Back in January, an anonymous Discogs buyer apparently shelled out $18,000 for a copy of a rare rock album called 301 Jackson St, the highest-ever recorded sale on the online hub for record collectors. The 301 Jackson St. sleeve appears battered and scuffed in a photo, and the seller described the condition of the album itself as “poor.” “It is worn, what would you expect ( read the stories),” he or she wrote, somewhat cryptically, alongside the listing. “The record itself however plays beautiful. You can’t find one anywhere.”

Such extravagant sums aren’t out of the ordinary in the rarefied realms of early-century country blues 78s and historically significant Beatles artifacts, but this album was different. 301 Jackson St. was recorded in 1989 by a guitarist named Billy Yeager, who has no Wikipedia page, and whose name would be difficult to place for even the most devoted record collector. “Billy is somewhat of an enigma…” wrote Jeffrey Smith, who handles publicity for Discogs, in an email touting the record-breaking sale to journalists on Monday. “A guitarist from Miami that some have called a guitar god!” Outlets including SF Weekly and Stereogum responded with blog posts. “Who the fuck is Billy Yeager anyways?,” the SF Weekly writer wondered.

After multiple inquiries from SPIN about the nature of the sale, Smith said Wednesday evening that a subsequent internal Discogs investigation had found the transaction to be fraudulent. At around the same time, pages documenting the sale were removed from the site, and on Thursday morning, Discogs sent a second press release to journalists to explain the error. “Discogs’ priority will always be preserving the integrity of our user-built database,” Discogs CEO Kevin Lewandowski said in the release. “With hundreds of thousands of contributors, buyers, and sellers, putting their trust in our community, Discogs’ mission will continue to be built on the love of music, not the duplicitous nature of the hustle.”

The most expensive record ever sold on Discogs was a hoax, but what’s not exactly clear is who orchestrated it. In earlier conversations, when Discogs remained somewhat confident that the 301 Jackson St. sale had been legitimate, Smith explained the company’s process of verifying the transaction “We’ve had a seller sell a record to a buyer,” he said. “Both are different accounts in different parts of the United States, and the transaction came through.” The seller had paid Discogs the standard transaction fee, which is typically eight percent of a an album’s selling price, but is capped at $150, he added. “After that, it’s not our responsibility to verify that it’s real people, or if the seller is somehow affiliated with the buyer. We’re a C2C company. The transaction happened. That’s the end of our relationship, as long as the buyer and seller are happy.”

Who would set up multiple dummy Discogs account and shell out 150 bucks, just to make it seem to the world that a record by a little-known guitarist named Billy Yeager was commanding higher prices than rare recordings by David Bowie and Prince? And why?

Billy Yeager’s story has all the makings of record collector catnip, starting with the apparent rarity of his releases. Only eight test pressing copies of 301 Jackson St. exist at all, according to the Discogs listing for the album, and other recordings aren’t any easier to find. A seven-inch called Jimmy Story, for instance, is listed for $25,000 on the website of Surf Jazz Records, a label that seems to exist solely to sell Yeager’s music. If you want to hear him play and don’t have the many thousands of dollars for which each of his releases is listed for sale on Discogs and the Surf Jazz website, you’ll have to settle for one of two blown-out VHS clips on YouTube, the only bits of Yeager’s music available for free streaming online. The first is from the early ‘80s, showing the guitarist dressed like a South Florida version of the Thin White Duke, throwing down a solo during what might be some sort of televised performance. In the second, he’s wearing a tank top at a backyard party a decade later, shredding and playing chicken-scratch funk chords, backed by two dudes with mullets and another in aviator sunglasses. This second video is advertised as a preview of “Billy Yeager rare footage for sale,” and its description makes the intriguing claim that it was recorded shortly after Yeager was “discovered” by the soft rock hitmaker Bruce Hornsby. The asking price for the footage is $15,000.

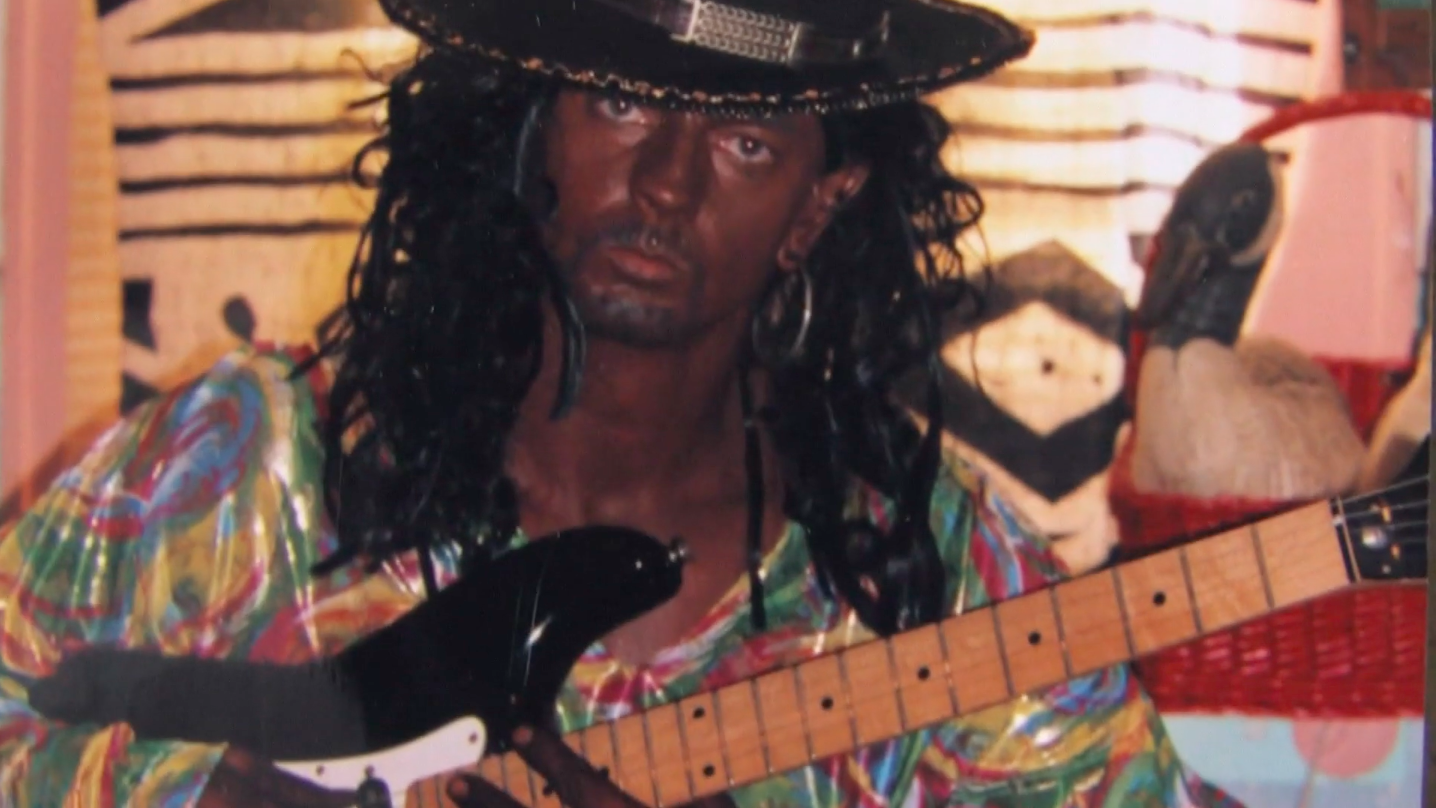

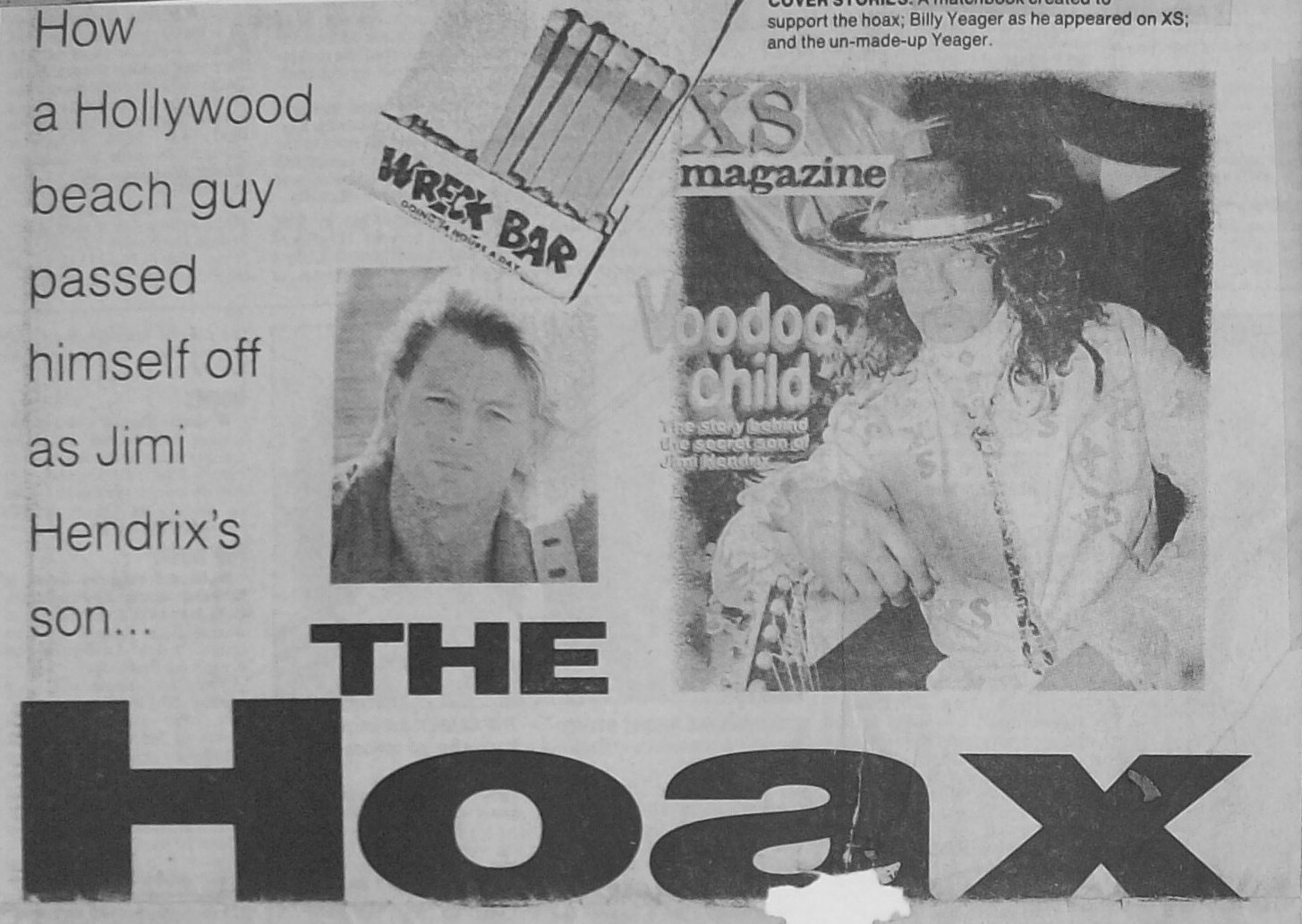

Online searches for Yeager’s name turn up pages about his music, and about his work as a documentary filmmaker. They also reveal news stories about two hoaxes he attempted to perpetrate at different points in his career. In 2011, when a grand piano found in the middle of the Biscayne Bay caused a minor local sensation in South Florida, Yeager and his wife claimed to have placed it there as part of a guerilla art project, only to be debunked when the real artist came forward. And in the ‘90s, Yeager donned blackface and told reporters he was the long-lost son of Jimi Hendrix, calling himself Jimmy Story. To prove his claim, Yeager made a batch of recordings of himself playing fuzzy blues guitar and singing in a frog-throated imitation of the late guitar god, claiming that the tapes had been passed down to Story after his father’s death. According to a Miami Herald story about Yeager from the era, his Jimmy Story costume made him look alternately like “a Diana Ross drag queen” and “something out of The X-Files,” but that didn’t stop the now-defunct Broward County alt-weekly XS from putting Jimmy Story on its cover, or the local Channel 7 nightly news from giving him credulous coverage.

“Yeager’s previous claim to fame was his notorious lack of success as a would-be pop recording star,” the Herald article reads. “Several years ago, Dade’s alternative paper New Times declared him one of South Florida’s best unrecognized musical talents. Now he’s 38. He hasn’t performed in years. He says he survives on odd jobs and lives in a cramped beach apartment with surfboards on the walls. He has a drawer jammed with hundreds of terse rejection letters from record companies.”

I started looking into Yeager after reading Stereogum’s news post about the 301 Jackson St. sale, figuring I should hip myself to this cult hero musician whose work I’d never encountered before. The first thing I found was a trailer for a film called Billy Yeager / The Ineffable Enigma, which positions him as an unsung genius, without showing any footage of him actually playing. “The greatest guitar player in the world,” reads a title card attributed to the virtuoso bassist Jaco Pastorius. “The funkiest guitar player I ever heard,” reads another, attributed to Prince.

Hoping to contact Yeager, I called several numbers associated with his name in Florida public records, all of which came back disconnected. I visited his website and the site of his record label, both of which list one Chris Von Weinberg as Yeager’s press agent. Both sites carry the same warning above Von Weinberg’s email address:

Attention to the press regarding 301 Jackson St. album:We are not addressing any questions regarding the album; if you are seriously interested, watch the film documentary and then contact myself with verification that you have watched the film, and I will be willing to answer your questions.

The only way to watch Billy Yeager / The Ineffable Enigma, directed by Von Weinberg and someone named RK Devonshire, is to pay $24.95 for 24-hour rental access to a Vimeo stream. In the name of journalism, I plunked down the $25 and started watching.

The film opens with shots of Yeager playing guitar in the desert and a woman who appears to be his wife slowly dancing along. A woman’s voiceover narration makes reference to Yeager’s brushes with famous musicians, including Hornsby, Prince, Pastorius, and Rod Stewart, and to stints he spent living in his car. The film claims that he is the nephew of Bunny Yeager, a pinup photographer known for her work with Bettie Page. The editing is jerky and disorienting, and there is one scene of potentially alarming violence. Vintage-looking VHS footage shows a man who appears to be Yeager dressing up as a police officer, strip searching a black man, taking money from him, and leaving him naked and handcuffed to a fence. Another sequence shows Yeager laughing with a friend after apparently having fooled several people into believing he’d committed suicide. The film gives no explanation for whether these sequences are real or staged.

Between shots of Yeager playing various instruments and showing off his paintings, the narrator gives a list of the artist’s baffling bonafides:

His preferred audience is nature, the ocean, and buffalo, and he only performs in the desert, and underground, in an underground missile base. He’s painted alongside some of the world’s most famous folk artists. He once dyed his skin permanently black and convinced the press he was the long lost son of Jimi Hendrix. He spent five years discovering a sacred geometric higher conscious wave frequency, and has composed music that can heal disease. And he has proposed a legislative bill that would ban the lower conscious wave frequencies in rap music from being heard in all public places. He has crossed rivers of crocodiles to perform for the wild monkeys in the jungles, climbed mountains to play his guitar in the wild. He has sunken himself underwater, trying to discover, write, compose, and record the world’s perfect song. He has produced award-winning films, but he never releases them to the public. He produces movies, but only on his own terms, and the only place to see them is on a movie screen that resides in the remote regions, somewhere in the Mojave Desert. His films, music, record albums, cassettes, VHS tapes, and CDs command the highest prices in today’s market.

The film seems dedicated to convincing you not only of Yeager’s reclusive genius, but also of the rabid collectors’ market for his releases. There are several interviews with men who appear to be collectors of Yeager albums, and shots of his records listed for exorbitant prices on eBay. One scene shows a dumpster apparently filled with Yeager releases being emptied into a trash truck, as a voiceover explains how the artist once threw away everything he ever recorded–over 1600 recordings–in frustration with the record industry’s failure to recognize him. In a scene that plays like parody of obsessive record collector culture, a Dutch-American man identified as Ton Haak stands in a room filled with brightly colored paintings and holds a CD copy of Yeager’s album The Perfect Song. “There are not many of them,” he intones lovingly. “I think maybe this is the only one.”

When I was about halfway through watching The Ineffable Enigma, I emailed Chris Von Weinberg and told him I’d like to interview Yeager about the 301 Jackson St. sale. Von Weinberg tersely explained that Yeager does not do interviews. He told me that “writers from everyone in the biz” are trying to contact him, and began quizzing me to see whether I’d actually watched the film. “So tell me, did you see the part about the science and wave vibration? Yes or No?” he asked. “Did you see the part with the red truck and sheep that were following and what the news piece said about the ‘sheep guitar truck’? Yes or No?”

Eventually, my search for Yeager led me to contact Love Garden Sounds, a record store in Lawrence, Kansas, whose Twitter account had tweeted about Yeager several times. Franklin Fantini, an employee at the store, told me that Yeager is notorious among staffers because of the calls and emails they regularly receive from people who are seeking Yeager’s records, or who want to inform the store about some new record-breaking Yeager sale. “It’s always via a different address, and it’s always via a different name. I guess I can’t prove that it’s him,” Fantini said. “He emails and says, ‘Hey, just so you know, there was this record set for this tape or record that was sold. Have you heard of this underground artist Billy Yeager?’ Well you should.”

“I’ve always emailed back and said. ‘OK, this is Billy Yeager, right, that I’m corresponding with?’” Fantini continued. “And he never he responds.”

Justin Parr, producer of a Lawrence-based podcast called A.D.D., said that after receiving several similar communications about Yeager, the podcast began to occasionally discuss his strange story on the air. Eventually, they secured an off-air interview with Yeager, after which Parr came to the same conclusion that Fantini did. “It was very difficult to get a hold of him. And in all of our contact, when we were looking into the story, all of the things that Chris Von Weinberg would say were the same things that Billy was saying,” he said. Because Yeager has showered local institutions like A.D.D. and Love Garden Sounds with attention, and screened one of his films held in a nearby theater, Parr believes that he now resides somewhere near Lawrence in Kansas.

Before Discogs recognized the 301 Jackson St. transaction as fraudulent, I asked Jeffrey Smith whether he had any reservations about publicizing a sale that looked to me like it might be a hoax. He couldn’t seem to decide whether he agreed with me that he’d been had, and spoke wistfully about the possibility that Yeager is the real deal. “This guy can shred. I’m watching these VHS tapes, and I’m like, ‘Dude is good.’ Then I went over to Spotify and there’s nothing there, and I’m like, ‘Wait a minute,’” he said.

“There’s a scene in the HBO series The Young Pope, where he’s decided he’s not going to have an image of him out in the public. He lists off Banksy, other famous authors, poets, musicians, Daft Punk—what do they all have in common? You don’t see their faces. They’re mysterious, and that’s why people value them. It’s their art, but it’s also that you don’t know anything about them,” he added. “I’m not saying that’s definitely the case here, but that would play into his appeal too. Maybe the guy’s a creative freak. Maybe he really did destroy all of his records.”

Smith told me that even after confirming internally that the Yeager sale had been faked, he could not divulge the identities of the buyer and seller, because doing so would violate the terms of Discogs’ confidentiality agreement. After speaking with Fantini and Parr, I emailed Von Weinberg and asked him straightforwardly whether I was in fact corresponding with Yeager himself, and whether he’d faked the 301 Jackson St. sale. I haven’t heard back.

Update: Chris Von Weinberg responded to my email shortly after this story went up, denying that he is Billy Yeager. “The sale of the record fraudulent or not fraudulent is not my concern, I don’t use discogs, if they determined that, I find that rather disturbing,” he wrote. “The album is well known to several music collectors, it is featured in the film. As for the question of who am I, Andy I think you and many people in the press watch way too much reality television or something, I don’t have time for these games, you can write the story or don’t write the story. Do you really think Billy Yeager has been out of the news, press, the world, for over 20 years all so he could ‘fake an album sale’?”