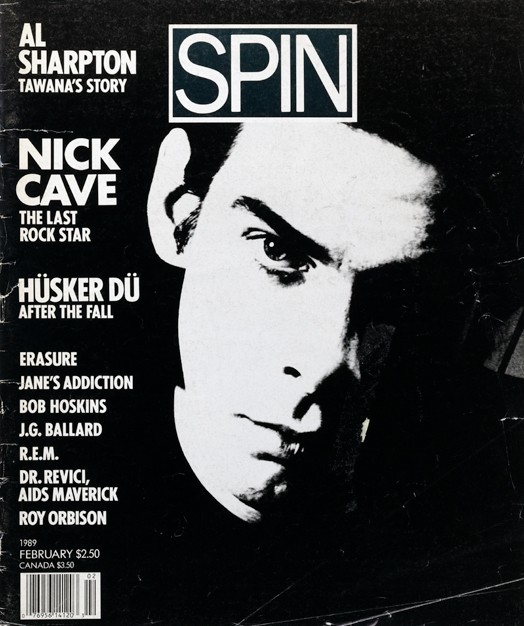

This article originally appeared in the February 1989 issue of SPIN.

Robert Johnson sold his soul to the devil. Went down to a crossroads in the Mississippi delta on a moonlit night and bartered eternity for the devil's own blues. When he died before the age of 21, poisoned by a jealous husband who thought art should imitate life and not the other way around, he stepped into a middle ground between the literal and the figurative, more resonant than either. He became a romantic figure.

A cliché, as Nick Cave has said, is an idea that falls into abuse because it holds too much power. Gaunt, pallid, his jet black hair piled carelessly over his overhanging brow in testimony to some unseen violence, Nick Cave is a cliché every bit as much as Robert Johnson was. As much, for that matter, as Hank Williams—dead at 30 of a frozen heart, a triumph of art over life that is often mistaken for drug abuse—or Charlie Parker, Jim Morrison, Iggy Pop, Lou Reed, or Ian Curtis, who joined the ranks instantaneously when his feet never hit the ground following his one leap of faith.

Nick Cave is the face that launched a thousand second-rate English gloom bands. From his barreling misanthropy in the Birthday Party to the disturbing resignation of his scriptures- and blues-influenced new solo album, Tender Prey, he has lived a decade as a journal of baroque self-destruction that writes itself across the public imagination.

Whether he belongs in the above company in talent remains to be seen. At any rate, that isn't the point, any more than whether Robert Johnson really sold his soul to the devil; he belongs in their company more than in any other. Even before SPIN reported, in its third issue, that he was born with a stillborn twin brother, Nick Cave had emerged, with all the hokum and power it implies, as rock's last romantic figure.

"That story about the stillborn twin isn't true," he says. "I don't know where it came from. I was born with a tail, though." He speaks haltingly, in soft, broken phrases, with neither the arrogance nor the eagerness to please I might have expected.

It has been about a month since he completed a heroin withdrawal program, suggested by the London courts as a favorable alternative to prison after his last arrest. His record company people, with whom he has a long association, are amazed by how cooperative and productive he has been. After years of steady or unsteady work, he is midway through the final editing processes on his novel, And the Ass Saw the Angel, and preparing his band of underground all-stars, the Bad Seeds, for a spring American tour that in the past would have filled most involved with deep dread. "The tail was just a twisted, gristly thing," he says. "It was taken off at birth. That's true."

Nicholas Edward Cave was born, tail and all, 31 years ago in Wangaratta, a one-pub town in the Australian outback. The son of a high school English teacher, he sang without distinction i the Wangaratta choir and harbored boyish fantasies of becoming a criminal. "I was very competitive with my father," he says. "My father worked with the theater. He directed quite a bit. I figured that I worked in a creative field as well, and I knew more about things than he did, and he thought he knew more than I did. I would almost go out of my way to find out about obscure experimental theater that he didn't know about, so I could read it at the dinner table to impress him."

In his book, Deep Blues, Robert Palmer notes that before selling his soul to the devil, Robert Johnson declared his intention to his relatives, and even specified the crossroads to which he was heading. When Johnson then returned to the company of bluesmen Son House and Charlie Patton, whose derision he had fled a year previously, it was with unexpected technical prowess, but also something more. Working the blurry conjunction of fact, myth, and cliché, he sand with very real fresh power: "Early this morning when you knocked upon my door/I said Hello Satan, I believe it's time to go."

It was, beyond everything else, one of the most darkly funny rhymes he'd ever written, bested perhaps only by the one that followed: "Me and the devil was walking side by side/I'm going to beat my woman until I get satisfied." Boorish as autobiography, trite as literature, the rhymes demand some romantic middle ground; finding it, they resonate as richly as any in Western popular music.

https://youtu.be/Ahr4KFl79WI

Nick Cave's biographical particulars fall into a similar middle ground. On "Deanna," his new single, Cave appears as the devil, come to collect the title character's soul. As he told Jack Barron of New Musical Express (twice mediated, this story is perhaps the best way to read Cave), Deanna was a girl he knew when he was about eight.

"'We used to go on this day raids on the different houses around the town…and we used to eat their food, lie on their beds, and steal all sorts of stuff like letters, cutlery, clothes, and money…So one day we robbed a house and found a handgun which we took back to our little grotto. We, I should add, robbed…separately also. One day she was caught by this guy who was in this religious instruction teacher's house. The wife of this teacher thrashed her and the guy did something to her, but I really don't know what it was. The next day I was woken up by my mother and had to answer all these questions from the police. Deanna had gone back to the home and shot the strange man and woman.'"

Cave was finally thrown out of school—the school where both his parents worked—at age twelve, and shipped to a strict, all-male boarding school in Melbourne "to get some God beaten into me." As a boarder, he spent two years beating up the school's day students. When his parents moved to Melbourne, he spent the next years getting beaten up.

"My father died when I was still in Australia," he recalls, "when I was 19. I really enjoyed shocking him, and I'm sure that had a lot to do with why ultimately I failed at art school. I just really enjoyed bringing home paintings of subject matter that I knew would irritate my father. It was puerile behavior, really. I would put pressure on them to encourage me, so they'd have to hang them on the wall in the lounge room."

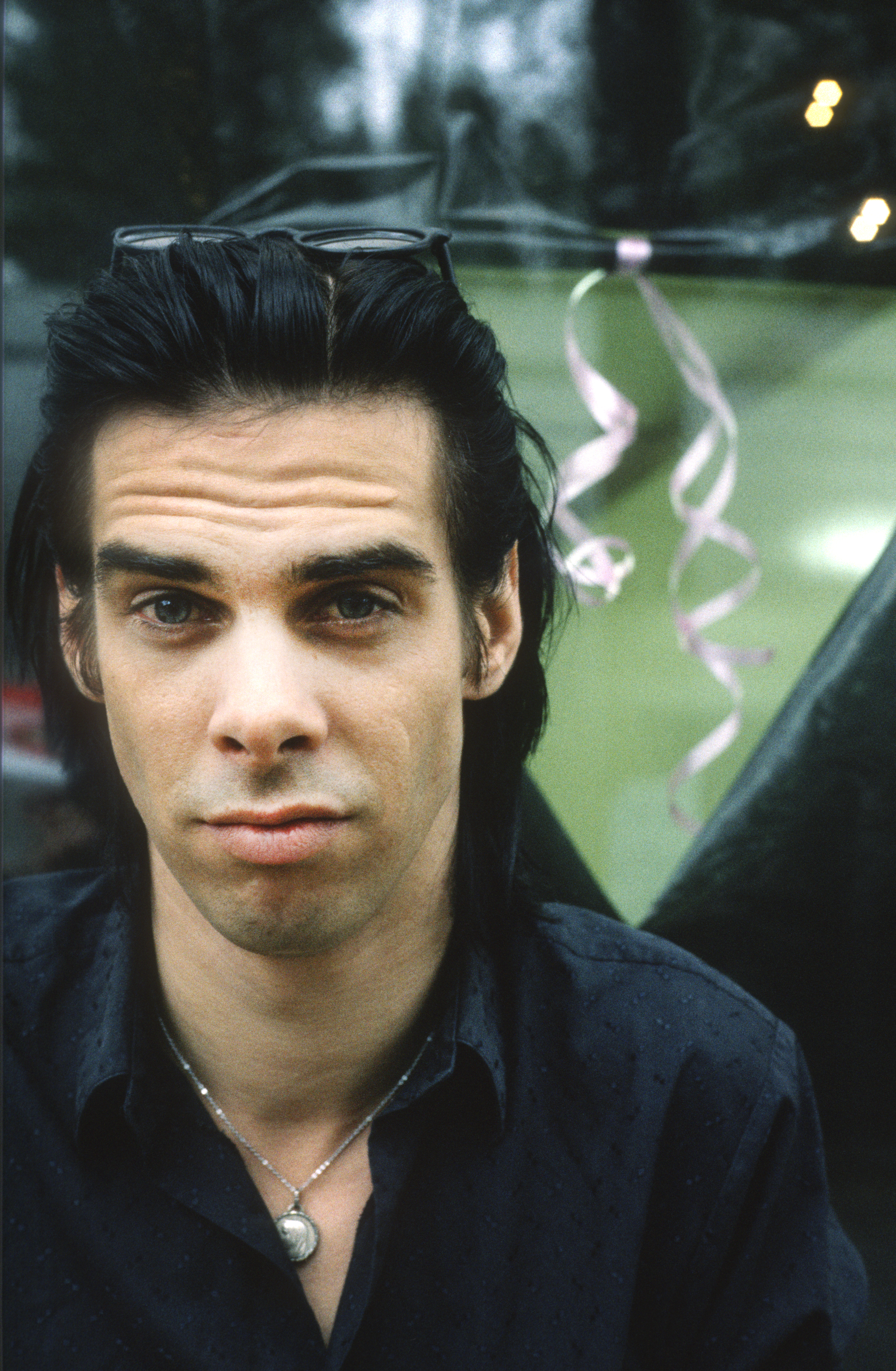

[caption id="attachment_id_345708"]  Gie Knaeps/Getty Images[/caption]

Gie Knaeps/Getty Images[/caption]

"By my last days in art school I was panting very stupid things. I had a couple of feminist art teachers, and I was panting musclemen looking up ballerinas' dresses, in the worst possible way I could. I didn't have much respect for the school by the time I was thrown out. They thought I was just a filthy, stupid, sexist fool. And I thought they had more of a sense of humor than that, but they didn't."

"I also had the band, the Boys Next Door, going at the time, since I was about 14. But the music was very separate. Even then, I never considered music as one of the 'serious' art forms. That's changed for me these days. I wanted to be a Painter with a capital 'P'—that's all I ever wanted to be."

* * *

Last May, Black Spring Press in London published King Ink, a small, expensive collection of Nick Cave's song lyrics, one-act plays, and assorted scraps of prose. Included is an essay entitled "H.M.S. Britain 1982," about the growing number of bands whose existence stood as an homage to Cave and the Birthday Party: goth bands, bat cave bands, depressive young men in whiteface and black haystack hair who played turgid melodramas, magnifying only the obvious elements of the Birthday Party, and only some of those (Birthday Party was one of the last bands of consequence to use swastika iconography).

For a brief time, after their move from Australia, all wide-eyed and hateful, the Birthday Party was one of the most loved and loathed bands in London, something more than a Sex Pistols addendum but less than an equal; they simply showed up too late.

In "H.M.S. Britain 1982," Cave rejects "the honorary title of forefathers to the 'New-Super-Death-Tribe,'" saying his unwanted spawn "REFLECT if anything…'The Mood of the Times' if I may use this sickening expression, i.e. a desire for a bit more violence and so on…and in my most sought after opinion a group that REFLECTS anything other than their own idiosyncratic vision is not worth a pinch and anyway that is enough of that full stop."

https://youtu.be/FxORulyOXs8

"In conclusion, the Birth P. are in essence a slug, nomadic, and their journey is slow and painful and always forward and their trail of slim is their art and so on and they are barely conscious of its issue which bears little resemblance to anything bar ourselves and we make no excuses for that."

According to the music tabloid Sounds, the Birthday Party ultimately dropped the album format because they felt their music was too intense to expect people to listen to for that long.

All clichés, as Nick Cave's career illustrates, are not created equal.

* * *

SPIN: Would you agree that your material so far has been very black-and-white emotionally?

CAVE: Yeah, but I've been that way myself. I have a tendency towards melodrama. I don't know what I can do about that. I enjoy that. I think it's there in most other sorts of music I enjoy. It's there in blues music, it's certainly there in country music. People like Tammy Wynette, for example. Billy Sherrill, who writes her best songs—if he's anything, he's over-romantic about what he writes about, melodramatic to the extreme. That sort of music really affects me. I don't sit there and smirk at it. It affects me right here in the heart. There's a lot of people who weep over what Tammy Wynette does, and they'd consider it an insult to call it kitsch. And I'm one of those people.

How do you consider your voice?

I've always had a lot of problems with my voice, so I've based a lot of singing on what I do best, which is basically express myself, and put character in it. But in the meantime, my voice has grown quite good in a sense, and I haven't used it in that way. I've been singing the wrong types of songs for my voice. I would like to try some things that are more challenging but still very simple.

Alan Vega of Suicide once said the thought that Iggy should be singing cabaret songs, jumping into a late-period Elvis model. It seems like the next step for you.

That idea is quite attractive. I would like to sing to that kind of instrumentation, and sing those types of songs. But at the same time I very much want to sing my own material. I'm tending to write much more classic, simple songs these days, and not be so concerned with showing off my word power. It's never been easy for me to write a simple song that isn't clever or whatever, and I would really like to be able to do that. I hope the next record I make will be more like that—a record of classic type songs—if possible.

But I don't like that word cabaret. It's got a camp element to it that worries me quite a lot. I don't want to become a parody of someone else; I don't mind being a parody of myself. I don't want to become a second-rate Tom Jones or something. He's one of my favorite singers. But I've watched a lot of talent shows in my days, where you have these Elvis impersonators, and some of them are really remarkable. But who wants to do that? I'd be quite happy to be able to evoke in the hearts of my audience the kind of emotions he evokes in the hearts of his. But not at the expense of my music.

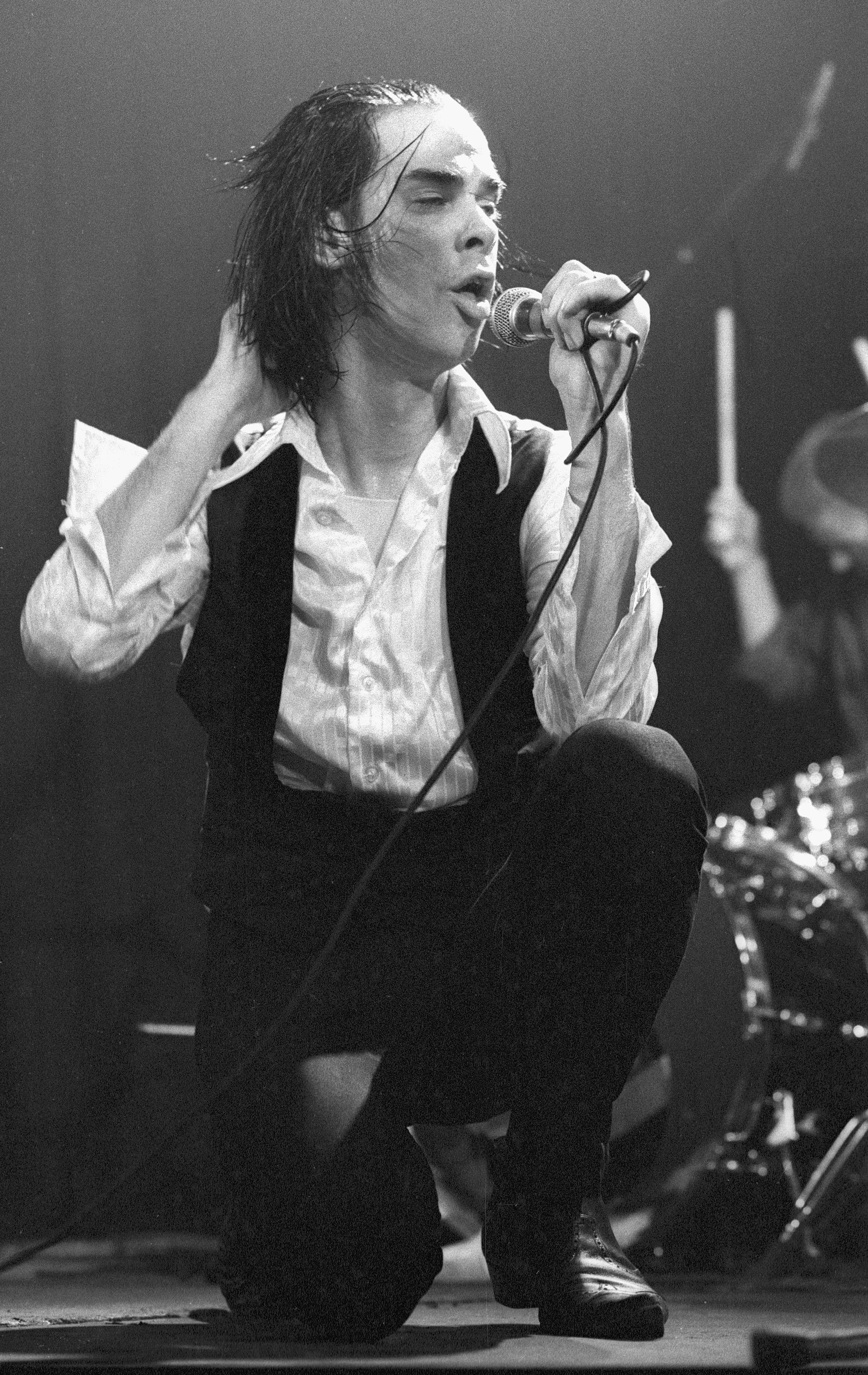

[caption id="attachment_id_345711"]  Frans Schellekens/Redferns via Getty Images[/caption]

Frans Schellekens/Redferns via Getty Images[/caption]

Is it a mistake to identify you with your characters?

The characters are all autobiographical in a sense. I tend to prefer to use a character as a vehicle for saying something about myself to actually talking about myself in the first person.

Though the process of writing And the Ass Saw the Angel over the last three years or so—the book's very much about obsessions, and my obsessions grew as I became more involved in the actual writing of it. There was a definite parallel between what was going on with me, even though I was living in Berlin, a city, and what was going on within the central character, this mute boy who lives alone in the backwoods, is chastised by everyone, and obsessed about things, all seen through a paranoid's eyes. In a way, the book is an exploration of those particular obsessions. But the point is that it's very much removed from me in any superficial sense. The last thing I want it to be seen as is a kind of rock'n'roll diary.

Are you self-destructive?

I guess. Fuck, I don't know. These aren't things you sit around thinking about. If people need to believe certain things about me, I don't mind. I've often been accused of this, and I think it's quite wrong, but I'm not trying to sell myself in that particular way. I just feel comfortable about writing about certain themes.

Did you ever worry that if you straightened up you'd lose your edge?

I don't know about losing my edge, but I was often worried that I wouldn't be able to write anymore, or perform. I basically used drugs for those reasons, or I told myself that was why I was using them. So far, that's not true. I'm getting a lot more done these days, and can remember doing it, which is refreshing. I feel much better about everything I do now, because I know that I'm doing it myself, at least. It's much more difficult this way.

But the thing that struck me was that because people saw me that way, they assumed that I was happy to be that way, that that's the way I wanted to be, or that's the way I was selling myself. It goes far beyond that. It's something that I at the time had absolutely no control over. It was just a fact in my life, there was nothing I could do about it.

* * *

On Christmas Eve, 1954, John Marshall Alexander, Jr., a charismatic rhythm and blues performer who recorded with some success as Johnny Ace, became momentarily the world's greatest singer when he learned, with the aid of a revolver, to project from the mouth backward. It was a swift act, not more than a couple milliseconds plus cleanup time, but it made him a legend, his shadow stretching even beyond Hank Williams' more eagerly anticipated pre-show curtain call of one week later. A nation wept and accorded him a major hit record. He was No. 1 with a bullet. Then romance and greatness dropped their flirty ways, leaving Johnny Ace to become a macabre footnote to history.

In the years after Robert Johnson returned to Son House and Charlie Patton, there's no telling how many inconsequential bluesmen sold their souls to the devil, only to become inconsequential bluesmen with bleak prospects for the future; figure it was a period of crossroads gridlock, of heavy trading on the devil's big board, and not everybody got what he was paying for: the metaphor made flesh, the cultural made natural.

https://youtu.be/oSl4KX7zBTQ

Never mind that Robert Johnson was a poor black man living in the rural South; never mind that he was probably a great talent, a master of word and music, an inventor whose imagination turned to dark elements already in the air: the way he played and sang proved that he'd made a pact with the devil. Once the cultural (Johnson's art) became natural (his pact), Johnson slipped into myth. The romance of art as a projection of inner self-destruction proved too strong. People, it should be noted, like to believe.

Nick Cave's deal with the devil, orchestrated on different metaphorical terms, serves the same purpose: it collapses the gap between public and private selves. Singers like Bruce Springsteen, Bono, and John Mellencamp project themselves as big screen versions of their romanticized audience; it would be difficult to model one's behavior on Springsteen's, because he doesn't have any.

As a role model, vicarious or otherwise, Nick Cave is all behavior, behavior as art. Like Hank Williams, Lou Reed, or Jim Morrison, he annihilates himself to become art. The proper response to Springsteen, even for a fan, is contempt, because Springsteen embodies the terminal status, the absence of possibility, that we all need to escape. The proper response to Cave, even for an impartial observer, is just do it. As longtime collaborator Lydia Lunch says, "What's he gonna do next, explode? Fine. Id' pay to see it. Isn't that what they charge for at the door?"

"The initial feeling behind the Birthday Party," Cave says, "was one of disgust and disrespect for the English audience and English people and England, full stop. I think the Birthday Party was something quite separate from what I do now with the Bad Seeds."

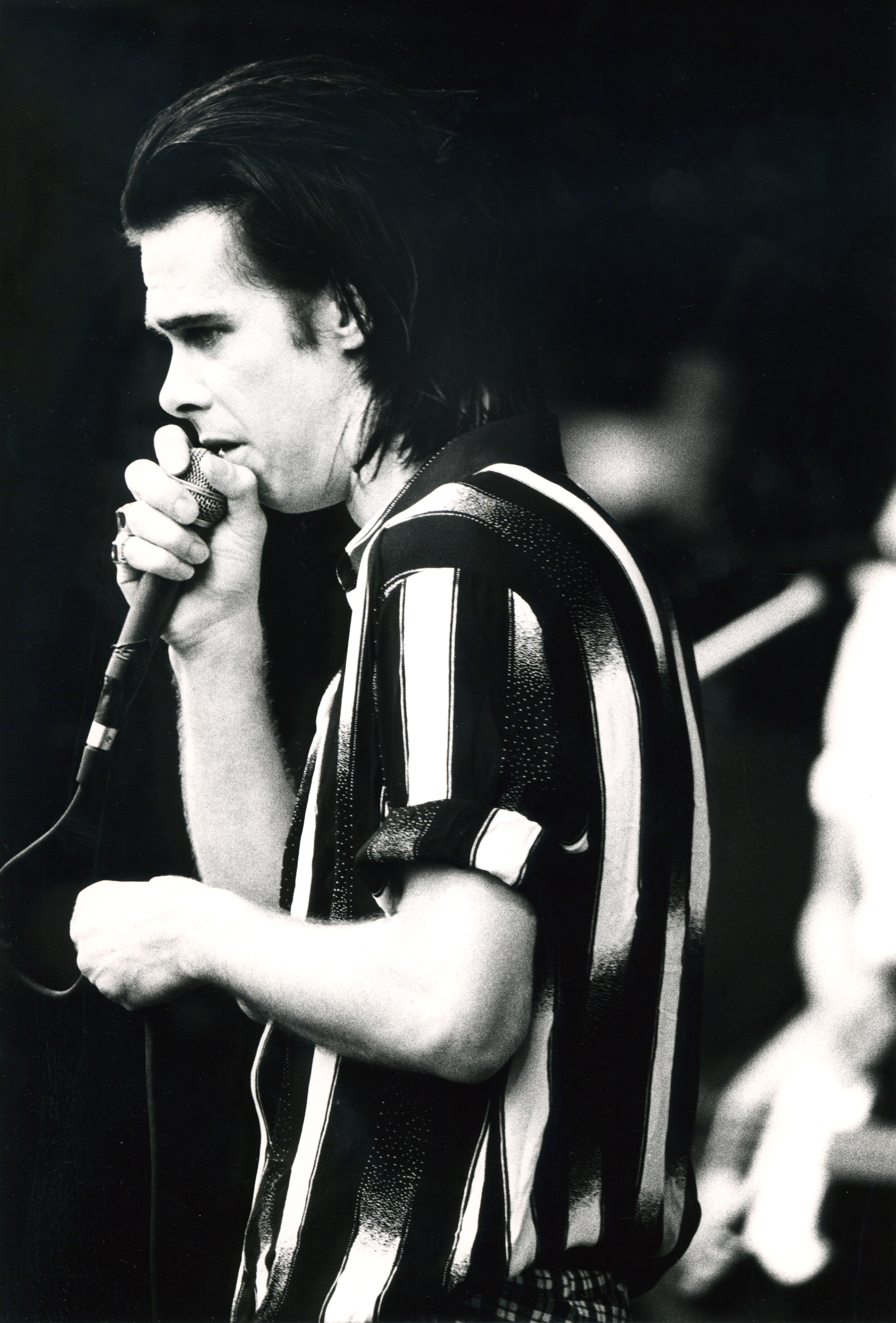

[caption id="attachment_id_345715"]  Gie Knaeps/Getty Images[/caption]

Gie Knaeps/Getty Images[/caption]

Cave's work with the Bad Seeds (currently including Blixa Bargeld from Einsturzende Neubauten, Kid Congo Powers from the Gun Club, and Mick Harvey from the Birthday Party), has been both bleak and increasingly accessible, a long slog toward rapprochement with the similarity biblical despair of Leonard Cohen. (On hearing Cave's 1984 version of Cohen's "Apocalypse," Cohen said, "I thought his instincts were impeccable for taking that song and tearing it apart.") His rumbling bullfrog voice has become a more pliant rumble, and his obsessions have come into sharper focus.

In the last two years, even before he began his recovery from heroin addiction, he has co-written and acted in a film (Ghost of the Civil Dead, a grisly prison movie in which he plays a violent psychopath), completed his novel, and performed with the Bad Seeds in his friend Wim Wenders' Wings of Desire. Another project with Wenders is in the works. At 31, Cave is learning to create theater outside his own myth—a myth he, like Johnny Ace, says he never wanted.

"There's not very much romance in it for me. From my side of the fence, it's not that attractive, really. Any kind of romantic notion was lost many years ago. For me there whole thing's just very ugly. I haven't seen Bird yet, but I don't think they would have made the movie if he wasn't a great jazz musician. I don't thin that's the reason Charlie Parker's remembered today. I hope not anyway."

"I feel more in control of my life to a certain degree, but I'm also aware that it's very easy for the whole thing to spin around again. I by no means can sit back and relax and think that phase of my life is over."

* * *

My favorite piece from King Ink is the one-act collaboration with Lydia Lunch, "Gun Play #3," which runs, in its entirely as follows:

"Gaudy colored lights flood the stage on which a young man spins a blindfolded female partner around in the background [loud]. She stumbles, squeals w/laughter, stumbles [oh how silly] a bit more and then mouth open and still giggling [arms outstretched] she makes a gay little bee-line toward the young man. When at arms' reach [Is that you, Tommy, giggle] the man jams a Colt 45 into her mouth and blows off the back of her head. The Big O sings 'Pretty Woman'…oh."

BLACKOUT

I hope that makes things clearer.