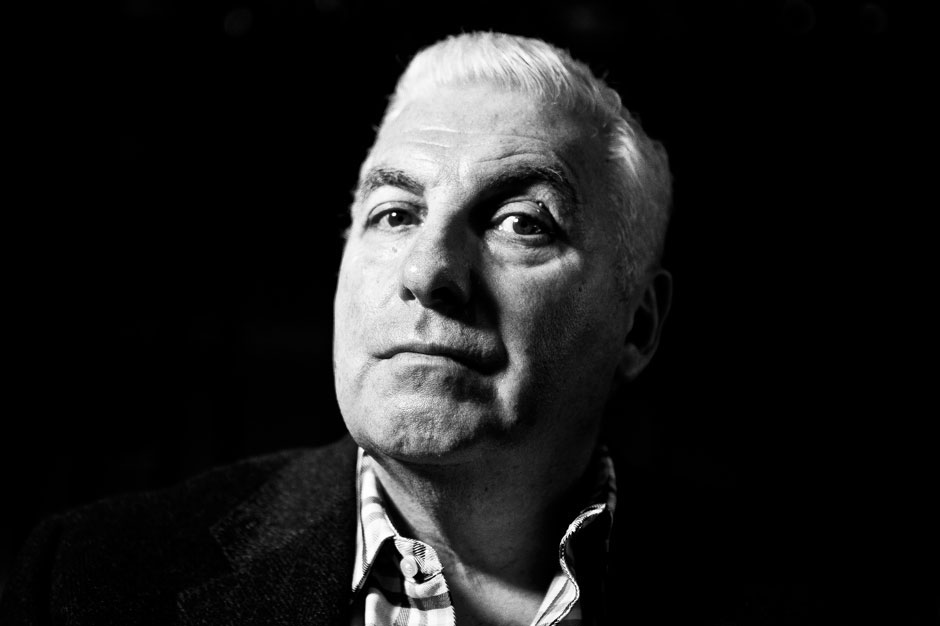

Mitch Winehouse is singing tonight because his daughter no longer can. There’s no getting around it. Sixty-two years old and handsomely gray, he’s onstage in front of a seven-piece jazz band at midtown Manhattan’s Iridium club on a mellow autumn evening, crooning and swinging through the bittersweet pages of the Great American Songbook. “But Beautiful.” “The Nearness of You.” “After You’ve Gone.”

The gig is a benefit for the Amy Winehouse Foundation, which presumably everyone in the low-lit room wishes the “Rehab” singer’s entry into the 27 Club hadn’t compelled into existence. So the tangible is here with the intangible, or however you want to describe the evening’s strange mix of curiosity, longing, and whatever other feeling can be ascribed to the fact that people have paid $25 a ticket, plus a $15 food and drink minimum, to see a semi-pro crooner with a famous last name.

Winehouse is dressed in a charcoal three-piece suit, his white dress shirt rakishly unbuttoned at the neck. There is an ease, even a suavity to his stage presence — his voice is edgeless and soft, nothing like Amy‘s vivacious purr — yet the melancholy shadow cast by the long-gone beehive renders those attributes at once admirable and vaguely unsettling. He is, and forever will be, associated with a tragedy, but right now he seems unburdened, snapping his fingers in time to the saxophonist’s curlicue solos and smiling at the happy painted ladies eating Caesar salads at tables by the stage.

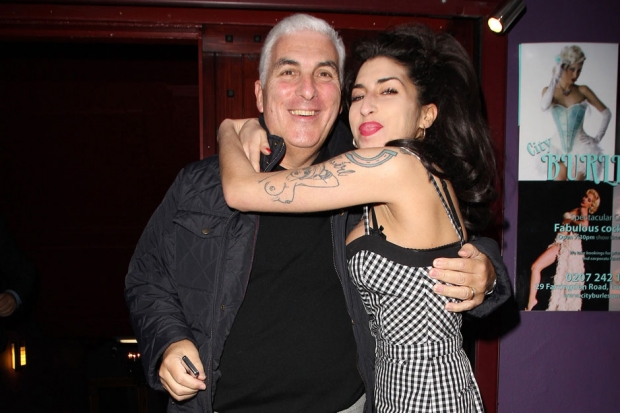

Then the mood shifts. “We do a lot of shows in the U.K. and Europe,” says Winehouse to the audience in his Cockney accent. “Sometimes it’s painful. It’s tough not having her here.” Amy is there, though, in her father’s face, in his high, round cheekbones and thick, dark eyebrows.

“The show must go on,” he says. “Amy loved this one.”

Winehouse shakes his head.

“I don’t know how I’m gonna get through this,” he says. He looks up at the ceiling. “It’s called, ‘We’ll Be Together Again.'”

It’s been two years and three months.

Mitch Winehouse’s earliest memories of singing are as a child growing up in London’s East End. His family wasn’t much for television, so parents and children and grandparents and aunts and uncles would entertain each other with songs.

“We’d all get up and do a turn,” he says. “I had an uncle playing the accordion, and another uncle played the piano. Without being professional musicians, we were quite a musical family.”

It’s two days before the Iridium show, and he’s speaking, openly and warmly, from a leather chair in the lounge of the bustling, airy Manhattan hotel at which he’s staying while in town. He’s wearing a crisp brown blazer and smells of cologne. Through his twenties, Winehouse, who even as a young man preferred Sinatra to the Beatles, started singing professionally with pick-up bands in small clubs and pubs. It was fun, and not at all lucrative or cool.

“At that time,” he remembers, “unless you were a Tom Jones type, forget it. You couldn’t make a living singing jazz in London.”

Once he got married and had children — Amy and her older brother, Alex — he gave up singing, instead paying the bills by working different jobs: sales coach, card dealer, cab driver. He has no regrets, or at least no musical ones.

“If I regret anything,” he says, “it’s that I didn’t become a soccer player. When I went to try-outs, they said I had a weight problem. I think back to what I could have done in soccer . . . In those days, Jewish guys like me were all doctors and accountants.”

I mention that there’s still not a lot of Jews in sports, and Winehouse’s eyes gleam. “You Jewish?” he asks. I am.

“Okay, I’ll tell you a Jewish joke,” he says. “It’s a bit rude as well.”

Winehouse licks his lips and leans forward in his chair. “Klein is walking through the Sinai desert, and his foot goes clink — it’s Aladdin’s lamp. He rubs Aladdin’s lamp, and a genie comes out and says, ‘Mister Klein, I’m going to give you two wishes. What is your first wish?’ Mister Klein draws a map in the sand and he says, ‘This is Israel. To the north is Jordan, over there is Syria, that’s Egypt, and that’s Saudi Arabia.’ And he tells the genie, ‘I want you to make it all Israel.’ And the genie says, ‘That’s very difficult, because you all hate each other, you have different customs, your women are different, you eat different food, you speak different languages. So Mister Klein, do you have a second wish?’ And Mr. Klein says, ‘I wish my wife would perform oral sex on me.’ And the genie says, ‘Show me that map again.'”

Microphone in hand, Winehouse let’s the raucous reverberations of the brass die down and steps to the edge of the stage.

“I was in New York when my daughter passed away,” he says solemnly. The mostly middle-aged audience’s cutlery-clinking and whispered conversations go silent.

“We went back to London straightaway,” he says. “I was in a state of shock. The first thing I thought was, Start a foundation.”

Regardless of its place in the grieving process — the first thing? Really? — the Amy Winehouse Foundation was launched on September 14, 2011, on what would have been Amy’s 28th birthday. The organization’s mission is focused on three core areas: to educate young people about, and aid those needing help with, drug and alcohol misuse; to support those at high risk of substance misuse; and to enable the personal development of disadvantaged young people through music.

Admirable stuff, but however well intentioned, charitable impulses have not always led to positive results for the celebrities (and their families) who have tried to build an altruistic legacy.

“I’ve seen a number of cases where celebrities or other prominent people have made big announcements, created foundations, and then had fairly bad results,” says Ken Stern, author of With Charity for All: Why Charities are Failing and a Better Way to Give and the former CEO of National Public Radio. “This is a fairly common problem. Notable people love the idea of doing good work, but then don’t know how to go about doing it. Celebrity investments are often of-the-moment, for reasons related to public relations. It doesn’t mean someone like Mitch Winehouse can’t build a long-lasting, well-resourced, well-thought-out strategic organization, but it does take time and effort.”

Two years in, it appears that Winehouse — along with his son Alex, his ex-wife Janis (Amy’s mom; she and Mitch divorced in 1992), and his current wife Jane — have put in a profitable amount of energy and smarts to building something worthwhile. So far, the Foundation, of which Mitch is the Chairman of the Board, has allocated over £500,000 to various causes in the U.K., as well as donated to the New Orleans Jazz Orchestra and helped finance teen scholarships to the Brooklyn Conservatory of Music.

“The challenge we have is that a lot of times, it’s easy to get people involved when the celebrity’s passing is relatively recent,” notes Julie Muraco, the director of the Amy Winehouse Foundation’s U.S. arm. “But then another person of stature will pass, and a new foundation will be formed, and then another and another. There can be a lot of migration to different causes.”

The solution to that somewhat macabre problem, Muraco continues, is “to involve people who were close to Amy. We’ve got the support of Monte Lipman, who is the Chairman of Universal Records. Nas and Salaam Remi [co-producer of Amy’s Back to Black] have been involved in various ways. When you can count on people who loved Amy and knew what was important to her, it goes a long way to ensuring that there will be organizational stability.”

Mitch Winehouse, Muraco offers, “is the biggest reason for keeping the Foundation strong. He’s heavily involved in every aspect; he’s the face.”

The public perception of that face has changed over time. As Amy’s career ascended, her father worked to become a public figure in his own right. He frequently popped up in the press and on television, defending his daughter from what he characterized as hurtful inaccuracies about Amy’s very public drug- and alcohol-addiction troubles — particularly those linked to Blake Civil-Fielder, Winehouse’s ex-husband, and widely thought to be the junk-proffering villain in her story — while playing up her recovery efforts. Meanwhile, coaxed, he says, by Amy herself, he rebooted his own singing career, releasing the inconsequential Rush of Love to the Heart in 2011, the year Amy’s life bent for good, then broke.

It was — it sorta still is — hard to avoid viewing Winehouse’s attention-getting activities as at least partly fueled by nepotism. Fair or not, one needn’t look very far online to see Mitch impugned as an opportunist. Comments sections, message boards, and satirical websites are where sympathy goes to die, but the emotions that fuel them aren’t lies, exactly. Those feelings are real.

“There was an odd dichotomy in the way people thought about Mitch Winehouse,” says Alexis Petridis, the head rock and pop critic for U.K. newspaper The Guardian. “On one hand, he was clearly trying to protect his daughter, and the way he did it was by speaking through the press. On the other hand, the public thought it was a bit strange when he launched his own singer career at a period where his daughter’s life was completely haywire —he looked like he was using his daughter’s fame to grab some of the limelight for himself. It was uncomfortable to see.”

Indeed, there were times Amy herself was uncomfortable with her father’s visibility. After one of his televised appearances, the younger Winehouse tweeted, WHY don’t my dad WRITE a SONG when something bothers him instead of going on national tv? An you thought YOUR parents were embarrassing.

Since Amy’s death following a vodka binge in September 2011, Mitch has predictably become a more sympathetic figure. He used the payment he received for writing a memoir, Amy, My Daughter, to financially kickstart the Foundation, and when he shows up in the news these days, it’s to talk about charitable initiatives.

“He has remained somewhat in the public eye, but it’s for running a charity,” explains Petridis. “Clearly, what happened to his daughter was an awful thing. And he’s coming to terms with that by promoting a foundation that’s trying to be a positive force. His music career is not really on the radar, so he’s just out thought of as out there trying to honor her memory by helping people. Who can criticize that?”

It’s a fair point. But it doesn’t make it any easier to shake the emotional seesawing brought on by watching Mitch perform. The thing is, there’s been an unnatural inversion that he can’t correct: The daughterwas the star. The daughter had the potential. The daughter had the gift. The father is the one still singing.

A slender young man with a thin beard and mustache nudges me on the shoulder during a between-song lull at the Iridium. His name is Lance, and he’s a big fan of Amy Winehouse. He’s never heard Mitch sing before tonight. He was given a documentary DVD about Amy for Christmas and learned about Mitch from that. He came tonight to tap into the bloodline.

“I saw in the documentary that there was a definite connection between Amy and her dad,” he says, leaning over and speaking into my ear. “He influenced her so much.”

Mitch isn’t shy about that kind of causal thinking. Leading up to tonight’s show, his bio blurb on the club’s website promised that a ticket would buy you posthumous proximity to the source of Amy’s gift: This, it maintained, referring to Mitch, is the Winehouse musical DNA.

Lance gazes at the stage. Mitch eases into the lilting samba of Antonio Carlos Jobim’s “The Look of Love.”

“This is just….” Lance closes his eyes and searches for the word. “It’s eerie, isn’t it?”

//www.youtube.com/embed/YxQlEJ89QZY

“Sometimes I’ll read trolls saying I’m feathering my own nest,” Mitch says, speaking in the hotel lounge. “But I never sang for a month after Amy died. All the money I make after I pay the band goes straight to charity. And she would’ve wanted me to sing. She would’ve told me to stop moping about.”

Winehouse, who plays a small handful of shows every month, admits that it’s easy to draw unflattering conclusions about the motivation behind his musical career. (“If you don’t know me or anything about what matters to me, I understand you might think I’m looking to make a name.”) He also feels pride about his second go-round as a singer, boasting to me about being popular in Germany, how he has fresher arrangements than Michael Bublé, and that he’s getting ready to work on a new album (tentatively due in February 2014). I ask him who he thinks comes to see him play, and why they do it.

Winehouse exhales deeply; he only answers the question indirectly. “You just get on with it,” he says. “When people die, it’s the worst thing that can happen. Throughout my life, it seems like I’ve gone from one mourning . . . my uncle died. My aunt died. My other uncle died, and I’m not even 25 years old. Grandparents died. Life is life, and death is death. But you’ve got to find a way to cope. And if it becomes too much, you’ve got to get help. After she died, I saw a psychiatrist or clinical psychologist or whatever they’re called nowadays. There was an image that I had in my head of Amy that I didn’t want anymore. I’d rather not say what it was, but I fixed it. I can’t think of negative stuff all the time. I’ve got to move forward. Blake, for example. I don’t want to see him. I don’t want to talk to him ever again.”

He asks if he can tell me another joke.

“Okay,” says Winehouse, grinning. “There is an old Jewish joke about the Cohen brothers: Morrie Cohen dies, and at the funeral the rabbi says, ‘You know, he wasn’t a very nice man and he wasn’t very popular. The one good thing I could say about him was that his brother was worse.’ That joke is how I feel about Blake and his mother. What a piece of work she is. There was a rumor that there was going to be some nude photos, which Blake took of Amy, which was going to be published on the Internet. Well, that’s come from either him or his mother. It makes me sick.”

His eyes are wet.

“I mean, I can sit here all day and think, ‘If only I’d done this or that.’ I have to get on with life. That’s what Amy’d want me to do.”

But his voice is firm.

“However much I loved Amy, there was only so much you could do,” he says. “It’s people with an addiction: You can’t live their lives for them. You can’t be them. Amy did quit drugs. She said she didn’t want to look on her mum’s face or my face and see the disappointment. She was clean for two years and ten months before her passing. She said the same thing about alcohol, too. She said, ‘I’m quitting drinking, dad.’ Sure enough, the last five weeks and five days of her life, she didn’t drink, and then the last two days she drank an awful lot and had an accident. I can’t blame myself for it.”

He leans back in his chair and rubs the bridge of his nose. “I believe in life after death,” he says. “I believe Amy wants me to sing. And this is the advice I’d give to any parent who loses a child: You’ve got to carry on, for them. You’ve just got to carry on.”

The band eases out of another bubbly arrangement. Mitch Winehouse fiddles with the cuff of his jacket, then raises the microphone to his mouth.

“Amy loved this one,” he says, introducing the next song, Jobim’s “Meditation.” “She used to say to me, ‘How can anyone write a song like this?’ It’s so beautiful.”

Winehouse takes a sip of water and winks at a woman wearing a skull-print blouse.

“It’s about love lost,” he adds. “Is it gonna come back? Who knows?” He sings:

I will wait for you

Till the sun falls from out of the sky

For what else can I do?

I will wait for you

Meditating how sweet life will be

When you come back to me.

The song ends, and Mitch lowers his head. When he looks up, his bandleader counts off, and the musicians gallop into an up-tempo number. He snaps his fingers with one hand and jabs the air with the other. He shouts, “Swing it boys!” and again he starts to sing.