“Some extracurricular I was doing to get money went left,” says Vic Mensa. “This person double-crossed me, and robbed me.”

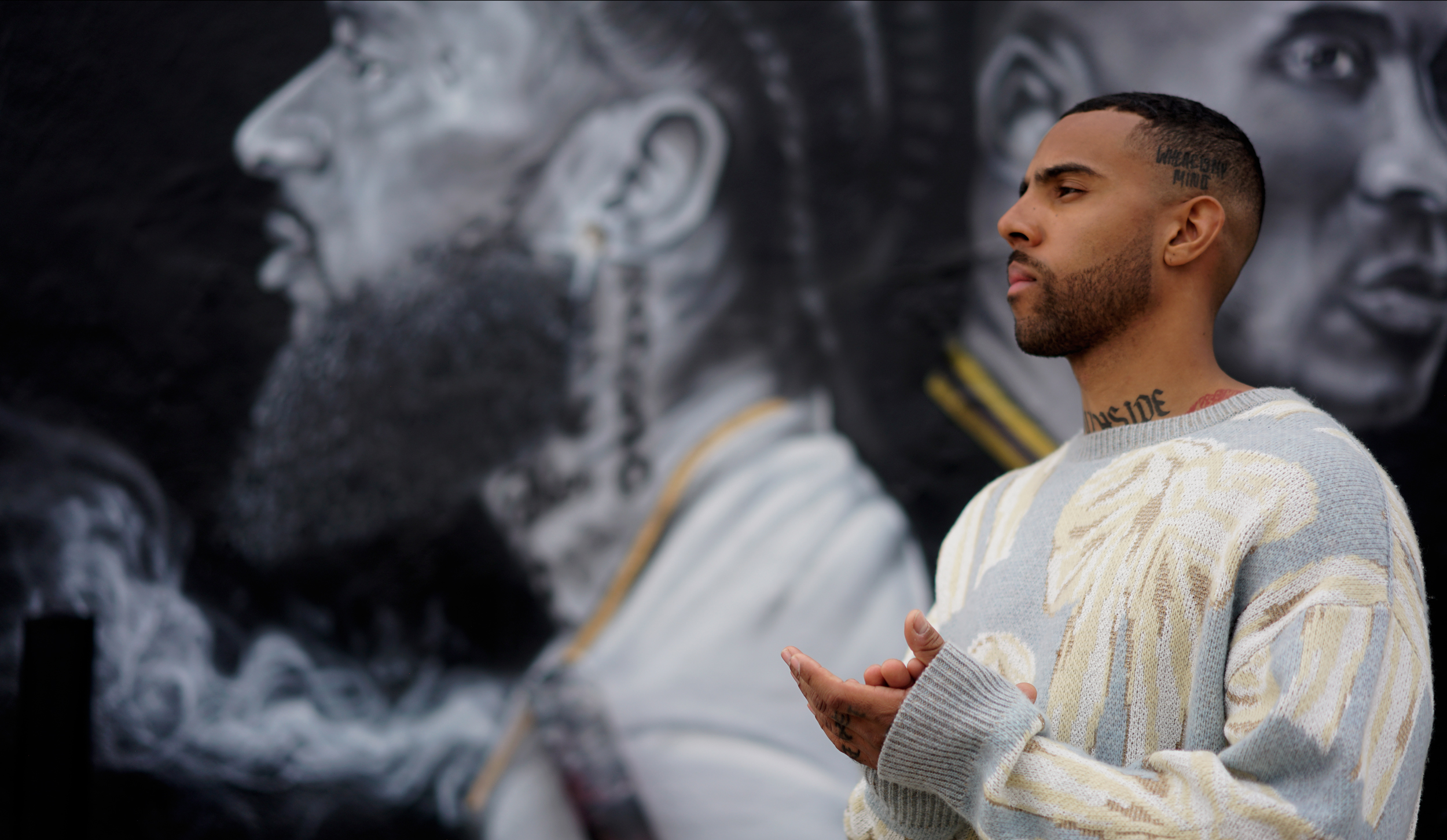

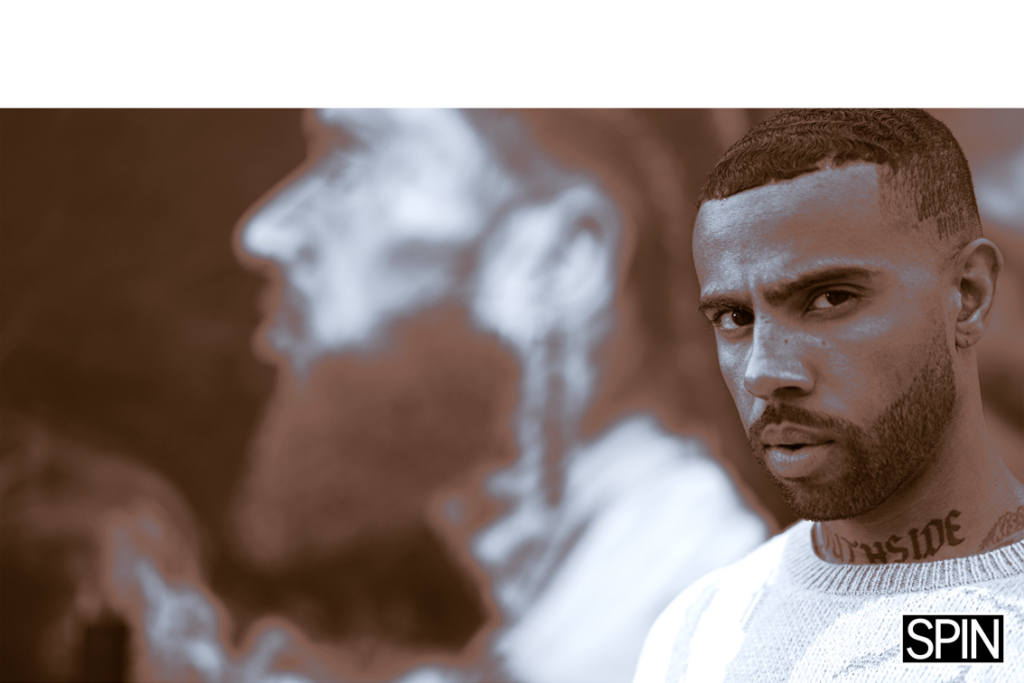

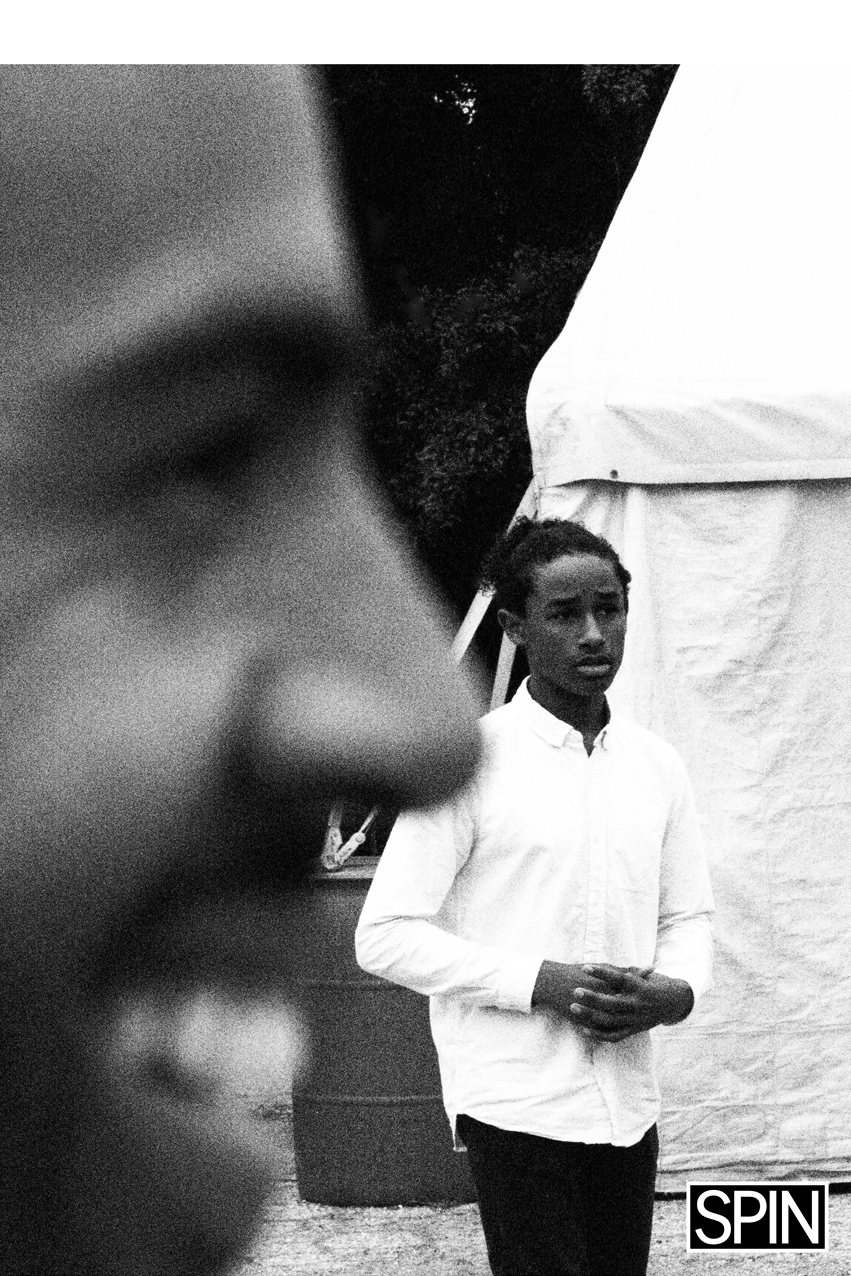

The rapper (and occasional punk-hopper) from Chicago, AKA Chiraq, where some weekends more than 100 people get shot, and where the police were outed for running a black site of extrajudicial detention and interrogation, is talking jungle, and his paths through it.

“When I found them, I beat them across the pavement in front of a large audience,” Mensa tells me. “I violently assaulted this person, and that quickly threw a wrench in my peace and my creative process — in everything –- because they knew where my studio was, and they were saying, ‘We’re going to find you over there.’”

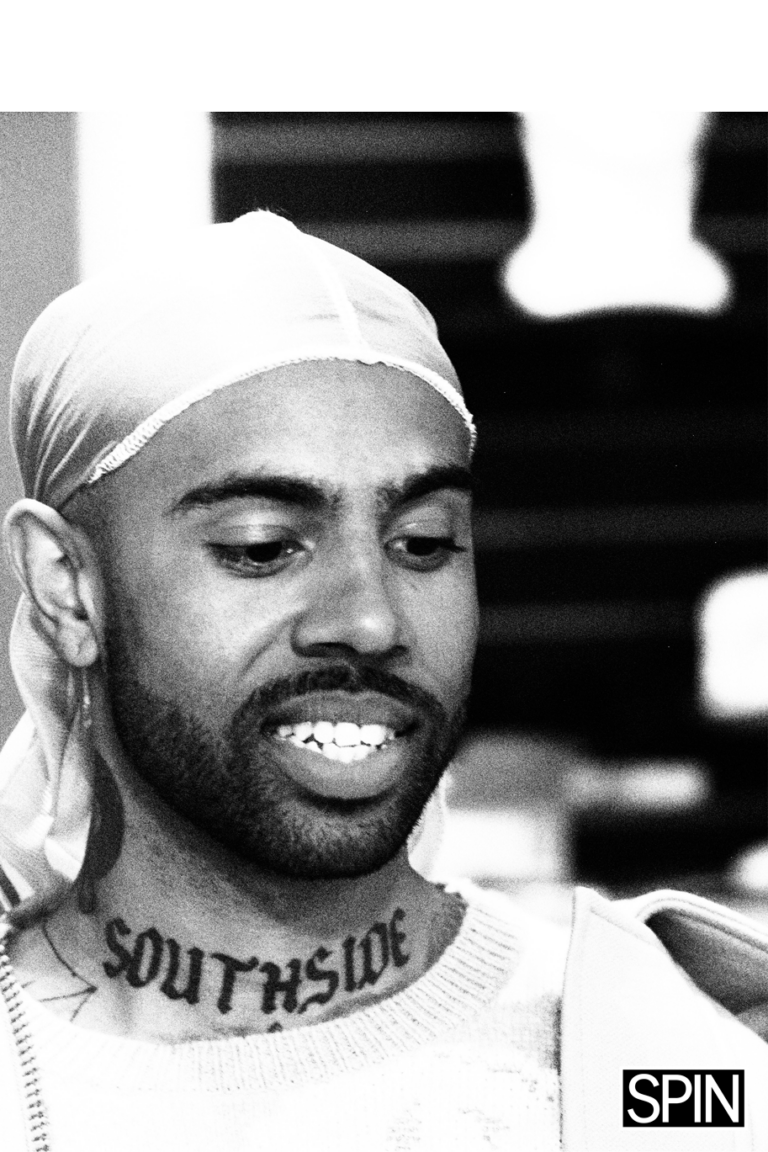

The Southside native is describing a chain reaction of stress and venom. “So now I got a gun on me 24-7, and I’m thinking, ‘Man, if I see these people, I’m a kill ‘em.’ You know? So my cortisol levels are through the roof. My amygdala is bugging. My fight-or-flight is constant, because I’ve resigned myself to potentially throw my life away. For this situation. Know what I mean? If I see these guys I’m going to kill them,” says Mensa, “cuz they may kill me. It was just so taxing.”

His preferred carry? “Something I could fit in my pocket,” he says. “I never became a gun aficionado, but mainly I would like to carry a .380 Smith and Wesson M&P.”

Mensa had previously strapped up with Austrian tools, but “after I caught my first gun case for a Glock 9 [mm], they took it,” he says, clearly disappointed.

The heat-packing, predator-prey, hustler-hustled, outlaw-inmate spiral is ghetto life, Mensa says. Existence as defined, contained, and warped by racism and its psycho-socio-skinonomics.

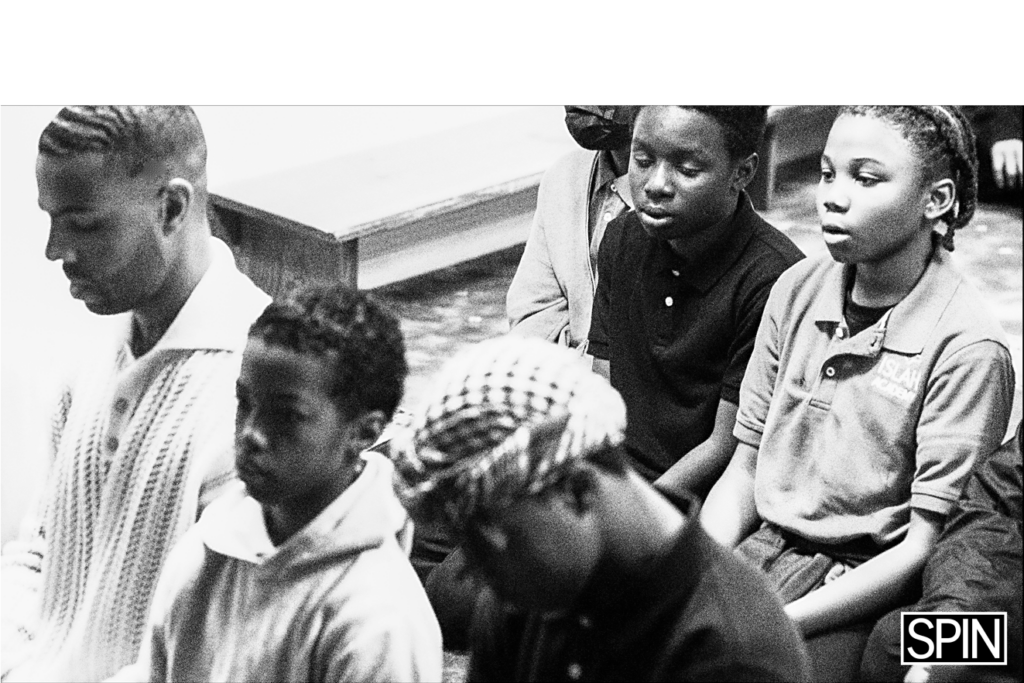

“The currency of the ghetto is violence. And the environment we live in is one in which 13-year-old girls become assassins for street organizations. And people start getting shot and killed when we’re 13, 14, 15, 16, and 17.”

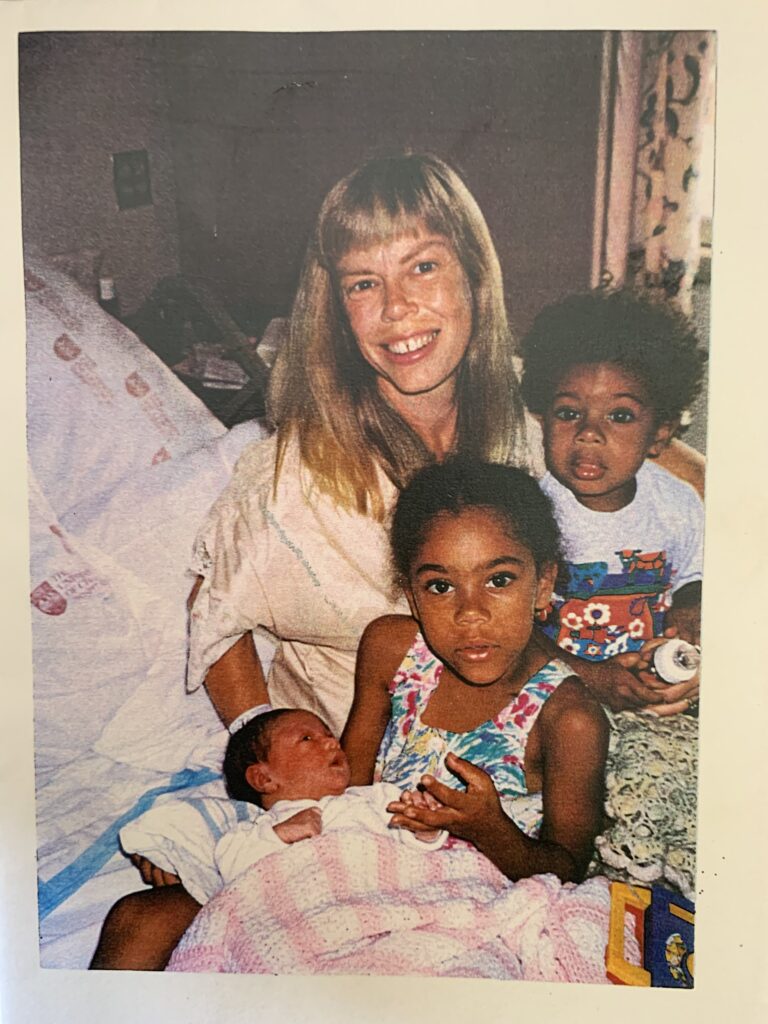

The 47th Street South Side Chicago home of Vic Mensa, now 29, was not ghetto. Born Victor Kwesi Mensah, to a Ghanaian economics professor father and an American school teacher mother, Mensa’s family was worldly, educated, and middle class. “We never were hungry, we never had to worry about where we would sleep tonight, and we lived in a nice house,” he says.

Mensa says that his father, Edward Mensah, who came to America in the ‘80s to study, was the son of a man violent towards his children. One of Edward’s siblings had fled the beatings. “My uncle was a legendary highlife musician — Chief Kofi Sammy –- a contemporary and friend of Fela Kuti. But his father beat him so badly in Ghana that he ran away and went to do his music career and didn’t come back ‘til the day my grandfather died.”

Yet the professor, rather than pass that along as a pathological inheritance, went the other way: “My dad was never violent. He’s just so wise and gentle.” Likewise his mother, Betsy: “She is just so ultimately dedicated to her family.”

Mensa counts his blessings. “It probably helped my parents that they were a little bit older. They were like 40 when they had kids, and they became amazing parents. They put their children over everything and sacrificed and sacrificed.”

However, outside the front door sat Chicago, a city Norman Mailer described as “the last of the great American cities” –- not for its pioneering music or architecture but because its people “look the pig truth in the face.”

Mensa remembers the world outside his home: “So we’re in a nice house directly across the street from a corner where men get killed, you know? Drugs are sold, and that's directly outside the window. The moment I step outside, it's cracking. And I’m naturally inclined to chaos. Outside was pretty chaotic. It wasn't a one-dimensional experience.”

One unrelenting dimension of it, nevertheless, was the law. “It definitely is the reality that being a young black boy on the south side of Chicago, you start being accosted by police, mistakenly identified, and verbally and physically abused.”

Had Vic presented like his mother, white, such an atmosphere wouldn’t have been his blighted birthright. Instead, however, much like sometimes-fellow Chicagoan Barack Obama, a darker pigmentation coming from his father marked him out as the yin to White’s yang.

He attended Whitney M. Young Magnet High School in Chicago’s Near West Side, described by the Chicago Tribune as having “superlative facilities” when it opened in 1975. Other notable alumni include Michelle Obama, Matrix-creating brothers (later turned sisters) Wachowski, and rapper Cristalle Bowen, aka Psalm One.

Young Mensa’s musical breakthrough came as the house rapper in Kids These Days, a high-flying teenage band that packed a horn section and freewheeled through hip-hop, rock, funk, and whatever else took their fancy. Even before Kids These Days’ first (and only) album, 2012’s Traphouse Rock, the band was invited to play Lollapalooza (a year after Mensa was hospitalized after getting electrocuted during his attempt to break into the festival).

Kids These Days’ trumpeter Nico Segal, aka Donnie Trumpet, also attended Whitney M. Young, as did singer and keyboardist Macie Stewart, now of Chicago rock band Finom. Both Vic and Segal studied under (handily named) English teacher Jim English, who described Mensa to the Chicago Tribune as “very, very intelligent and creative.”

After the band split in 2013, Vic grew as a commodity, performing with Damon Albarn’s Gorillaz, touring Europe with Danny Brown in 2014, and rapping in 2015 on Kanye West’s dream-ramble of a song, “Wolves.” Mensa performed an abridged version of “Wolves” on Saturday Night Live with West and Sia. Soon after he signed with Jay-Z’s label, Roc Nation. He recorded with Skrillex, released more solo work, and later toured Europe again, this time as Justin Bieber’s opening act, and opened for Beyonce. Big artists recorded with him, including Pharrell Williams on the self-lacerating “Wings” from Mensa’s debut album, 2017’s loftily titled The Autobiography. A second album is due out this summer, following his January single, “Strawberry Louis Vuitton.”

His work developed a streak that was rampagingly political. At major concerts, with police in attendance, he turned in wild performances of “16 Shots,” his song about the murder of black teen Laquan McDonald by a Chicago cop. In a twist on Public Enemy’s S1W crew, Mensa was joined onstage by rows of dancers clad and helmeted like riot cops.

Being America’s yin can mean growing up in a different country to many others. “We live in an occupied, martial-law, police state. That’s the reality,” he says. While he experienced racism and its internalized devaluations from an early age, and spent his childhood observing the ways of South Side streetlife, he says it was when he reached adolescence that state power turned its gaze upon him and got rough. Like nitrous hitting a V8.

“Once I became a target of physical police violence — and I'm coming from a pretty insecure mind frame, and I live in this very violent place –- well, I just became a very violent person, you know?”

Before that, Mensa was in the ghetto. Now, with puberty’s rites of passage for a Black male including arbitrary humiliation or worse by police, the ghetto enters him. Yet, in the fallen world of occupation and its discontents, wrangles with the police force can be a sideshow.

“Honestly, that's like sharks in the water or lions in the jungle. There's a few of 'em and you gotta watch out for 'em, but there's way more hyenas and jackals,” says Mensa. “The police are not your biggest issue. They may be the definitive factor on if you live or die today, but you're gonna deal with much more run of the mill violence from your own kind. Because that's just the psyche and the programming of our communities. So it's like you as a young black man learn that you must become the aggressor unless you wanna be a victim,” says Mensa. “And so that becomes the color of all interactions and all conversations.”

The color, this tendency in him to spill claret, is something he says he works to rein in, “to this day. I’m almost 30 years old and I'm still learning how to un-program that, because it’s so deeply dialed into me to feel threat and to match that by feeling the capacity for violence and murder.”

Especially on the streets of America’s murder capital, where homicides in the last several years total in the thousands. “That's just the reality for us, The environment is what it is.”

Some of that environment, Mensa argues, is a deliberate, brutal exercise in social engineering.

“The thing about Chicago is that Chicago is just a microcosm for Everyhood, USA. Chicago is the site of the biggest public housing experiment in America,” Mensa says That's why they call it the projects. It’s a science experiment, putting poor people on top of each other, zoned into specifically disenfranchised areas and kept from collaborating and being involved in resourced communities. And then when that science project has reached its apex, you tear it down and watch the fruits of your terrible labor scatter. And however many years later that it's been, you wonder why Chicago's always in the news for a hundred shootings in a weekend. It was the projects. They manufactured it to be this way.

“America is so skilled in amnesia,” he says. “After it's been a decade or two decades, or a hundred years, people in power just act stupid. Like they don't know how the present day happened.

“That's how you steal on a gigantic level. You feign ignorance. That's the only way you can efficiently rob people of their humanity and rob nations of their wealth: by pretending that you are not currently doing it and you didn't do it in the past. That's the colonial formula. Everywhere America goes, and right here on American soil.”

Outraged by the police parking a bait truck in a poor community — “the police in Chicago escorted a truck full of Air Force 1 sneakers and left it open” — and then standing off to watch and arrest anyone tempted to steal it, Vic Mensa ran with an idea put to him by Anwar Hadid and countered with an “anti-bait truck” that rolled into impoverished areas giving out shoes. “We gave away around 15,000 pairs of shoes — probably $1 million worth.”

Police tactics like baiting poor Black people strike Mensa as rubbing African Americans’ faces in how low they have been taken in the historical continuum. “I just watched a documentary called Descendant, and now I’m reading the book. It’s about the last kidnapped Africans brought to America as slaves. It's ill.

“And it's crazy because it's really not long ago at all — only 150 years. And the family that was responsible for kidnapping the Africans, now living wealthily on a $30 or 40 million estate and real estate trust, acts like they don't have any culpability for the destitute condition of the descendants of the people that just 150 years ago they stole from Africa and enslaved. It's the story of America.”

Books matter to Mensa, whose Books Before Bars program sends reading matter to Illinois prisoners. He credits Frantz Fanon’s 1961 incendiary tome, Wretched of the Earth, with expanding his awareness of how colonization instills pathological divisions in the resulting societies, which cast the colonizers and their descendants as an inherently superior and thus rightfully dominant breed, and the colonized as their natural inferiors.

People get more than brainwashed; they get soul-stained.

“Wretched of the Earth really spoke to me because I am militant in spirit and in action,” says Vic, who first read the book around 2016.

Fanon was a Black colonial combat veteran of the Free French Army during World War II, who was disgusted by the racism he experienced from even anti-Fascist Europeans. He became a psychiatrist, philosopher, writer, revolutionary, Marxist, Pan Africanist, and champion of decolonization.

One of his admirers was Kwame Nkrumah, the man who in 1957 led the West African nation of Ghana to independence from the United Kingdom. Invited by Nkrumah to speak in 1958 at the All-African Peoples’ Conference in newly independent Ghana, Fanon preached the use of force to throw off European domination. His message of militancy and violence struck a chord with Black Americans increasingly dissatisfied with civil disobedience in the face of staunch, widespread racism and the apartheid systems which persisted in the U.S. Bobby Seale, co-founder of the Black Panthers, credited Fanon as an inspiration.

Vic, in turns, cites the Panthers as being one of the “foundational building blocks of my worldview,” particularly in the discrepancy between its ragtag domestic depiction here by white society, and the international standing it gained, which included opening an office in Algiers after the government of Algeria severed diplomatic relations with Washington.

“What the Black Panther Party recognized in that moment was that the freedom of Black people globally is intrinsically connected,” Mensa says. “It can't be separated.”

Mensa works at decolonizing himself via sobriety, via Islam, via psychedelics, via meditation, via psychotherapy, by reading, by pursuits intellectual, ideological, artistic, and more.

His liberation quest includes regular time in Ghana, where he funds the drilling of boreholes to provide impoverished communities with clean drinking water, and where in January this year he launched the Black Star Line Festival, along with co-founder, high school classmate, and fellow-Ghanaian American, Chancelor Bennett, aka Chance the Rapper.

Named after a steamship corporation started by Marcus Garvey, Jamaica’s Black-separatist dynamo, the Black Star Line Festival is a week of concerts and events in the capital, Accra, aimed at locals but also intended to draw to Ghana hip-hop artists from across the global African diaspora.

“I started to look at the landscape of Black artistry and realize that here's this inexplicable gap in connection: You have the most ubiquitous form of communication on the planet, which I believe is hip-hop, yet the the practitioners of it don’t have any relationship with the continent of their origin,” says Mensa.

In his humble opinion, Ghanaian hip-hop has come along in spades from the early years of his times in-country. “When I was a kid, the dominant music of the airways in Ghana was this hip-hop evolution of highlife called hiplife. It was very niche, though, compared to what I was listening to in America. So the hip-hop in Ghana felt worlds away and also, in a way, kind of behind. It didn't sound like I could play this for my homies in America and they'd be like, ‘Oh, this is dope.’

“In the years since, hip-hop and Afrobeat and Ghanaian music in general have progressed so much: to the point where there’s now Ghanaian drill music that’s ear-splittingly hard. It really can kind of stand up with the level of American hip-hop. Not to say that America is the barometer for musical value, but hip-hop is obviously an American art form. So it's like you always judge things on that scale.”

His first experience of Ghana was a trip at the age of 11 to his father’s homeland. “The vast majority of the family remained in Ghana in a place in an eastern region called Koforidua,” says Vic. “They live in an area that is referred to as a zongo. Basically, zongos are West African hoods. It's a colloquialism for a form of slums that exist from Ghana to Nigeria.

“It was a complete shock to the system. I was scared, honestly. Because I'd never been somewhere that was so vastly different. When I arrived it was night and it was loud, and I couldn't understand what anybody was saying.

“But the day broke, and I met my family. It was beautiful directly after it was frightening because I met my grandmother for the first time. I never had a conversation with her. She didn't speak English, and I didn't speak Twi [a Ghanaian language], but the depth of love is so real. It taught me a lesson that has come around many times in my life: that humanity is so much deeper than words, or religions, or politics.”

More recently, and since his grandmother’s death, Mensa has spoken with her after ingesting secreted toxin of the Sonoran desert toad. “It was the first time I was ever really hearing her speak to me,” says Mensa. “She explained that much of the fear that I carry in my life is not mine. It is ancestral, and it was handed down to me as the descendant of a colonized people.”

His beliefs shifted with these visions of his grandmother: “She was telling me, ‘You inherited fear from me. Because I was enslaved. We were enslaved. We were colonized, and we were dominated, and our families were ripped apart. And that exists in all of us.’”

Her lasting message, Mensa says, was not to be led by that fear. “‘When you think of me,’” Mensa remembers her saying, “‘don't think of fear. Think of my love. Be motivated and guided by my love, not my fear.”

Over the years, the rapper’s approach to drugs has changed. “The first drug I really felt dependent on was mushrooms,” he says. “I started doing them abusively. Probably 100 times a year when I was like 19. But it wasn't soul-searching. I started to lean on it as a creative crutch, and eventually it just stopped working and I started having bad trips — I would feel like my throat was closing and I was dying.”

Mensa says he then switched to MDMA. “In the pursuit of boosted creativity I started doing a lot of molly and ecstasy. I was going to the bathroom in the middle of a studio session and railing molly with the powder falling on the ground. And I'm rolling up a dollar bill, on my hands and knees railing it off the bathroom floor — definitely with piss mixed up in it,” says Mensa. “That stopped working, and just tanked my serotonin.”

From MDMA, Mensa turned to amphetamines. “When the molly crashed, I was so depressed and started snorting Adderall. Then that stopped working.”

Everything stopped working, he says. “I would use each drug to the max until it stopped working. And then I was feeling like I couldn't create, because I needed these drugs but the drugs weren't working. And so I was hell bent on killing myself. I was on a full warpath of suicide.”

The path led to the precipice. “Guns and cliffs.” he says softly. “Guns and cliffs.”

And then, in the mountains of San Diego, came a ritual with the uncompromising Amazonian brew ayahuasca, the DMT-packing “vine of the dead.”

“When I did that first ayahuasca ceremony, my question for the medicine was: ‘Why do I feel so much pain?’ And I had a vision of seeing my mother's blonde hair from my 5-year-old eyes. A higher voice came to me and said, ‘I used to want blue eyes. That is the root of my pain.’”

“I thought that was so revealing,” says Mensa. “It's the first place I can really pinpoint it to within this lifetime: a sense of unworthiness because of not looking like my parents.”

The particularities of Vic Mensa’s being –- Black child of a White mother; South Side boy with not an African-American dad but a flat-out African dad — have at times positioned Mensa off-kilter in relation to those around him.

“When I was a kid, I felt like I couldn't really fit in,” he says. “I would be not accepted as Black because I'm African. So I didn't know or understand Black culture in that way, but then there's no chance I would be accepted as White. That made me feel sadness, and I developed a dark side.”

While going through old stuff that his mother had held onto, he found notebooks of his from when he was 6 years old. “I’m flipping through ‘em and I find pages — it’s just: ‘I hate myself. I hate myself. I hate myself. I want to kill myself.’ And drawings of decapitation.” The notebooks fit with the revelations of spirit medicine. “Whatever you are hiding from or whatever makes you really uncomfortable, the darkest secrets, ayahuasca is going to make you face them. It’s incredibly difficult,” he says. “You'll be retching and vomiting and crying, but ultimately feel so much gratitude for having to go through all those difficulties.”

This gave him not only insight but self-respect for how much resilience he must have. “I’m a fighter. I appreciate myself for being able to have a substantial life and accomplish many things while having this deep-seated internal resistance. Especially knowing how many times I remember feeling like I wouldn’t make it to next year. Finding out I’ve been dealing with that since I was 6 — it gave me a lot of grace for myself.”

Ayahuasca delivered to Mensa a “deep knowing that I had to implement discipline into my life. I was experiencing visions of a wolf; I was becoming the wolf, and I started thinking about how to tame the wolf.

“I'm intrinsically very aggressive, very protective, sometimes violent. I’m a powerful person, and as I've learned to change my behavior to be constructive and positive, to tame it, sometimes I can feel I'm losing some of that vicious nature.”

His journey down the vine of the dead schooled him “in the value of patience and discipline.”

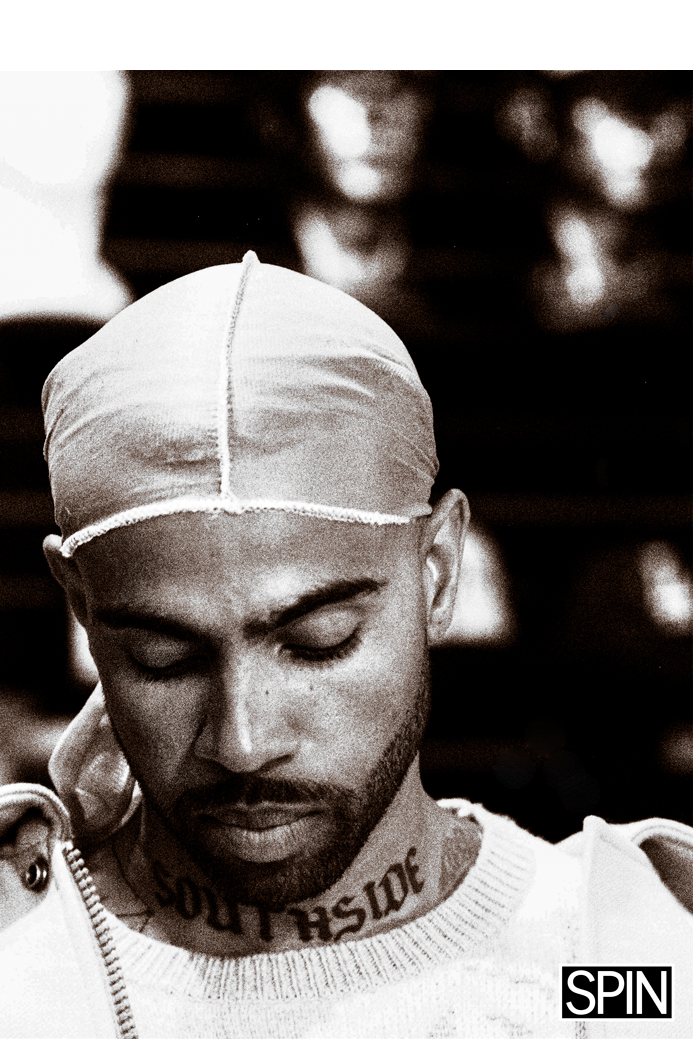

And thus: Islam.

First, though, came missteps: dishing out the beating recounted at the bloody start of this tale, and a month-long cocaine bender.

Inspired by an individual who seemed to have his shit tight, Mensa then visited a house of submission.

“I went to the mosque — I was really dealing with a lot at the time, you know? I had so much going on –- and the imam is delivering his khutbah [sermon]. He's saying that there's two types of people in this world. There are people who are struggling: They're struggling financially, they're struggling mentally, they're struggling in the streets with violence, they're struggling with drugs, their relationships are damaged. And then there are people that are on the right path.”

A straightforward message, but one that hit home to Victor Kwesi Mensah. “It was deep to me, cuz I was struggling with all those things at the time, and I had somebody trying to kill me, and I'm struggling with money and I'm struggling with depression. I'm struggling.”

The clarity of Islam hit. “So I honestly just hit the mat and prayed in earnest for the first time in my life. Really prayed with the belief that I was praying to an entity, you know? I was telling God, ‘Man, like, look, if you can get me through this, I will change my life.’”

Perhaps Allah doesn’t do tricks on demand, though, as “about a week later I ended up drunk driving, totalling a Range Rover with a dirty pistol in the car,” says Mensa. “And I have multiple gun cases already. That would've been enough to put me away for a little while for sure. But I got blessed. I had insurance on the car; my friends came; they took care of everything. I was honestly saved by the grace of God. So I just leaned into Islam.”

He quit a bunch of vices, from drinking to smoking to shoplifting (for which he has previously claimed to have been falsely accused).

“I stopped stealing gum from 7-11s. I stopped finessing,” he says. “My mind has always been programmed to finesse, because that’s how I grew up: being an outcast and being a young Black boy, being marginalized and oppressed, I developed a mentality of the world, you know? If I can get over in one way or another, if I can steal this instead of buying it, let me do it. Cuz the world doesn't care about me.”

But Islam taught Mensa that if he doesn’t finesse, if he doesn’t cut corners, then more will be given to him. Most importantly, he will not be subject to the consequences of his own waywardness: “I started to realize that I was bringing so much difficulty into my life and constantly dealing with so many negative situations of my own design.” He had long respected the Nation of Islam in Chicago, but nevertheless had reservations about a religion that came from Arabs, who, historically, had “enslaved my people.”

Nevertheless, “I'm not gonna lie to you, I love it, bro,” Mensa says. “Because not only is it a practice of constant humility, it’s a constant reminder. I’ll be doing music or just hustling, and sometimes I’ll get frustrated. But when I get that call to prayer — when I heed that call to prayer –- it’s me taking a moment away from whatever I was doing to be thankful. It takes so much weight off me. I spend time being grateful for the blessings of my life.”

The blessings apparently include the ability to transport his mind peacefully beyond the confines of detention facilities, as he learned last year after being arrested at Dulles Airport in Virginia, flying in from Ghana with LSD and magic mushrooms. The psychedelics were for microdosing while weaning himself off antidepressants, he says.

He ultimately copped a year’s probation on a misdemeanor possession charge. “They might have made me do some, I don't know, fucking drug counseling or some shit, but I don't do drugs anyway, you know?” says Mensa.

Asked if getting busted and detained had thrown him back into depression, Mensa says his time in the custody of the Metropolitan Washington Airport Authority “was cool.”

“Honestly, I was so deep in my meditation at the time,” he says. “Although I was incarcerated I was doing deep hour-and-30-minute-long meditations that transported me beyond the walls of the jail cell. At no point in time did I allow any doubtful or negative thoughts to really exist, even when it looked like I might have to be in there for three months. I was in such a disciplined, powerful space that I didn't really have any trouble.

“I just started to thank God, for the blessing in the form of a lesson. Obviously it's whacked to have to go to jail and be plastered all across global news. But I think it's pretty beautiful that, just a few months after that, I was able to launch the first black-owned legal cannabis company in my state.” He’s talking about his line of weed, 93 Boyz.

“That's plant medicine.”

--

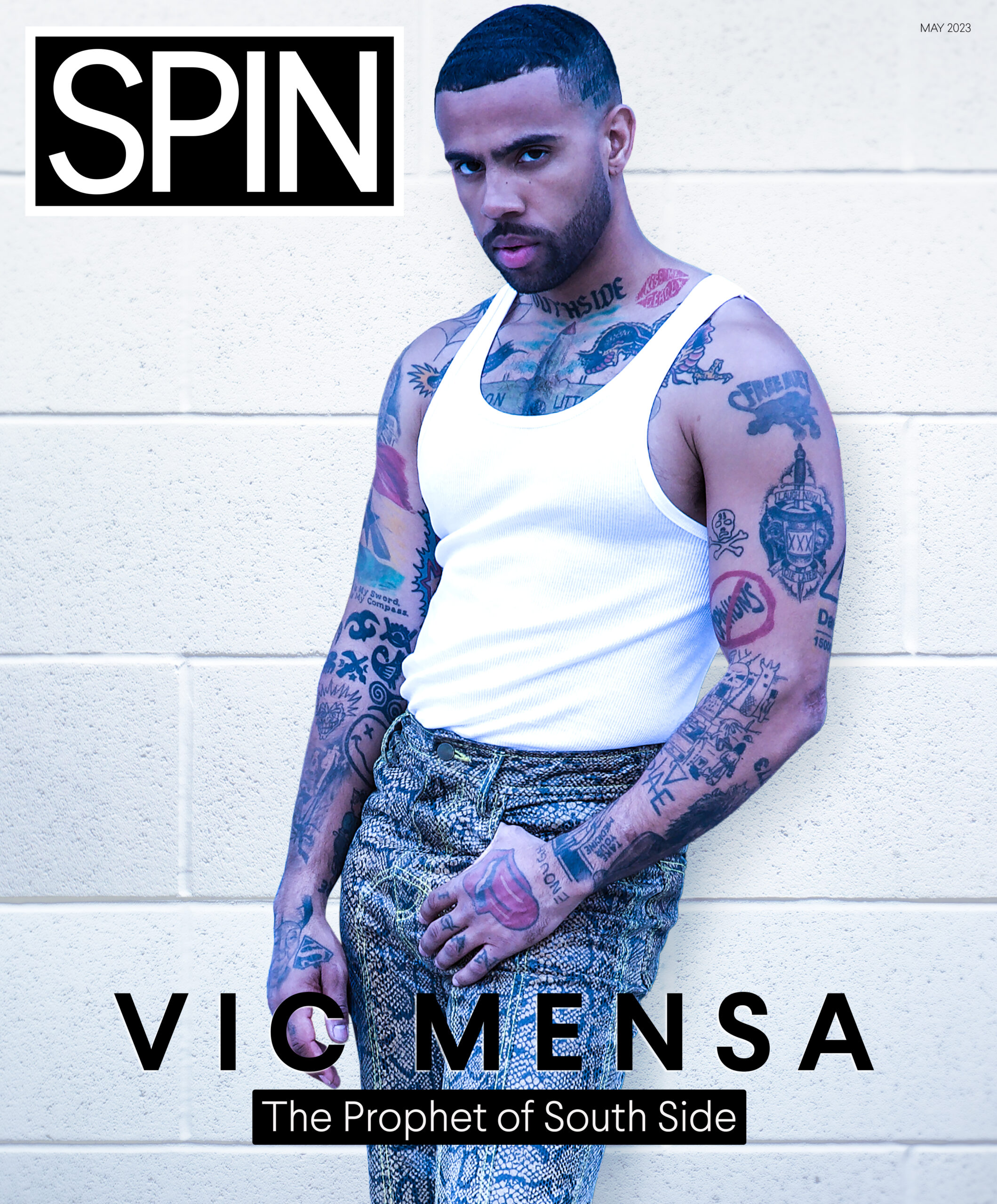

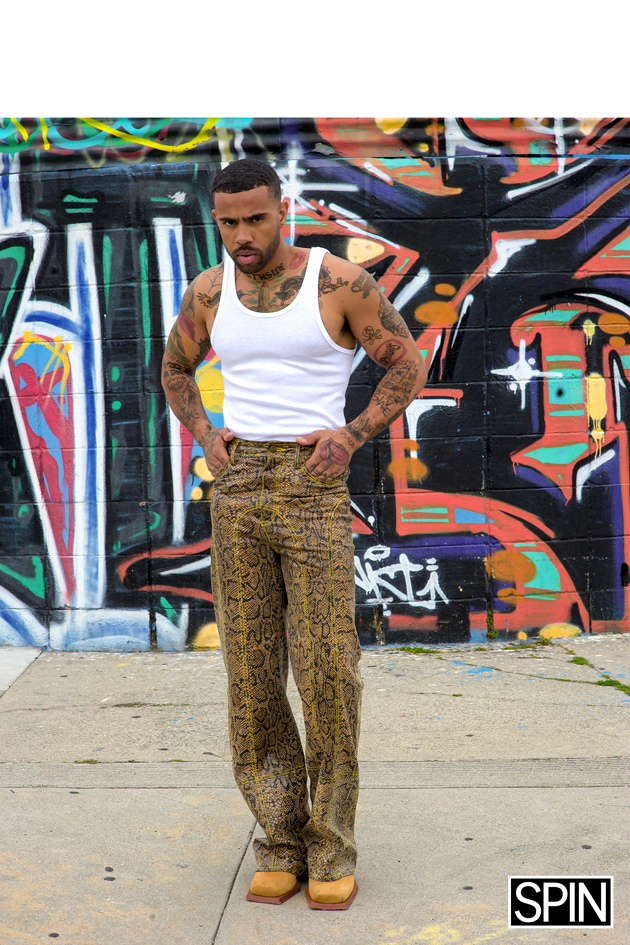

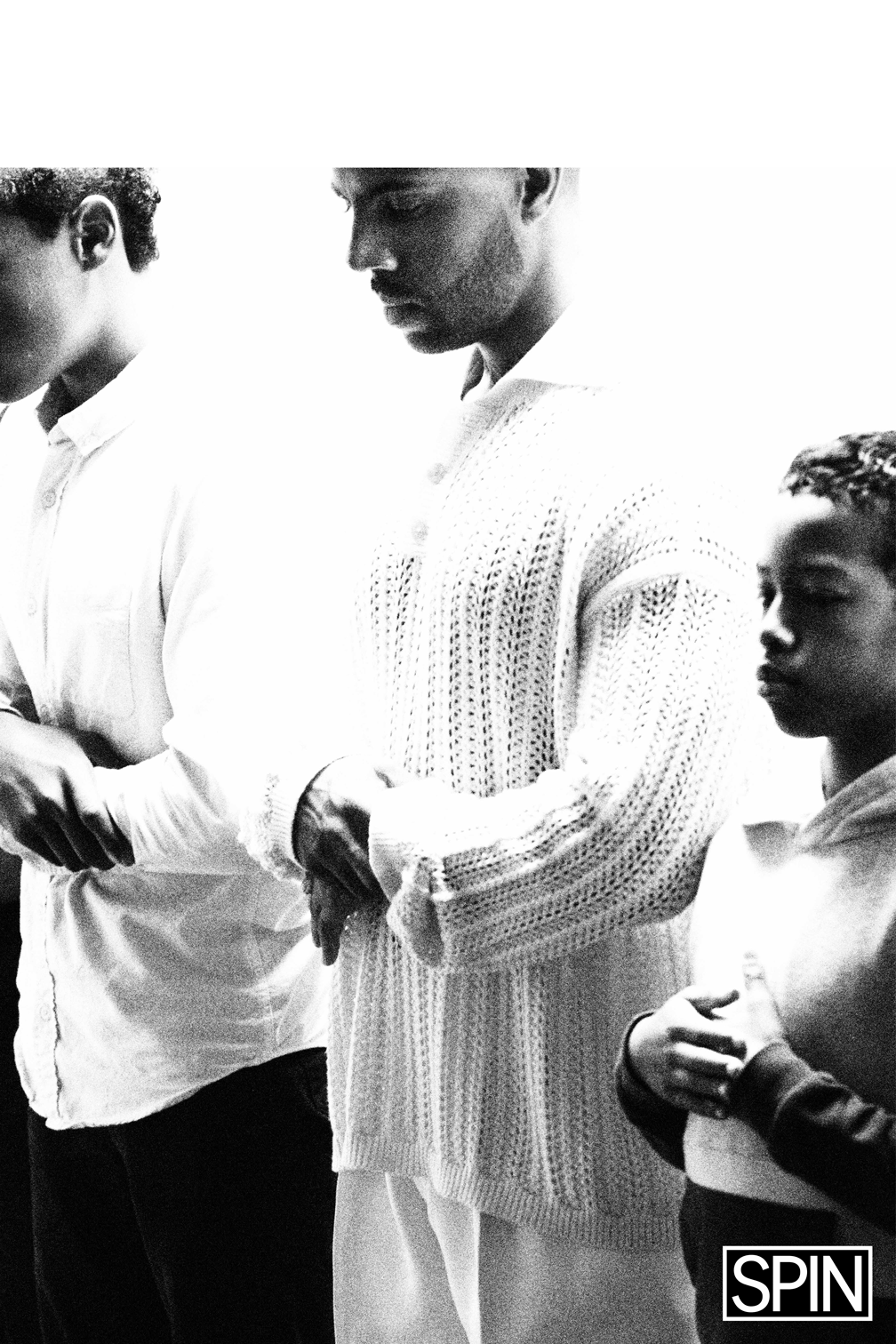

Fashion Stylist: Jason Rembert

Assistant Stylists: Jarrett Meilleur & Orville Reid

Make-up/Groomer: Marcela Osegueda