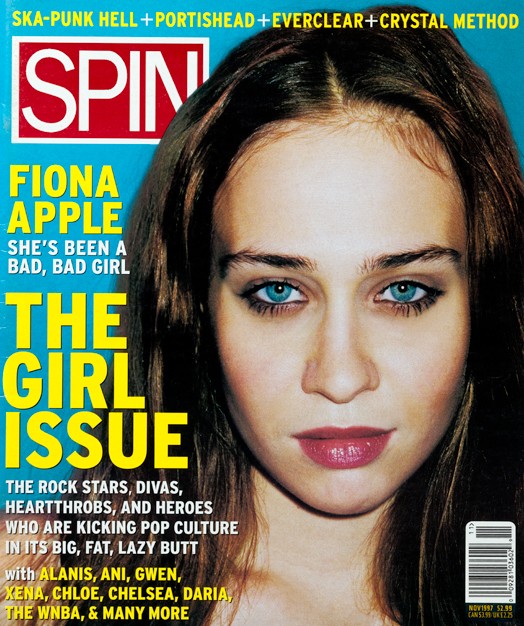

This article originally appeared in the November 1997 issue of SPIN.

Pop stars are different from you and me. They figure out early on that the most interesting person they know is themselves. All teenagers are natural pop stars, and so are most Americans, especially if they grew up being promised a dollop of fame in exchange for their misery. Fiona Apple is a pop star trapped in the body of a pretty teenage girl.

It's August in Atlanta, and Apple is backstage at the Lakewood Amphitheater, coming down from her last gig on the Lilith Fair tour. She emerges from her dressing room to walk through something called a meet and greet, which is where strangers line up with disposable cameras and take pictures of you. "Now I have to be nice," she says, putting on her Gucci sunglasses and wrapping a scarf around her head like she's Anouk Aimee in Fellini's 8 1/2.

Earlier, onstage, she was more like Liv Tyler with an inner Janis Joplin struggling to make itself heard. Just over a year after the release of her debut album, Tidal, Apple has learned to become a true rock diva. Last year she was in singer/songwriter mode, anchored to her piano, as sensitive as Joni Mitchell was in her Blue period. Now she takes the stage flinging her arms, tossing her long hair, stomping her feet, and generally acting like a sexy, temperamental teenager, the kind of arty, ravished girl you knew in junior high who wrote poems in all lower-case letters. There's an element of fierce playfulness in her performance that doesn't often show up in her interviews, or her photographs—where she mostly looks unhappy. "If you want to see me cry, come to a photo shoot," she says. "They treat me like I'm a hotel room; They make a mess, and then they just leave it."

At the meet and greet, she's still in her stage clothes, which are both sexy and girlish (assuming there's a difference between sexy and girlish, which is something Apple forces you to consider): tight black stretch bell-bottoms, a black bra under a lace top, black pony boots, and a backstage pass hung from her navel ring. She's tougher looking than in her videos, where what comes across is vulnerability and an almost painful lack of guile. She's shaking hands and autographing CDs, keeping a wary eye on me, the guy in the corner with the pad and pen. Suddenly she walks up and says, "Are people ever mean to you?" She takes off her scarf and she's got hair horns, twin bunches gathered in antennae points at either side of her head. I feel monitored. She later tells me that she likes to act all freaky and possessed around reporters, so they won't ask the same dumb questions, like "How does such a big voice come out of such a tiny girl?" and "I heard you were raped, what was that like?"

Then she's off. If this were the 19th century, she'd be a character in a novel by Henry James about an enigmatic American girl: Is she innocent or guilty, young or old, helpless or controlling? But it's 1997, not 1987. Fiona Apple is a rock star, and before she has fully become a person, she has become a persona. It's taking her some time to decide which part of her is the image, and which part is real.

In retrospect, Apple's fame seems inevitable. The child of performers, she was raised in New York and Los Angeles, the two hubs of celebrity culture. Her father was a TV actor, her mom a dancer and singer. Her grandfather played saxophone with the Harry James Orchestra and sang from the roof of New York's Astor Hotel in 1942: "Give me one dozen roses /Tuck my heart in beside them / And send them to the one I love."

At the urging of her parents, Apple started psychotherapy when she was 12, and learned young how to talk about her feelings. "I've spent my whole life telling my innermost secrets to strangers," she says. She also kept journals, in which she wrote the lyrics for "Never Is A Promise," when she was 15, while trapped in a motel room with her parents. That was the song that hooked her manager, Andy Slater, when he heard the three-song demo tape that he would later help turn into Tidal.

"She had never played with other musicians when we started cutting the album," says Slater, who also manages the Wallflowers and co-produced their platinum-selling Bringing Down the House. "She didn't have all the songs written, and for a long time it was just me trying to find out what kind of sound she liked—Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holliday, and the hip-hop records. So we started from there."

At the time, she was 18 years old, her dad lived in Venice Beach, and she was hanging around L.A. Apple just missed getting her high-school diploma, she claims, because she didn't pass Drivers' Ed. "A voice told me to go to Los Angeles and make that demo tape," she says now. The voice had good timing. Tidal was released in the breakout era of women in rock. Jewel and Joan Osborne held MTV by the throat that summer, and according to the media, women were the new Seattle. By the time she joined the Lilith Fair, Apple had already been touring for a year in Europe and the U.S., had opened for Chris Isaak and Counting Crows, and had done two guest shots on The Tonight Show With Jay Leno.

Over that period, much attention was paid to the fact she gave interviews where she talked about being raped when she was 12. Indeed, she talked about whatever came to her head: her feelings about Tori Amos ("a poster girl for rape"), Maya Angelou (her idol), and psychiatric drugs (they help keep her sane). "There's no showbiz artifice in her," Slater says. "She's honest, and when you interview her, you get what she is on the day she shows up."

Then came the "Criminal" video. Set like the clip for "Sleep to Dream" inside a '70s-era tract house, it was styled in part on the photography of Nan Goldin, a chronicler of New York nightlife and isolation. Directed by Mark Romanek, the man behind Nine Inch Nails' "Closer," the video shows Apple after a long night of partying, surrounded by comatose teens whose faces are out of camera range, while she sulks, strips, writhes, lounges, bathes, hides, brags, and repents—"I've been a bad, bad girl"—because she took advantage of a boy she didn't really want.

"The first time I saw the script," she says, "it was like, 'Fiona in her underwear in the back of a car,' and I was all, What? I mean, I don't walk around the house in my underwear. I can't even stand to see myself in a mirror. But then the director said, 'It's tongue-in-cheek,' and I got it." Self-conscious or not, her vamping is undermined by an intense emotional honesty, and by the fact that she looks underage. In fact, so does everybody in the video. The clip transforms a song about girl power into a peep-show of teenage sexuality. Watching it, you feel as creepy as Humbert Humbert. The video suggests there's an element of rape involved in the way that pretty, sexy pop-star girls are presented in the media. It also helped "Criminal" into a hit single.

"I decided if I was going to be exploited, then I would do the exploiting myself," Apple says. This, of course, is a voguish sentiment. Apple grew up in an era of female pop stars thinking out loud about how to control their exploitation. Madonna felt powerful in her underwear. Among other things, her sexuality reclaimed certain kinds of submissiveness, presenting them as triumph, rather than surrender. In the current age of post-postfeminism, guys who were put off by Madonna's stridency are swarming back to the lure of more complicated and seemingly vulnerable girl icons, like Kate Moss or Apple. That's why her apparent vulnerability makes some enlightened sorts nervous. In addition to the real advances female performers are continuing to make in the music business, there remains the possibility that it would be easy to exploit the hell out of a girl and still claim that it's all about her power.

If it were the 60's, and Apple was Laura Nyro (a confessional singer/songwriter who, like Apple, cut her first record when she was 19), nobody would have put her in a halter top and asked her to be seductive. But now, Apple's message about what it's like to be a wounded, talented girl-growing-into-a-woman at the end of the 20th century is augmented by a media image she may not be able to control. "She obviously approaches things from a very raw state," says Apple's Lilith Fair colleague Joan Osborne, "and that's hard to sustain in the midst of being a pop phenomenon. If it happened to me when I was 19, I think I would have bugged right out."

David Corio/Redferns via Getty Images

David Corio/Redferns via Getty Images

Outside, it's 105 degrees in the San Fernando Valley. Fortunately, Apple's dressing room at the NBC studios in Burbank is aggressively air-conditioned. She's making her third appearance on Jay Leno, where she first performed on TV a year ago. Tonight she's doing "Criminal," and she's in front of a mirror getting her face painted. A makeup guy is talking in an assertively calm voice while he gives her what he calls "sort of a Carole Lombard 30's movie-star look." Slater, meanwhile, sits on the couch, along with Apple's tour manager and the manager of her record label.

Leno stops in to say hi. Apple's boyfriend, David Blaine, the downtown New York card-tricks fixture, is wandering around somewhere with Leonardo DiCaprio. Blaine's 24, a Russian-Jewish guy from Brooklyn, who has starred in his own ABC-TV special. "David and I are both completely fucked-up," Apple says. "We're the most fucked-up people I know." They're also as bratty and tender with each other as high school sweethearts. An hour earlier, after Apple had finished a run-through of "Criminal" for camera placement, Blaine rushed over, kissed her, and lifted her into the air like a swan. "I'm thinking of doing the song from up here," she said, and then he sort of dropped her, not really letting her fall but definitely letting her go, and she laughed and said, "You asshole."

In the dressing room, and hour to taping, Slater is discussing the creative process, "the place that artists go," when Apple interrupts him.

"Are you talking about me?" she says. Her eyes are heavily outlined in liner and shadow, and in profile she looks like Dresden china crossed with Marilyn Manson. "Because if you're talking about me, then it's not about 'a place you go.' Making music, I mean. It's about a place you get out of. I'm underwater most of the time, and music is like a tube to the surface that I can breathe through. It's my air hole up to the world. If I didn't have the music I'd be under water, dead."

Later, she does her number. Afterwards she's surrounded by a gaggle of flatterers and business associates watching her closely and telling her how good she was. Apple isn't impressed. She's standing in the middle of the crowd, clutching a red rose and saying, "Don't appease me." Then she goes with Slater into another room to have the kind of tense, hushed conversation that parents have with their brilliant, excitable children.

* * *

Fiona Apple was raised Fiona Maggart—Apple is from her grandmother, her dad's mom. Until about a year and a half ago, she was a neighborhood kid, and her 'hood was the Upper West Side of Manhattan. Currently, she doesn't have a home of her own. Blaine's homeless too, so when the two of them are together, they end up wherever. When she's on tour, her home is a bus. In L.A., she stays with her dad. But in New York, she stays with her mom, in the apartment where she grew up. It's uptown, near Columbia University and the borderline of Harlem. Riverside Church is nearby, where Spike Lee got married, and so is Grant's Tomb, and you can walk to the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, where Fiona and her older sister, Amber, appeared in holiday pageants.

On a Sunday night, a few days after the Leno shoot, Apple is taking me on a hometown tour, crisscrossing upper Broadway from Columbia down to 89th Street. Columbia is where Apple and her friends hung out together one summer. That was 1993, when Mary J. Blige's What's the 411? was the hot sound, and Apple and her teenage gang, broke and bored, scammed cabs up and down West End Avenue. They sometimes went into stores and took things. "You can do it if you have the right attitude," she says. "I'd go to the cashier and hold up a can of soda or something and say, 'I'm taking this, okay?' It always worked. I mean, I was a kid, I couldn't afford stuff."

Heading down Broadway, we run into friends of hers from grammar school, get stared at by surprised fans, and shop for vegan snacks at a health food store where the guy behind the counter only knows her as a local kid who won't eat anything with eggs in it. Then we hop the subway back up to her mom's place. "I'll never not take the subway," she says, "no matter how famous I am. If it reaches the point where I have to wear disguises, I will." To reach her apartment, we pass by black kids throwing a ball around in the August heat. Apple grew up listening to street rap and the soul-searching of college sophomores. It's a combination that shows up on her album, with introspective lyrics posed against a hip-hop beat.

Her mom's apartment is as big and cozy as you can get in New York without a trust fund. It's got a view of the Hudson River, high ceilings, exposed brick walls, sleeping lofts, a kitchen open to the living room's climbing plants, mood lighting, and an upright piano with a sticker on it saying, PEACE THROUGH MUSIC. We crash on the living room couch and she tells me stories: She woke up so angry one morning recently that she kicked a hole in the ceiling above her sleeping loft. When she was a little girl at St. Hilda's School, she went through a phase where her sister Amber was the Queen and she was the Dog, and lots of classmates were mean to her. She calls this period Dog Time. Once, at Amanda Wheaton's tenth birthday party, some guys made ten-dollar bets with one another to ask her to dance, so they could reject her when she said yes—the plot of "Criminal" reversed. She got mad and poured a bucket of cold water on them.

Her mom walks in the door, home from a bicycle ride. She comes in the room quickly and breathlessly, a funny, overgrown kid, kind of like her daughter. Unlike Apple, however, she doesn't seem to worry what people think of her. A line from "Never Is A Promise" might be addressed to her: "Your presence dominates the judgements made on you."

Apple's mother knows how to handle attention. Graceful as a dancer in her summer dress, she's got a lot of long black hair and an instant, quotable joke for the visiting journalist. "There's Fiona, my candle-burning vampire child, who stays up all night long and gets phone messages from Marilyn Manson," she says. "Every mother's dream." Actually, the name on the message pad is "Michael Jackson," Manson's current alias.

Mom floats away, and Apple and I compare zany mother stories. She says, "Does your mom do stuff like this?" She runs off and comes back with some dolls her mother made. They're two-foot long anatomically correct multicultural knit yarn dolls, African and Asian and Hawaiian, with nipples and pubic hair and little yarn penises, and one with a pink vagina. After that, she shows me her old high school yearbooks, just to show that her childhood had it's totally ordinary side.

David Corio/Redferns via Getty Images

David Corio/Redferns via Getty Images

Then suddenly she's talking about when she was raped. She doesn't wait to be asked about it; she just quietly tells me, sitting forward in an overstuffed chair with her feet splayed but her back straight and her head tipped down.

"I was in the hall," she says, "home from school. It was the day before Thanksgiving, 1989. I got off the elevator, and this guy came toward me, and I remember thinking that he wanted to hurt me." When she says "hall" and "elevator," she means the ones right outside the apartment where we're sitting. A few minutes earlier, I watched her look both ways when the elevator door opened, checking to see if anyone was out there.

"So I thought I'd better memorize what he looked like," she says. "In order to tell people later. Except, he kept coming toward me, and for some reason I started kind of hallucinating, like he was somebody else. He was Jimi Hendrix. Okay? I know that's weird. But I was a big Hendrix fan at the time, and I flashed on that. I was just getting over Dog Time, so it was like this turning point.

"Afterwards, I went out to L.A. to live with my father and go to high school because I was scared. I was scared for a long time. I didn't make any friends in California, so I came home, and took this self-defense course, 25 hours of it, five hours a day for five days, just fighting as hard as I could. And I told myself, I have to fight my way back. Because after the rape, I thought I was supposed to have died. I fought for that, I fought to be alive, I fought for here," she says, as if to indicate what she got in return: all the hype, the interviews, the guest appearances, the photo shoots. As she said back in Los Angeles, "I'm impressed with myself for getting here, but I'm not so impressed with here."

She's already cried by the time I reach the photo studio in downtown Manhattan, which is crowded with onlookers, including a bunch of Apple's friends from high school. There's catered food, huge windows, a sound system, and a black leather couch. Apple is standing behind some flats, out of sight with just her publicist and some stylists and the photographer. I hang on the couch with her friends. They're all about 19 or 20, but like Apple, they're such a wild combination of innocence and experience that it's impossible to pinpoint their actual age. We feed hip-hop music into the CD player, mostly Notorious B.I.G.'s Life After Death, and go watch Apple get photographed.

She's standing there, staring hard at the photographer, who's saying, "Give me sexy, seduce me." I can see why she hates photo shoots. "There's no hope for women, there's no hope for women, there's no hope for women," she says during a break, like she's the white girl rapper speaking out for her homies. She's full of the ghetto fatalism she learned from black performers like Tupac, who died on her birthday, and Biggie Smalls.

Later, the shoot moves upstairs and I'm sitting with Apple's friend Chris when she runs into the room in a Blanche du Bois house-slip, falls to her knees in front of us in a supplicating crouch, lifts her head like she's looking at a vision of the Virgin Mary, and says—confesses—in her whiskey voice, "I know I'm going to die young."

"Drama," Chris says in italics.

"No," Apple says, insisting. "No." She sees that the SPIN guy is sitting there with his pad on his lap taking notes, and this seems to be the image she wants to leave with him. There's urgency, anger, honesty, and a kind of brutal longing in her face, her voice, her arms tensed at her sides, her fingers laid flat and stiff on her thighs like rigor mortis is already setting in. She's been given a chance to be heard and she's terrified that now, instead of a handful of people not understanding her in grammar school, she's going to be misunderstood worldwide.

Tim Mosenfelder/Getty Images

Tim Mosenfelder/Getty Images

"I mean, it's not like I'll run home right now and shoot myself," she says. "But I know, I 'm going to cut another album, and I'm going to do good things, help people, and then I'm going to die."

It's a fact, not a complaint. She's certain. What she's certain about isn't her power but her vulnerability. Or rather, she makes you rethink your understanding of power. I remember her saying that the guy who raped her was much weaker than she was. "How much strength does it take to hurt a little girl?" she asked. "How much strength does it take for the girl to get over it? Which one of them do you think is stronger?"

She is strong enough to admit she's a mess. In fact, she may be the world's first self-demoting pop star. "It's impossible for me to be happy, psychologically and chemically impossible," she says, still kneeling on the floor. "So I'm going to help some little girl out there. I'm going to let her know that I have stretch marks on my ass, and bunions, that I don't have my shit together. I want to give that girl some hope. I want her to know that she doesn't have to have her shit together. She doesn't. It's okay if she doesn't. I'm going to prove that, and then I'm going to die."