His album sales had been declining for a few years, and his finances were a wreck. Playing ball with the country establishment hadn’t worked. With its Queens of the Stone Age-meets-Pink Floyd blend of moody, heavy rock, Black Ribbons was supposed to set him free. But the crowd wasn’t feeling it. Earlier in the tour, Jennings thought he heard an audience member praise the songwriter for "speaking the truth" — instead, the fan yelled out that the singer didn't "support the troops" due to the provocative messaging of Black Ribbons. The fan was kicked out of the show but was pacing back and forth outside the venue waiting for the singer, making for a potentially perilous situation.

Despite having a solo hit with "4th of July" five years earlier, Shooter was constantly compared to his parents: Waylon Jennings and Jessi Colter. And that April night felt like the final fizzling out.

Something had to give — and it did.

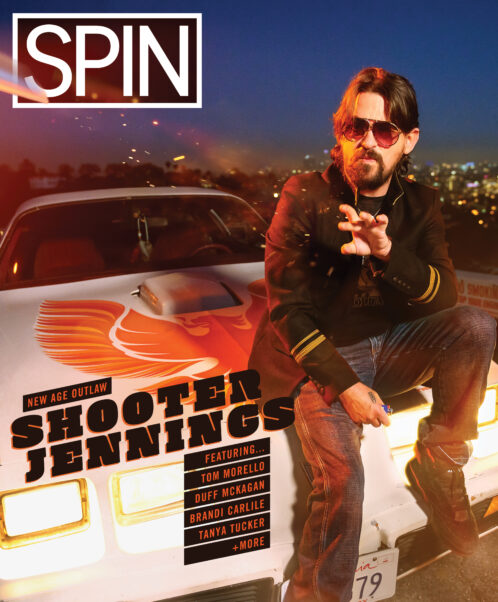

Since then, Shooter Jennings got married, produced Grammy-winning albums for Brandi Carlile and Tanya Tucker and crossed paths with everyone from Rage Against the Machine vet Tom Morello to Guns N' Roses’ Duff McKagan. And his musical career — which began with producing industrial tracks that initially mystified his country-royalty parents — hits another peak with Marilyn Manson's We Are Chaos, an album years in the making.

But the journey wasn’t easy.

Born in a Nashville hospital in May 1979, Waylon Albright Jennings couldn’t wait for a diaper and let one fly at a nurse.

”Looks like we have a shooter here,” the elder Waylon said to his wife, fellow outlaw country singer Jessi Colter, giving their son a nickname the boy would learn to hate. Johnny Cash was one of the first people to meet the newborn.

Still, his mother preferred the nickname to the alternative.

“I could not call a little baby Waylon,” Colter says. “I had the big Waylon, so I couldn’t do it.”

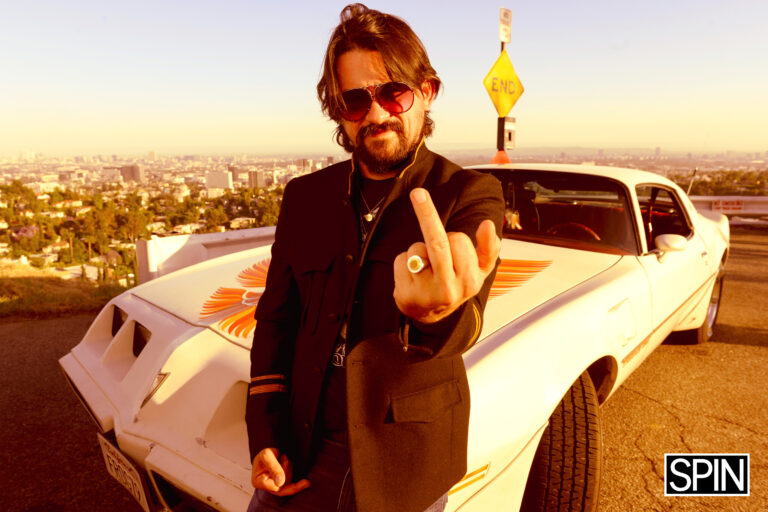

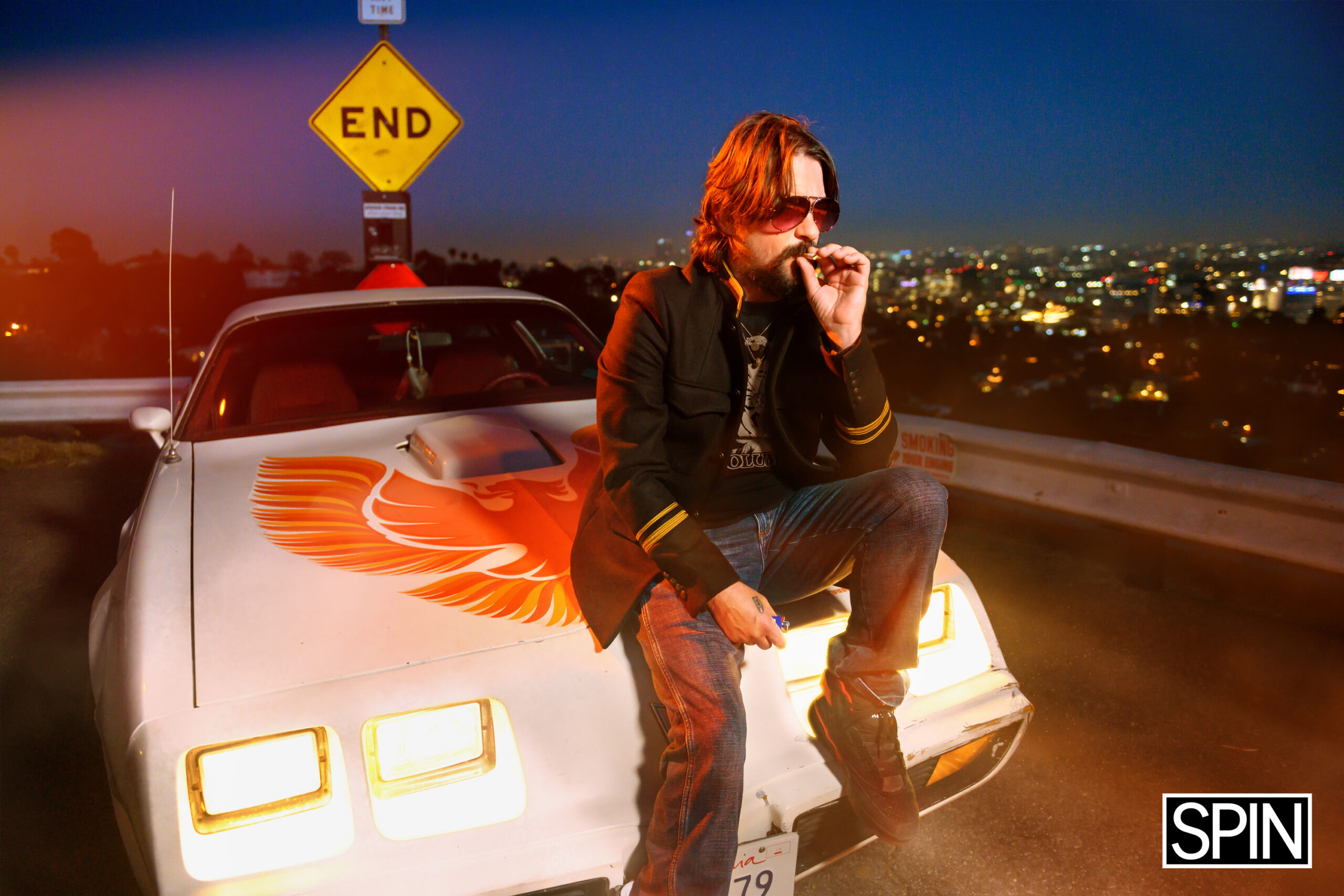

Sitting in his garage recently, with the Hollywood sign in the background, crisp moonlight reflecting off the Hollywood Reservoir below, Shooter Jennings is as relaxed as anyone can be while stuck in quarantine. In a skeleton T-shirt, black pants and Death Row Records special edition Patrick Ewing sneakers, he leans on the trunk of his 1979 Pontiac Trans-Am, sipping a Solo cup full of Mello Yello and Tito’s Vodka. Tattoos, including of a pistol on his inner left forearm, adorn his arms.

Dusty and dotted with his kids’ toys like L.O.L. Surprise and a mechanical Escalade, the garage is fully equipped with a Street Fighter 2 arcade game and a wall of vintage Apple IIe and classic Macintosh computers, adjacent to several shelves of swag from his BCR record label.

If you catch him at the right moment, he can rattle off stories about everyone from John Carter Cash to Bob Dylan without blinking.

“You’ll never hear anyone talk bad about Shooter,” Brandi Carlile says admiringly. “He can get along with everyone, and even if you find a problem with someone, Shooter will always have something good to say about them. That’s rare.”

His parents were touring machines, and summers were frequently spent on a tour bus instead of camp.

“I was in like, fifth grade or sixth grade and I went over to this kid Cliff’s house,” he says. ”When my dad came to pick me up, Cliff said, ‘Hello, Dr. Jennings’ because his dad was a doctor, and he thought that all dads were doctors, you know? I realized my reality was very different.”

He started playing piano on his own at 18 months old, picked up drums when he was five and began programming them at seven. Jennings soon became enthralled by synthesized sounds, especially those of Nine Inch Nails, first hearing Trent Reznor’s band in eighth grade when a friend insisted he pick up the 1992 Broken EP.

“It was the coolest, most aggressive music I've ever heard,” he says.

Shooter played his parents Nine Inch Nails’ The Downward Spiral — but knew there would be issues.

“I knew I had to like explain away the anti-God shit to my mom, and the cussin’ and the suicide shit,” he says. “But we connected over music. We’d share the music we liked with each other.” Shooter said his father “was blown away by it” and realized he was pursuing music that appealed to him. “He saw the computer programming, and he thought it was cool.”

Waylon respected Reznor’s musical prowess — but not his lyrics.

“‘My son loves Nine Inch Nails,” Shooter recalls his father saying in an interview in the mid-’90s. “‘I think Trent Reznor is a musical genius and a lyrical idiot.’ My mom told me it sounded like suicide anthems and bowling balls hitting trash cans.”

“He’s right, I said that,” Colter says. “I couldn’t understand it. But once I saw Reznor at Woodstock [’94] and saw what he was doing by holding the rhythm, it was brilliant, because I understood that. Then I thought it was OK.”

Also at this time, Shooter got into the showmanship of Use Your Illusion-era Guns N’ Roses and the provocative shock rock/industrial metal of Marilyn Manson. In the late ‘90s, Manson was one of the most polarizing musicians in the world.

“I thought it was the devil,” Colter says, succinctly expressing one pole.

Waylon bought a mixing board and put it in their pool house — “the smartest thing he could have done to keep Shooter interested in music and tell him what to listen for,” Colter says. Soon after, father and son recorded an album together called Fenixon, which featured industrial reinterpretations of Waylon’s hits.

Thanks to Metallica’s James Hetfield — a longtime fan of his — Waylon and the Cows were invited to play three dates on the Lollapalooza ‘96 tour, bringing Fenixon to a wider audience than ever intended. Shooter, then 17, performed in Waylon’s band at Lollapalooza and sang for the first time in front of a live audience.

“I remember, he kept saying, ‘That’s my boy!’ onstage,” Jennings says. “And I said, ‘DAD, STOP!’ I was singing on stage for the first time in Doc Martens, cargo shorts, a Nine Inch Nails shirt — and playing piano.”

“Battle of the Bands at my high school was after this,” Shooter adds with a chuckle, as he fires up a Marlboro Red.

As a kid, Shooter traveled with his parents to Los Angeles when his father made film and TV appearances. They’d stay at the posh Beverly Wilshire, and the young Shooter was fascinated by Hollywood. He still has a thing for the movies of his childhood.

“At a very young age, the Muppet Movie would have a big effect on me. And that movie made me fall in love with Hollywood,” he says.

He graduated high school in 1997 and spent the next couple of years playing with his band Stargunn, which he started with a couple of pals. With their heavy riffs, big drums and rock influences, the band wasn’t a fit for Nashville, at a time when country-pop dominated the airwaves there. They honed their blend of Southern and hard rock within the confines of Music City and recorded an EP at Jennings’ pool studio.

After a few years of mulling things over and writing, Shooter told Waylon that instead of going to college, he wanted to buy a Pro Tools rig and give music a shot.

By 1999, Stargunn had a string of shows at the Whisky-a-Go-Go in Los Angeles. On night two, a curious young music executive named Sean Ricigliano showed up with his childhood friend, Vince Vaughn, who brought along Dwight Yoakam, who wanted to hang with Waylon. Colter was at the show to support her son as well. There were 15 other people in attendance.

“The band was über raw,” Ricigliano remembers. “They did a killer rock version of ‘Ramblin’ Man.’ That was the moment that shined through, and I could see what he was trying to pull off, and you could see glimmers.”

Shooter returned to Nashville, but sent songs to Ricigliano almost every day. Each was better than the last. Eventually, Ricigliano and his partner traveled to Nashville to persuade Stargunn to move to L.A.

“He was like this little rock version of Prince because he could play every instrument and program drums. He was just so crazy accomplished at computers too,” Ricigliano says.

Shooter thought back to the Muppet Movie. He knew if he stuck around in Nashville, he’d be hard-pressed to escape the “Waylon’s boy” label, so he told his dad he wanted to move.

“He was totally fine,” Shooter recalls. “He wanted to move to Arizona anyway.”

Waylon and Jessi sold their house and left Nashville. On May 27, 2000, Shooter Jennings and a couple of his Stargunn bandmates packed into his 1995 Toyota Camry and left, too. Four days later, they were in Hollywood. “We went there to party, play shows and get a record deal,” Jennings recalls.

By early 2000, the landscape of rock had shifted. New York City — with a burgeoning pre-9/11 scene that consisted of Jonathan Fire*Eater, the Mooney Suzuki and the Strokes — and Detroit, home of the White Stripes, were emerging. L.A.’s two-decade run as rock’s epicenter was done.

Stargunn didn’t notice. They gigged and toured relentlessly, eventually selling out clubs on the Sunset Strip. Ricigliano introduced them to Rage Against the Machine's Tom Morello, his longtime friend.

“I was absolutely blown away,” Morello says. “They were everything I love in a rock band. They had really great songs, a tremendously charismatic frontman in Shooter. It was almost in some ways like a badass boy band with one skater dude, one really cute dude, there was a Frenchman who played left-handed guitar. Shooter was the ringmaster of this thing, and their songs were really fucking great! I wanted to help because 1.) Shooter is a really great human being and 2.) It’s a great band that I thought could be the biggest band in the world if the chips fell the right way. It was what Use Your Illusion should have been, and I say that as a fan of Guns N’ Roses.”

Morello helped the group ink a demo deal with Rage’s label, Epic, and produced a Stargunn album. Jennings became close with Morello and his wife, who hosted the band for meals and occasional holidays.

“He was a badass, with a bad boy kind of vibe, but he was the sweetest, kindest soul that you can hang out with all the time,” Morello says. “He was a puppy dog kind of rock star. That’s an unusual characteristic for the Hollywood, street-urchin kind of vibe he was going for.”

Stargunn had started infighting, and the album Morello produced was never released. But opportunities kept coming for Shooter.

Following Rage’s breakup in 2000, and while Morello's new band Audioslave was recording, the guitarist started performing folk songs as the Nightwatchman at open mics across the city. He asked his young friend to record some demos.

“He could put down on tape my entire catalog of songs, which was a huge boost to me as a fledgling folk troubadour,” Morello says of those 2002 sessions.

Duff McKagan was in L.A. to play some shows with his band Loaded when he first heard about Stargunn.

“I remember them bringing out a white piano and he played a ‘November Rain’-type song. I wasn’t out scouting or anything, but I could just tell that Shooter was the guy,” McKagan said. “I didn’t know he was Waylon’s kid or anything like that. We became friends from there.”

That almost led Jennings to a shot at fronting Velvet Revolver.

Stargunn opened for what was to be an impromptu Guns N’ Roses reunion at the Key Club in West Hollywood without Axl Rose — McKagan, Slash and Matt Sorum played together with Dave Kushner on rhythm guitar. Jennings hopped on stage for three songs. It was one of the highlights of his career, but he didn’t realize how much they liked playing with him, too.

“After that, I got a weird email from someone I didn’t know who asked if I’d be interested in jamming with those guys,” Jennings says. “But this thing happened where they asked me and I was like, 'Well, I got a band.' Like, I wasn't trying to say no; I was just trying to be transparent.”

He eventually realized he may have lost a huge opportunity.

“Years later, Matt Sorum was like, ‘You said you wanted to have your band!’” he says with a shrug. “Like he made fun of me about it. So I was like, ‘Oh, it was real.’”

In 2002, things started to fall apart. Shooter’s father went to take a nap and never woke up: Waylon Jennings died from diabetes complications in February of that year.

“I remember the morning that he died. They called my phone and I had been out all night at the Standard hammered, and I didn't answer,” he says. “He or my mom called at that point in time that morning — I didn't have any kind of premonition, but I remember it. I didn't answer ‘cause I was too hungover. Two hours later, he died.”

Then the years of turmoil took their toll, and Stargunn broke up. Shooter’s pursuit of rock stardom stopped. Instead, he looked inward. He studied his father’s music, started to listen to Hank Williams Jr. and decided to perform as a singer-songwriter.

“I just got it for the first time,” he says.

Jennings hunkered down in Paramount Studios in Hollywood to record new material in 2003 and 2004. He was introduced to a new, ambitious producer from Atlanta. By the time Jennings completed his first album in this new direction, Dave Cobb had become one of his closest musical confidants.

“We hit it off immediately,” Cobb says. “We bonded over Ministry, Skinny Puppy and Nine Inch Nails, and went to make a country record somehow. Both of our paths changed after that first record.”

Put the "O" Back in Country was a success, showcasing Jennings’ prowess as a solo artist and songwriter. With “4th of July,” he was seen as a rising star — the album peaked at No. 22 on the Billboard Country charts, though it landed at No. 124 on the Billboard 200.

“I love Shooter as a kinder, gentler Axl Rose,” Morello says of 'O.' “But this felt like he was continuing his family legacy in a very authentic way.”

Cobb and Jennings would go on to collaborate on three more albums, including 2006’s psychedelic-leaning Electric Rodeo and 2007’s Nashville-inspired The Wolf. Yet Jennings continued to battle his self-doubt.

“I’m not by any means, like, shitting on fans, because I've had some wonderful people, but I didn't know why they were there for me,” he says. “I never knew for real."

And the music he was putting out wasn’t a proper representation of the kid who grew up listening to Reznor. Following 'O,' each album sold less than its predecessor. The crowds were dwindling, and soon, the money dried up. After years of embracing his country roots, he tried to blow it all up with Black Ribbons.

And he did just that.

“It was an amalgamation of the music we grew up listening to,” Cobb says in defense of Black Ribbons. “We weren’t planning to make anyone else happy.”

Jennings was determined not to pander to an audience that may not have fully understood him. But he didn’t gain a new audience in the process.

"Black Ribbons is a brilliant, ambitious piece of art that never got the break it deserved. Rock audiences missed out; they wouldn't give it a chance because they saw Shooter as a country artist,” says Michael Moses, his publicist at the time. “And country audiences were busy listening to Blake Shelton and Lady Antebellum; they couldn't understand why Waylon's boy had made this weird rock record narrated by Stephen King. With neither side 'claiming' it as their own, the album fell into music purgatory. The record label didn't know what to do with it and was really too small to give it a big push. It was so unfair to Shooter, who, like all great artists, bravely stepped outside his comfort zone to express himself in a new way. On that personal level, the album was a huge success. But it would've been nice to see him rewarded for his genius."

Making matters worse, Jennings made some unconventional decisions to promote the album — including an appearance on conspiracy theorist Alex Jones’ InfoWars. He doesn’t consider himself a political person, but to some, showing up on the show seemed like an endorsement of Jones.

“He played the whole record, and I was on there for four hours,” Jennings says, “because he was the only guy that would promote the record. I would listen to him a little back then, but I always felt he was a little bombastic — like an extremely over-the-top Art Bell. At the time when we did that record, everyone thought I was fucking crazy.”

Then came the night in Houston — and the realization that he might need to get a regular job. At least he had a SiriusXM show, called, like his album, Electric Rodeo.

“But it doesn’t pay a ton,” he says quietly. “I was looking at like, working at a fucking computer store or video game store… There were many times where I was like, ‘I don't know what to do,’ you know? Just because I couldn't make enough money to play music and live here [in Los Angeles].

“It was definitely traumatizing. But in retrospect, that record has given back to me more than anything. This was the first time I didn’t feel like I was born on third base, and deflated the audience that was there for the wrong reasons.”

I first met Shooter Jennings through his former manager, Jon Hensley, a friend of mine. A native of Bowling Green, Kentucky, Hensley had the perfect demeanor to manage artists. Tall, and almost always wearing sunglasses, cowboy boots, a half-unbuttoned shirt and dark pants, Hensley was kind-hearted but not afraid to mix it up for those he cared about.

He had already rejuvenated Wanda Jackson’s career by introducing the Rockabilly Queen to Jack White in 2010. He knew he could help Jennings.

Jennings left Los Angeles temporarily for New York City in 2011 with his longtime girlfriend, Sopranos star Drea de Matteo, and their two young children. By 2013, Jennings was in a better place. He reconnected with an old friend from the Stargunn days, Misty Swain. A friendship was instantly rekindled and a romance sparked — they moved in together and married six months later.

Sitting at a burger restaurant in Hollywood in 2013, Hensley, in his reserved Kentucky drawl, complained for a second that Shooter hadn’t given him a heads-up about the marriage. Then he told me how he planned to get Jennings’ career going.

“I’ve got this plan,” Hensley said at the time in between bites of a burger. “Shooter is going to get into production on top of his own career, and just watch — he’s going to be one of the best producers in music.”

At that point, Jennings wasn’t a producer: He had done production on his own albums, 2012’s The Family Man and the then-soon-to-be-released The Other Life, but that was really it.

“He was the first person to really connect with me on this level that had nothing to do with my dad or Nashville or anything,” Jennings says. “I never felt entitled, and I was usually more hypersensitive to how other people viewed me versus anything else. But Jon would check me.”

By the end of 2013, Hensley and Jennings formed Black Country Rock Records, a way for Jennings to better establish his own identity, pursue outside-the-box projects and make music without restriction. Jennings took on more producing projects. He’d produced Jason Boland, Hellbound Glory (which was never released) and Fifth on the Floor before he started working with Hensley, who immediately enlisted him to remix and perform on Wanda Jackson’s version “In the Cold, Cold Night” that was on a Jack White tribute album.

A turning point came when Jennings worked with country singer Julie Roberts. As the sessions wore on, Jennings felt them both flourishing. “As a producer, it's like, I see my work paying off with her good work,” he explains.

Though it was never released, that album boosted his confidence. Meanwhile, Hensley found ways for Shooter to make money again. He would play shows with the Waylors, his father’s old backing band. They would perform first before joining Jennings for the main set. Hensley encouraged belt-tightening, and money started coming in.

The two hung out at WrestleMania, talked on the phone until the wee hours, played video games and got in friendly drunken arguments. They became best friends.

They saw each other for the last time on a trip to Dollywood. In June 2015, Hensley died suddenly at age 31.

“He had so much to offer,” Jennings says. “Jon Hensley would have changed so much, you know, and I felt that then he was just such an anomaly of a person and fearless.”

Jennings took time to mourn. Then, at Misty’s urging, he tapped Adam Barnes to be his new manager to “keep doing what Jon was doing.” Barnes, the grandson of Waylon’s old bassist, Jerry “Jigger” Bridges, had been the Waylors’ tour manager and became close with Hensley and Jennings. He understood the big vision.

“Jon brought him to another level of touring and he knew Shooter wanted to produce records, so that was something we attacked,” Barnes says.

Following the release of a traditional George Jones-inspired EP, Jennings unleashed the direction that he and Hensley envisioned. In 2016, Jennings released Countach (For Giorgio), a Giorgio Moroder full-length tribute album.

Countach earned his best reviews in years. The Guardian called it “a potent, muscular celebration” while Consequence of Sound enthused that it could “easily get messy, but because the album’s collage-style approach gets established early on, it all feels part of one singularly distant transmission.”

The record also featured a few notable guests, including Carlile and Manson.

Jennings met Carlile in 2012 at a Johnny Cash tribute show in Austin. He noticed her NeverEnding Story tattoos and the two instantly bonded over ‘80s movies. He enlisted her for the track “The NeverEnding Story.”

“The ‘80s get so white-washed in roots music,” she says, “because we still sing about the Dust Bowl and train-hopping like it’s a thing that we do. He was like ‘Fuck that, we all played the same video games and all wore Hammer pants. Why can’t we sing about our actual childhood and what actually raised us and still be country and roots?’ Countach was the first thing of his I’d ever heard he’d done, and it was the really innocent beginnings of a really honest friendship.”

After Countach, Carlile insisted that Jennings be involved in her next project.

“She just out of the blue said she wanted me to be involved,” he says. “And then a day later, I got a text from her said, ‘Do you know Dave Cobb?’ And I was like, ‘Yeah, of course.”

“I was recording my song ‘The Story’ for Dolly Parton to sing [for the Carlile tribute album Cover Stories],” Carlile recalls. “I felt like I came up against the wall because I didn’t know how to lay down a Dolly track. I heard about Dave Cobb and got his number and asked him to do a middle-of-the-night session for this song. He dropped everything and did this session with me. I felt the same way I did with Shooter as I did with Dave, except I knew he was a producer. He made me happy — and nervous — too. I knew I could work with this Dave Cobb guy, but I really need Shooter there. [Laughs.] So I asked him if he knew Shooter Jennings…”

“She called about it and I said: ‘Are you kidding me? The guy is like my brother!’” Cobb says.

“All I knew was when I was in a room with him, it made me happy,” Carlile says. “It made me inspired, made me laugh and made me talk about important things. I knew somehow I had to get him in the room while I was making the album. I didn’t even know he was a producer.”

The album they made together, By the Way, I Forgive You, landed six Grammy nominations. But Jennings, who had already missed so much, missed out on his first Grammy win.

At least this time he had a great reason.

There were two ceremonies that day: one for the non-televised Grammys that are important to the Americana/folk diehards, and the other for the mainstream acts — the one that is televised live.

The first ceremony, where Carlile, Cobb and Jennings were nominated for six awards, was held in the early afternoon but conflicted with the rehearsal for the televised ceremony.

“We had to choose between abandoning the roots community to do this rehearsal, or we lose our first mainstream opportunity,” Carlile says. “We chose Americana, and Shooter was like, ‘I’m gonna make a sacrifice.”

While Jennings was onstage rehearsing with the Grammy house band, he received a text that Carlile had won…and won…and won. So had he.

Around the same time, Jennings heard from his old friend McKagan.

Following the massive success of Guns N’ Roses’ Not in This Lifetime reunion tour, which had started in 2016, McKagan decided to take a step back. He had written an album, and a friend from Elektra Records recommended that Jennings produce it.

“Shooter! That’s fucking perfect!” McKagan remembers thinking.

They worked on the songs together over what McKagan calls “a serious hang time.”

“In the studio, he’s a different kind of animal. He’s focused and got a way about him,” McKagan says. “He nurses a tallboy all day long. It’s the same beer over nine to 10 hours. The same fucking beer! He’d pace, and I’d love it when he’d smoke a little bit of weed because he’d come up with some keyboard that he maybe wouldn’t have thought of. He just let me be me.”

When Tenderness was released in 2019, McKagan enlisted Jennings as the bandleader for the follow-up tour.

“He’s just a marvelous man and a good motherfucker," McKagan says.

Next, he worked with Tanya Tucker, who remembered him from his days in Nashville. “I’m the only woman Waylon called ‘hoss,’” she says, noting that Shooter “went to the same tutor as my kids.”

Jennings and Carlile teamed up to co-produce Tucker’s first album in nearly 20 years — but it almost didn’t happen. On Christmas Eve 2018, 11 days before she was set to begin recording in Los Angeles, Tucker called Shooter, saying she had doubts about the record. He convinced her over a night of hanging out (and a few beers).

While I’m Livin' ended up being a critical success. “I’ve never been so glad to have been wrong about something. It was just a special time and I wish I could do it all over again,” Tucker says.

The record won two Grammys, for Best Country Song and Best Country Album. This time, Shooter went up to collect his awards — with Misty and his daughter in attendance.

"I just couldn't believe that that had happened twice,” he says. "I never thought I was ever gonna get a Grammy my entire life. I've pretty much given up on the concept.”

Jennings didn’t go out to dinner and celebrate. “The younger me would have loved to have been out and at those events,” Jennings says, as he sparks another cigarette. “But I had work to do.”

That work? Producing Marilyn Manson’s record.

In 2020, Jennings has produced albums from Jaime Wyatt, American Aquarium, the White Buffalo and the Mastersons. He’s also remixing Margo Price and has an album with Yelawolf on the way. And of course, there's the Manson album.

Earlier this year, American Aquarium, the White Buffalo and Wyatt’s albums were all in the top 25 of the Americana album charts.

"Shooter has a freakishly keen intuition about music and production. He instinctively knew to push me to finish certain songs that I didn’t necessarily intend for this record and now I can’t imagine this album without them,” Wyatt says.

B.J. Barham of American Aquarium agrees. A few weeks before they were set to record their eighth album, a producer bailed and Jennings stepped in.

“He got the demos and texted me two hours later saying he’d love to do it. From the minute we sat down, I knew he had the same vision as I did for the record,” Barham says.

That vision proved to be correct.

Lamentations was the band’s first No. 1 album, topping both Billboard's Top New Artist Album Chart and the Americana/Folk Album Chart.

“I love producing records,” Shooter says. “I used to go into something being, ‘Like, man, what if it’s gonna suck?’ And now, like I go into it and know it's not gonna suck. It just means learning to adapt to different personalities very quickly and pulling the same trick with them all — which is like keeping them calm, keeping them happy, avoiding conflicts and that kind of stuff.”

By now, it’s been six and a half hours since he first filled our cups with Mello Yello and Tito’s. It’s time to wrap up. Moonlight shines down, and there’s not a person or even a coyote around.

For once, Shooter Jennings is surrounded by silence.