It is October 1986, and Michael Jackson is holed up in a West Hollywood recording studio trying to complete the follow-up to Thriller, the best-selling album of all time. The new record has been in production for almost a year already and is long overdue. There have been problems.

The last four years have not been a good time for Michael Jackson. Since Thriller and the Jacksons’ disastrous Victory tour, he has managed to generate the most powerful backlash in the history of popular entertainment. There have been bitter family feuds, an acrimonious rift with the Jehovah’s Witnesses, broken friendships with Diana Ross and Paul McCartney, and the burden of a celebrity so unmanageable that it drove him into isolation. Even in seclusion, reports of his plastic surgery, his private menagerie, and his hyperbaric chamber conspire to make him a national joke — a joke repeated each time another line of irrelevant Michael Jackson merchandise hits the stores. In record time, he has gone from being one of the most admired of celebrities to one of the most absurd. And the pressure to restore himself in the public eye is paralyzing him.

“He’s afraid to finish the record,” says an associate of Jackson’s. “The closer he gets to completing it, the more terrified he becomes of that confrontation with the public. Quincy Jones could only keep him protected from it for so long, then he leaves the studio and it’s there. He’s reminded that everyone is waiting for this record and he goes into a shell. He is frightened.”

The first thing that people who know him tell you is that there is Michael and there is the corporate entity called “Michael Jackson.” “He has a split personality,” says a member of his staff. “He is very bright and self-destructively brilliant. He has an extremely high I.Q. and certain quirks and personality disorders. He might have six or twenty sides to him, and they’re all competing against each other.”

Over the past year, Quincy Jones has devoted himself to saving Michael from Michael Jackson. Since last fall, however, Jones has been losing the battle. Michael Jackson makes more and more deals — movies, commercials, soft drinks, clothing, toys, perfumes. All of this distracts him from making the album; at the same time, all of it depends on the record’s completion. Finding a way through this impasse to make an album that could possibly follow Thriller is the most difficult challenge that Michael has ever faced.

It’s a clear, sunny day in West Hollywood. To the north, the Hollywood hills rise majestically over the splashy billboards, palm trees, car washes, burger stands, and mini-markets that dominate this seedy district. At night the area turns into a pick-up strip for male hookers and transvestites; otherwise no one goes there. It’s the perfect spot for someone who craves anonymity.

Westlake Studio is a well-kept secret, a nondescript, two-story red brick building with beige trim and draped, tinted windows. No signs announce its location; it blends perfectly with the neighborhood’s bland architecture. But in the tight alley behind Westlake sit Mercedes, Rolls-Royces, Ferraris, and stretch limousines with judiciously darkened windows.

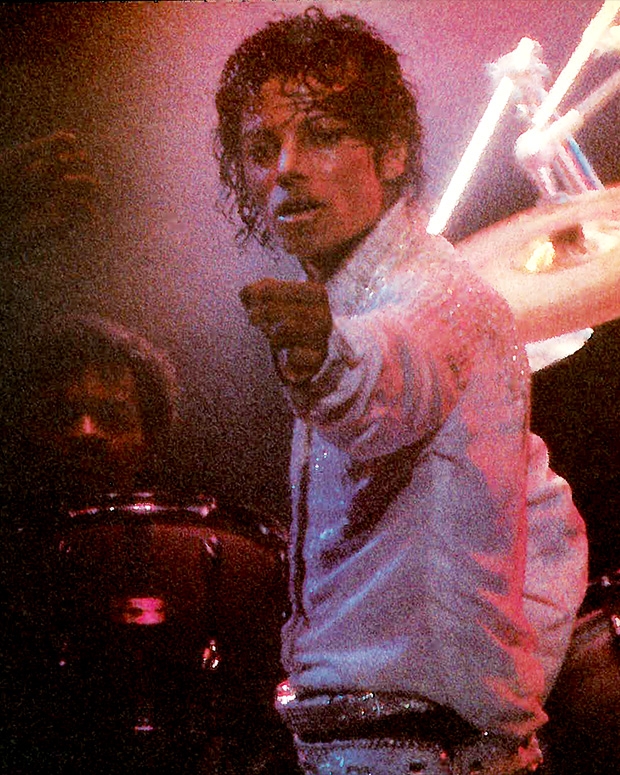

Inside the studio, Michael Jackson is pacing the floor as jazz organist Jimmy Smith lays down tracks for a song called “Bad.” It’s a leaping, driving, swaggering song about what a young man can do in bed, seemingly made to order for Smith’s hard-swinging style. He has knocked out one remarkable take after another, improvising solos with a wide, toothy smile.

But Michael wants something more. After the playback, he hears Lola Smith ask if everyone picked up on Jimmy’s grunts while he was playing. Now Michael wants those grunts on tape, says he has to have them. Smith goes back into the booth to deliver again, this time complete with funky grunts. During these takes, Michael comes out of his shell, rocking and stamping his feet. He doesn’t ever talk much, except to Jones and Frank DiLeo, his short, squat manager who has just come into the studio wrapped in a billowing cloud of cigar smoke.

As Michael nibbles on a pomegranate and whispers in DiLeo’s ear, Smith begins another solo, this one even more astonishing than the others. He finishes the take and returns to the booth, sweating and staggering like a man who has been drinking and screwing all night. Michael embraces him warmly.

This is the Michael who is a pleasure to work with, a gifted songwriter and prankster. Quincy Jones watches him with obvious satisfaction. The troubles of last year seem behind them. The many Michaels have been distilled into one and he’s in the studio working well.

Things aren’t always this easy. Taciturn himself, Michael demands constant stimulation. He is childish but domineering, shrewd yet abstracted. He is rich and powerful, but also an insecure child. He can be angelically sweet or cuttingly cold. His every whim is satisfied. He gets what he wants, but only as long as he remains inside the cocoon of his self-created isolation.

The intimation that he’s withholding something is vital to Michael’s mystery, what makes him a star. And his sedulous commitment to the Jehovah’s Witnesses is his most elusive secret. What others suspect to be some dark, subterranean sexuality may in fact be just the opposite: a reflection of the Witnesses’ severe prohibitions against sex and sexual fantasy. Stories proliferate that he won’t even allow sexual banter in his presence. People who work with him just have to learn to live with this.

Sometimes the strain even gets to Michael. Jehovah’s Witness tenets include belief in an apocalypse that only Witnesses will survive, stern sanctions against premarital sex and homosexuality, and warnings against contact with the secular world. Michael rebelled through his music, especially on Thriller, which was about much that the Witnesses disdain — teenage sex, one-night stands, unwed mothers, gangs, vampires. It was only a symbolic revolt, but it was a potent one, touching millions of lives.

It sent shock waves through the Witnesses. At the Kingdom Hall, which Michael attends in Encino, there was a division between his young Witness fans and the grim-faced elders, who had already issued veiled warnings about his success, pointedly preaching against the sin of pride. The “Thriller” video, with its suggestions of vampirism and strange sexual rites, brought it all out into the open. Soon there were private meetings between Michael and the elders, discussions about the state of his soul and the damaging effects of his video.

As “Thriller” went into heavy rotation on MTV, Jehovah’s Witness headquarters in New York released an official statement condemning it. In L.A., Michael was called into still more meetings with the religion’s leadership. Shortly after one of those meetings, he issued his own statement repudiating the video, promising never to present such images and ideas again. The public embarrassment left him shaken.

There were also problems at home, centering on family patriarch Joe Jackson, and intensifying with Michael’s success. Michael first broke with his father in 1981, after the last of their management contracts expired. As Michael’s solo career took off, bad feelings grew among his brothers, stimulated by his father’s machinations. One by one, each of the Jackson brothers produced solo records, and one by one, each was a failure. Then, in 1979, Michael released Off the Wall, which sold a staggering 7 million copies. Afterward, some of the Jacksons stopped speaking to one another, and blamed Michael for the group’s failure.

When Joe Jackson reappeared in his son’s life after Thriller, it sparked an intense struggle over Michael between Joe and an opportunistic assembly of producers, promoters, hustlers, and freshly minted friends. Playing on Michael’s fears that he had betrayed and abandoned his brothers, Joe worked his way at least partially back into favor with his famous son. Soon he was reportedly making deals again in Michael’s name. He joined with one Hollywood producer to develop a film based on “Beat It,” to star Michael himself. Michael knew nothing about it and eventually disavowed any connection to it.

But none of the projects tagged to Michael’s increasingly valuable name was as big as the one that boxing promoter Don King dreamed up: a Jackson 5 reunion tour. King bypassed Michael and went directly to his parents, offering Joe and his wife, Katherine, millions to be his partners on the tour. While King worked on Joe Jackson, Jackson worked on Michael. Michael’s plans called for a major tour of his own to support Thriller, as well as various film projects, but the pressure from his father and his brothers finally became too great and he bowed to their wishes. The tour and the album that would be whipped up to justify its existence were titled “Victory.”

It was a disaster. Michael was hospitalized when his hair caught fire during the filming of a commercial for the tour’s sponsor, Pepsi; threats of boycotts from black community groups incensed by exorbitant ticket prices dogged the tour; King was reduced to a figurehead and replaced by New England Patriots owner Chuck Sullivan, who lost millions on the tour and subsequently sold his stadium to cover his losses.

Although Michael tried to present a harmonious public image of his family, it was impossible to disguise the simmering jealousies. Now, his obligations fulfilled, he wanted out. “It was devastating,” says Joyce McCrae, a longtime Jackson family employee. “This was the culmination of the least wonderful experience that he has ever had with his family. Michael’s tremendous success has affected every member of his family. Some are jealous, there’s been denial, there’s been the whole gamut of human emotions. Jackie’s the most bitter, the most hurt by Michael’s success, because he thinks he put Michael out front in the first place. He’s also the oldest. There’s this assumption that he created Michael.”

Michael Jackson steps into the quiet studio in West Hollywood dressed in a red corduroy shirt, black corduroy pants, a brown belt with a gold eagle buckle, white sweat socks, and black espadrilles. He has on ’50s-style dark shades, a brown fedora, and his long jeri-curled hair is pulled back and tied into a ponytail. A chimpanzee dressed in overalls sits on his shoulder one minute, in his lap the next.

At one end of the studio, a spread of fried chicken, potato salad, greens, and cole slaw has been arranged. The key men are present: Quincy Jones, who is sitting on the floor, making notes between spoonfuls of soul food; Bruce, the walrus-mustached engineer; and Frank DiLeo, who sits back in the control room sending long streams of cigar smoke curling toward the ceiling. They’re taking a break before Run-DMC come in to collaborate on an anti-crack song. Michael sits on a piano stool and says little.

At 29, Michael Jackson looks barely 19: in his white pancake makeup, he looks like a ghost. Assimilation has traditionally been a social phenomenon — blacks, Hispanics, and Asians moving into white society as they prospered — but Jackson redefines it. Through cosmetics and plastic surgery, he has assimilated himself biologically, recreating himself in a Caucasian image.

Run-DMC come swaggering into the studio dressed all in black — black hats, black shirts, black pants — except for their white Adidas and inch-thick gold braids hanging around their necks. “Yo, what up, Q?” they shout to Quincy as they invade the room.

Jones embraces them and introduces Michael. They seem taken aback by his shy, quiet presence, as if they thought the real Michael Jackson would be different. Seconds tick by, punctuated by silence. The rappers turn away at last and start jiving noisily with each other. And Michael drifts through his own calm, through some serene place where he lives most of the time.

The meeting unsettles Run-DMC They can’t seem to get on track with the anti-crack rap — something, according to Jones, is missing from their lyrics. He tells them to try to rap with more sophistication — metaphorically, symbolically. They work on it again but can’t get anything together before they have to leave. Michael puts on his headphones and slips quietly into the recording booth’s single spotlight. He will be here until it all comes together.

Even in exile, Michael found no peace. “The media attacks surfaced again,” says Joyce McCrae. “So he isolated himself even more for protection, and put himself in the company of people like Elizabeth Taylor and others who accepted him as he was, because they too have been attacked by the media and understood what he was going through. Michael’s obviously found ways to deal with the pain caused by the media, but he has spent a lot of time just hurting. You build a wall around yourself and try to do things to make yourself immune to pain without losing your humanness. That’s the hard part, staying human.”

Many of the attacks came from white rock critics who suddenly seemed to resent his unparalleled success. Jackson doesn’t fit the model for rock critic idolatry. Someone like Bruce Springsteen plays the guitar, writes songs that are subject to literary criticism, and dances like a white guy. Whereas Michael Jackson represents a black cultural heritage that white rock critics either don’t know about or would rather appreciate nostalgically from someone who’s dead.

More and more, Michael cloistered himself in his mansion in Encino, California. The estate sits behind a large wall with a huge black iron gate, which is heavily guarded at all times. The only thing the fans who gather around it ever see are the darkened windows of stretch limousines as they burst from behind the gate.

Inside the estate, Michael fashioned his own fantasy world, inspired by the imagination of Walt Disney. “I went to see him about some music,” said one songwriter, “and while I was sitting in the living room waiting for him, I had this sensation that he was in the room somewhere, watching me. Then he came in, we talked, and he just disappeared. I looked out in the yard and he was darting in and out among these bushes and trees, chasing these little animals. He was like one of them.”

It’s possible that his retreat into a childlike world saved his life. “You have to understand that he has been mobbed,” says McCrae. “He’s been pulled at, had his jacket ripped off his back, had people trying to get a lock of his hair. Do you know how frightening it is to have someone coming at you, grabbing at your throat?”

“He’s not really happy,” says Dennis Hunt, music critic for the Los Angeles Times, who’s known Michael for many years. “He’s been affected by the pressures of not having any privacy. And people who know him well say it’s finally gotten to him, and he’s staying away from people. He’s not dealing with the pressures the way he used to. There’s no way that he will turn outward and live in the real world again. People thought that at some point he might outgrow it and open up, but now that’s impossible. Because of the level of stardom that he has achieved, he is alone most of the time, except for dealing with members of his family, a few friends, and his menagerie of animals.”

But if Michael’s exile appeared to be a retreat from the world, it was nevertheless a handy cover for his next moves. Last March he launched a long, complex campaign to buy the 4,000-song ATV Music publishing catalog, which contained all of the Beatles’ songs. With a team of lawyers, he executed a brilliant end-run around his friend and associate Paul McCartney, who was also bidding on the catalog, and paid $47.5 million to close the deal. It was a coup, but it strained his relationship with McCartney.

His relationship with Diana Ross had long been on the wane, suggesting he had finally broken free of the strong influence she had held over him since the early Motown days, when she moved him away from his family and into her home. “She was Motown’s superstar and she was at the level that Michael strove to attain,” says McCrae. “Diana was certainly his first-line impression of celebrity. He liked the way she carried herself, her style, and tried to emulate her. I think that Michael’s changed his opinion about all of that, about Diana, since he has been hanging around with Elizabeth Taylor, Jane Fonda, Sophia Loren, Liza Minnelli, and Katharine Hepburn.” Last summer, when Ross married a Norwegian financier, Michael declined to attend the wedding.

Holed up in the house in Encino, estranged from much of his family, Michael again began to focus on the sequel to Thriller, but he found himself plagued with self-doubt. It was the time of Prince’s purple reign, and a new erotic symbol had captured the popular imagination, one as mysterious but far more visible than Michael.

Early in 1986, Quincy Jones arranged a meeting in Los Angeles between Michael and Prince. According to one observer, it was a strange summit. “They’re so competitive with each other that neither would give anything up. They kind of sat there, checking each other out, but said very little. It was a fascinating stalemate between two very powerful dudes.”

After the meeting, Jackson got serious about the album. By late spring, he was feverishly writing songs. Quincy Jones was also gearing up for the record, scoring arrangements, hiring musicians, and mapping out ideas. In March of 1986, he went to New York to scout black rappers. “He and Miles Davis are the only musicians of their generation who in any way have connections to the younger generations,” says writer and Michael Jackson biographer Nelson George. A lot of Jones’s time was also spent with Michael in a kind of therapy, trying to lift from his shoulders the strain of having to reproduce the innovative spark of Thriller. It was a problem, Jones would soon discover, that could not be solved.

“Michael Jackson is not an experimenter,” George continues. “He generates some songs, but he’s not a creative artist like Prince. He’s more Cab Calloway than he is Duke Ellington. He’s also very comfortable with The Sound of Music and that whole Broadway-Hollywood white thing. I mean, he’s kind of Bing Crosby updated. Except for a few songs, like ‘Billie Jean,’ ‘You Wanna Be Startin’ Something?’ and ‘You Push Me Away,’ his songwriting is not rich.”

It is Quincy Jones’s job to make it rich. Many think Michael couldn’t have succeeded as he has without Jones’s touch. In June, the strain of working on the record immediately after producing the film The Color Purple got to Quincy. He was exhausted; his doctors ordered him to stop work. He took off to Tahiti, leaving the album in a state of limbo.

By the time he returned in July, there were new problems. Michael suddenly broke off work on the record to star in Captain “EO,“ a $20 million sci-fi adventure film that Francis Coppola was directing for Disneyland.

In New York, CBS Records president Walter Yetnikoff was furious. The label’s profits had fallen off since Thriller, and it was counting on the record to come out in January 1987. When he discovered that Michael had written songs for the film, Yetnikoff reportedly threatened to sue him. They eventually reached a compromise: no songs from Captain “EO” would be released, and Michael would soon resume work on the album.

Michael returned to the studio in the fall. By late October, Jackson and Jones had finished several songs, including “Bad,” which was not the album’s title track. Martin Scorsese agreed to direct the video and hired novelist Richard Price to write a 10-minute screenplay about a private school kid who gets killed in a Harlem stickup. In November, Michael and his staff flew to New York for the shoot.

From the start, there were problems on the set. Tempers flared on both sides when Michael started telling Scorsese how to direct the video. Peace was finally restored, but the production flew out of financial control, with costs rising to more than $1.5 million.

January came and went without a finished album. Even optimists gave up hope that there would be a Michael Jackson record before summer.

In March, Michael dropped the project again and, unbeknownst to CBS, began to work on a new movie, one that was shrouded in extraordinary secrecy. Visitors to the set were required to agree in writing not to reveal anything they saw; staff were subjected to similarly tight regulations to prevent news of the film from leaking. At Westlake, Jones carried on without him.

But all of these delays were beginning to hurt Michael. His boldly conceived merchandising enterprises were already in motion; without a record to reassert his myth, they made no sense. His “Magic Beat” perfume failed miserably last fall. Michael Jackson clothing and doll lines, financed to the tune of $20 million, also fizzled. Pepsi, which had planned to blitz the 1987 Grammy Awards with Michael Jackson commercials, as it had done in previous years, canceled its campaign. As part of its $10 million deal with Jackson, the company already owns one of the singles from the still-unfinished album.

It’s March 1987, and it’s getting late. Westlake Studio is deserted except for Michael, Quincy, Bubbles the chimpanzee, and a few technicians. “Smelly,” as Jones calls Michael (possibly because the singer is so obsessively clean), still wants to lay down more vocal tracks. On the recording console in front of Quincy sits a comic strip clipped from a newspaper, the punch line to which reads: “Michael Jackson is 30 years old and he’s never had a date.” Michael picks it up and reads it. Then he puts it back gently and turns away. He seems hurt by the words. Half a beat passes, then he giggles like a schoolboy, and walks into the recording booth.

Alone in the semidarkness, illuminated softly by a single spotlight, he starts to sing. This, finally, is what it’s all about. Somewhere out there Prince has finished his new record and Run-DMC are thinking about theirs and Walter Yetnikoff is learning to live with the CBS balance sheets. But that’s some other place. Here, for now, none of that exists; there are no problems, no merchandise deals, no deadlines, no family rivalries. It’s just Michael and the song.

Suddenly, he is no longer the dreamy, whispering recluse. He is no longer soft. He attacks the song, dancing, waving his hands, moving with unexpected power. He is in his own world, but for once, it’s a world that others beside himself can believe in. For these few moments, at least, he is neither a joke nor an icon, just a very, very talented singer.

But then the song is over. Quincy looks on approvingly: it’s a take. Michael walks over to the console and gives him a hug. Then he pulls a surgical mask from his pocket, slips it over his head, and takes off into the L.A. night.