This article originally appeared in the September 1985 issue of SPIN.

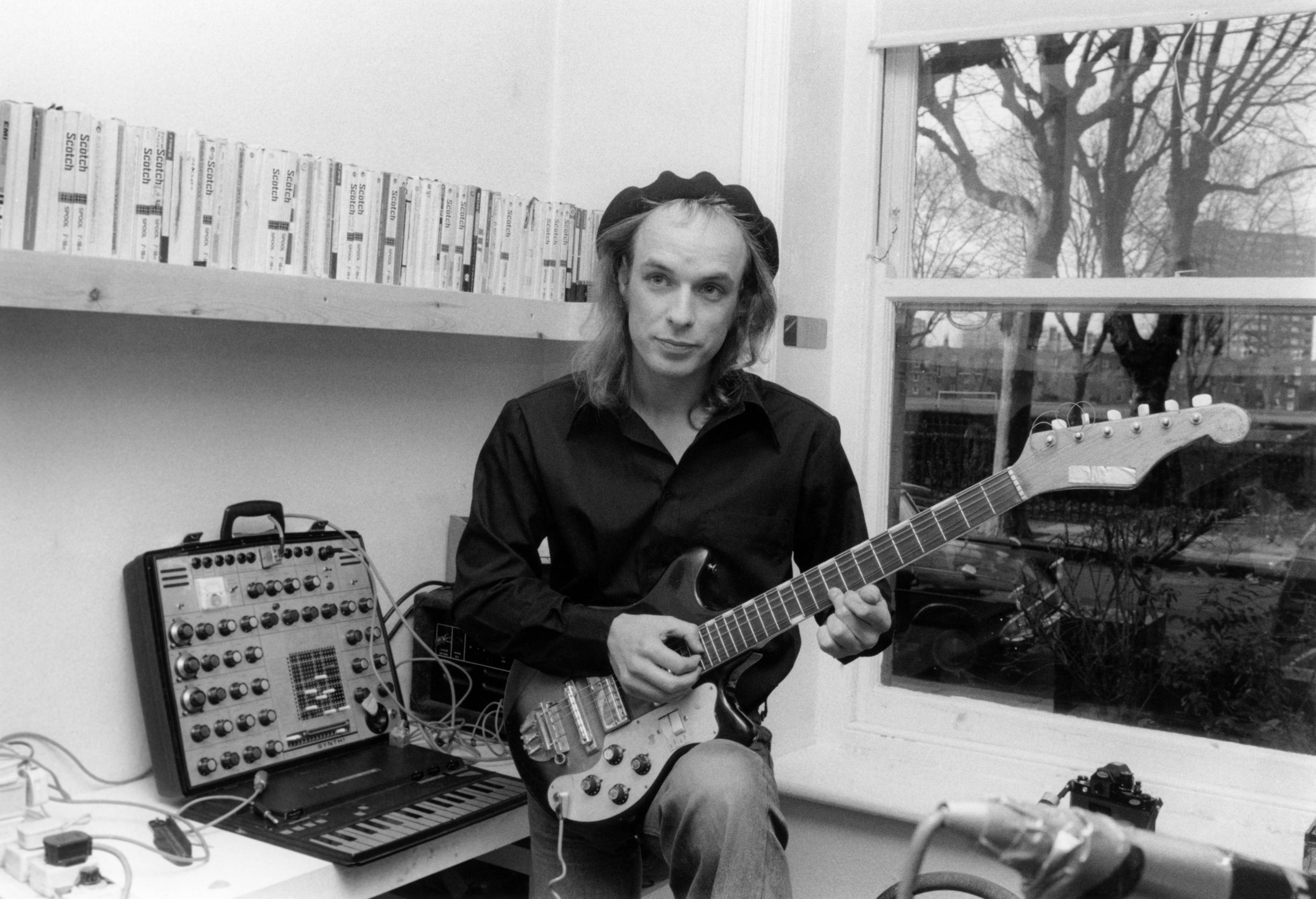

What sort of keyboards interest you these days?

Well, funnily enough, the technologies that interest me aren’t as much electronic as mechanical. Whilst recognizing the really extraordinary achievements that Fairlights and Synclaviers and so on represent, I’m actually not that interested in working with them.

I like simple instruments—I always have. I’ve always used very simple synthesizers, and I prefer them because I don’t particularly care to be faced with limitless possibilities. I enjoy an electric guitar because it has maybe six good sounds and then a few variations on them. I prefer a slightly more constrained situation.

I’m sure if someone gave me a Fairlight and I was shut in a room with it for a week I would get excited about it, but I’m not unexcited about the things I already work with. So I haven’t really worked with it that much.

One of the most interesting ways to approach any technology is to not read the handbook and to maintain that mental attitude of not reading the handbook. I use that as a kind of metaphor for an approach. Of course you read the handbook, but then it’s important to realize that any kind of machine is always designed for a historical function. It’s designed to do something that people already understand, and do it better than it was possible to do before.

But nearly always the real strength of a technology is that it opens a possibility that didn’t exist before, and that possibility is usually not just a modification of an existing process, it is a new process.

Consequently, until quite recently the whole accent of technical development in recording was to make more and more hi-fi recordings. The function of the studio was to give you fidelity, to make a faithful reproduction of a performance.

The studio is a place where and from which music is made, and as soon as you have that notion, forget about high fidelity, forget about anything—think about sound. It’s a place for developing texture, and texture is the primary innovation pop music has given to music.

I had an argument with a classical musicologist, and she said there’s nothing new in pop music. Every compositional idea was quite familiar by the time of, say, Stravinsky, and every melodic idea goes back to 1720, or something like that.

She was right, except that popular and electronic music have introduced a whole new currency into the musical vocabulary: sound texture. That is something you really couldn’t play with very much before the recording studio. It was like having a pain box with a limited range of colors: the piano, the clarinet, the violin, the contralto, whatever. Now you can design your own colors, which is an amazing breakthrough; it makes it a new art form.

Is Mozart a good example of that? Because he purportedly did have the ability to hear those things.

So they say. But I think that’s why—I’m going to say a terrible thing now, which should be very unpopular—I think that’s why his music is so absolutely tedious. He probably did think he could hear the whole thing in his head. Apart from in the slower pieces he wrote, he’s a show-off, and I’ve never been impressed by him for that reason.

There are three areas in which you have child prodigies: chess, mathematics, and classical music. Those are the only areas I know of in which children of 4 or 6 can do things usually done by much older people, things that show a real maturity of understanding, or a maturity of technical understanding.

I think it happens in those three areas because they’re all very simply describable. A chess match is a series of discrete moves and discrete situations. The don’t fade into one another; you don’t have a situation where the bishop is kind on the line between two squares. It’s either in one square or it’s in the next. Similarly, mathematics at that level has to do with discrete intervals. And classical music does, too.

It’s interesting to me that you don’t have child-prodigy painters or sculptors. They’re not found in any of the arts that have continuous surfaces in them, continuous graduations. I think the nature of classical music—this is, of course, a very sweeping generalization—is such that you could think you hear everything in your head, because it’s a series of distinct conditions performed by a series of distinct instruments. The clarinet in classical music is like the bishop in chess, if you like.

Modern music isn’t like that at all, because an electric guitar isn’t one instrument: it’s a thousand different instruments. The electric guitar Jimi Hendrix played isn’t the same as the thing Robert Fripp plays or the thing Ozzie Osbourne plays. We now have a situation that is much more fluid and contains subtle gradations between a few nodal points.

What do you think about digital recordings, compact discs, the laser-disc players, and so on? Where do you see any of that going?

I think digital sampling is in some way unnatural. It is not analogous to how the brain works. At least, I don’t think it is. Maybe the brain does work that way, but we don’t know about that yet. I think the nervous system reaches thresholds and then crosses them, and there’s an impulse generated.

It interested me that my response to digital as a listener is, “Yes, it sounds really nice.” Compact discs really do sound impressive, and the F-1 digital recording system, the Sony thing, is fantastic.

It’s a great asset, particularly the way I work—constantly dumping things on tape and then pulling them back into other pieces, and so on. With analog I always struggled against noise build-up doing that, which doesn’t happen with digital.

But I wonder whether there are elements beyond the obvious range of hearing that make a difference in one’s perception of music. For instance, I can’t hear above about 17 or 18 kilohertz, but if chances are made to the sound in the range that I can’t hear, say 20 kilohertz, I believe that I notice a difference in the sound. Now is this an illusion or not? Digital, of course, assumes that you don’t notice the difference in the high sampling rate it has.

What are you up to these days?

At the moment I have various video shows coming up. My video shows are rather peculiar things in that they’re instillations. I’m usually given a room in a museum or a gallery; recently, in Italy, I was given a church to work with. I take over the place and build video pieces within the structure; I make pieces of music that relate to that place.

The music I’m doing generally is eight tracks, not two—not normal stereo, it’s…whatever eight is…octoreo? These shows are mounted and stay up usually for a month or two. I have several of those shows coming up. A lot of my musical work relates to those kinds of installations and isn’t directed at records so much at the moment.

It’s an interesting idea because of how the music works: it’s carried on four independent tapes, so four stereo tapes play at once on four different machines. It’s designed so the tapes won’t stay in sync with one another, so the music never repeats exactly, because the tapes are all in different positions relative to one another. The videos are the same way. Every aspect of the show is reshuffling itself with every other aspect. That’s what I’m up to, mostly.

Where are the video shows you’re working on going to be presented?

I’ve got one out in Venice, then one in Dublin; I have one in Frankfurt at the Public Design Fair; I’ve got one in Ferrara, Italy; one in Angolême, France; and one in Paris. So there are quite a few coming up.

Apart from that, I’ve just finished working on a record [Hybrid] with a friend of mine named Michael Brooke, a Canadian musician who worked with John Hassell and a Canadian band called Martha and the Muffins [now known as M + M].

Daniel Lanois first produced them.

Daniel is also on Michael’s record and will be on my brother Roger’s record [Voices], which I’ve just finished putting a few touches to. There’s 11 years difference in our ages. Roger’s the younger.

Is that why he only recently appeared on your tapes and records? Has he just come into music?

No, there’s no special reason for that. He has been a musician for a long, long time. He began playing things when he was 8 or 9, and he was in the same brass band my uncle, grandfather, and great-grandfather were all members of. He’s a proper musician, you see; he plays things properly, not like me. He studied euphonium and piano, did a degree in music at a college in England, and began composing his own material and playing publicly.

There was just a point where his abilities seemed useful to me, so I asked him to work with me. I would say, Can you play this for me? I would sing something to him, get a sound on the synthesizer, and he would play that for me. But recently his own compositions have started to surface, and those look really interesting, too.

Is all the sound you’re working on related to the installations and video projects you’re doing?

Yes, pretty much. I’ve just finished a soundtrack for a film called Marie, which I believe comes out in September. It stars Sissy Spacek.

Are there any new groups in pop or avant-pop that appeal to you?

I have to think quite hard about that. There’s one group I was quoted as saying is the best in the world, which is a bit premature because I’ve never heard them. Somebody described to me what they do, and it sounds really interesting, so I think I’m going to like them. The group’s called Man Jumping.

What does Man Jumping supposedly sound like?

The description was of a large group. There’s a core of 5 people, but they sometimes perform, I’ve heard, with 20 to 50 people, and it’s rather like rounds. Do you know what rounds are? I don’t know if you have them in America. One person sings a line and then the next person pics up and sings a line, so there are several different lines going at once.

That sounds like your video shows.

Yes, it does. The impression I have about this group is that there’s an interesting systems approach to the music. But I must say lately I haven’t been listening to very much.

Have you heard the new Prince album yet?

No, I haven’t. I must say, though, that I quite like Prince, despite the heckling of most of my friends.