This is Part Four of SPIN‘s November 1985 cover story, “The Meaning of Bruce,” wherein we asked seven writers to consider the Springsteen phenomenon. (Check out the other essays, by Glenn O’Brien, Richard Meltzer, Tama Janowitz, Rich Stim, Scott Cohen, and Eric King, respectively.)

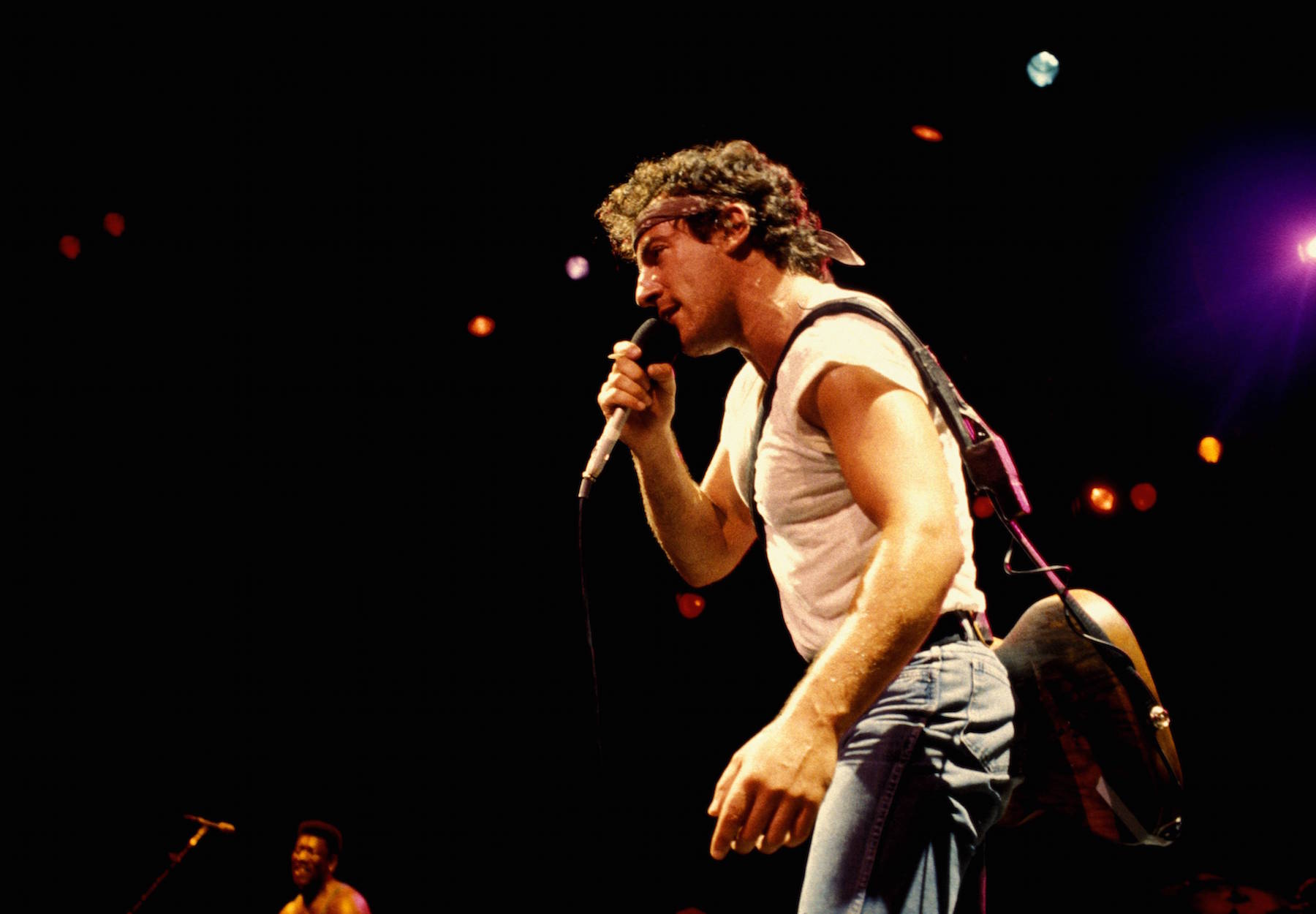

What is refreshing and encouraging about Bruce Springsteen is his ability to translate both the form and some of the content of the blues. Springsteen is an American shouter, like the black country blues shouters from Leadbelly on, with an ear to James Brown and Wilson Pickett.

Springsteen’s shouter style is apparent in “We Are the World,” while the lyrical social consciousness of Born in the U.S.A. added yeast to his public and commercial persona. He’s the voice of working-class youth, we have heard, and there’s much truth in that. Would that more young Americans free of the double maw of working-class economic insecurity and lack of education were so clear as Springsteen as to what being born in the U.S.A. yokes working-class whites (and blacks) to. And even though Springsteen himself, as a superstar, must continually affirm the myth of being “free, white, and 21,” his willingness to dispute that illusion in the real America is healthy and important.

[featuredStoryParallax id=”152241″ thumb=”https://static.spin.com/files/2015/07/GettyImages-85853646-250×250.jpg”]

Also Read

SAME AS THE OLD BOSS

What makes Springsteen so convincing, besides his appropriation of the blues shouter’s voice, is the nature of his concerns. The often tragic poetry of the blues is packed with reflections on a brutal society in which the singers are victims, lonely, broke, and hungry. Springsteen describes a visible, living America with its obvious flaws, a real world. His American blues are solid and not given to minstrelsy. Their authenticity is no doubt due to his understanding of what old blues songs, and Woody Guthrie’s too for that matter, mean.

What amazes is the whole “Boss” thing. It creates a false relationship to traditional blues players that even Springsteen himself doesn’t desire. Springsteen knows he’s not Joe Turner, “The Boss of the Blues.” He has also demonstrated that he feels closer to the common people than to the “bosses.” Springsteen’s persona, for example — the working-class youth checking out reality — would condemn the individuality embodied by the trend-making elite who retard music lovers, as separate and unequal as we are.

One wonders, though, at the flush of the Springsteen explosion revved up by his recent Born in the U.S.A. tour. How far can he go in refining, raising, and deepening his vision? Has he the resources (consciousness and commitment) to progress further or to at least maintain his pitch on some important level? We should know by now that no artist, no matter how popular, can completely buck the forces of commerce, or his career, even his name, will disappear. We have seen Stevie replaced by Michael, who in spite of all his Victory has still been condemned for daring to try and make all that money. Prince and Boy George swiftly rose to Commerce’s rescue.

The United States and the world at large are at a crossroads. Springsteen sings about one direction, though his songs are more reaction than concrete analysis or exhortation (one journalist, however, did mention Springsteen’s “preaching” during his Jersey shows). A shouter such as Springsteen could easily become a significant ingredient of a critically important public drama, here in the U.S.A.!