Not until the last two years of his life did John Coltrane really stop performing jazz standards. He began to focus on ecstatic group improvisations (Ascension), harmony-free meanderings (see Interstellar Space), and more, experiments which set a template for so much of the free jazz and spiritual jazz that would be made in the wake of his death. But throughout his career up until this final act, Coltrane conscientiously adjusted his mode of playing and choice of material to his given context, remaining a consummate entertainer. At different junctures, he might have been responding directly to the cajoling of his record company, to the skill set of the players he was working with (Duke Ellington and Eric Dolphy both in 1961), or even the preferences of the crowd at a specific venue. He’d continue to perform relatively faithful renditions of jazz favorites several years after he’d pushed past the limits of traditional harmony, meter, and conventional saxophone technique at his most notorious live shows. The saxophonist highlighted this contrast in 1961 when he released a then-reviled, now-revered live album compiled from his Village Vanguard residency with the belligerently avant-garde multi-instrumentalist Dolphy and recorded selections for the languorously beautiful EP Ballads, featuring warm, rigidly tonal improvisations, within the same month.

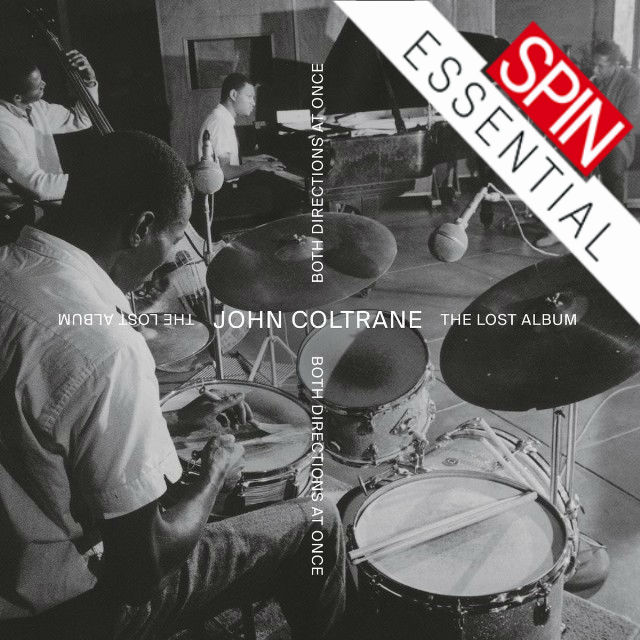

Newly released, abandoned master tapes for a 1963 studio album, found in the basement of Coltrane’s first wife Naima, provide an unusual composite of the saxophonist’s different stylistic modes in the first half of the decade. Posthumously titled Both Directions At Once, it captures of one of the greatest jazz groups of all time—Coltrane’s “classic quartet” of pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Jimmy Garrison, and drummer Elvin Jones–trying to settle on a new recorded personality, and drawing the strains of their artistry together. The contrasts of their catalogue are pushed against each other, sometimes within the same song. Fascinatingly, the March session came the day before Coltrane’s quartet united in the same studio—Rudy Van Gelder’s legendary New Jersey facility–to record with the vocalist Johnny Hartman to record a lush, self-titled collection of standards. Both sessions occurred during one of Coltrane’s least prolific periods of studio recording, which makes Both Directions at Once a particularly valuable discovery. This music, which sometimes sounds at war with itself, truly bears out the LP’s title, assigned by Coltrane’s son (and accomplished saxophonist in his own right) Ravi.

On one hand, the session include several early sketches of one of Coltrane’s greatest signature tunes from this time period, “Impressions,” which would become a springboard for a fiery 20-minute exploration live in Newport that fall. It would include a few other originals that kept with the thrust of the material the band was playing live at the time. “11383” is angular and irresolute, featuring Coltrane exploiting the noisiest, most acetic possibilities of his soprano sax. On the other hand, “Vilia”—Coltrane’s rough interpretation of an aria from Austro-Hungarian composer Franz Christian Lehár’s 1905 operetta The Merry Widow—is a piece of bright, relatively conventional swing featuring largely unprovocative improvisation. Other moments bridge the gap compellingly between the quartet’s different modes of address. Their restless take on the Nat King Cole-famous crooner “Nature Boy” exploits the similarity between the song’s minor-key melody and the mournful lead melodies in Coltrane and Tyner’s own composition of the time period. The band’s restless, modal comping around it–a signature of the quartet’s greatest work–turns the novelty standard into a mystical, loping waltz.

“11386” announces itself with a Latin groove which Jones eventually embellishes into near-total free fall, complementing Coltrane’s tremulous, sometimes Eastern-inspired figures; occasionally, he ascends into unpitched ululations reminiscent of his interplay with Dolphy at the Vanguard. There’s an exciting disparity between the straightforwardness of the tune itself and the band’s volatility in the solo sections here. “Slow Blues,” certifiably the record’s most “out” moment, follows suit. Jones and Garrison, providing a deliberate bluesy chug, start out as a control variable for Coltrane, who contorts his most tenuous pitches squeaks, screams, and sighs, and spins out his disjunct motifs into hyperactive flurries. Jones is also worth tuning into here, deceptively maintaining a sense of steady groove even when his kick, snare, and ride start to relate to the downbeat only in the loosest possible sense.

Experimenting with technical tricks, assuming different voices, and meeting different material on its own terms fascinated Coltrane. Both Directions At Home, in its odd pluralism, speaks to Coltrane’s humility as a stylist, and the reason why he is revered by jazz fans of all persuasions, including anyone who only knows the bare minimum number of albums. If it’s not Giant Steps, the album that type of casual Coltrane fan knows is A Love Supreme. Both Directions at Once isn’t definitely isn’t Supreme, but it enhances our understanding of how that group of musicians came to make it.