Hamilton Leithauser is about to enter a new phase in his life. It’s a drizzly April evening and the husband and father of two is, as of today, now closer to 40 than 30. He’s also on the cusp of his second career. For 13 years, Leithauser crooned and howled lead vocals for the Walkmen, a largely New York-based, very New York-feeling band that favored romance, atmosphere, and collared shirts. Now, nearly six months after the group unceremoniously called it quits, their singer has gone solo, and he’s playing his first one-man show on this, his 36th birthday.

In actuality, Leithauser’s “one-man show” is anything but. When he takes the stage at lower Manhattan lounge Joe’s Pub, he does so with a 14-piece backing band that features his wife, Anna Stumpf, singing backup and another old familiar — the Walkmen’s Paul Maroon — on guitar.

“I like working with people,” Leithauser says seated inside the dull, gray dressing room at Joe’s an hour or so before the Tuesday evening set begins. “That’s the ironic thing about doing a solo record right now.”

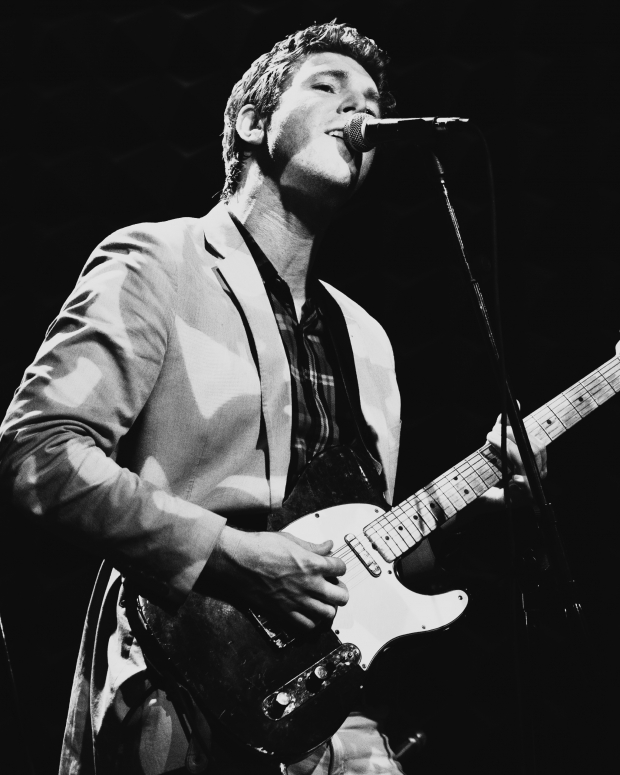

Even leaning back in a stiff chair, he appears relaxed. He’s quick to flash his strong smile, and dressed in a red flannel shirt lightly hugged by a beige suit, a casual-ish outfit that mimics his light mood. One wouldn’t expect levity from the Washington, D.C. native given his generally buttoned-up stage presence with the Walkmen. But now he seems refreshed and eager to play from his solo debut, Black Hours, an album born with the help of several collaborators, including former bandmate Maroon, Vampire Weekend’s Rostam Batmanglij, and the Shins’ Richard Swift — in other words, mostly a group of people that was not the Walkmen.

“I think that there was a lot of creativity in the Walkmen that was maybe stepping on each others’ toes,” Leithauser says of the five-piece that’s splintered into a handful of offshoot projects. Black Hours went on sale in early June, three weeks after Leithauser’s elder cousin, Walkmen bassist Walter Martin, released his own solo album, and three weeks before Walkmen organist Peter Matthew Bauer put out his first one-man endeavor. “I’m really glad that everybody can do exactly what they want,” Leithauser continues.

By 2013, the Walkmen were indie-rock elder statesmen. They didn’t flirt with mainstream success in the same way their more fashionable contemporaries did — i.e. the Strokes and Interpol — but they managed to score an enduring semi-hit with their frenzied 2004 single, “The Rat.” And like many other early-aughts acts, the band suffered a mid-decade creative slump, but while their peers floundered, the Walkmen corrected course and got better with age.

The group enjoyed a notable pop-culture cosign this past March, when the titular anthem from their sixth LP, 2012’s Heaven, soundtracked the final scene of the thick-headed but big-hearted CBS sitcom How I Met Your Mother. The series ender drew 12.9 million viewers, an all-time high for the long-running show, as well as a nice bit of exposure — and likely sizable capital gain — for the Walkmen. “That wasn’t a donation,” Leithauser says with a half-cocked smirk, after admitting he never really watched HIMYM during its nine-season run.

And yet, several months before that plum network-TV placement, Bauer revealed to the Washington Post that the band was going on “a pretty extreme hiatus.” In less than a year, the Walkmen’s seemingly permanent break has yielded a record of family-friendly yarns from Martin called We’re All Young Together, and a hazy and heavy-on-religious-imagery set of songs from Bauer, christened Liberation!

With its lush instrumentation, grand vocals, and singer-at-the-center cover image, Black Hours most openly pays homage to Frank Sinatra. Leithauser characterizes the album’s mood as “classic nightclub,” an aura that suits Joe’s Pub, a time capsule of sorts decorated as it is with cushioned booths and dark wood tabletops, dispensing potent cocktails at $15 apiece.

“I retired from my fight,” Leithauser laments onstage, a third of the way into his performance. “I retired from my war.” That doo wop-indebted track co-written with Batmanglij — and dubbed “I Retired,” of course — strolls to its end, and the man with the microphone reaches into his left jacket pocket to pull out a set list. “They can’t all be downers,” he says, sweat streaking down his still-youthful face. Then he folds the piece of paper back up, and looks out on the crowd.

“This next one’s called ‘Self Pity.'”

//www.youtube.com/embed/eTvcAm_BxQg?rel=0

Asked if he feels like he’s the same person he was 20 years ago, when he first started playing guitar, Leithauser draws a blank. “That’s a long time ago,” he says behind sunglasses one afternoon in Brooklyn’s Fort Greene Park, two weeks after his debut solo gig. “When you’re 35 and you’re thinking about your 15-year-old self, that’s tough.”

He means 36, but we’ll allow it. Trying to recall what he wanted out of music when he was younger — before his two daughters were born, before he married his high-school sweetheart, and before the Walkmen’s success — he says, “I just wanted to be in a band, a gang. My vision was never to be the solo star. In fact, I found it kind of strange and lonely to have a spotlight on me. In the Walkmen, my picture was always in the paper, my name was on the thing, but I always felt we were a gang and I liked that. I miss that, honestly.”

Leithauser followed local post-punks the Make-Up “religiously” in his D.C. youth. “But I did have a copy of In the Wee Small Hours by Frank Sinatra that my uncle left at my house,” he remembers. “For some reason I connected with it.”

He also worshipped at the altar of Fugazi, whose 1995 album, Red Medicine, features uncredited assistant-engineering work from a 16-year-old Leithauser. He’d landed a summer job at Virginia’s Inner Ear Studios through a family connection. (“I met Ian MacKaye and he said, ‘Hi, I’m Ian.’ I was just like, ‘…I know.’ I was such a geek,” he says, shaking his head.)

The gang with which he’d spend the bulk of his twenties and half of his thirties formed in 2000, in the wake of two other defunct groups. “The Recoys never went anywhere,” says Leithauser, who played in the ill-fated garage-rock outfit with Bauer. “We had zero success. Two fans. One of them was my cousin Walt.” Which, yes, is the aforementioned Walt Martin, who then played organ for Jonathan Fire*Eater. That short-lived, ramshackle quintet also featured Maroon and future Walkmen drummer Matt Barrick.

Though all five members of the Walkmen grew up in D.C., they came together in New York City, where Leithauser moved in the late ’90s to pursue a philosophy degree at New York University. “The whole thing was a waste of money,” he says of his higher education experience, now with a decade-and-a-half’s hindsight. “I guess it’s good to have a college degree for morale… But besides that? A philosophy degree isn’t going to get you a job.”

But it sort of did. By the end of his college career, Leithauser was using his time in the classroom to write the lyrics of the Walkmen’s earliest songs. A promising full-length debut, Everyone Who Pretended to Like Me Is Gone, materialized in 2002, just as a fresh class of New York rock bands revitalized the city’s music scene and spiked the currency of downtown cool.

Looking back, though, the Walkmen never made sense lumped in with ’00s aces like the Strokes, Yeah Yeah Yeahs, or Interpol. For starters, they operated out of a studio in Harlem, a 75-minute subway ride north of the nü-rock culture’s Lower East Side dominion. Their sound was never suave or particularly sexy; many of their contemporaries took inspiration and stylistic tips from the 1970s and ’80s, but the Walkmen felt truly vintage, employing upright piano for songs that appeared worn with age, and recordings that actually sounded damaged in places.

The cover of Everyone Who Pretended to Like Me Is Gone proved to be a fitting introduction: a sepia photograph of three early-20th-century newsies, young boys living hard lives, their faces engulfed in acrid smoke not unlike the steam that seemed to emanate from the songs beneath.

In 2004, the Walkmen released Bows + Arrows, their second album and defining effort. The wintry set honed the ambling, urbane discomfort that populated its predecessor and also had the benefit of hosting “The Rat,” a scorched-earth kiss-off as furious as it is weary, powered by the group’s high-speed, shimmering melodies and Leithauser’s throat-wrecking wail.

“With Bows + Arrows, I thought we were onto something and people were really responding,” the singer says. “It sort of felt like, ‘This will go somewhere.'”

But what ground the Walkmen gained on their sophomore LP was lost with their third album, 2006’s A Hundred Miles Off.

“Everybody was sort of splitting up and not putting enough time into what was finally in print,” Leithauser says, referring to a period when every member of the band moved to Philadelphia, except for him and his cousin. “Settling for something just because you don’t really want to deal with it is awful.” That same year, they released an irreverent, full-album cover of Harry Nilsson’s Pussy Cats (1974), which some considered their fourth studio LP — and second dud. A mid-career creative crisis ensued. “You think, ‘Am I just not excited about music anymore because it’s over? I’m too old, did I burn myself out? Or am I not excited because it’s not good enough?'”

Though the Walkmen did go on to have a fruitful second act, the band came to a quiet end last year. “I just don’t need to talk about it. It’s personal,” Leithauser says. “It’s not something I really want to draw attention to because it’s a band that I love with all my friends and we’re not doing it now. I don’t love that story.”

//www.youtube.com/embed/6QaFK_GvO_s?rel=0

While reminiscing about his former band’s salad days and difficulties, Leithauser gets distracted. “Oh my God,” he says, sitting with his arms folded and legs crossed on a park bench. “This is really funny — this is my daughter’s school who decided to have school in the park today.” A few hundred feet away, a dozen or so toddlers are running around a 149-foot-tall Doric column. “That’s my daughter in the pink tights,” he beams. “I didn’t realize they would be here.”

At 3 years old, Georgiana is Leithauser’s oldest. His now-wife initially broke up with him when they were teens, but the pair rekindled their romance around 2005, after she moved to New York from Minneapolis. “She came crawling back,” Leithauser says jokingly. Today, the couple owns an apartment in Clinton Hill, a small, pseudo-suburban Brooklyn neighborhood.

The Walkmen started to get slapped with the dreaded “dad-rock” label by the time they were winding down with their 2012 swan song Heaven. They embraced and even encouraged the classification by filling the album’s liners with family portraits: every member, grinning with his wife and kids. Still, responding to the idea that his old band mastered the art of growing up, Leithauser scoffs and says, “I’ll be sure to tell my wife that.”

The Walkmen’s two previous efforts — 2008’s You & Me and 2010’s Lisbon — had restored the group’s reputation. The former played like a haunted travelogue, enchanted with salted air and old-world luxury; the latter eased into brighter territory, with a breezy set of songs that carried plainspoken, heartsick lyrics with a cool self-confidence, like Ernest Hemingway set to music if you can imagine such a thing. But, as with many long-term relationships, the passion began to fade, and Heaven makes for a pleasant, if — to quote Leithauser — “flat,” listen.

Leithauser’s solo debut is far more dynamic. Originally conceived as a crooner’s record with a debt to Sinatra’s The September of My Years, his Black Hours values vocals above all else. But it does shirk its smoothness at times, as heard on the firecracker lead single “Alexandra,” another Batmanglij co-write that shares a certain explosive, shimmery charm with Vampire Weekend’s best work. Upon Rostam’s recommendation, principal recording took place at Los Angeles’ Vox Studios, where his band’s 2013 masterpiece, Modern Vampires of the City, was partially made.

“It looks like you stepped into 1922,” says Leithauser about the renowned space, which claims to be the “oldest privately run recording studio in the world” (on Facebook, at least). “When you walk into the room, it feels like Nat King Cole or Frank could be singing right in the corner.”

//www.youtube.com/embed/sVPv_lyByw8?rel=0

Though he assembled Black Hours with a group of collaborators, Leithauser says the record is his most personal to date. It’s the kind of line many musicians use in mid-promotional cycle, but it rings true for him. Two decades in, this is the first album he’s released under his own name.

And the first track he penned for the record, Leithauser reveals — before the helping hands and anachronistic scenes and looming Sinatra’s Ghost — was “I Don’t Need Anyone.” Asked what that one’s all about, he explains that it’s a love song about being “a confused, mixed-up guy, which might be the most sincere part of the whole damn thing.”

Perhaps, but after years of being one guy in a gang, Ham’s finally going it alone — or leading his own pack at least. He’s doing it his way.