Ben Sinclair’s favorite pick-me-up is an oat milk latte, because of the beneficial qualities of that particular dairy substitute: better for you than soy milk, better for the environment than almond milk or the stuff that comes from cows. Hemp milk is also a decent alternative, he explains. But picking hemp, in a sense, would be lazy writing. A guy like him, waking up each morning and downing a drink made from marijuana plants? It’s the kind of painfully obvious detail that would never fly on his show.

Sinclair is the co-creator and star of HBO’s High Maintenance, which premiered its second season January 19. Like the equanimous weed delivery guy he plays on TV, he is chatty and supremely comfortable around strangers. Unlike that character, whose personal life remains mostly hidden from the viewer, Sinclair has a disarming tendency to openly dissect his own motives, in social situations including but not limited to his choice of morning coffee.

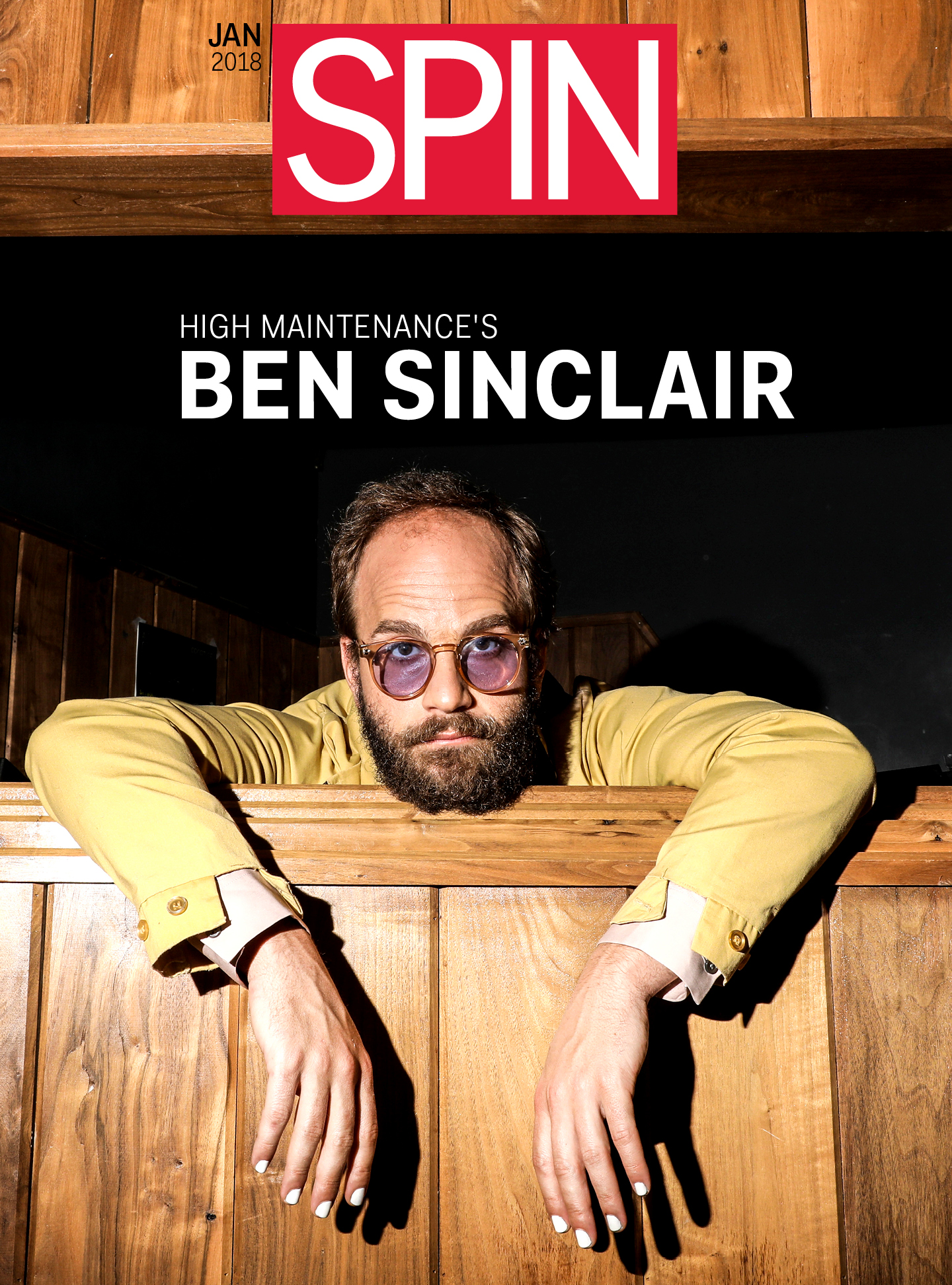

There’s also his fashion sense, which is several shades more vibrant than the jeans-and-flannel uniform of his onscreen counterpart. When we meet on the unseasonably warm Saturday morning after the premiere, he arrives outside a cafe in his Brooklyn neighborhood looking part Elton John, part Gandalf, part benevolent cult leader. Lavender shades, prismatic Coogi-style sweater thrifted on a recent vacation through Southeast Asia, denim jacket that would scan as normal New York dude if not for its wizardly ankle-length cut. He’s got a fleck of spittle in his beard, a clutch of pink roses in his hand, and a helium balloon the size and shape of a modest exercise ball hovering dreamlike above his head, also in pink. All three accessories, I assume, are left over from the premiere party he threw in his nearby apartment last night, which ran late.

High Maintenance started life as a cultishly beloved web series, offering a spin on the classic monster-of-the-week format, except instead of monsters, it’s a panoply of neurotic New Yorkers who all buy their weed from the same nameless bike-riding dealer. Rather than cracking hackneyed jokes about hallucinations and ice cream binges, the show presents pot as a routine, even mundane, aspect of life. Weed unifies an otherwise disparate cast of characters, and the allure of weed culture is good cover for the show to investigate heavier subjects, like loneliness and aging. It is both savagely funny and warm in a way that’s almost sentimental, satirizing the millennial urban experience while maintaining empathy for the Uber drivers and freelance design consultants who have no choice but to live it. The Guy, as the dealer is known, is sometimes a central player, but more often, he flits in and out of the drama, selling pot to help a middle-aged birdwatcher cope with a troubling medical diagnosis in one episode, and to crusty former communards who have graduated uncomfortably to yuppiedom in another.

Both Sinclair and The Guy are fairly high-grade stoners. Sinclair tells me stories of eating mushrooms and going scuba diving (“So stupid, but while I was down there I wrote sort of a Brokeback Mountain for scuba diving scenario”), taking edibles and running a marathon (“So fun, you take it at the beginning and it kicks in right as you’re hitting your stride ”), and doing multiple gravity bong hits and taking meetings with High Maintenance producers and assistant directors (“Could they believe they were trying to fulfill the vision of someone who was that fucked up?”). Both are frank and inquisitive, and they move through the world with enviable grace, traits that people sometimes take as invitations to open up and begin unloading. Several of them approach Sinclair over the course of our Saturday together wanting to talk, some fans of the show, others who just seem to appreciate his clothes and sagelike demeanor. Many of High Maintenance’s most memorable moments also involve The Guy acting as ad hoc therapist for his clients.

This happens with us, too. At a photoshoot earlier in the week, he asked me how I’d been since the last time I interviewed him, in 2015, when High Maintenance was still publishing episodes to Vimeo. Not wanting to interrupt the task at hand, I gave him a noncommittal “Oh, y’know.” “Actually, no, I don’t,” he answered, politely but firmly, and waited for a more substantive response.

Two days later, Ben Sinclair knows more about the intimacies and complications of my relationship than several close friends.

Sinclair’s pink ensemble has something to do with our destination for the day: the second Women’s March in Manhattan, the one-year anniversary of the massive protests that marked Donald Trump’s first day in the White House, and the subject of a hilarious scene in the second episode of High Maintenance season two. As we board a packed train from Brooklyn into the city, he’s still carrying the balloon, which he plans to use as a kind of koanic protest sign, telling everyone who asks that it is meant to represent an ovary or an egg.

The first march came at an especially dark time for Sinclair. In addition to the malaise that most liberal people felt at the time, he’d also separated from Katja Blichfeld, his ex-wife and High Maintenance’s co-creator, on the day of the election. She’d recently come to understand that she is gay, a revelation that meant the end of their romantic relationship but not their creative and professional one. They made their decision to break up, saw the dispiriting results come in, watched a few episodes of Friends, and went to sleep in separate beds. Working together was understandably difficult at first, but according to Sinclair, it eventually became easier than it had been the previous season, when they were avoiding discussion of their marital problems out of fear of ruining the show.

“Katja has said a number of times, and it’s not untrue, that we had a contractual obligation to fulfill to HBO—but also, we’d already started some of the series,” he says. “We had a week of writing under our belts, and I went to the march by myself. I got kind of freaked out. There was a lot of, ‘Hey, it’s the guy from High Maintenance,’ and I felt really weird and insecure about being there, especially since I just broke up with a woman who was into other women. I felt like, ‘This is supposed to be a day about you,’ and I was trying to meditate about that.”

That night, he went on a bender with friends and new acquaintances that ended at 5 the following morning and involved a quarter tab of acid and other substances he declines to mention by name. He’d made a new year’s resolution to cut down on pot, which he technically hadn’t broken, but he woke later that day feeling pathetic: You’re just acting out all your married-man desires, he remembers chiding himself. Still, there was a bright side. Sinclair’s wild time formed the basis for an upcoming episode, about a twentysomething Hasidic jew—played by a real ex-Hasid—who leaves the community and celebrates his freedom with a cathartic and nearly disastrous night out clubbing in Brooklyn.

On the train, we discuss our conflicted feelings about masculinity, the gendered nature of various storytelling tropes, and Sinclair’s post-divorce attempts to confront his own insecurities and ego. He’s intensely self-examining, and says he developed his own sense of humor and hunger for the spotlight as the youngest child of four in a family where material resources, and attention from his parents, were sometimes scarce. His mother was a synagogue cantor; his father cycled through jobs including fourth grade teacher and Cuban restaurant maître d'; one sibling is a Democratic congressional candidate and another writes for Chicago Med.

The car fills with prospective marchers, some of whom recognize him and congratulate him on the previous night’s premiere. One person asks us to move further in, but there’s nowhere to go. At this point, it becomes impossible to ignore the comic hypocrisy of our situation: two men talking about being good feminists while crowding out a bunch of righteously angry women from the train car with our extremely large pink orb. “Here I am with this fucking balloon,” Sinclair says at the end of a monologue about making room for women’s voices. “I don’t know what I think I’m doing.”

***

Out in the crisp midtown air of the march, Sinclair’s balloon is free to bop around, ducking and weaving above the crowd. Between the premiere party, jetlag from his recent vacation, and a few marathon press days leading up to the premiere, Sinclair is wiped out. But he’s also visibly moved by the communal spirit of the day, chanting and taking photos with a disposable camera. Last night, he filled his apartment with as many High Maintenance team members and friends of the show as it could hold, including Blichfeld and her new partner. As a gag, he wore silver colored contact lenses he’d picked up in Tokyo, which blurred his vision. For whatever reason, his ex-wife’s new girlfriend was the only guest he could recognize with any clarity. “I definitely didn’t go too fast with her, but I really like her,” he says.

He perks up when we run into three friends he knows via a connection made at an ayahuasca ceremony. After a morning spent fretting over the meaning of male allyship, we have finally met up with some women. The clear leader of the pack is Gaby, who wears a bright red topcoat and shares Sinclair’s goofball charisma, introducing herself as “the Gabster.” As if they were expecting us, she and her sister produce two leftover breakfast sandwich halves to eat, and a joint for all of us to smoke later. The Gabster regales us with a story about partying too hard with a certain controversial tech company founder on New Year’s Eve, who was nearly thrown off a chartered boat for drunkenly tossing a bunch of tortillas overboard into the water.

All afternoon, Sinclair has been wondering aloud about the effects of what he sees as his very male desires for attention and control. On one hand, they’re part of what makes him so compelling to watch and to be around, and he wouldn’t have co-created or acted in High Maintenance without them. On the other, according to him, they can also be destructive to relationships; when he’s being particularly hard on himself, they even make him feel like Trump.

But he’s working on it. Part of his journey after the divorce, he told me earlier in the day, was “coming to terms with my alphaness: It’s helpful. It feels good to feel secure. But so many alphas do crazy things out of insecurity because they want to feel secure, and it’s just important to notice the insecurity too. Why am I doing this? Oh, is it because I don’t feel comfortable right now? Why am I making other people do things that just have to do with me feeling comfortable?”

When the Gabster finishes her story about the belligerent billionaire, Sinclair’s balloon wanders toward the branches of a nearby tree and promptly pops.

***

Blichfeld and Sinclair tend to write from life, both their own (While still married, they joked with an interviewer that “All the episodes are about us. The assholes are about us, too,”) and from snatches of observation and overheard chatter. Late in the day, Sinclair and I encounter a group of teen boys and girls who are screaming with near-religious intensity about their decision to abandon the march and go shopping instead.

"We're going to Urbaaaaaaaan," they yell, running to the door of the store.

“Dude, what a gift,” Sinclair says. “You walk around the city, and you just hear shit like that. And you’re like, oh my god, I get to use that on my show?”

https://www.youtube.com/embed/HjQpIXU2eY0

High Maintenance excels at capturing the humanity of characters like these, sparing them from heavy-handed judgement. Danielle Brooks, best known for her performance as Taystee in Orange Is the New Black, plays a Brooklyn real estate agent who’s caught between the gears of gentrification: a lifelong resident of a historically black neighborhood, she peddles apartments to white newcomers, earning her rent by accelerating forces of change that could ultimately price people like her out of their homes. It’s a sharp and nuanced story that’s critical of the status quo without banging an obvious moral over your head—and High Maintenance might not have been able to tell it if not for Sinclair and Blichfeld’s divorce.

For the second season, the pair invited outside writers and directors to work on episodes for the first time ever, who served both to ease their workloads and to act as buffers between them during the strained period after their split. Brooks’s character was conceived by Shaka King, a black filmmaker born and raised in Bed-Stuy. Initially, King pitched an episode about a black weed dealer whose business is cannibalized by an influx of white cyclists like The Guy, selling oil pens and multiple potent strains. Given the wildly divergent rates at which white and black people are arrested for pot in New York and across the country, perhaps he would be targeted more often than The Guy and his clients, for whom weed’s status as an illegal drug rarely presents a problem. Sinclair and Blichfeld loved the idea, but it was too ambitious for High Maintenance’s format, which tends to cram multiple stories into a single 30-minute episode. So King rearranged the narrative around Brooks’s character, one of the black dealer’s clients. “I still want to have that dilemma,” King tells me in a phone interview. “Do I support the guy I’ve been going to, who I’ve been able to call at 4 a.m. and he shows up at my doorstep? Or do I want this fancy thing? And for Danielle’s character, it isn’t really a dilemma. It’s pretty much an easy choice, because she’s a capitalist.”

Sinclair and Blichfeld’s work, though wholly fictional, has a certain journalistic streak, spinning out details culled from true experience into larger narratives that say something significant about the world. Their impulse is not entirely different from mine, in other words. The difference, of course, is that TV comedy writers owe no fealty to the literal truth, nor do their characters generally kvetch to them about feeling misrepresented. At the march, Sinclair mentions a recent New York Times profile of him, which he believes seized too readily on details like his enthusiasm for hallucinogens and attendance at Burning Man, in an effort to portray him as a sort of stock character: the wacky bearded Oberlin grad, experiencing his charmingly offbeat version of a midlife crisis.

“This guy pointed out that I’m way more anxious than The Guy, which is true,” Sinclair says. “But at some times, it felt like, ‘Oh, he’s nothing like him.’ And I’m like, ‘Yes I am! I’m a lot like him.’”

***

On the Monday after the march, Sinclair posts a photo of the two of us to his popular Instagram account. The balloon, digitally resurrected and frozen in time, sails behind him, catching a few rays of sunlight. “How incredible is [it] that over two years of marching, millions of people can come together to express anger and dismay at the status quo, and there are no acts of violence?” he wrote in the caption.

He calls me a few days later, anxious about the way he presented himself when we were together, in large part because of an eye-opening conversation that happened in the comments of that Instagram post. “Congratulating yourself for having a peaceful protest is a slap in the face of your fellow POC protestors,” a follower wrote, paraphrasing the Huffington Post journalist Zeba Blay. “There’s an implicit assumption that any gathering of brown or black folk equals trouble....The presence of white women at the march served as a kind of buffer to police and that PRIVILEGE is what kept it physically non violent.” Sinclair reconsidered what he had written and agreed with the commenter. He thought about deleting the photo or amending the caption, but worried that doing so would allow him to escape reckoning more seriously with what he’d written.

[caption id="attachment_id_276692"]  Photo by Krista Schlueter for Spin[/caption]

Photo by Krista Schlueter for Spin[/caption]

The exchange was uncannily similar to a conversation between characters in the second episode of High Maintenance season two—which had not yet aired at the time—featuring a group of white women crafting protest signs for an event that sounds a lot like the second Women’s March. Sinclair previously told me that the scene was conceived early in the writing, and had initially featured a different group activity, but was rewritten after Trump was elected. “Everyone was like ‘Oh, it was so peaceful, great job protesters,’” says a woman played by Molly Knefel, who writes and podcasts about progressive politics in addition to acting. “The police decide whether they escalate something or not. I’m not interested in praising the police for not beating the hell out of people. In Ferguson, the police react very differently to the protesters, and that’s because of racism.”

Knefel had improvised those lines, Sinclair tells me on the phone. “I edited that moment, but I guess I didn’t hear it fully,” he says. Before I mention anything about the contents of my article, he rattles off nearly every detail in it, construing them as evidence that he was trying to make himself look good, that he wanted attention, that his actions didn’t live up to his stated ideals: the balloon, the beautiful pink outfit, the moment on the train, the fact that his team suggested the Women’s March as a venue for the interview in the first place—even the oat milk. “When we had initially planned to do it, I had a moment of, wait, maybe this looks like I’m trying to look a certain way,” he says. “And to a large degree, I was trying to look a certain way. I was conscious about being there. I think the self-consciousness and self-reflection is probably helpful and necessary, but it doesn’t add up to anything if your actions don’t change. If I felt weird about the first women’s march, for being the guy from High Maintenance, maybe I should have worn something else.”

“I want to be completely transparent in this new version of myself that I have post-marriage," he goes on. "As a single white man and television dude, woke, whatever."

He also faults himself for something I didn’t even realize might be taken as insensitive: the fact that we’d smoked the Gabster’s joint. He was exceedingly cautious about the elevated police presence at the march, but even so, he says, our status as white guys helped us get away with it. The previous night, he’d made an overture via his publicist to have any mention of our smoking cut from the article. He makes a fine point about privilege, but I push back a little: wouldn’t censoring the joint undermine High Maintenance’s message that weed is a great unifier of people, and nothing to be ashamed of?

On Saturday as we were leaving the march, the weed didn’t feel like a sociopolitical fire hazard; it just felt like good weed. The sun took on a pleasantly intense clarity through the tall buildings as we strolled down Fifth Avenue. An eccentric older Manhattanite sidled up between us, looking and acting like a High Maintenance character, in a gorgeous ankle-length coat that almost matched Sinclair’s. She talked at length about her attempted career in the theater as a younger woman, and it was obvious she had no idea that Sinclair himself is a fairly successful actor. He was free of any apparent anxiety, fully in Guy mode, listening sensitively, peppering her with thoughtful questions.

After a few minutes, unable to stand the dramatic irony any longer, I told her that Sinclair starred in a very good TV series that had its season premiere on HBO the night before. He started geeking out a little, because he knows good material when he hears it. “It’s funny,” he said. “We’re actually on an interview right now, he’s interviewing me for a magazine. And I’m just thinking to myself, he’s just loving this right now.”