This is Part Seven of SPIN’s November 1985 cover story, “The Meaning of Bruce,” wherein we asked seven writers to consider the Springsteen phenomenon. (Check out the other essays by Tama Janowitz, Richard Meltzer, Amiri Baraka, Glenn O’Brien, Rich Stim, and Scott Cohen, respectively.)

How often, and how painfully, does Joe Strummer dream of Bruce Springsteen? Rock stars need press. The press needs rock stars. The relationship is ancient: The press is a barometer of a rock star’s celebrity, and celebrity regulates his relationship with the public. Some—Bowie and Jagger, for instance—have actually turned this relationship into an aesthetic: their stardom becomes part of the content of their work. The punks tried to turn their backs on the process, and the few who achieved stardom became ironically immobilized by it.

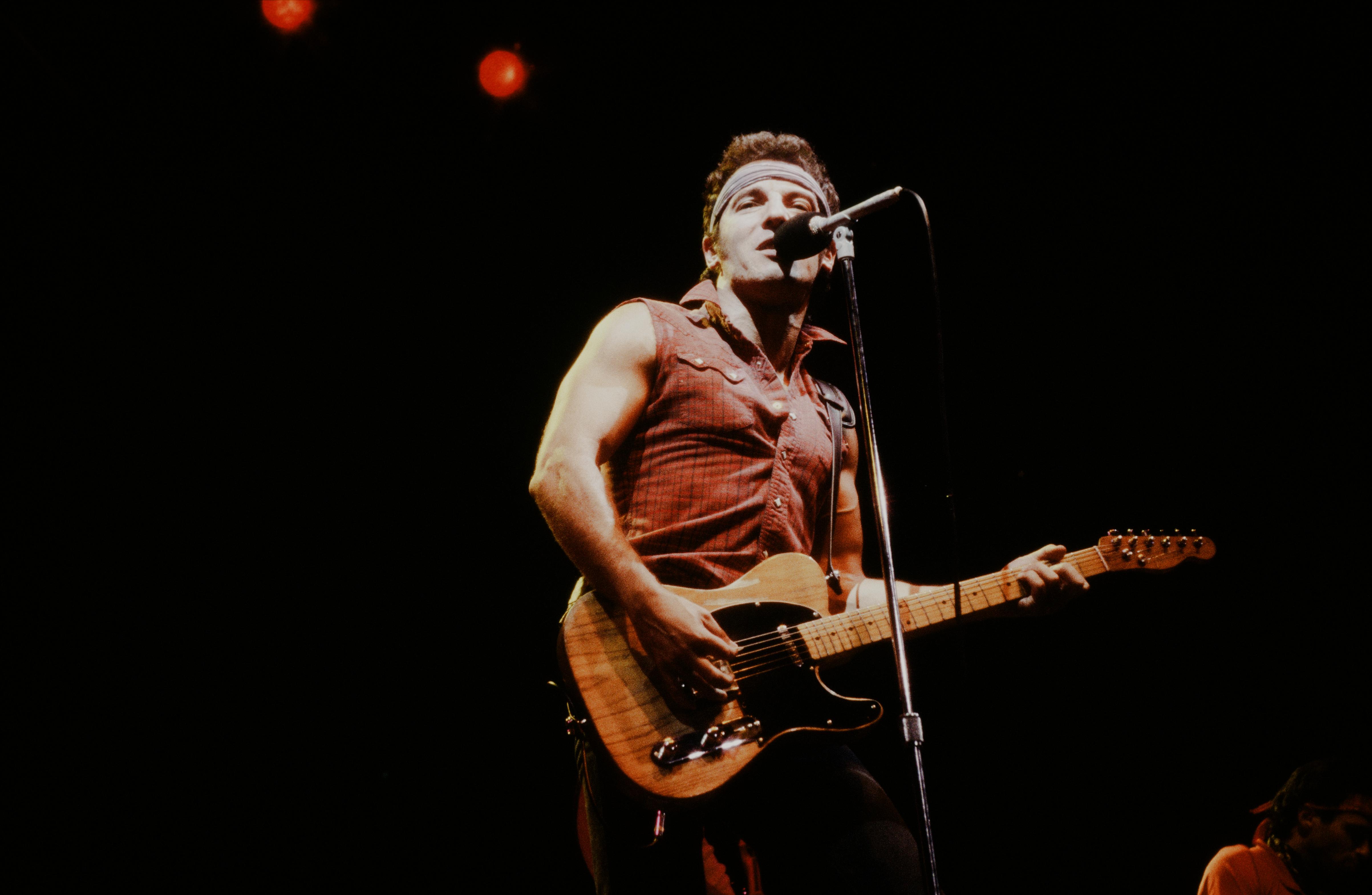

Ever since his unprecedented and grotesque coronation as “the future of rock ‘n’ roll” 10 years ago, Springsteen has developed his audience despite, not because of, the media. His legend has only one source—the live show. Longer, more powerful, more cathartic than any other, it is the perfect medium for Springsteen’s message. His work is about work itself—reflected in his almost mystical depictions of the working man, his belief in the American work ethic, and the blood-and-guts vigor he and the band put into any and every performance.

His concerts don’t bear comparison with other rock ‘n’ roll shows. The correct analogy would have to be more concrete: a tractor, a train, a pair of jeans—something durable, infallible, American made. The shows partake of the same mythology they illuminate, and it’s that which elevates them, gives them transcendent power. Springsteen may not have the greatest voice in rock ‘n’ roll, but listening to him live you hear the best rock singer in America. And though it’s essentially no more than a super-professional barroom combo, the E Street Band can sound like the best rock group in the world.

Also Read

SAME AS THE OLD BOSS

Watching Springsteen can be like watching Robert De Niro act—it’s the spectacle of star performer divorcing himself from his stardom. Whereas De Niro does it to make us believe in the character he’s playing, Springsteen does it to make us believe in him, which, because he’s a populist, is also his way of showing that he believes in us. In fact, he doesn’t fulfill the function of a movie actor so much as he fulfills the function of movies. Asked once why his shows were so long, he replied that it was so his audience could see their whole lives pass before them. And that perhaps explains everything: he would be Everyman.

When he tells stories about himself, they’re about everybody. You imagine that he’s the first rock star who dreams of being his audience as much as his audience dreams of being him. It’s a fair assumption that anyone who ever stood in front of a mirror with a guitar sees Springsteen as a projection of his own fantasies, but it’s not something Springsteen invites. With his wobbly dancing, aggressively unglamorous wardrobe, and hesitant, vaguely hokey anecdotes, he so appealingly looks like he could use being taught a few moves by his fans.

If this appears insincere, it probably isn’t, but is in fact a natural outgrowth of his songwriting. In 13 years, only his songs’ scale has altered significantly; his themes have remained constant. The progression from Greetings From Ashbury Park to Born in the U.S.A. is, as the titles suggest, a progression from writing about the people he grew up with to an in some ways more abstract and in other ways more specific definition of them as American symbols. Now colored by a certain nostalgia, Springsteen’s characters are still the embattled emblems of an old American dream, where the freedom to succeed usually turns out to offer the greater freedom to fail.

Which theme, demographically speaking, unites Springsteen’s audience and explains its range. He can speak for the dreams of youth and the soured reality of middle age equally and simultaneously. That a fabulously wealthy rock star, now allegedly making a million dollars a week and playing to 60,000 people a night, can pull this off is pretty extraordinary. Somehow, Springsteen makes us believe that his own conception of his work is sufficiently simple that there’s no credibility gap between himself and his work, between his privilege status and his dreams—in effect, that there’s no difference between him and his audience. Just as that giant, ageless voice seems to have rolled in from the dustbowls of Depression-era America, so his stage show appears idealistically bent on reviving the old, folky troubadour tradition of Woody Guthrie and Jimmy Rogers. That is, as closely as arena-scale logistics allow.

What this achieves is a neat reversal of an old ’60s cliche. If the ’60s were supposed to be about the formation of a community that idealized rock music, Springsteen is the creator of a rock music that idealizes the idea of community. It’s hardly surprising that he’s been chased around the country by politicians looking for endorsements. His community must now be vast, a potentially powerful lobby—something much wider than the dissident, counter-culture rock community of the ’60s and much more entrenched within the working classes. Which makes it ironic that Springsteen is popularly included in the media’s roll call of Americans restoring America’s belief in America. As others have noted, there’s a weird incongruity to “Born in the U.S.A.” being accepted as some kind of surrogate national anthem (read the lyrics). The record, and Springsteen, are light-years away from the right-wing orthodoxy that has largely fostered this new brand of super-patriotism. He is perhaps the only major public figure presenting the flip side of the coin who’s putting forward a cogent and realistic vision of America. He literally captures the times better than anyone else around.

But where does this lead him? Religion? Politics? He’s already beyond rock ‘n’ roll in the sense that there’s no one else within a measurable distance of him. So far his political activism has been confined to speeches from the stage and donations to workers and community groups in whichever town he’s playing. What’s next? On his last tour, there were already signs of conflict between the stridency of his speeches and the lush romanticism of his songwriting, especially his early songwriting. If there’s been a softness, a complacency, to his work in the past, it’s here. As a romantic, he loves the characters in his songs so much that he never brings himself to criticize them. And as Everyman, he lets them, himself, and us off the hook too easily. We leave his concerts being critical of life, but not of ourselves. It seems to be something he’s aware of: several of the Born in the U.S.A. songs and a new song, “Seeds,” that he unveiled on tour are harder, more dogmatic, farther along the road than he’s gone before.

And what does that mean? President Springsteen? Maybe not, but it opens up a range of possibilities. Among them the potential for being heard by a massive audience without having to work through the tyrannical stars-and-hype apparatus of the media, of celebrity. Because the truly extraordinary thing about Bruce Springsteen, whether one gets his point or not, whether one is fascinated or bored silly by him, is that he’s the only public figure in America whom one never suspects of being a cynic, a crook, a con artist, or an aggregation of all three.