This article originally appeared in the December 1988 issue of SPIN.

In the last couple of years, science fiction has tossed off the little-green-men albatross and turned overnight into a sleek, well-oiled, dangerous thing—a matte-black Stealth bomber constructed of words. It has acquired all the sinuous grace and breathless, sweaty eroticism of the finest rock’n’roll; it kicks in with visceral urgency that smacks of addiction.

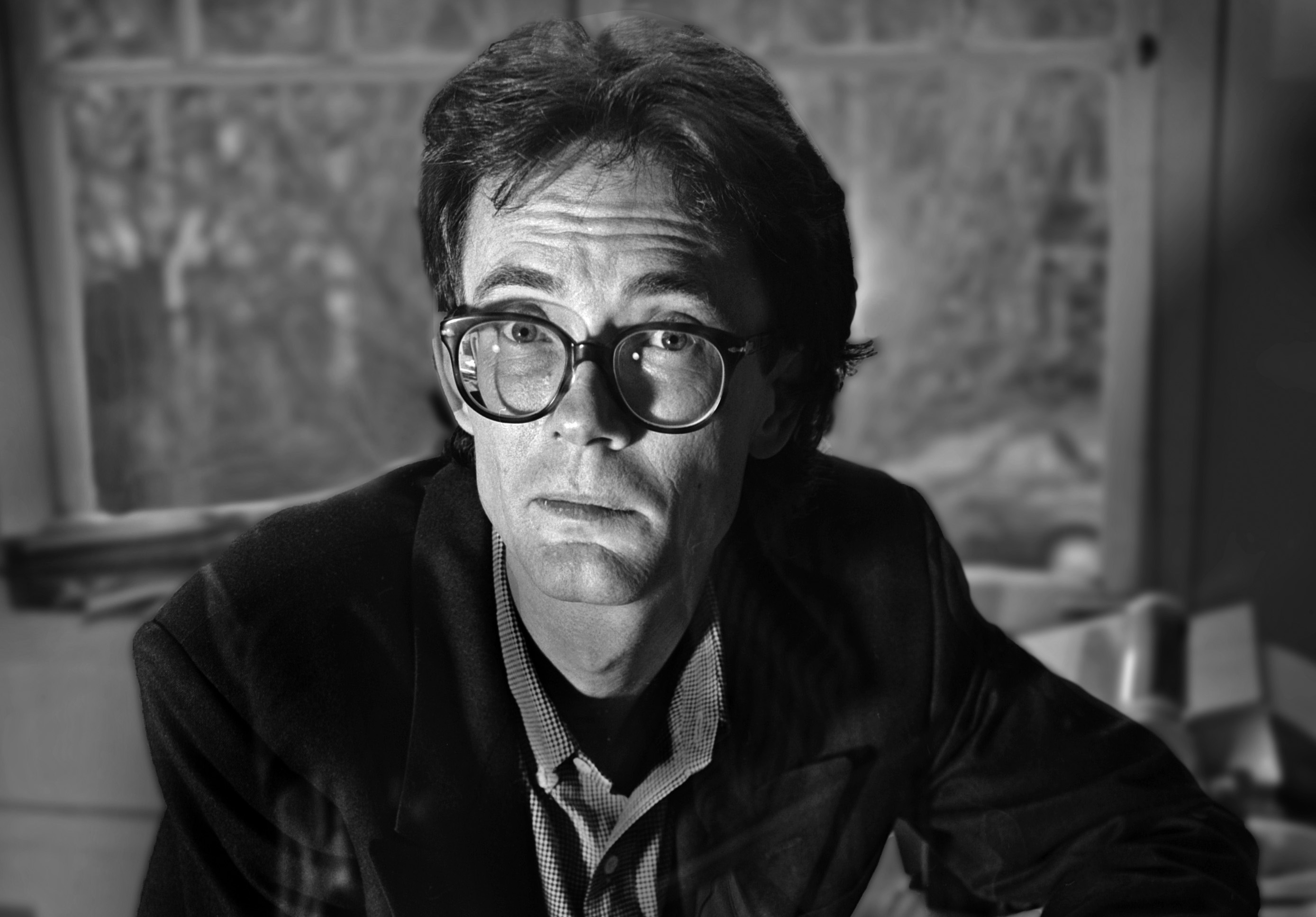

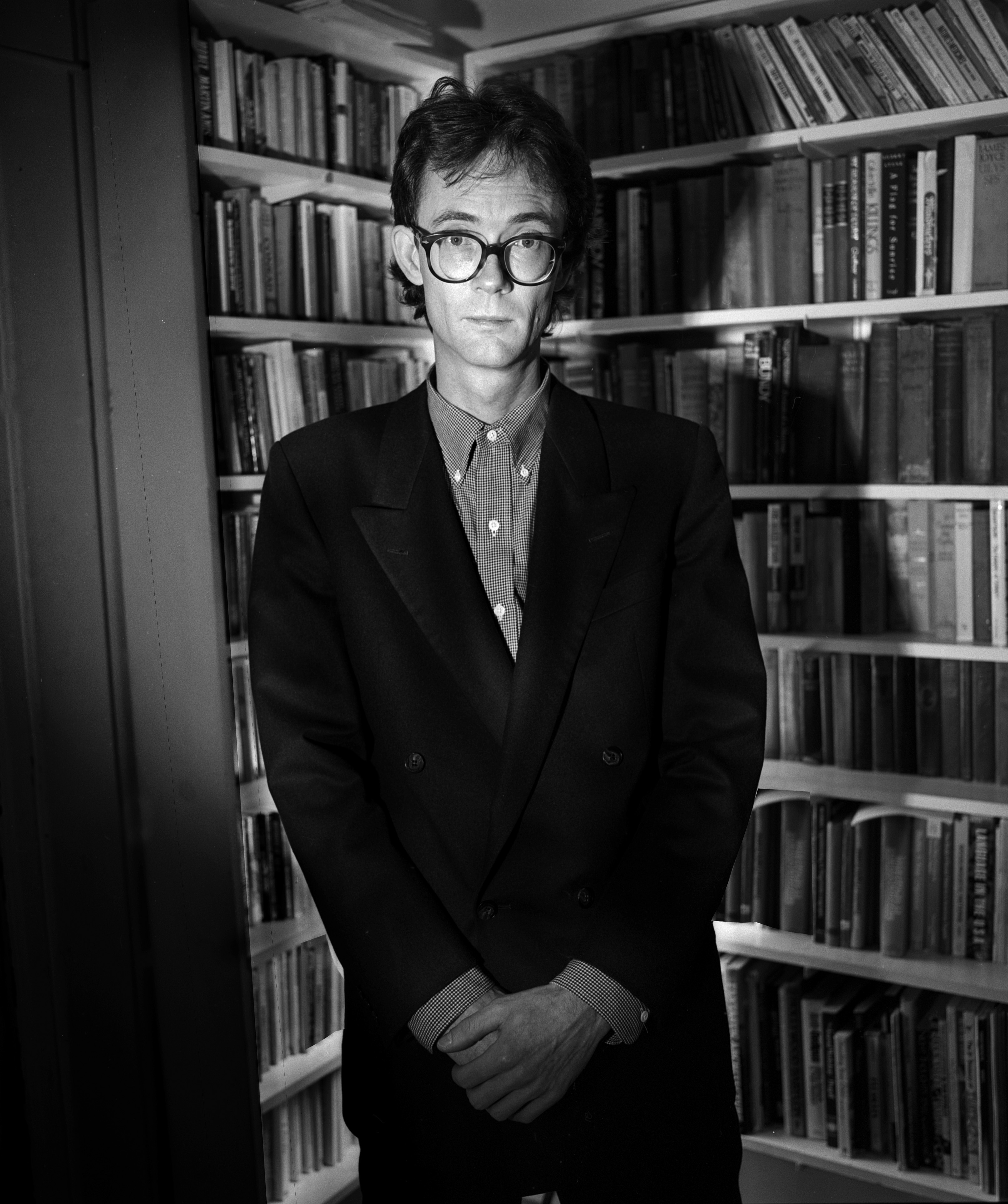

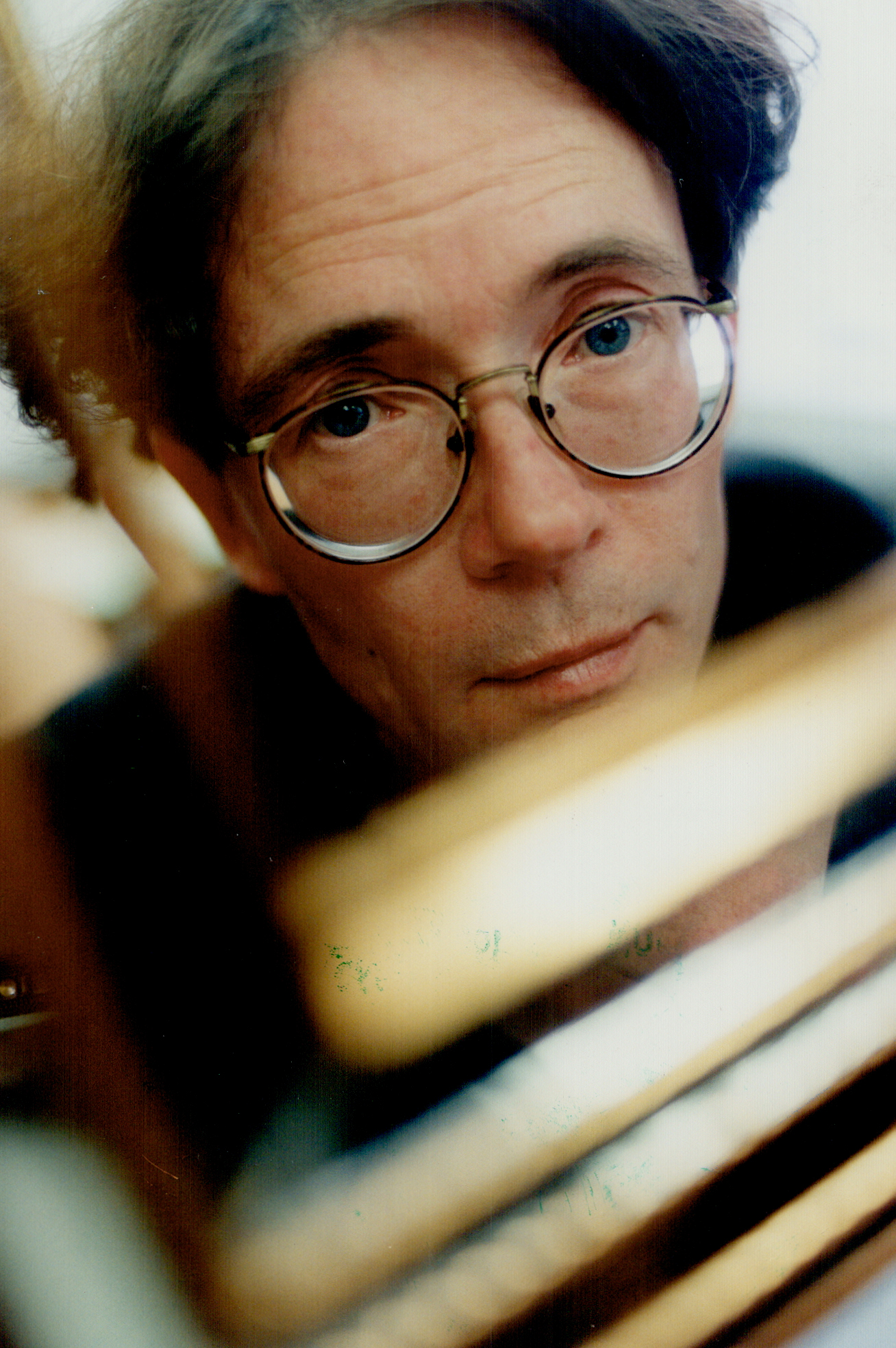

To a large degree, this is due to William Gibson, whose writings—Neuromancer, Count Zero, Burning Chrome, and the new Mona Lisa Overdrive—have taken the mainstream’s assumptions about science fiction (nerdy, reactionary, desexed) and rotated them 180 degrees on their vertical axis. Gibson’s stuff is the reactor-core steam of all tomorrow’s parties breathing down your neck today. He has smashed a hole through the moribund haze of the science fiction subculture like nothing since the New Wave of the late ’60s.

Gibson was the point man for what is now known as cyberpunk as soon as his writing hit the light of day . He is responsible for most of the innovations that have become, regrettably, the fixtures of the almost-cliched-by-now generic cyberpunk story. Cyberspace—the shadowy four-dimensional universe of data that his computer-jock protagonists jack into — and the Sprawl—an artifact of the terminal stage of urban overrun, a single city that covers the entire Eastern Sea board from Boston to Atlanta—are his inventions.

While the latter had long been a staple of bad science fiction, Gibson makes it breathe: When he writes about it, you can smell the heavy, fetid, urine-laden air and feel every drop of grime sputtering down from the sooty geodesic “sky.” Most of the mood of cyberpunk—the pacing, the language, the brand-name physicality—can be traced to his lead. His first short stories (the brilliantly incendiary troika “Johnny Mnemonic,” “New Rose Hotel,” and “Burning Chrome,” published in OMNI magazine at the dawn of the ’80s), wasted no time in establishing his trademark intensity as the standard by which all other future SF will be measured. It sent a shockwave through the science fiction community that brought similarly minded writers crawling out of the woodwork, and nothing has been the same since.

So here’s the scene in, say, 1982: You had a bunch of talented, aggressive writers kicking around the lower reaches of recognition, trading fusion-hot stories of attitude and high-tech flash through their rather incestuous ghetto until somebody came along and noticed that all these new talents shared a worldview and a set of assumptions—and called them cyberpunk. Their work was hard, fast, brutal, and uniquely influenced by the rhythms and idioms of rock’n’roll, and more specifically punk rock.

Gibson, then 34, clocked in with a battery of blitzkrieg stories about hardened, cynical mercenaries and three-time losers. His prose was crammed with detail, a hyper-burst transmission of stunning evocative power (“sky . . . the color of television tuned to an empty channel”) riding a crystalline carrier wave of almost painful beauty.

Along with others like Bruce Sterling, Greg Bear, and Rudy Rucker (all featured in the cyberpunk anthology Mirrorshades), Gibson was a new factor in the science fiction equation, usually oblivious to the world around it. SF had been dominated for years first by sludgy, phallocentric space opera and then by the “radical” New Wave, which quickly became at)out as daring as “The Cosby Show” after showing a certain initial promise.

The best cyberpunk—say, Gibson’s Neuromancer (recently named one of the 100 best science fiction novels of all time)—is a powerful way of perceiving the here-and-now world. It’s about the overload we’re already living with in the late 80’s. The sort-of trilogy of Neuromancer, Count Zero, and Mona Lisa Overdrive is much more revealing of our present mediascape mindset than most nonfiction. It concerns various people—drug-runners, indie computer saboteurs, even art consultants—who brush up against a presence in the cyberspace network that wasn’t programmed in, a true artificial intelligence.

The ways in which the thoroughly human characters come to terms with this terrifyingly new form of consciousness provide much of the cerebral kick; the gutbusting drive is what brings you off at a purely animal level. With its thoroughly contemporary themes (drug gang-war with everything up to and including tactical nukes, finding some kind of redemption at the edge), it’s not so much a fantasy construction of an imaginary future as a highly specific look at a present in mid-stage adrenalin OD.

For this reason, as soon as the first genre pieces were published, resonances began to be felt in art, in video, in music, in advertising. It’s an attention-grabbing style: You don’t forget it once you’ve seen, heard, or felt it. Even if you don’t know it, you’ve already seen the cyberpunk aesthetic in action; Blade Runner and “Max Headroom,” Apple Computer ads and rock videos. Whole bands have adopted elements of the look as their own, with varying degrees of success. Something like the cover of the Jesus and Mary Chain‘s Psychocandy is pure cyberpunk, as is the ludicrous excess of the late (wannabe cyberpunk) Sigue Sigue Sputnik. A handful of writers have made their presence felt bigtime.

The effect of the new writers’ arrival en masse was very much like that of the Sex Pistols ’77 cutting through layers of “progressive” art-rock and slovenly metal with amphetamine glee. Gibson is quick to acknowledge the influence: “1977 was delightful for me; things had been very boring and then all of a sudden there was something to watch. I went with these old hippie friends to see a punk band in Toronto. I walked in and I said, ‘This is fucking great,’ kind of like J.G. Ballard-meets-Jean Genet. Then a couple of days later a friend of mine brought the first Sex Pistols singles and a bunch of xeroxed fanzines back from England, and that started me buying records. It was a definite boost—it fit right in with what I thought science fiction was supposed to be about.”

And in Gibson’s stories, that’s what it’s all about. Even at the surface level, you can see influences turn up in his writing that traditional SF wouldn’t touch in a hundred years: the bites of Velvet Underground (a space tug called “Sweet Jane”; a character who recites “first thing you learn is you’ve always got to wait” like a mantra), the orbital Rasta colony Zion that juices a constant soundtrack of sensuous dub reggae, the constant acceleration and abrupt cornering that recall the rhythms of hardcore punk. This man, who started writing out of “quiet desperation” and “not having anything better to do,” has tapped straight into our collective cultural mainline in his first couple of full-length works, and shows no sign of stopping. I talked with him about his influences outside of science fiction and the ways in which life has been taking crib notes from his art.

* * *

Your books so far haven’t really been geared to the science fiction audience. There are references, almost in-jokes, in your work that somebody used to Asimov or even Harlan Ellison wouldn’t catch.

I was always pretty amazed when I saw people I considered reasonably hip to be reading my books. That was very gratifying—’cause I thought basically I’d be getting mainstream science fiction readers, and most of what I wrote would go right by them. So it was nice to see people reading it who would catch some of the references.

You draw strongly on rock ‘n’ roll pace and attitude. Have you seen any bleed-over going the other way—your work influencing current music?

The only place I’ve seen that is in Japan. When I was in Tokyo in February, there was some kind of industrial rock band called Wintermute (the name of the artificial intelligence in Neuromancer), and these kids kept appearing, ducking out of the shadows and handing me their demo tapes, getting me to autograph their jackets. It was weird how into it they were.

Maybe people get that deep into your stuff because it’s so immediate. It seems to me to talk just as much about day-to-day life now as about some constructed world of twenty years from now.

The convention in science fiction is that you’re supposedly talking about the future. But I’ve never felt that I was quite doing that—I’m writing about the present. When you get right down to it, most science fiction really is—the Heinlein and that stuff from the ’50s is clearly about the ’50s, the New Wave was about the ’60s. I just felt there was a lag in the ’70s, a lag that happened in a lot of different kinds of pop culture, and it’s just now that you’re starting to see ’80s music, ’80s science fiction.

Japanese culture is a strong presence in your work—the yakuza, the Japanese hypercorporations. Given that America is probably in decline, do you see Japan, or the whole Pacific Rim, as being the dominant global cultural influence in the next couple of decades, or is that just your conception of the present?

That is kind of the way I see the present. Living where I do, in Vancouver, it’s hard to escape the whole Japanese or Pacific Rim flavor of things—there’s a strong and obvious Japanese business presence here that is impossible to ignore. Actually, one of the hipper scenarios I’ve seen lately is Bruce Sterling’s, where he has Japan in decline—kind of where America is now—and the really hot places are Singapore or Taiwan. And it’s funny, when I was over in Japan, they would tell me, “I really like this future Tokyo you’ve got in your stories, but you really must have been thinking about Hong Kong.” Tokyo is really very clean—eerily clean, like Zurich, sort of. I think of it as the Confucian ethic going on. They don’t throw cigarette butts on the street, they have little ashtrays on every lamppost. And they’re emptied quite often.

Can you imagine that in New York? I mean, even it they had ashtrays on lampposts here, they’d over-flow in ten minutes and never be emptied…

New York is a weird place. If I had been living there all this time instead of living in Vancouver, which is an extremely soft environment, I’d probably be writing about unicorns and elves. I don’t think I would have been able to quite focus on the intensity, although there’s a writer named Jack Womack who lives in New York—his stuff isn’t being sold as science fiction, but it’s mostly set in an unbelievably bad New York of the near future.

If you dropped the characters from Neuromancer into his Manhattan, they’d fall down screaming and have nervous breakdowns. If you hate New York, this guy’s for you. Womack is from Louisville—I don’t think native New Yorkers or even case-hardened people who have been there a long time can perceive just how heavy it is. They can’t—it’s an anti-survival trait to be too conscious to what’s going on around you. I’m always worried about what I’m going to see in New York. Every time I’m there I see at least one thing I don’t want to have to remember.

I’ve often thought it would be a good idea if we could make a deal with the Japanese, kind of subcontract out or let them run New York for a decade or so, as long as they’d give it back. They’d get everything cleaned up and going.

That sounds really sinister—it smacks of getting the trains running on time.

Well, it’s a totally different mindset. I don’t know, maybe that’s why my books seem to be so popular in Japan; my suspicion is that they get a kind of perverse kick out of seeing this absurdly entropic view of their own culture. For the same reason, a lot of their better comics are set in a broken-down, post-nuclear holocaust Tokyo.

Have you been paying any attention to what’s going on in comics right now?

Not really. I try, but there’s so much interesting stuff going these days that it really has to be forced on me—”Hey, you’ve got to check out Frank Miller.” I liked Howard Chaykin’s American Flagg; Bruce Sterling turned me on to that. We tried to have it nominated for a Hugo one year (the science fiction equivalent of an Oscar) but they wouldn’t accept it.

No, the last time I was a fan was with the underground comics in the ’60s, that was the only time I went out and bought everything. Now there’s so much of it, and so much that’s apparently pretty good, that it’s hard to keep track. Although Neuromancer is going to be a comic, a graphic novel. I’ve seen it, it’s kind of neat, although the characters look a little healthier than I had imagined.

I know you’re working on the screenplay now for Aliens III, with James Cameron. Are there still plans to film “New Rose Hotel”?

Yeah, I sure hope so—I’m on page 83 of the screenplay right now. What we decided to do is shoot it in Tokyo, and not treat it as a science fiction story. Just say, this is about now, and treat it as a story about industrial espionage in present-day Tokyo. I’m very happy with that idea. I thought Tokyo is a lot more interesting than having to build a Blade Runner set, although it’s probably going to be hell to try to shoot there. The director’s going to be Kathryn Bigelow. She did a film last year called Near Dark—it was great, there was a scene in a redneck bar, the best thing I’ve seen in years.

I remember that film, it was a good example of the cyberpunk ethic popping up unexpectedly. I went to see it just expecting a generic horror film and was totally blown away. It was so intense. I love when stuff like that just unexpectedly boils to the surface of pop culture—like seeing Survival Research Laboratories on MTV.

Yeah, speaking of them, they pop up in my new book [Mona Lisa Overdrive], in a way. One of the main characters is a Mark Pauline type, kind of an ex-car-thief guy who builds giant robotic monsters. I don’t know him personally, but I’ve always loved his stuff. My favorite tape of theirs is a performance they did at Area, this club in New York. In the background you can see these cool New York art people just standing there with expressions on their face like, “Should I run? Am I going to die now?” Talk about intensity, they’ve got it.

* * *

And so does William Gibson. If you are bored and jaded with so much of what passes for literature these days, get with the program. Pick up one of his books (it’s probably best to start with the short-story collection Burning Chrome, just to immerse yourself in his weltanschauung). And you’ll know why he’s the hottest writer going, and why his cyberpunk vision is the way to fly the unfriendly skies of the late ’80.