A smooth-chested wrestler in a towel and a leer grabs the mike. Val Venis, with an “i”, is an ex-porn star who likes to brag about his penis. In the World Wrestling Federation, this makes him a good guy. He points to his johnson and to his foe’s girlfriend, Jaclyn, and says, “She’ll soon be looking for bigger pastures.” Venis, also known as “The Big Ballbowski,” then lays Jaclyn’s massive silicone chest across his knees and spanks her butt. Scores of preteen and just-teen males howl with delight.

In Albany, New York, near the end of the summer, the WWF has come to the Pepsi Arena for a sold-out Saturday-night show. Banners from minor-league hockey teams and a half-dozen local colleges hang about the crowd of 10,000. In Row D, 50 yards from the ring, an extended family shovels popcorn into their already overfed mouths. The doughy, red-cheeked eight-year-old to my left will be heavy when he grows up. He sucks down his grub with gusto, till the MC announces, “X-Pac!”

The red-and-black-suited X-Pac, one member of a WWF faction called D-Generation X, races down the aisle to mob approval, his long black locks streaming. Skinny for a wrestler, and hyper, he humps the air and makes an X across his inner thighs with rapid-fire karate chops, giving the crowd the phallocentric “DX” gang sign. My sugar-shocked neighbor vaults his 90 pounds upward and hammers his prepubescent package, frantically miming the sign right back. His excitement peaks when X-Pack enters the ring to deliver the DX tagline. “Bitch,” X-Pac tells his pretty-boy opponent, the flaxen-tressed Jeff Jarrett, “me and Albany have two words for you.” He pauses for effect, and then my spasming little pal joins the rest of the audience in a jubilant chorus: “Suck it!”

A few weeks ago, X-Pac pissed in Jarrett’s gleaming white boots; in return, “Double J” smashed a guitar over X-Pac’s swarthy head. Tonight, X-Pac pins Double J, winning the latest episode of the feud. As Jarrett leaves the ring, boys rush the barricades, as they do after every match, and one dumps a beer on Jarrett’s head. A nearby 16-year-old named Darren has a dog collar and a bald, pink head, but there’s a scrap of blond moss an inch behind his right ear. Those WWF fans who are old enough to shave can’t seem to do it right. “Why do you watch this instead of World Championship Wrestling?” I ask, referring to the other of wrestling’s two big leagues. Darren’s friend answers first. “[The WCW’s] way too censored,” says Jordan, 17. “They say butt instead of ass.” Darren’s reason is simpler. “Stone Cold,” he mutters. “Definitely Stone Cold.”

Also Read

The Greatest WrestleMania Entrances

“Stone Cold” Steve Austin is the main event here, as he is every night. The sight of his bald skull, goatee, and black leather vest nearing the ring produces the night’s biggest “pop”–wrestling for “reaction.” When Austin defeats a masked titan named Kane with his “Stone Cold Stunner” move, the arena roars till my ears buzz. The WWF’s meal ticket begins with his cocky, lurching stroll back to the dressing room, holding his World Championship belt aloft, then stops. He rushes back between the ropes, as if he forgot something. He climbs the turnbuckle, and flips the whole world the bird. The crowd returns his trademark gesture 20,000-fold. A sea of giant foam middle fingers rises to salute him.

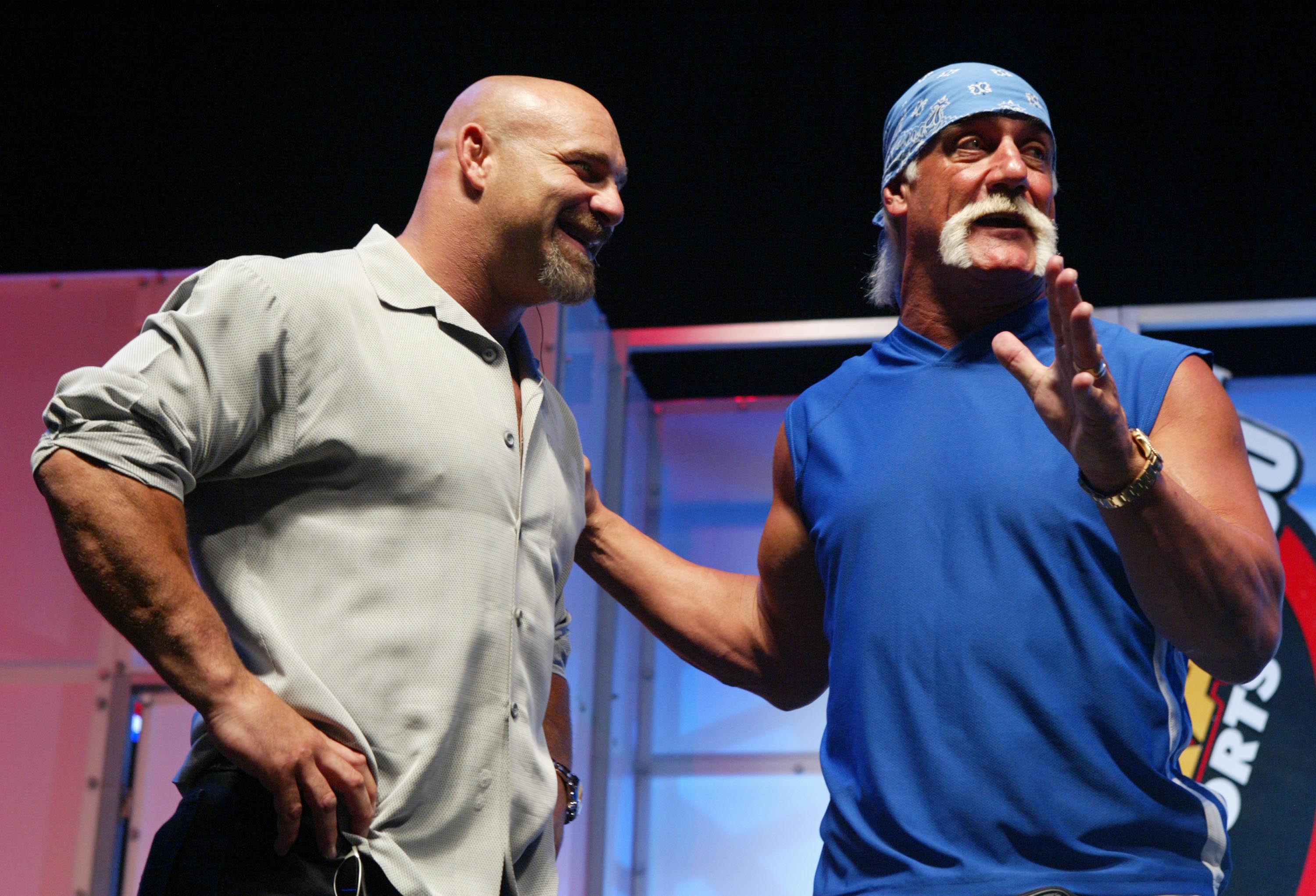

Professional wrestling has rebounded from an early-’90s slump to become a $400 million business that can outdraw the NFL on TV. Two of the three highest rated shows on cable are wrestling; three-and-a-half-million households view an average episode of WCW’s Nitro or the WWF’s Raw. Combined, there are over a dozen hours of televised wrestling each week. In this, the Year that Wrestling Broke, 33-year-old Steve Austin would seem to be the face of the moment–except there’s another, very similar mug contending for the honor. Before Steve Austin led it back to parity, the WWF had been battered by its better-funded rival, Ted Turner’s World Championship Wrestling. Now, as part of its strategy to stop the renewed momentum of the WWF , the WCW has hyped its own black-clad antihero, a bigger, more bionic Steve Austin named Bill Goldberg. Inside the ropes, wrestling’s battles may be scripted, but outside them there’s a death match between a megacorp that wants to make wrestling safe as milk and a family-owned firm that’s found new life by flipping off grade-schoolers.

In 1982, Vince McMahon bought the WWF, the Northeast’s wrestling syndicate, from his father. Using cable television–and Hulk Hogan–McMahon exterminated the competition, the two dozen regional firms that had run the sport as a patchwork of local fiefdoms since World War II. He took the WWF nationwide, and made it interchangeable with professional wrestling.

The golden era peaked with Wrestlemania III, in 1987, when 93,000 filled Michigan’s Silverdome to see Hogan vanquish Andre the Giant. But the golden era ended in 1992, in court. During the federal trials of two steroid-happy doctors, witnesses claimed that 90 percent of the WWF was using. Though McMahon denied everything, FEdEx receipts were produced, and big names were named, such as Hogan and the Ultimate Warrior. The New York Post detailed allegations made by WWF “ringboys” that two officials were pedophiles. McMahon sued, then dropped the suit and suspended the accused execs. TV ratings fell to a 2 share.

Before scandal could send it back to its pre-Hulk limbo of Saturday-afternoon syndication, wrestling regrouped. McMahon’s witness-box admission that the fake sport wasn’t a sport ultimately proved liberating. The faker issue became moot, and wrestling became a non-sport in 49 states, exempting it from certain taxes and drug regulations. Simultaneously, hard-core fans drew strength from an upstart Philly promotion called Extreme Championship Wrestling. Porn queens passed as “celebrity guests,” while ECW’s mooky acrobats beat each other with barbed-wire and baseball bats. Too many “caning matches” and crucifixions got it booted from cable, but during its mid-’90s heyday the ECW nourished pro wrestling with fresh story lines and a higher-flying style.

More important for the “sport”, Ted Turner’s World Championship Wrestling, after foundering for five years, in 1994 hired a new executive vice president named Eric Bischoff, a former announcer from the promised land of wrestling’s frozen chosen, Minnesota. He, in turn, hired Hulk Hogan from the Word Wrestling Federation (for $5 million a year), followed by the rest of the WWF’s top stars and a dozen of the ECW’s. He even stole the WWF’s announcing team. When “baby-face” Hogan changed into an evil “heel,” and Turner started airing the WCW’s Nitro live on the TNT network on Monday nights, opposite the WWF’s longtime Raw berth on USA, wrestling had recovered. The WCW got healthy first; in mid-1996, the Atlanta-based league began an 83-week run atop the ratings.

While Bischoff stirred the soap opera, he also changed the rules of wrestling’s ancient morality play. “If you look at action movies,” says Bischoff, “most of the characters who people like have a little gray in them.” In Bischoff’s postmodern soap, the bad guys became the stars and the heroes became antiheroes. The anti-heroes with the highest Q ratings were the members of the New World Order, WCW’s outlaw league-within-a-league, led by Hogan and Bischoff himself. This past spring, with the NWO growing stale, Bischoff split it into warring factions, complete with gang colors–Hogan’s black-and-white NWO Hollywood, and pro basketball dropout Kevin Nash’s red-and-black NWO Wolfpac.

But there were limits to how edgy Bischoff would get, because he wanted to expand wrestling’s audience, and make the once-grotty sport acceptable to advertisers. He hired an outside ad firm to buff the WCW’s image, and booked mainstream celebrities such as Karl Malone and Jay Leno to draw the unconverted. He also kept it clean, as per Turner’s orders. The WCW wouldn’t eve let one its wrestlers call himself “Skank.”

Bischoff’s efforts have put some dents in wrestling’s trailer-park stigma. Lately, upscale clients such as mutual funds have rushed to buy advertising time once occupied only by Slim Jim. Revenues have grown tenfold since 1994, and the cost of a Nitro spot has risen 70 percent in two years. Together, the WCW and the WWF attracted $55.3 million in advertising last year, and the cash flows faster all the time.

But, as Jerry Solomon, an exec at the SFM Media ad agency, points out, “it’s just a case of the ratings getting high enough that people can rationalize what they’re buying.” The guys who purchase commercial time for their clients are aware that ten million people watch wrestling each week, but most haven’t watched the shows themselves to see why, and most don’t know there’s a difference between the two leading products. They don’t know about Steve Austin.

In 1995, 6’2″, 250-pound “Stunning” Steve Austin was half of a pair of WCW heels called the Hollywood Blondes. Though they were popular tag-team champs, Bischoff split them up. Austin claims that a certain older star–he means Hogan–convinced management he’d never amount to much. When Austin tore his triceps, Bischoff let him go. Austin recalls the moment with relish. “He said, ‘Steve, you go out there in your black trunks and black boots, and there’s not a whole lot I can do to market you.'”

After a brief stint in the ECW, where he cut off his stringy blond locks and learned the bankable art of running his mouth, Austin surfaced in McMahon’s WWF in early 1996. To his chagrin, his new boss handed him a pair of emerald trunks and said, “You are now ‘The Ringmaster.'” Austin wasn’t impressed, and neither were the fans. The Ringmaster died, unmourned, after six months.

One day a downcast ex-Ringmaster was channel-surfing when he chanced on an HBO special about serial killers. Late in 1996, “Stone Cold” Steve Austin appeared. His gimmicks were 1) not giving a damn about authority, and 2) a heap of potty talk. He proved he could flap his gums with a career-making flip remark. After beating Jake “the Snake” Roberts, known for preaching by day and hitting strip clubs at night, Austin mocked the Snake’s piety. “Talk about you psalms, talk about your John 3:16,” he scowled. “Austin 3:16 says I just whupped your ass.” Austin 3:16 T-shirts flooded the high schools. Accustomed to being a heel, Austin found that the worse he acted, the more the headbangers loved him.

At first, McMahon and the USA Network, WWF’s TV home, tried to curb Austin’s behavior, especially his permanently erect middle finger. But by late 1997, a year into the WCW’s rating reign, McMahon changed his mind. The whole WWF began to mimic Austin’s appeal to the teen male id. The turning point may have been an ECW-style stunt in which Dustin Runnels staked his wife on a match and lost her, and Raw aired footage of his foe consummating the bet. With the launch soon after of the D-Generation X gang, a crotch-grabbing one-up of the New World Order, the WWF had officially copped an attitude. McMahon marked the change by raising a piratical black flag at the company’s Connecticut headquarters.

In the born-again WWF, everyone’s NC-17. Feeling Goth? A fanged porker named Gangrel drinks a bucket of blood before each match, letting the gore stream onto his ruffled Meat Loaf prom shirt. Also working the undead beat is the Undertaker, Austin’s nemesis, a tower of pallor devoid of feeling, though it probably hurts when he rolls his eyes back in his head like he’s always doing. The Godfather, meanwhile, is an all-too-mortal pimp. Daredevil ECW vet Mick Foley, best known as Mankind, a leather-masked geek who drags a trash bin full of painful tools to the ring, also morphs into Cactus Jack, a kind of hillbilly Tonto with beer tits and missing teeth, and Dude Love, a dumbass hippie. Small wonder that last fall, in her final days as head of the USA Network, Kay Koplovitz called McMahon and asked him where the wrestling superheroes of the eighties had gone. “Those days are over,” gloated McMahon. “That milquetoast era of good guys and bad guys is gone.”

Dave Meltzer, editor of the pro circuit’s newsletter of record, the Wrestling Observer, says he doesn’t expect any wrestling promoter to have a social conscience. McMahon is simply a compulsive opportunist, consumed by competition. Obsessing aloud about “the billionaire” Ted Turner, he peppers Turner’s league with baseless lawsuits and dispatches D-Generation X to Nitro events in hopes of a Raw photo op. He loves to jump on camera and take a Stone Cold Stunner, or call a woman a “bitch” all in the name of ratings. “People generally know that Vince is an asshole,” reports Meltzer. “That’s why he plays one on TV.”

Because of wrestling’s long bond with youngsters, Eric Bischoff blasts his rival’s newly dark direction. “The idea of competition is what every pimp on every street corner knows,” he fumes, with the moral authority of a promoter whose biggest female star has posed for Playboy. “Sex sells, especially to kids. Sooner or later the people in media and advertising are going to realize what [the WWF] is doing, and I’m afraid we’re all get lumped in the same bucket of shit.” Bruno Sammartino, a demigod of the squared circle who sold out Madison Square Garden 185 times in the ’60’s and ’70’s, quit his job as a WWF announcer ten years ago believing the steroid-riddled sport had hit rock bottom. He decided he was “way, way off the mark” when his son made him watch Stone Cold on Raw recently. “I’m ashamed to see that the business I was associated with has come down to this,” he says.

McMahon, meanwhile, revels in the controversy. The “TV-14” chiron that graces Raw, and not Nitro, is more a promise than a warning. “Quite frankly, I wouldn’t mind if the rating were a little more harsh.” To McMahon, critics are grousing because his underdog league has grabbed the creative initiative away from the WCW, and now Turner’s lackeys are playing catch-up. Their best idea of the past year, says McMahon, was his. “Let’s face it,” says McMahon, “Goldberg is a Stone Cold rip-off.” Austin chimes in, “If Goldberg’s not trying to copy me, I’d hate to see what would happen if he did.”

[featuredStoryParallax id=”233481″ thumb=”https://static.spin.com/files/2017/03/TrumpAustinGetty-1490994313-300×153.jpg”]

The backstage corridors of the Rushmore Plaza Civic Center are a maze of the semi-famous. Framed photos of Anne Murray and Air Supply line the peach-sherbert walls, and each fork in the cinder-block halls only leads to another.

One such passage ends in a softly lit, elbow-shaped lounge, a holding cell for the mid-range celebs of Rapid City, South Dakota. But at 4:30 on an August Monday afternoon, the stars on the couches are bigger than usual. Huge men sit in the half-light, without speaking, and in their midst, across a table where party snacks should be, sprawl the 291 pounds of WCW heavyweight champion Bill Goldberg, face down. A pony-tailed chiropractor pauses his taffy-pull of the 6’3″ Goldberg’s epic back, while his other patients wait stoically. The vibe is grim and dental.

Next door, in the fluorescent brightness of a commissary, members of World Championship Wrestling’s 60-man traveling troupe ring a half-dozen folding tables. They play cards and talk. A few gnaw at the fat-free ovals of beef that feel the nearby warming trays, or ladle strawberry goo from the Costco-sized jugs. When Goldberg walks in freshly adjusted but still palpating his collarbone, one behemoth approaches and extends a paw. Goldberg shakes it. Having said hello, Kevin Nash, “Big Sexy,” heads for a chair across the room. At another table, Vincent, the NWO’s black valet, plays a hand with fellow bad guy Brian Adams and soon-to-be bad guy Stevie Ray. (The NWO’s white valet, the Disciple–formerly Brutus Beefcake–who with his leather chaps and waxed chest could be a Village Person, is MIA.) The Nitro girls, WCW’s cadre of pneumatic dancers, are not seen, but can be heard, practicing to jock jams at stadium volumes.

Goldberg has wrestled almost all of them except the Nitro girls, and quickly. Most of his bouts are the extra-short routs called “squashes.” In an unbeaten string stretching back a year and 130 matches, the bald, goateed Goldberg has been promoted as invincible. While he has flashed an uncoachable charisma, Goldberg hasn’t had a chance to show many moves. One of his finishers, “The Spear,” is, after all, a tackle. “People don’t come to see me do headlocks and arm-drags and clotheslines,” says Goldberg with a huff. “They come out to see me demolish guys, and I’m more than happy to oblige.”

Thirty-one-year-old Bill Goldberg grew up in Tulsa, Oklahoma, the driven, rowdy, son of a violinist and a Harvard-trained gynecologist. As an all-SEC noseguard for the University of Georgia in the late ’80s, Goldberg became known as a trash-talking, hyperaggressive, junkyard dog who’d do anything to get the ball-carrier. A “warlord,” Ole Miss Billy Brewer called him.

But the NFL is only for the exceptional and the lucky, and, at 275 pounds, Goldberg wasn’t even that huge. He got cut from the Rams in 1990 and again in 1991, and he went to play in the short-lived World League. The next year, the Falcons brought him home to Atlanta, where he played 14 games over three injury-plagued seasons. When he tore his stomach in half, he had to hang up the cleats.

Goldberg knew a handful of wrestlers from working out at Main Event, a gym owned by WCW stalwarts Sting and Lex Luger. Plenty of football players had made the transition to wrestling, and the guys at Main Event always asked Goldberg when he was going to follow suit.

It took seven years to convince him. His post-football options limited, Goldberg finally decided what-the-hell, and waxed off his tummy fur. After a year of training, he made his broadcast debut on September 22, 1997, squashing a beer-bellied journeyman named Hugh Morrus in two minutes, 30 seconds. There were no “Daryll” style chants of “Gold-berg” yet, but Bill did a standing backflip, and got a big hand from the crowd. The announcers asked, “Who is this guy?” and Goldberg worked the enigma angle by refusing the all-important post-match interview. Within a month the bosses were “pushing” him, in industry terms, as a laconic, unstoppable, mysterious loner. “The only things missing are the bolts in his neck!” enthused an announcer in February. He was the WCW’s creation, all right–Goldberg thinks his league wanted to homegrow a supergolem because so many of its other stars were borrowed. This July, in front of 41,000 at the Georgia Dome, he became the WCW’s top dog by taking down the franchise. Hulk Hogan, in a TV match that earned a 6.9, the highest quarter-hour rating in the history of wrestling on cable.

Goldberg’s next task could be avoiding overexposure. “[The WCW doesn’t] want to run me thin,” he says. Still, the league couldn’t stop a media romance with his ethnicity. At least a half-dozen current wrestlers are Jewish, including a high-profile heel who begged me to not out him for fear of fan abuse. Goldberg isn’t the first Jewish wrestler, but he’s the most out-front, because he uses his echt-Hebraic given name. Articles detailed his early plans to call his character Mossad, or how he’d toyed with putting a Star of David on his trunks. Former Falcons teammate Chuck Smith calls “Goldy” a “hardass backwoods white boy,” but he’s more like a Jew from the tribe of Butch. No fans have yet hurled any anti-Semitism his way, and if they do, “I’ll have them thrown out,” he promises, “’cause I don’t trust myself. I’d rip their heads right off their shoulders.”

The fans in Rapid City, South Dakota, would never be so rude. For one thing, these prairie dwellers are surprised, but not fazed, to learn that a man named Goldberg is Jewish. “Huh?” says one. “I figured he was German.”

By showtime on Monday, the 8,500-seat Rushmore Plaza is still not full. The organizers have to paper the house with 1,000 free tickets. The WCW’s director of marketing, Mike Weber, surveys the scene and tries to explain. “Only two people have over sold out this place–Garth Brooks and Elvis Presley. No one lives here.” It’s true. The fans who are here have driven hours from every corner of the empty spaces. I meet Indian kids from the Crow Reservation in Montana, and the Sioux lands near Wounded Knee. The red folding chairs by the ring swell with baseball cap-wearing blonds from the checkerboard farmland of the Dakotas.

These pilgrims wield signs. Being less than dewy seems to enhance Hulk’s heel appeal. Signs insist that HOGAN NEEDS VIAGRA, HOGAN WETS THE BED, HOGAN NEEDS ROGAINE, and at least one of them is right. But most of the signs salute Goldberg. They say, WHO’S NEXT? a Goldberg catchphrase, or THE WORLD FEARS GOLDBERG. Groups of eight boys take one letter of his name each, spraying their chest with golden glitter from G to shining G. They’re here to see the Man, and they’re a wholesome bunch who apologize for cussing when they gush, “He’s one mean son of a bitch.”

Out in the hallway at the concession stand, as Lex Luger and Bret Hart grunt through an old-school marathon back in the arena, Chris Robinson buys a red Wolfpac tee. He’s already wearing a Goldberg shirt. He works at a video store in Manitoba, a 14-hour drive away, where he and his coworkers talk about nothing but their “soap opera,” wrestling. Chris tells me that Bret “The Hitman” Hart can’t lose tonight or for three years because it’s in his contract, and that Hart will break Goldberg’s string before he turns on Hogan and joins the Wolfpac. How does he know this? “Because I’m on the Internet all the time! There’s a guy who, I’m telling you, can predict it. He got Hart’s contract!” The Web, that fount of conspiracies, was made for the hidden agendas and endless speculation of wrestling. According to one published report, 96 percent of the top 1000 sport sites on the Web are devoted to wrestling. Some reportedly get 200,000 hits a day.

Robinson hurries back to the arena floor, where, not five minutes later, Lex Luger cancels Hart’s no-lose contract, and sends the Web re-spinning. Soon, it’s time for the main event.

“Rapid City, South Dakota,” bellows famed ring announcer Michael Buffer, dragging the r. “Arrre you rrready to rrrumble?” The crowd starts chanting “Goollld-berg” upon hearing the first martial notes of his familiar Wagnerian intro theme. “Wearing black and weighing in at 290-one-half pounds, this is the man who has been victorious in 130 consecutive matches. This is the man who has captured a cult following like none other in wrestling history…This is Gooooldberrrg!”

The “pop” is literal when Goldberg enters, in black trunks, gloves, and elbow pads. He assumes the position for the most painful and over-the-top entrance in pro sports. He stands with his eyes downcast–and waits. Sparklers erupt all around him, and for 20 second, six-foot streams of silver sparks shower onto his skin. When it’s over, he exhales a mongo bong-hit of poison smoke through his nose. Later, I ask him what fireworks taste like. “Shit. They actually taste like fireworks. Not that I go around tasting fireworks.”

The harshest toke gives way to a ritual posedown. Goldberg opens his mouth in a wordless scream, flexing his whole body. A left uppercut, a right cross, two slaps to the head, and a pec-ripple later, and he’s down on the ramp to wrestle a giant Polynesian with hockey hair named Meng.

Goldberg and Meng pound each other until Goldberg takes a well-timed roll under the ropes and into the clutches of Hogan’s black-and-white goons. They beat him till the red-and-black cavalry comes. Kevin Nash and the Wolfpac race to the rescue, and Goldberg slips back into the ring. He escapes from Meng’s Tongan Death Grip to spear, jackhammer, and otherwise squash him.

But while he’s contorting his face in a victory grimace, sticking his tongue out like that other nice Jewish boy, the one in Kiss, the cowardly Hogan sneaks up and creases his back with a folding chair. By the time Goldberg clears his head and turns around, Hogan has disappeared. There, instead, stands Kevin Nash. Goldberg pantomimes a look that says his would-be friend has betrayed him, then wastes Nash with a Spear.

As the angry loner heads for the dressing room, Nash grabs the mike and shouts, “Anytime Goldberg wants a red-and-black shirt, he’s got one.” South Dakota roars its approval of this emerging story line, in which misunderstandings keep the solitary antihero from joining the people’s favorite subcult. Goldberg hopes to leverage a clause in his contract that says he never has to join any of the faux gangs, but except for the outcome of the matching, nothing can be predicted in wrestling.

Meanwhile, Vince McMahon’s ventures continue unabated. He’s hawking everything from monster trucks to action figures, from D-Generation X trading cards to Stone Cold pool cues. He’s even purchased the Debbie Reynolds casino in Las Vegas, with plans to convert it into a grappler theme park with gambling.

But the gold rush may be sputtering. The WCW reclaimed the ratings lead with Goldberg’s win over Meng, and has kept it since, mostly by recycling sunlamped seniors such as WWF alum the Ultimate Warrior. Merchandise sales at live WWF events have fallen $2 per person, meaning Stone Cold shirts may have already peaked as the teen-male armor of choice. They day after Albany, the WWF traveled to the 4,500-seat Catholic Youth Center in Scranton, Pennsylvania, a venue that the WWF has played since the days of Vince McMahon, Sr. In the first sign that someone has noticed the clash between content and audience in Junior’s product, a local bishop banned the WWF after the appearance; 45 percent of the Scranton crowd had been children.

McMahon responded to the bishop by grumbling about the First Amendment. Lest anyone, however, think it was McMahon’s lifelong goal to give eight-year-olds the right to scream “suck it,” he would change his attitude tomorrow if that’s where the money led. “It’s important to remain flexible,” he states, “and to give the public what they want. If the public prefers more of a conservative shift,” McMahon says with a shrug, “then that’s the way we’ll go.”

This piece originally ran in our December 1998 issue. In honor of this weekend’s Wrestlemania, which features Goldberg in the main event, we’ve reproduced it.