The plug of a wireless local area network (WLAN) cable pictured in front of a DSL modem in Kaufbeuren, Germany, 16 October 2015. Photo: Karl-Josef Hildenbrand/dpa | usage worldwide (Photo by Karl-Josef Hildenbrand/picture alliance via Getty Images)

INGLEWOOD, CA - FEBRUARY 19: Prince performs live at the Fabulous Forum on February 19, 1985 in Inglewood, California. (Photo by Michael Montfort/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)

Prince performs on stage on the Hit N Run-Parade Tour, Wembley Arena, London, August 1986. (Photo by Michael Putland/Getty Images)

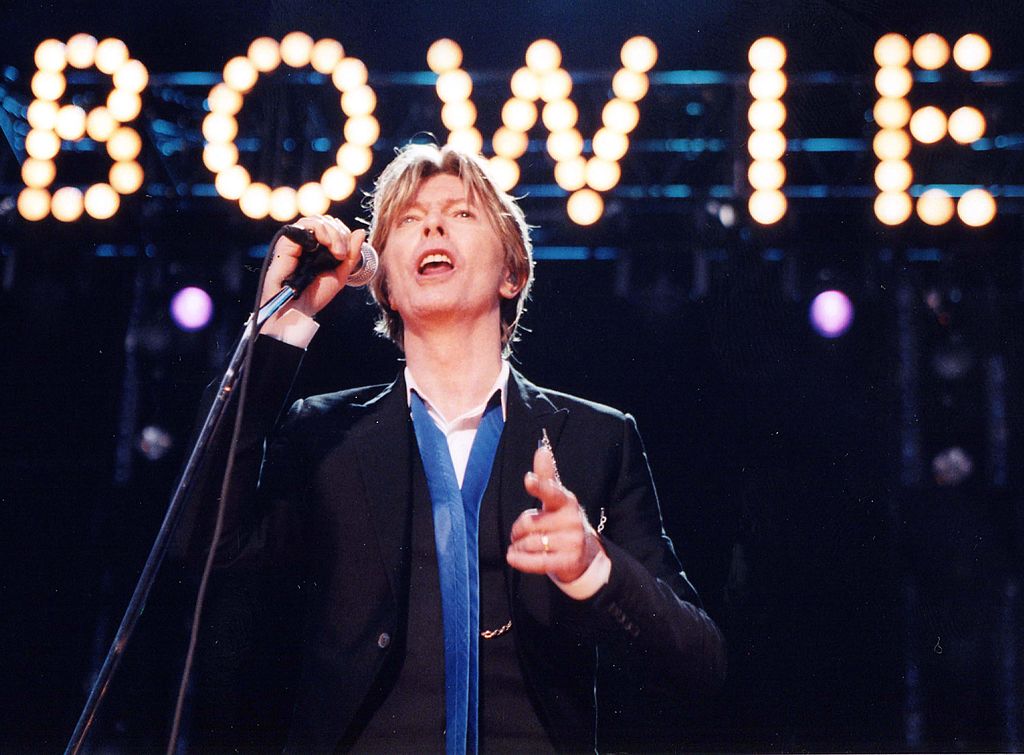

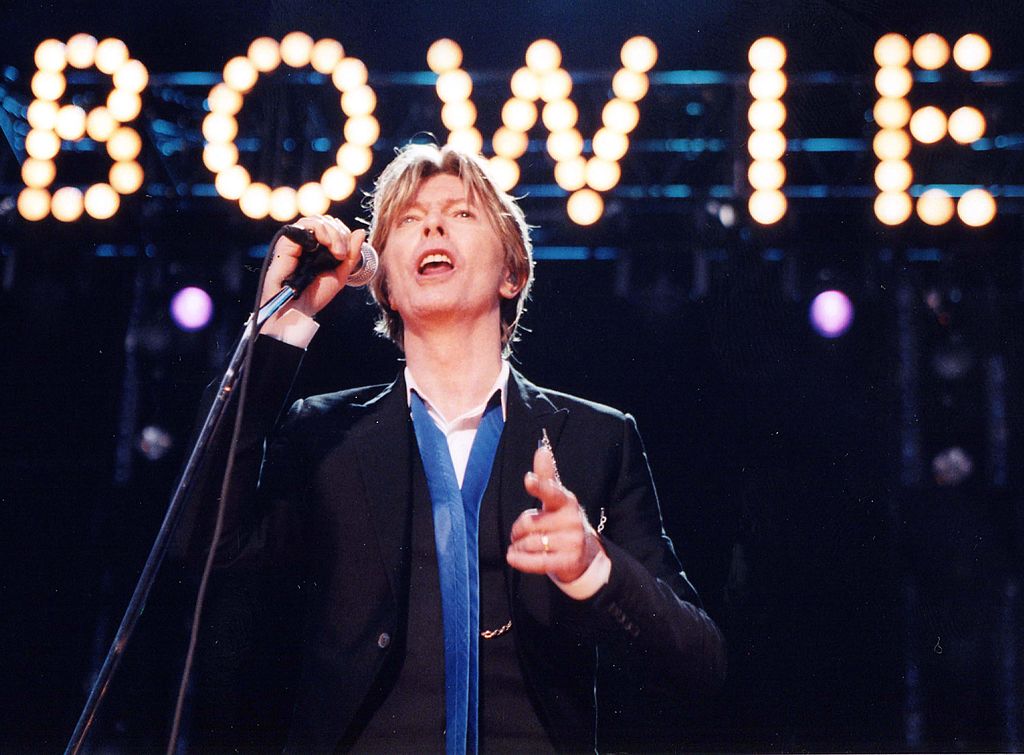

UNITED STATES - AUGUST 13: Photo of David BOWIE; performing live onstage at Verizon Amphitheater (Photo by Christina Radish/Redferns)

David Bowie On Set of "Jump They Say" Music Video, in Los Angeles California, circa March 1993. (Photo by Lester Cohen/Getty Images)

INCHEON, SOUTH KOREA - AUGUST 11: Trent Reznor of Nine Inch Nails performs live during the Incheon Pentaport Rock Festival 2018 on August 11, 2018 in Incheon, South Korea. (Photo by Han Myung-Gu/WireImage)

Trent Reznor of Nine Inch Nails rehearsing for the 1999 MTV Video Music Awards at the Metropolitan Opera House in Lincoln Center, New York City, 9/8/99. The show airs live on Thursday, September 9th at 8:00pm EST. (Photo by Frank Micelotta/ImageDirect)

MIAMI - AUGUST 28: AdRock of the Beastie Boys performs at Crobar nightclub for MTV2 presents a LIFEBEAT benefit concert August 28, 2004 Miami, Florida. (Photo by Alexander Tamargo/Getty Images)

Portrait of members of American Rap group Beastie Boys, 1987. Pictured are, from left, Mike D (born Michael Diamond), Ad-Rock (born Adam Horovitz), and MCA (born Adam Yauch, 1964 - 2012). (Photo by Lynn Goldsmith/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images)

Musician John Taylor performing at the Duran Duran Concert on March 19, 1984 at Madison Square Garden in New York City, New York. (Photo by Ron Galella, Ltd./Ron Galella Collection via Getty Images)

UNITED KINGDOM - JANUARY 01: Photo of Dave MUSTAINE and MEGADETH; Dave Mustaine (Photo by Mick Hutson/Redferns)

American singer and guitarist Dave Mustaine, of American heavy metal band Megadeth, wearing a black leather jacket over a white t-shirt, at an unspecified event with the media collected in the background, location unknown, 1990. (Photo by Vinnie Zuffante/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)

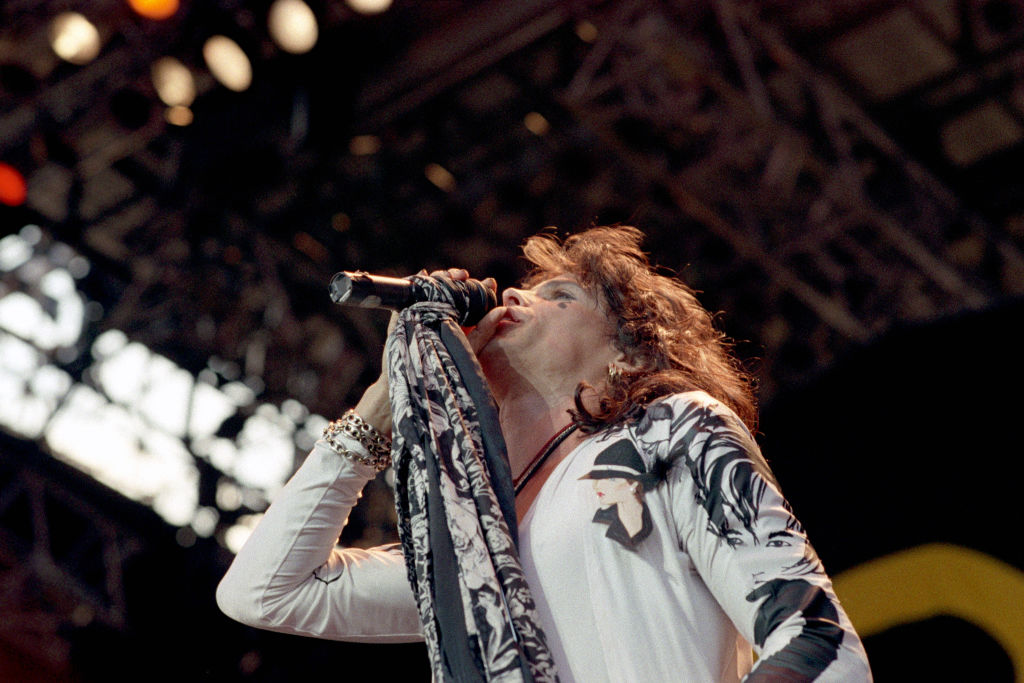

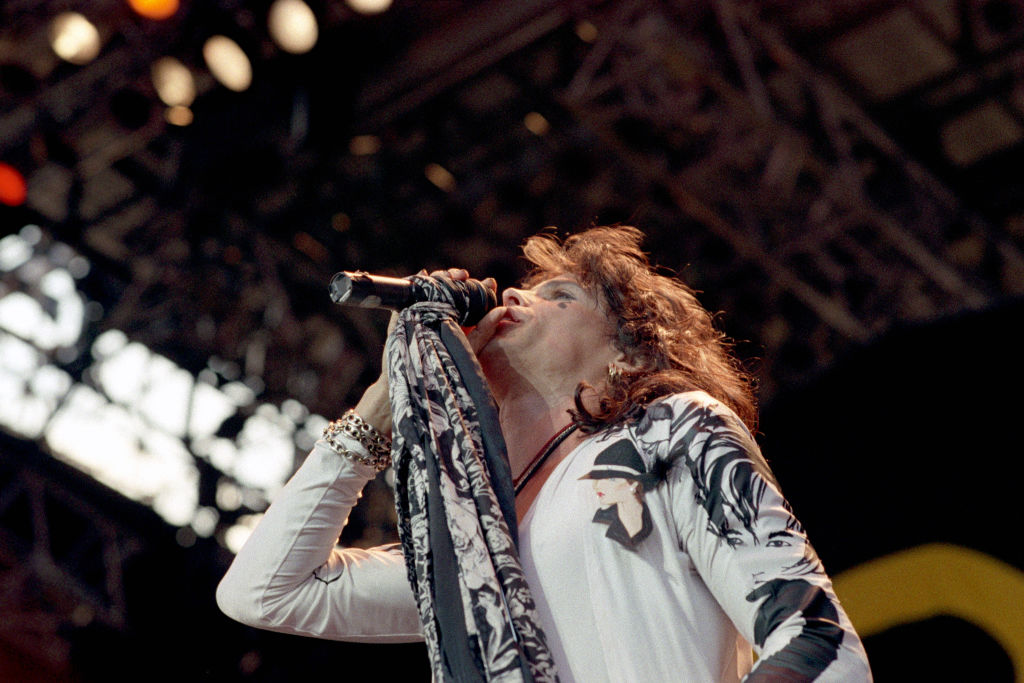

AUSTRALIA - OCTOBER 10: Photo of Tom HAMILTON and AEROSMITH and Brad WHITFORD and Joe PERRY and Joey KRAMER and Steven TYLER; L-R. Joey Kramer, Tom Hamilton, Steven Tyler, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford - posed, group shot (Photo by Bob King/Redferns)

AEROSMITH ON STAGE AT THE MONSTERS OF ROCK CONCERT AT CASTLE DONNINGTON (Photo by Paul Marriott/EMPICS via Getty Images)

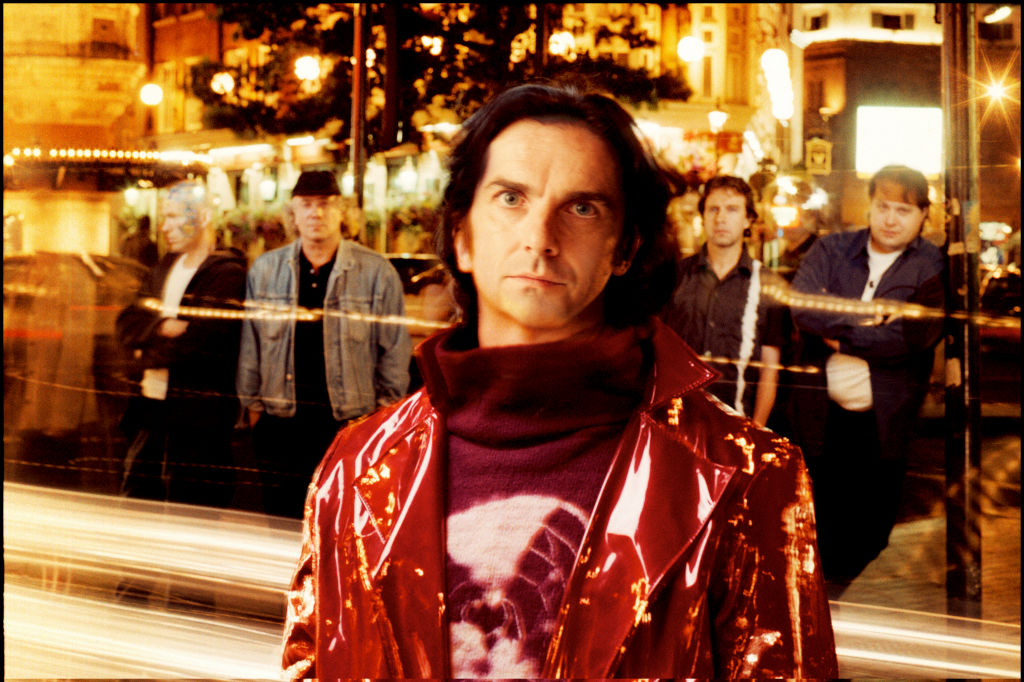

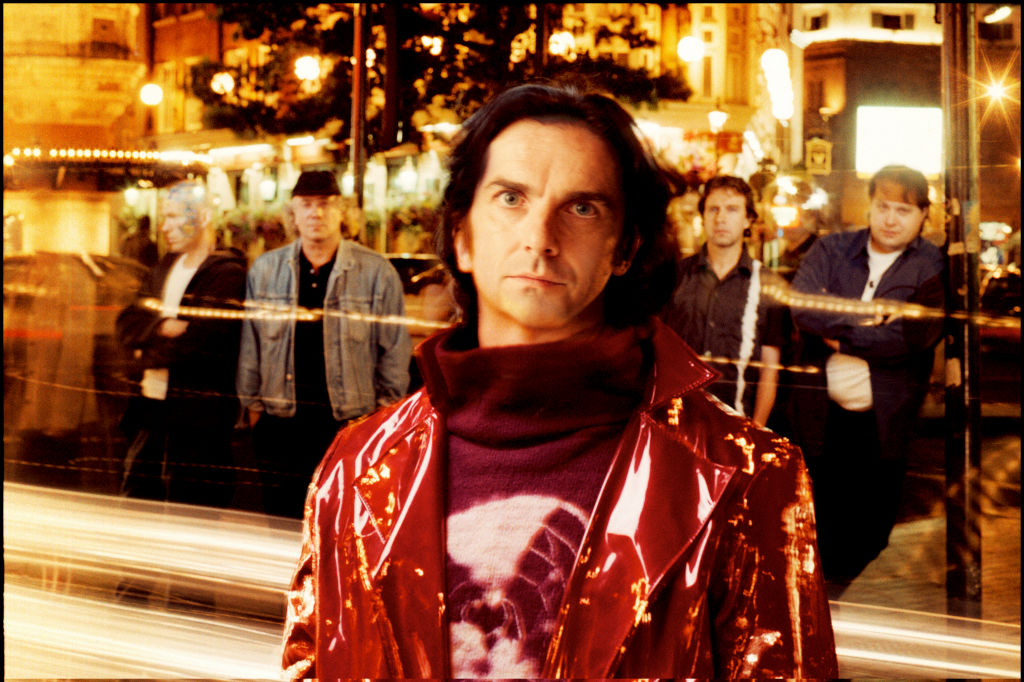

LONDON, ENGLAND - JULY 25: Steve Hogarth of Marillion performs on stage during the second day of High Voltage Festival 2010 at Victoria Park on July 25, 2010 in London, England. (Photo by Andy Sheppard/Redferns)

Marillion, portrait, London, United Kingdom, 13th July 1999. (Photo by Niels van Iperen/Getty Images)

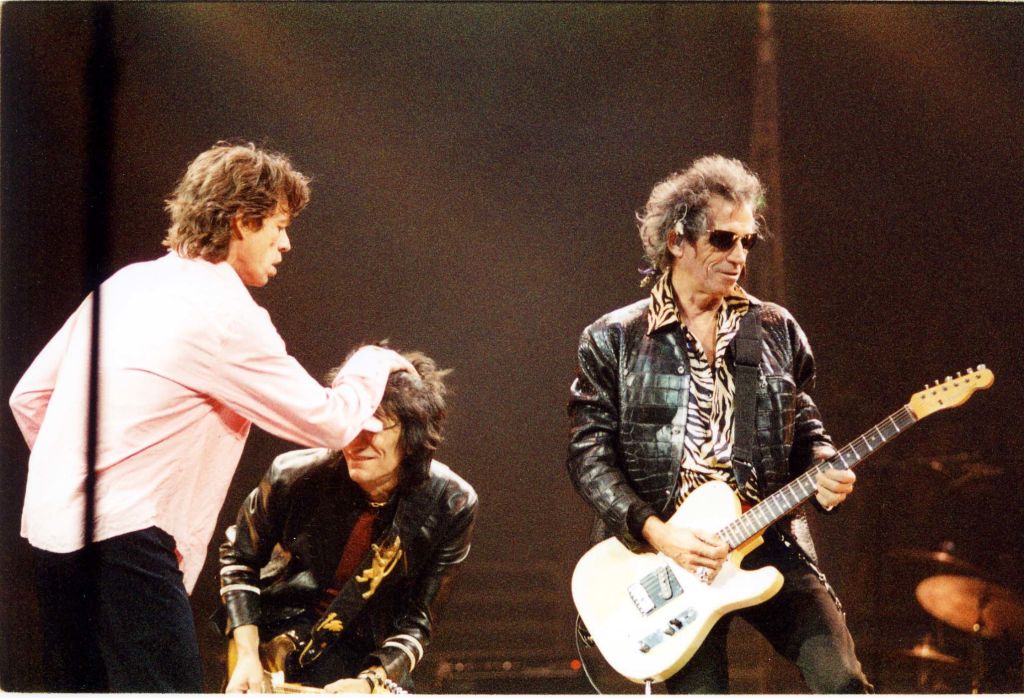

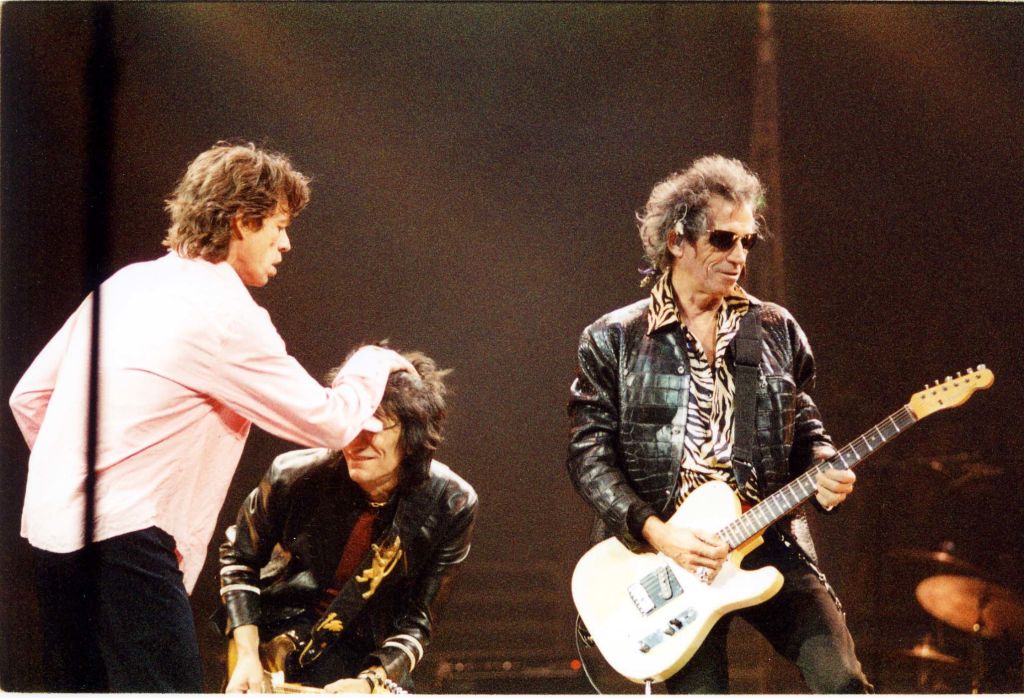

Rolling Stones In Malivield Park, The Hague, Holland, Netherlands - 1998, Mick Jagger (Photo by Brian Rasic/Getty Images)

Mick Jagger, Ron Wood and Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones - Anaheim, CA, Feb. 1999. (Photo by Jeff Kravitz/FilmMagic, Inc)

KORN during Korn "See You on the Other Side" New York City Press Conference - November 28, 2005 at Hard Rock Cafe in New York City, New York, United States. (Photo by Rob Loud/WireImage)

Jonathan Davis of Korn during Korn "See The Other Side" Concert at the Hammerstein Ballroom in New York City - November 29, 2005 at Hammerstein Ballroom in New York City, New York, United States. (Photo by Michael Loccisano/FilmMagic)

U2 during 1999 MTV EMA Arrivals at The Point Depot in Dublin, Ireland. (Photo by Jeff Kravitz/FilmMagic, Inc)

U2's Bono enjoying the World Cup final (Photo by Simon Wilkinson/EMPICS via Getty Images)