rings. It’s Hunter, the other Hunter, not the ogre of last night. It’s like I just arrived. He tells me he’s been in the shower for an hour, probably a cop-out for not answering my pounding on the door. “Meet me at the Tavern in an hour. We’ll have dinner and go up to the house and get this thing started.”

With trepidation, I take a taxi back to the Tavern. He and Maria are already there. I see a couple of cowboys at the bar and some local people at the tables. It is made plain that tourists are not welcome here.

I know Hunter takes it for granted that I understand the rigors of reentry after a tough night. I never mention the crazy cover-story pictures or any of the ultimatums presented the night before. Neither does he. It never happened.

Now he’s solicitous and polite. People seem to forget that Thompson was southern, raised a God-fearing, well-mannered little Kentucky gentleman, and that’s what he is when he’s straight. Fortunately, he’s not straight all that much. I like hunter when he’s in second gear, just a couple of double Bloody Marys on an empty stomach.

Now he’s a combination of the southern gentleman, the fey, absent-minded professor, the brilliant observer of today’s mores. Top this off with a tincture of his inimitable weirdness, and he’s a lovable guy. His following is devoted.

After dinner we start back up the mountain, Maria driving, thank God. The front entrance to the house leads into the living room. It’s a place to hibernate, big comfortable couches and a huge open fireplace.

Lining the top of the room is an array of hats, maybe 30 of them—Borsalinos, fedoras. Panams, cowboy hats, and more hats—a hat collection, a common fetish for guys with sparse hair.

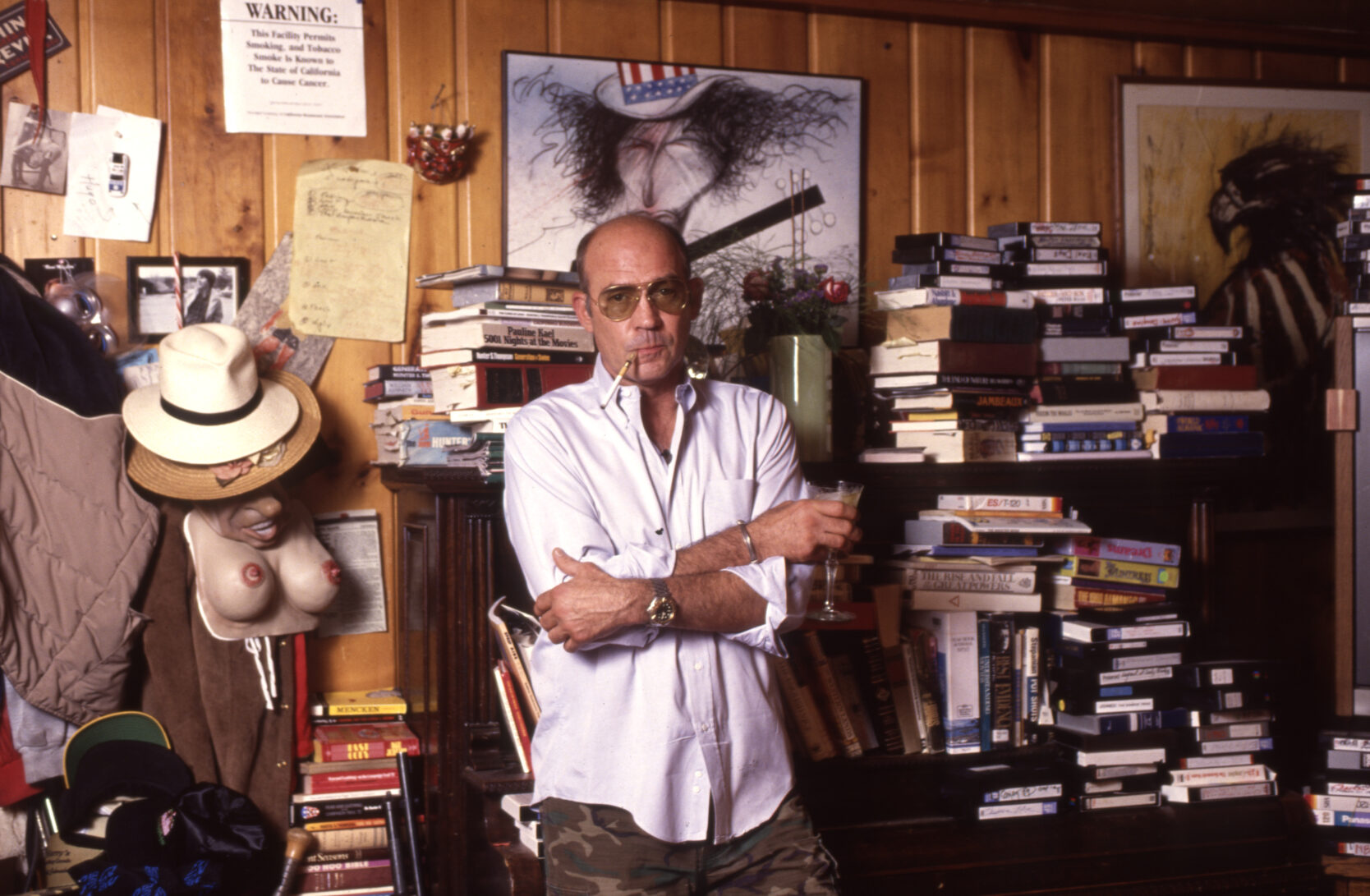

The kitchen is an all-purpose room with all the cooking equipment on one side. On the other side is a standup piano. Books are all over the place. The walls are festooned with photos, handbills, and the knickknacks a traveling man with a sense of humor accumulates.

Hunter points out his communication center, a big television set and stereo setup. He has a large satellite dish outside for reception. “How about this?” he says, patting a bulky piece of equipment, a telefax machine. “I just stick the copy for my column in here and it’s reproduced at the paper in San Francisco, over the phone line.”

“That saves a lot of time and bother, doesn’t it?” He gives the machine a punch. “I don’t know. I still haven’t figured out how to get the goddamned thing started.” We sit down at the kitchen counter, and I take out my tape recorder. He claps. “Yeah, let’s get started. What do you want to talk about?”

“You’ve upset the bus on many a political campaign. Who’s got the best shot at being the next president of the United States?”

Without batting an eye he says right back, “Richard Milhous Nixon. We’re talking winter book. I make him my winter-book favorite. Who’s a better bet right now? Bush? You kidding? Teddy’s gone. Jack Kemp? Bill Bradley? Cuomo? I see your twisted smile, but just think about this. Nixon’s clawing to get back. You can almost hear the scratch marks, and he’s not going to rest until he’s back where he thinks he should be. I miss the bastard. That’s the guy we need.”

“Need for what?” I ask.

“For Saturday Night Live. I was talking to Laila last night. That’s her department, arranging for Saturday Night‘s hosts. Nixon’s made to order. I gotta call her.”

For years Thompson despised Nixon and knocked his brains out, but a change seemed to come about, and it reflected in Hunter’s piece called “Presenting the Richard Nixon Doll (Overhauled 1968 Model).” He’s on the campaign trail with Nixon in New Hampshire in 1968, and he has somehow wangled a ride back to the airport in the car with the next president. Nixon is talking to him:

“You know, the worst thing about campaigning for me is that it ruins the whole football season. If I had another career, I’d be a sportswriter or a sportscaster.”

I smiled and lit a cigarette. The scene was so unreal, I felt like laughing out loud—to find myself zipping along a New England freeway and relaxing in the back seat, talking football with my old buddy, Dick Nixon, the man who came within 100,000 votes of causing me to flee the country in 1960.”

I think they became kindred spirits when Hunter discovers that Nixon was a knowledgeable football nut just like him. That took some of the curse off.

“How about your friend Gary Hart?” I ask.

“Hart? There weren’t enough votes in the unions to elect Fritz Mondale, and there will never be enough yuppies to elect Hart. The rare file and greedy, prone to panic like penguins, and naked of roots or serious political convictions. Jesse Jackson can crank more energy and loyalty and action out of 10 people on any street corner in East St. Louis than Gary Hart could ever hope to inspire in a week of huge rallies in New York, Chicago, and Pittsburgh.”

The phone rings, and he answers it briefly. “A friend of mine, a local, coming up for a few minutes…Hey, why don’t you do Jack Nicholson? He’d be a good piece for you.”

“I’d like to,” I say, “but I don’t know him, and he’s as elusive as you are.”

“I’ve talked to him about you. He knows who you are. I’ll get him for you.”

“Good,” I say, “But let’s get this one finished. Tell me about the drug culture.”

“There’s no more drug culture. It’s just big business, a foul business. I grew up in the drug culture in the ’60s. It was a pleasant pastime for good buddies and fellow travelers. Money had nothing to do with it. I never found that the things I did ever caused me any great grief. They did put a certain stigma on my rep, but if I did half of the stuff they say I did, I’d be dead.”

He pulls up his sweater. “Look at this.” He flashes a lean, washboard abdomen. He’s six-foot-three, weight 190, and is an impressive specimen at 47. Now he looks at me sideways and is quiet for a few beats. Then he says, “I know you, Harold. I know what you’ve been doing all these years, and you look as fucking healthy for your age as anybody. Now tell me. Should we have abandoned all that great fun we had?”

He says this kind of wistfully, and I’m getting his vibrations. I’m thinking of the exotic places where our paths have crossed, like the gambling joint in Kinshasa, Zaire, a hangover from the old Belgian Congo. It was like Rick’s Café, the faded joint Humphrey Bogart ran in Casablanca, only sleazier: CIA guys masquerading as Peace Corps workers; vamps of all colors; agents and spies from half a dozen countries; gambling, plotting, intrigue.

If you were a friend of the owner’s, he’d send one of his boys out to the fringe of the jungle, and he’d be back in an hour with a shopping bag full of buds—pungent, green dynamite—five bucks. One night Hunter threw a whole bagful of buds into the pool at the Hilton International, then dove into the water to be with his friends.

Hunter’s eyes seem far away. He takes a long draw of Chivas. When I ask him about his beef with Gary Trudeau and his “Doonesbury” comic strip, Hunter pouts. ‘I don’t want to talk about it.”

“Just fill me in. Wasn’t there a character in the strip named Duke, one of your pen names, and wasn’t it based on your alleged lifestyle?” He nods. And didn’t most of the people who read the strip assume the character was supposed to be your Thompson is nodding like a guest on What’s My Line. And isn’t Gary Trudeau a close friend of yours?”

He breaks his silence. “Never met him, never even seen him… he’s too small to see. He claims he made the character up himself… had nothing to do with me… it was his own invention.” Hunter starts scribbling on a piece of notepaper. “Gotta make sure this is accurate. Here.”

I can’t make out the writing. I ask him to read it into the tape recorder. He starts off in a stentorian tone: 1 have to live with these rumors. Look at that wretched little comic strip… that thieving, chicken-shit dwarf. I feel sorry for his parents. They worked and sacrificed to put him through Yale, and all he learned was to live like a leech and a suck. fish on other people’s work. It’s a shameful thing, and I know he’s embarrassed by it.”

“What about your new book?” I ask.

“Oh, it’s a monster. I was working on it for six months around San Francisco when this column project came up. You knew I was the night manager of the O’Farrell Theatre, the Carnegie Hall of public sex in America.”

“Yes, I heard. I’ve been wondering what the night manager does.”

“Well, I prowl the catwalks… see that the lighting is right… and, uh…” He seems stumped. And drool all over those sexy, naked young girls?” I add.

“No, no, nothing like that,” he answers quickly. “This was serious business. Jim Silberman, who runs Summit Books for Simon and Schuster, has been immensely patient. I took a half-million-dollar advance, and don’t ask me where the money is.”

“When is the book due?” I ask.

“Last year.” he says.

“Do you still do the college lecture tour?”

“I average about two a season. You know, when first started out on the circuit 10 years ago, I was talking to my peers, as it were, people who had shared common experiences. But with the kids today, it’s different. They act like I’m from some other planet. Their first questions are, ‘Is it really true? or ‘How do you get away with that stuff?’

“I feel sorry for some of those poor bastards I talk to… I can almost feel their frustrations. They’ve never had that kind of fun … they don’t know… It’s like me telling you about my previous life in China when I lived in Peking… in Shanghai… ah, that good old Boxer Rebellion.

“But the questions can get profound—like, ‘What’s your opinion of the validity of suicide?’ A favorite one seems to be, ‘Who are the three most important men of your time?’ ”

“Who are they?” I ask.

“Muhammad Ali, Fidel Castro, and Bob Dylan.”

“You want to give me a rundown on that rating?”

“Ali is one of the true heroes of our time. He spoke up in the ’60s and stood his ground. He also paid his dues without a whimper. Castro has been running his country for 26 years although everybody’s tried to get him knocked off, from the Kennedy brothers to the Mafia. And no matter what you hear in this country, his people love him down there. He’s a hell of a leader.

“Bobby Dylan is the purest, most intelligent voice of our time. Nobody else has a body of work over 20 years as clear and as intelligent. He always speaks for the time.”

Hunter puts his drink down and goes to answer the door. He admits his friend Tex from down below then goes to get his camera. I explain to Tex what the pictures are for, and he says he knows the game. He’ll take the pictures. He shoots Hunter at the typewriter, guzzling a drink, wearing the floor-length Indian headdress—Hunter is moving around like a Ford model.

Tex asks, “How many shots did you have in here?” ‘Twenty-four,” says Hunter. it was a fresh roll.”

“Seems like we’ve done more than that. I can’t tell. Better have a look.” He cautiously opens the camera. “Shit, man, you got no fuckin’ film in this camera,” Tex says eloquently.

Thompson galumphs over like a bewildered ostrich. “No film!! … Shit!” He looks over to me to cop a plea. I give him a sneaky smile and he knows exactly what I’m thinking—the old no-film-in-the-camera caper. “Playing games, Hunter?”

“I wouldn’t do that to you. I swear I thought there was fresh film in the camera. We’ll get more film and do it tomorrow night. I promise.”

I return to the mountain the next night to wind this thing up, but there is a two-hour delay. In the Thompson household, only first-strike and avalanche have priority over basketball and football games. Hunter demands action wherever he is, and this is action for him because he’s involved. He’s betting on most of the games. The Louisiana–Memphis State game has just started and I have to wait for the whistle to blow to get a word in.

Thompson is nursing his Chivas Regal. His face is animated and there is a kid’s gleam in his eye. His team is winning. It’s 12 years now since he jumped into the pool that night in Kinshasa. Considering that he’s galloped through those 12 years like a guy riding a wild bronco, he hasn’t changed all that much.

It’s still fun and games to Hunter. He seems to have friends no matter where he goes, and when he hits town, it’s New Year’s Eve every night while he’s there. His mountain is his sanctuary. That’s where the brain and the arteries are given a chance to be restored to their normal functions. Not that he lives up there like a monk, but it’s far from the lifestyle his cult likes to think it is.

But what the hell has he been doing up on the mount all this time? The Great Shark Hunt was published in 1979 and it was a big winner. A novel, The Curse of Lono, came out in ’82, a best-seller for a short while, but far from his best work. He did several magazine pieces for Rolling Stone, where he was a pillar for many years, but it was obvious that this medium isn’t much fun for him anymore. He has spent a year playing around with his new book, and has now become a newspaper columnist.

The Thompson cultists have been bemoaning the scarcity of their hero’s product. They want to know why he hasn’t been up there beating that typewriter and meeting those deadlines. If he were the kind of guy who could settle down and hack away at his typewriter merely because he was committed to his craft, he wouldn’t be Hunter Thompson.

Strange. The followers adopted him because they discovered this wild writer, their kind of guy, a rugged individualist with a weird sense of humor and a lifestyle that so titillated the uninitiated that the stories and gossip became an introduction to his work. Now they want to reform him. That’s never going to happen, but if it did it would be a shame because it would be the end of a rare species.

There’s only one.

Thompson paid his dues in his early years. writing (or obscure publications for little money and sometimes for free, but he became a pro in a hurry when the money started to roll in. If there has been a lack of motivation in Hunter’s drive to enrich and fatten his body of work. it might be that the solves at the door aren’t as hungry any more.

He’s had some good touches over the past decade. A bundle from Universal Pictures for episodes of his life, made into Where the Buffalo Roam. It has become a cult movie, it was that bad, but Bill Murray turned in a remarkable portrayal of Thompson. There’s been the income from some very profitable best-sellers, plus the hefty advance from the new, unfinished book.

The basketball game is almost over now. but Thompson doesn’t budge until the final whistle. Then he gets his camera, and this time I check it for film. He goes through all the same poses as the night before, with Maria doing the shooting. When were finished, he says he thinks this exhausting work has earned us a nightcap at the Tavern, so down the mountain we go. It’s about five below, and Hunter is wearing shorts.

There are several “final” nightcaps, but I have to catch a plane in the morning. Ten minutes after they call a cab for me, a wild-looking guy walks into the place. Thompson walks over to him and starts talking. I don’t know what he is saving, but whatever it is, I can see it’s something intense. Then he comes back to me. “That’s Weird John, your driver,” he says.

“What were you just telling him off about?” I ask.

“I was merely telling him to be careful… that you were a good friend of mine . . . and that if anything happened to you, I would kill him.”

On that warm, happy note. I took off from Woody Creek and headed back to the mundane.