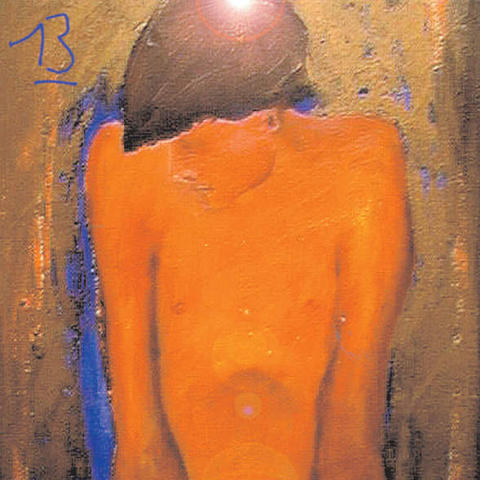

Blur‘s 13 was released March 15, 1999. In honor of its 20th anniversary, we’ve digitized and republished our original review, which ran in the May 1999 issue of Spin.

Who are Blur? Strip away the Britpop—the kaleidoscope of homages, sociological commentary, music-hall glitz, cheeky flag-waving under perpetually cloudy skies—and what’s left? Archetypically English in their determination to ignore their own should while grousing about everyone else’s shallowness, Blur have always contented themselves with surface: flirting with any genre that catches their fancy (say, American lo-fi), striking a knowing pop pose, then buggering off to find the next quick buzz. And because they’re cute, smart, prolific, and deliver a jolly good time despite the bitterness below the surface, Blur carry on while most of their Britpop peers trudge into self-parody. Too undisciplined to consummate a defining achievement on the level of Pulp‘s “Common People” or Oasis‘s “Wonderwall,” these well-bred bohemians have instead turned their restlessness into an asset. For better or for worse (mostly the latter), you know what those other lads are gonna do next. With Blur, the future’s still up for grabs.

Their sixth proper album, 13, opens on a topic Blur have studiously avoided for the last eight years—love and its loss. “Come on, come on, come on / Get through it / Love’s the greatest thing / I’m waiting for that feeling to come,” Damon Albarn sings on “Tender,” with a sincerity that would have once seemed ghastly, but now jibes with Britain’s new school of indie acoustic. You’ve heard this sort of forlorn country-would and gospel yearning from Spiritualized, Beth Orton, Belle & Sebastian, and the Beta Band. Yet “Tender” is more than a bid for continued cred: This is the “I Want to Know What Love Is” of the ’90s—a quiet implosion of anguish and hope that transcends Britpop cliché the same way Foreigner’s sole moment of greatness soared above crap FM rock. here’s the emotional clarity that’s been cloaked in sharp sporting gear. But it’s come at a cost: Albarn lost the love of his adult life, Elastica’s Justine Frischmann, and the void speaks louder than wit.

The album’s lead single, “Tender,” misrepresents 13 just as “Song 2″‘s grunge metal parody baited-and-switched American alternateness on Blur’s previous go-round. It’s simple, clean, and accessible, while most of 13‘s other tracks are complex, murky, and abstract. It beckons you into warm amniotic fluid, buzzes, roars, testifies, and gets seasick, managing to sound simultaneously like a party and its hung-over aftermath in the bathroom mirror. So long Ecstasy, sugar high, lager, lager, lager—say hello to squishy, squirmy, self-revealing psycho-delia.

But Blur haven’t abandoned the consolidation of their beloved record collection. Trainspotters will detect Bowie, the Fall, Wire, Nick Drake, Butthole Surfers, Syd Barrett, and a heaping helping of Amon Düül II; the rest of us will hear a screwy record as toothsomely difficult as guitarist Graham Coxon’s solo spew last year was a piece of dog doo. Yet while 13 opens hungering for happiness and ends waving Frischmann good-bye while fighting to remain dry-eyed, it is no ordinary confessional. Despite Albarn’s newfound urgency, poetic abstraction and vocal distortion obscure the specifics of his heartbreak, leaving you to feel him missing his kissing without knowing precisely what he’s going on about.

After sculpting the user-friendly technopop of Madonna‘s Ray of Light, producer William Orbit lets his freak flag fly here. This is electronica the old-fashioned, pre-digital, Krautrock way: Guitars scrape and scream, ancient synths bubble and belch, the rhythm section grooves as if beaming in from a distant planet. Venturing even further into alienated hyperspace than Radiohead‘s influential OK Computer, 13 similarly applies dance music’s aural fixation to dirty guitar drones, warping and layering crudeness until it’s vastly complicated. Albarn and Coxon try to maintain decorum through the heartbreak on the album’s most straightforward song, “Coffee & T.V.,” but Coxon lets loose a series of distort-o-riffic solos that scream nervous breakdown. He’s evolved into quite the ax-grinder: Check the six-string abuse on “Bugman,” “Swamp Song,” and “1992” for further proof he can kick most of our Nerf-grunge Yankee asses, even with an electro-disco producer in the studio.

After the toy-hardcore temper tantrum of “B.L.U.R.E.M.I.,” it’s hard to tell where one gritty head-trip ends and the next begins, and chorus-shunning titles such as “Battle,” “Mellow Song,” “Trailerpark,” “Caramel,” and “Trimm Trabb” are no help. Rather than assuming characters in the songs, Albarn drifts with the wasted vibe, lost in music, caught in a trap, no turning back. Discordant chords drop out of nowhere, lurid guitars fade away only to return churning, the bass goes dub-dub-dub, and conventional song structure surrenders to entropy and perverse editing. It’s a mess, and so are Blur, bless ’em.

That’s why—in the grand post-relationship-record tradition—it all works. 13 is one long, petulant bender. Yet it also suggests that scary word: maturity. There’s a sense of experience and exhaustion in its experimentation that makes the album as world-weary as it is otherworldly. Blur the band is ten years old, its members now into their fourth decades, and, although at last report the once-hard-drinking Coxon may have fallen off the wagon, sobriety informs the crazy dusted drama. Coming off a U.S. breakthrough that stooped to conquer the Ameri-phobia of this shamelessly Anglo act, 13 could have slinked into sellout mode. Instead it contemplates growing weirder while growing older, and although it doesn’t make peace with that possibility, it goes barmy anyway because weirdness is vital and real. Imagine Oasis taking that same leap.