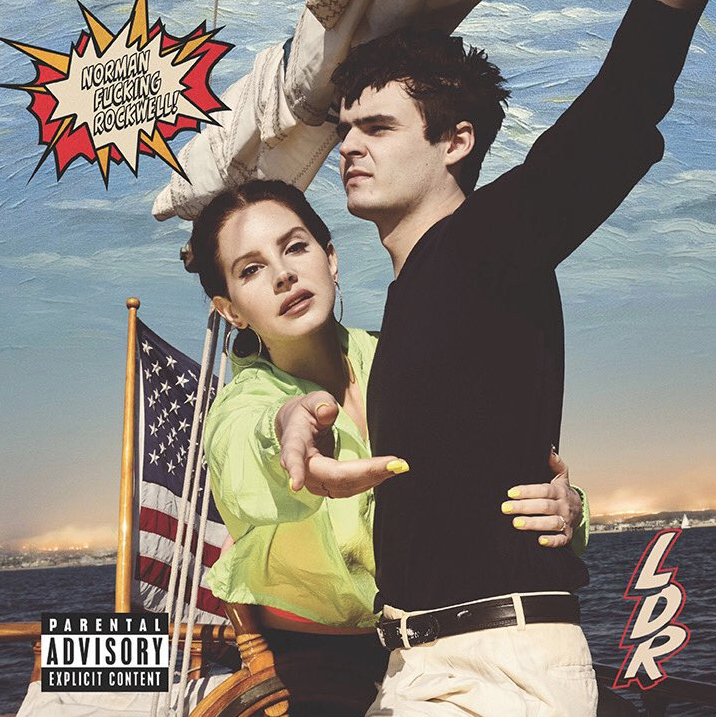

Lana Del Rey is no longer alone. At least, that’s what the cover of her new album, Normal Fucking Rockwell!, seems to convey. Instead of posing solo, as she does on all her previous releases, she stands here on a sailboat steadied by the trunk of Duke Nicholson, grandson of Jack. If there were some kind of messaging at play, a subliminal note that Del Rey had finally found stability after notebooks filled with tales of whirlwind romances, it’s dashed by the harsh light of the morning after. “God damn, man child,” she sings to open the album delivering the line with a swagger and an implied sigh. It seems, perhaps, that dates who deface the Hollywood sign don’t produce the most profound lovers. It would be wrong to call Norman Fucking Rockwell! a practical album; it still indulges in a romance that’s breathless and simple. But it’s an album wisened to the cracks in its cinematic California facade.

Despite the East Coast WASP-iness of its namesake, Norman Fucking Rockwell! Is still soaked in imagery of the Golden State. An alternative album cover, produced solely for a vinyl deal with Urban Outfitters, features Del Rey flanked by friends, including Father John Misty’s wife Emma Tillman, palms turned upwards and legs crossed—an homage to some idealized version of the blissed out Laurel Canyon scene. “We’re all in a little bit of an ‘om’ meditative pose,” Del Rey said in an interview, “kind of in the style of Ladies of the Canyon.” And the region’s influence is felt beyond the cover. The ghost of Carole King’s Tapestry and Linda Ronstadt’s “Heart Like a Wheel” haunt the opening piano of “Norman Fucking Rockwell”; elsewhere, Joni Mitchell’s syncopated vocals find a spiritual companion in the spoken-word bridge of “Mariner’s Apartment Complex.”

But, of course, Laurel Canyon was always more than a specific place, or even a particular sound. Norman Fucking Rockwell is instead far more of a metaphysical exploration of what the era represented. Del Rey isn’t afraid to give into the lore. “We were just that good, it was just that good,” she sings on “The Next Best American Record,” but the darkness that accompanied those decade-defining albums—the drug abuse, the political unrest, the fuckboys—is also a fitting frame for the melancholia that has always occupied Del Rey’s output. “I moved to California, but it’s just a state of mind,” she sings on “Fuck It I Love You,” all too aware that anxities can trail a cross-coast move. And whereas the David Geffen crowd had the Vietnam War, the stakes are now far more dire: “L.A. is in flames, it’s getting hot,” she sings on the closing coda of “The Greatest,” the closest the album ever gets to an outright political message.

Then again, there is an inherent politics to female depression, an unruliness in a beautiful woman who dares to cry for help. In a city that devours the emotional breakdowns of its brightest stars, Lana Del Rey has never shied away from sadness; but here, she brings the weight of her full despondency to its logical conclusion. On “Happiness is a Butterfly,” she muses about dating a serial killer: “What’s the worst that can happen to a girl who’s already hurt?” And on the majestically titled “hope is a dangerous thing for a woman like me to have—but i have it,” she creates a public display of depression, comparing herself to Sylvia Plath, then a sociopath, all while prancing around Los Angeles in a nightgown. When her pen simply won’t do, she writes in blood.

Being bombarded with mortality is a tall order for what is ostensibly a summer pop album; but rather than let her words fade into the background of washed synths and drum machines, as on previous releases, the breathing room in the production of Norman Fucking Rockwell leans into the intimacy. Empty space has become somewhat of a trademark of pop svengali Jack Antonoff, who signed on to produce the album after allegedly playing Del Rey a chord progression that would become “Love Song.” The minimal accompaniment, often just a single piano, lends a tactility to her voice; on the chorus of “Bartender,” her whispered repetition of a hard “t” sound nearly reads as ASMR. When things do spiral out, on the long outro to “Venice Bitch” and the warbled synth lines of “Cinnamon Girl,” it feels like the modern compliment to an extended Lookout Mountain jam session. But whereas artists like Kasey Musgraves use hazier textures to reflect a stoned sense of mind, Norman Fucking Rockwell isn’t afraid to veer dangerously close to a bad trip.