It’s next to impossible to turn on the radio or press play on a Spotify playlist without hearing a fragment of melody, line of lyrics, or seemingly novel chord change that wasn’t previously used in some older song, lodged in a back corner of your musical memory. Whether by intentional homage and sampling, unconscious borrowing, or outright theft, we are living through a truly postmodern age in pop music. (Ask the Fray and Fastball, of all bands, if you don’t believe it.) And if you were paying any attention to popular rock music of the last 15 years, there are few musicians whose explicit songwriting influence you would have heard more often than Tom Petty‘s.

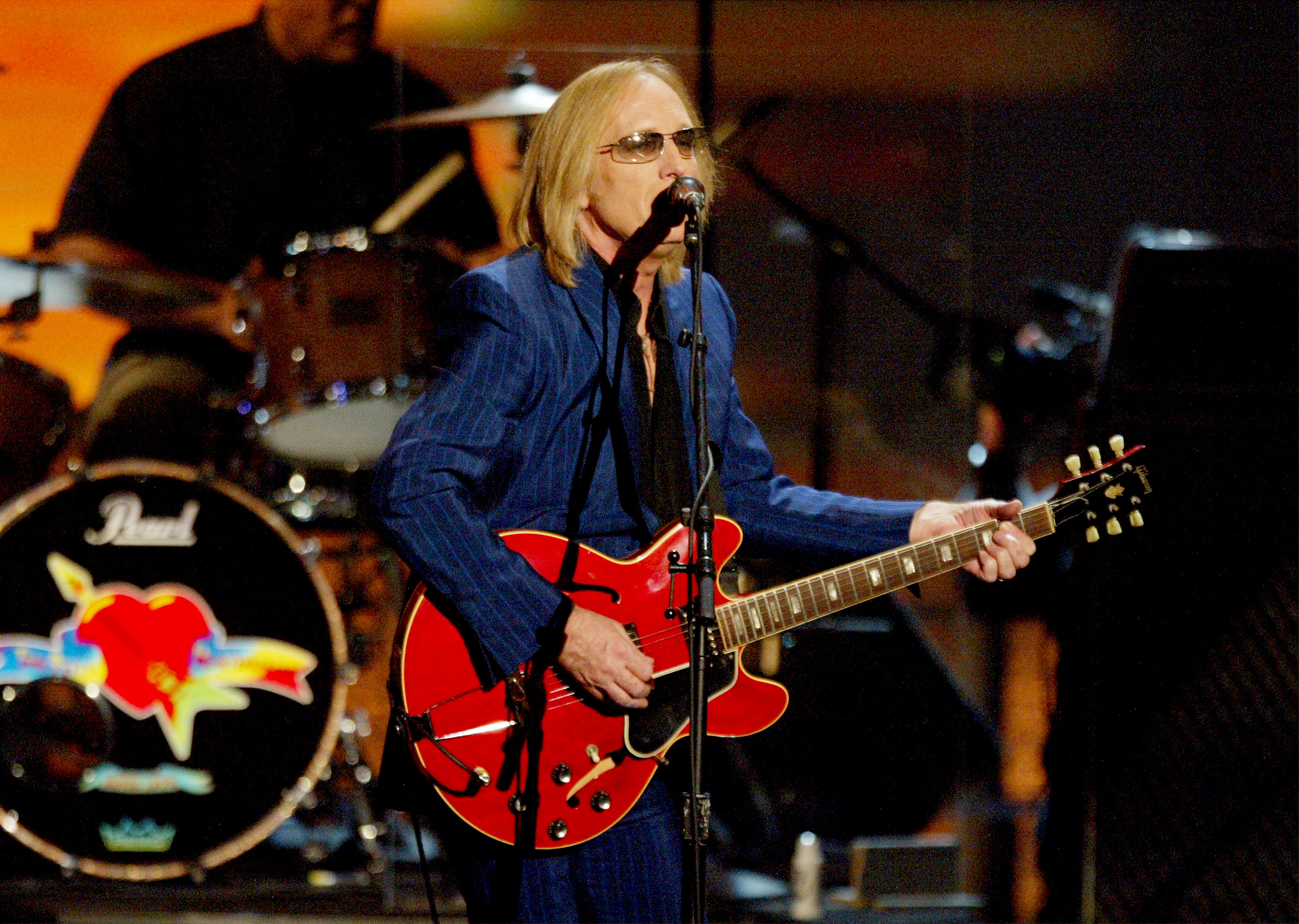

Petty, who died at 66 years old on October 2, 2017, had a way with simplicity. There’s a reason pretty much everyone likes him: He rarely used more than a small handful of chords in a song, rarely wrote lyrics that weren’t populated by archetypes and animated by universal truth. There’s nothing about a song like “I Won’t Back Down” that situates it in a particular time or place, no reason not to imagine yourself as the subject of Petty’s mantra to perseverance. In a less talented musician, you might call this tendency vagueness. But Petty’s work crackles with life because of this broad applicability, not in spite of it. He located something elemental in the heart of the rock song–something that allowed a performer like Grace Jones, whose identity and aesthetic sensibility could hardly be more divergent from Petty’s, to take one of his signature hits and fully make it her own.

These are the qualities that made Petty’s work irresistible to a generation of rock and pop stars that were raised on his music. Below, you’ll find three relatively recent songs that wear their Petty influence on their sleeves. That isn’t to say these artists stole anything from the late master. It’s just that if you’re trying to write catchy, immediate songs about love and America, on a guitar with a tight backing band, you might come out sounding like him whether you intended to or not.

The Strokes – “Last Nite” / “American Girl”

According to a Rolling Stone interview with Petty in 2006, the Strokes once owned up to their wholesale appropriation of the intro to “American Girl” for their own breakout hit. We can’t find firsthand evidence of the admission, but the two passages are so similar that it would be impossible for Julian Casablancas and the gang to deny it. Each song begins with a slightly dirty electric guitar chiming out a single note. In comes a barebones kick-and-snare drumbeat, swinging hard. After a few bars, the bass and another guitar come in with a counterpoint that provides some harmonic motion and the tension to hurtle you into the first verse (which begins, by the way, with the frontman singing the title of the song).

That’s where the similarities are most obvious, but they don’t end there. Think about the way that Casablancas and Petty’s narrators are both addressing a woman in the third person, who feels disillusioned and alone despite having arrived in some glamorous locale. In “Last Nite,” she’s “been in town for just about fifteen minutes now,” and feels “so down / And I don’t know why”; in “American Girl,” she has a “desperate moment” alone on a balcony, thinking about a guy in the place she left behind.

The fact that it was the Strokes doing the ripping–probably thought of as the single coolest rock band in America at the time–speaks further to the timeless relatability of a guy who’s work wasn’t exactly au courant in the early 2000s. In the same Rolling Stone interview, Petty was good-natured about it all. “The Strokes took ‘American Girl,’ and I saw an interview with them where they actually admitted it,” he said. “That made me laugh out loud. I was like, ‘OK, good for you.’ It doesn’t bother me.”

Red Hot Chili Peppers “Dani California” / “Mary Jane’s Last Dance”

That Rolling Stone interview from 2006 wasn’t even primarily about “Last Nite;” that song came up as a tangent when the magazine contacted Petty to talk about an even more blatant rip: “Dani California,” the lead single from Stadium Arcadium, Red Hot Chili Peppers‘ bloated double album from earlier that year. Rather than look to Petty’s early work for inspiration as the Strokes did, RHCP went straight to one of his last big hits. The verses of “Dani California” are big and gaudy homages to “Mary Jane’s Last Dance,” from the three chords that underpin them, to the rhythms in which those chords are played on the guitars, to the lyrics about a woman and her parents and the place that they’re from, and the conversational way each singer delivers them. Here’s Petty’s opening couplet, for instance:

She grew up in an Indiana town

Had a good lookin’ momma who never was around

And here’s Anthony Kiedis’s:

Getting born in the state of Mississippi

Papa was a copper, and her mama was a hippy

It was initially reported at the time that Petty was considering a lawsuit, but he evidently chilled out about it at some point. “The truth is, I seriously doubt that there is any negative intent there…I don’t believe in lawsuits much,” he told Rolling Stone. “I think there are enough frivolous lawsuits in this country without people fighting over pop songs.” Maybe he realized he was in good company: after its Petty theft, “Dani California” goes into a guitar solo that’s practically a note-for-note recreation of Jimi Hendrix’s “Purple Haze” riff.

Sam Smith – “Stay With Me” / “I Won’t Back Down”

While “Last Nite” and “Dani California” incorporate both the musical building blocks and the outward stylistic signifiers of Petty’s songs, Sam Smith‘s “Stay With Me” is related to “I Won’t Back Down” on a purely compositional level. In terms of instrumentation, tempo, and general vibe, the two songs sound almost nothing alike, meaning the similarity might be a little more difficult to hear if you’re not used to thinking like a musician.

The similarity hinges on Smith’s chorus, ie. the part where he and his backup vocalists sing “Stay with me / ’cause you’re all I need.” Forget “’cause you’re” for a second, and focus on the way he breaks the rest of the words into two chunks of three. He starts high, with “stay,” takes a small step down for “with,” and a slightly bigger step down for “me.” After a pause for “’cause you’re,” he takes “all” on the note he left off with, makes his biggest step down yet for “I,” and stays there at the bottom for “need.”

Now listen to the beginning of “I Won’t Back Down,” where Petty sings “I won’t back down / No I won’t back down.” Try to imagine it a little slower, with gospel singers backing Petty like the ones Smith has. Can you hear it? The first “Won’t back down” is situated within Petty’s key (G Major, if you’re wondering) in exactly the same way that “Stay with me” is situated in Smith’s (C Major), with exactly the same downward melodic motion and exactly the same rhythm. The second “Won’t back down” is directly analogous to Smith’s “All I need” in all of the same ways. Petty bridges the two chunks with an offhanded “no I,” just as Smith does with “’cause you’re.”

Fortunately, if the music talk is confusing and you’re having trouble hearing it, a YouTube music theorist going by Fercho 21 created the below video, which futzes with the tempo and key of each song enough to make the comparison obvious for even a casual listener.

Smith’s is the only case here that feels less like an intentional tribute than a (perhaps unconscious) rip-off, and accordingly, it’s the only one over which Petty chose to seek a songwriting credit. In 2015, he and his cowriter Jeff Lynne (of Electric Light Orchestra and Traveling Wilburys fame) came to an agreement with Smith and his cowriters to add their names to the “Stay With Me” credits, earning Petty and Lynne a percentage of its publishing royalties. Smith and his team wrote that the similarities were a “complete coincidence,” and again Petty responded affably. “Let me say I have never had any hard feelings toward Sam,” he wrote in a statement. “All my years of songwriting have shown me these things can happen. Most times you catch it before it gets out the studio door but in this case it got by. Sam’s people were very understanding of our predicament and we easily came to an agreement.”

Bonus: The War on Drugs

While there’s no single War on Drugs song that explicitly evokes a particular Petty composition like the three songs above do, it’s worth noting that one of 2017’s best and most acclaimed rock albums is thoroughly immersed in the Hearbreakers’ gospel. Adam Granduciel’s throaty whisper evokes both Petty and Bob Dylan, Petty’s own most obvious forebear as a singer. His songs take an even wider angle on their subjects than Petty’s do, to the point that they are almost metaphysical, and his spacious sonics reflect this, untethered as they are from the earthbound bar band tradition. But it’s hard to imagine songs like “Nothing to Find” or “Pain”–their humility, their transcendently nonspecific yearning, their free intermingling of rootsy guitars and synthy studio sheen–without Petty’s catalog before them.