Pop music, at least its apex, is the province of the audacious, from Elvis twisting his hips, to Prince, Madonna, and Janet Jackson rearranging sexual norms, to Missy Elliott writing hooks consisting of gibberish and backwards vocals. The best pop stars do things we don’t expect because they are also things we can’t conceive. In this grand lineage, I submit a Drake album featuring a song titled “Madiba Riddim.”

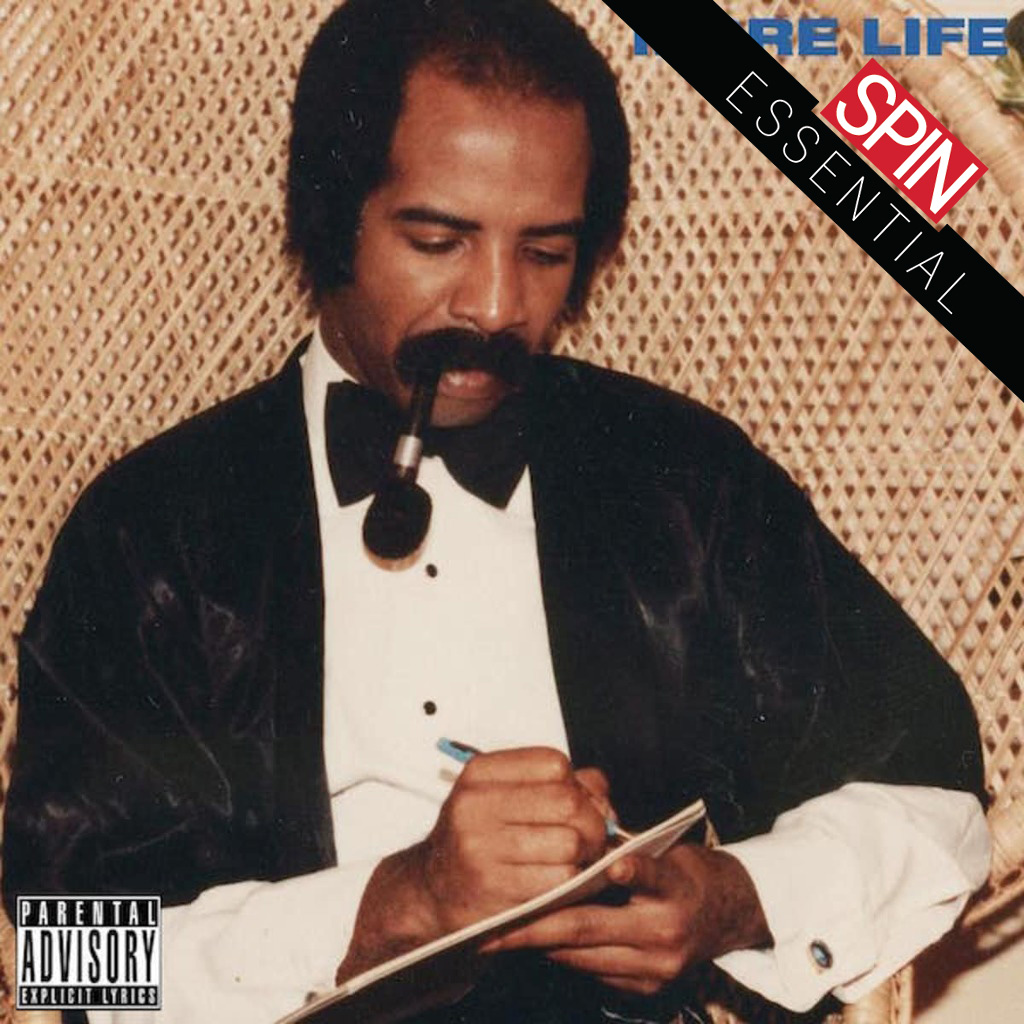

I’m kind of kidding, but as Drake continues to cement himself as a generational star, it’s worth taking stock of the exact nature of his audacity as a pop musician, the divisiveness of which seems to track exponentially alongside his commercial success. That audacity, of course, is his abandonment of the American rap/R&B binary and embrace of the pan-global sounds of the black diaspora: grime, afrobeats, dancehall, and house music, at least so far. This voyage was charted in earnest on last year’s Views, which sported only three hits—“One Dance,” “Controlla,” and “Too Good”—that were each tethered to dancehall. In the case of “One Dance,” it was mostly a spiritual connection, but it was more direct with the other two, which respectively sported snippets of vocals from Beenie Man and Popcaan to go along with obvious aesthetic inspirations. On More Life, his new 22-track… whatever, Drake uses those three records as a launching point for a far superior follow-up that stands as the opus of the second phase of his career.

The divisiveness of Drake’s evolving discography stems from a question that may provide enough debate fodder for decades to come: Is he more omnivore or carnivore? Is he sampling the sounds of the world and returning to those that he likes best, or is he hunting prey and picking their bones clean? This question is complicated and speaks deeply to our times, hitting themes of appropriation, gentrification, and identity. It’s also a specific moral question within the strict context of the music industry, one which is impossible for outsiders to answer, though Drake has not yet been accused of pillaging by his collaborators or sample sources. Instead, the argument against Drake is the opposite—that he’s too close to the cultures that inspire him, a smothering and clownish presence who is less his own man and more of an actor playing dress-up with slang.

If all of that can be put aside, the question is also an artistic one. Is Drake good at it? Does his tourism actually result in music you want to listen to? This question is as divisive if not more than the other one, but More Life makes a strong argument for Drake being the best sort of pop star, one who uses his power as an incredibly famous musician to synthesize and codify the vast world around him into a consumable and replayable product that brings people together and pushes them apart in equal measures.

Also Read

KEEPING IT REAL — ROUND TWO!

To that end, “One Dance,” his greatest success as an interloper, is undersold as an artistic achievement. Looped in with the others as Drake’s idea of dancehall karaoke, it was actually a canny display of his unique ability to construct his own little world out of a constellation of influences. The song does indeed sound like dancehall—and Drake does affect patois—but its source DNA comes from elsewhere: Paleface and Kyla’s “Do You Mind,” which was popularized as a remix by the DJ collective Crazy Cousinz. That group was at the forefront of a fleeting but highly rewarding underground subgenre of British dance music called funky house, which blended traditional house with polyrhythms influenced by the percussion of Africa. Also featured on “One Dance” was Wizkid, made to sound like a dancehall vocalist as well, who is one of the faces of the Nigerian genre afrobeats, which, by remaking African music in the image of Western pop music, sort of does the reverse transaction of funky house. Drake consumed all of this and spit out his own sub-three minute pop number one, which was a far more entertaining and catchy vessel for the wonderment of pop music than, say, this paragraph.

The best of More Life expands on that endeavor. “Get It Together” is a re-write of sorts of the South African producer Black Coffee’s deep house track “Superman” that Drake almost completely relinquishes to the British singer Jorja Smith, who turns in a smoky and soulful vocal performance, not replicating Drake’s duets with Rihanna but expanding on them. “Madiba Riddim”—which, c’mon, sounds like a 30 Rock joke about Drake—is a soothing hit of afropop built, presumably, around shards of guitar from the Canadian artist Frank Dukes. “Blem”—island slang for high—is another Drake reimagining of dancehall that winks at you with brief interpolations of Lionel Richie’s cruise ship classic “All Night Long.” “Passionfruit,” a possible people’s champ of a single choice, asks the grime producer Nana Rogues for his version of “Hold On I’m Going Home,” its emotional resonance coming appropriately, though subtly, from its percussion. “Ice Melts” doesn’t quite find the place where reggae meets Pimp C’s country-rap funk, but it’s a valiant attempt that nonetheless inspires an emotive Young Thug.

With these sorts of songs, Drake isn’t just completing elaborate math equations. He’s funneling the Earth through his own established aesthetic, making songs that throb with longing out of music that usually bangs. More Life succeeds where Views failed because this thread connects to the album’s more typical rap music, too. “Portland” is a muted, atmospheric take on rap’s burgeoning obsession with flute loops. “Sacrifices,” the album’s most arresting track, is as lush as the intrinsically warm “Madiba Riddim,” and in turn it extracts a sage verse from 2 Chainz—“Cold world I be chillin’”—and a stunner of a feature from Young Thug, who raps in a relaxed rasp that renders him initially unrecognizable. “Glow,” as close to anthemic as this album gets, peels away Kanye’s celebratory Graduation until it’s a just a strip of LED lights flickering in the dark.

Though Drake’s globetrotting is seeping into American pop (hi, Katy) More Life still stands apart. Its closest recent antecedent is probably Drake’s own Take Care, itself a kaleidoscopic masterpiece that pulled horizontally and vertically from across music. More Life also feels like an apology for Views, an alienating and bloated record that had a good album hidden inside if you were willing to take a machete to it. At the end of this one’s sneering “Can’t Have Everything,” Drake plays an old voicemail from his mom, who says, “Hun, I’m concerned about this negative tone that I’m hearing in your voice these days.” On the closer “Do Not Disturb,” he issues a full mea culpa, rapping, “I was an angry youth when I was writing Views / Saw a side of myself that I just never knew.” More Life has its fair share of tough talk and clever shots at enemies, but it’s an altogether more centered, approachable, and enjoyable album, embodied by its optimistic and hopeful title.

That is, of course, just one man’s take, and the artistic and moral merits of More Life will be the source of fierce arguments as a generation canonizes its own pop music. To that I say—great. The ambition and aplomb of More Life is what makes pop music a thrilling cultural institution. The instinct to draw boundaries around and across pop is understandable and healthy—one rap verse from Taylor Swift was enough, as was one rock album from Lil Wayne—but Drake, love him or hate him, is a reminder that we’re better off letting our pop stars run wild, just in case they return with something this good.