The sound is a clue to the state of a rock band caught at another moment of evolution, equally connected to their past, present and future, still rockers at their core after two decades, but aspiring to expand beyond that. The Monkeys are here headlining the final day of Primavera Sound, the international Barcelona-based festival making its U.S. debut in L.A., drawing 50,000 fans into L.A. State Historic Park.

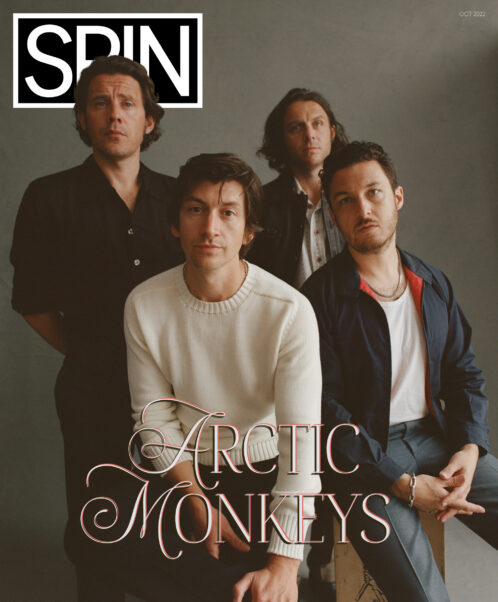

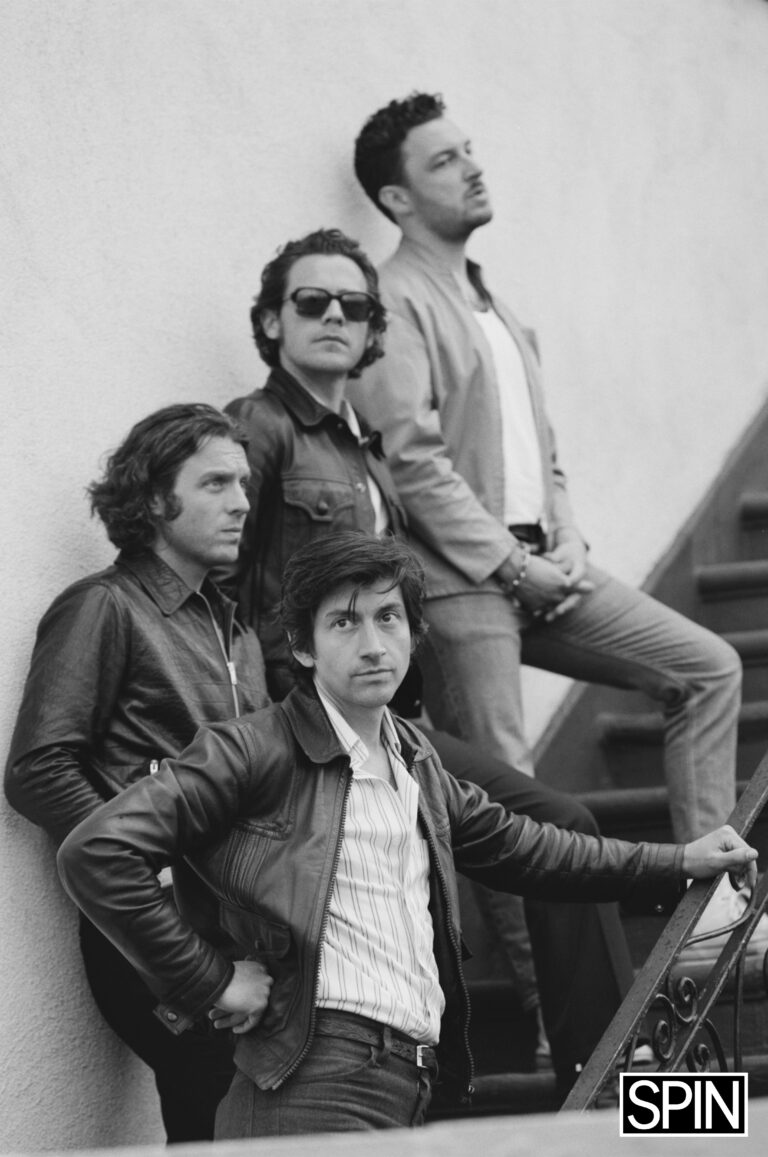

The Arctic Monkeys have been at this since they were teenage mates bashing out modern guitar rock with emotion and bite, quickly growing into superstars in the UK, and festival headliners in the U.S. and everywhere else. The band’s core band members – singer Alex Turner, drummer Matt Helders, guitarist Jamie Cook and bassist Nick O’Malley – are augmented tonight by three other players. The sound is arch and sophisticated, like a next-generation Roxy Music, noisy and unruffled through clanging guitars, alluring piano melodies and lyrics wide open to interpretation.

The biggest international hits would come later in the set, but early on they share a song from the band’s new album, The Car, a shimmery funk tune called “I Ain’t Quite Where I Think I Am.” The song is ready for the dancefloor or your nearest smoke-filled room, as Turner’s voice goes higher, if not quite falsetto, singing soulfully of a dystopian future (or dystopian present): “Freaky keypad by the retina scan…”

With a disco ball at his feet, Turner doesn’t say much between songs, but never comes off as distant, either leaning into the mic or strumming his guitar. When he does speak, the words are as opaque as his lyrics, ending one song with a teasing: “Yes, you like that? I understand loud and clear. Don’t make a big deal out of it.”

Two weeks later at a mostly deserted boutique hotel on Hollywood Blvd., Turner is sitting at a table with a nearly empty bottle of sparkling water and a small paper coffee cup. With a lock of hair dangling stylishly over his forehead, he is wearing an embroidered Guatemalan shirt over a faded block top.

As a host, Turner is perfectly relaxed and cordial, but chooses his words carefully during our interview, finding the messages he wants to convey slowly. Seeing his words in print since he was barely 20 no doubt brought him to this careful state, but he also looks pleased when you recognize one or another inspirational touchstone (Mick Ronson, Brian Wilson, etc.) in the new songs.

In town to talk up the album, the bar is a convenient meeting place. On the wall behind him is a collection of ancient class photographs, of strapping young men in school, on sports teams, all forgotten memories from the last century. “I hadn’t noticed that. Actually just been too busy making it all about me,” Turner says with a knowing laugh.

The whole band lived in L.A. for a time, but now only drummer Matt Helders remains, and between Monkeys projects is a member in good standing of Joshua Homme’s rotating crew of players and accomplices. (Which meant being recruited in 2015-16 for Iggy Pop’s Post Pop Depression.) While Turner still likes to squeeze in some quality time in the city, he now mostly bounces between London and Paris, usually accompanied by the French singer-songwriter Louise Verneuil.

A few days after Primavera, the band headed out to New York for a quick visit to premiere more songs from The Car on The Tonight Show and at Brooklyn’s Kings Theatre. It’s an album The Guardian has already praised as a wide-ranging collection of “Portishead-stark noir, improbably catchy yacht-funk and … poppy bombast.”

Two decades after forming as a band of neighborhood teenagers in Sheffield, England, the Arctic Monkeys have maintained relevance as artists and hitmakers by following their own creative impulses rather than passing trends. They began as excitable rockers with flinty bad attitude and pop instincts, quickly hitting No. 1 in the UK with their anxious second and third singles, “I Bet You Look Good on the Dancefloor” and “When the Sun Goes Down.” Compare that with The Car, and the evolution to music of increasing sophistication is startling and undeniable, with Turner growing from sneering punk to multiple layers of feeling.

Historically, you might compare Turner and the Monkeys’ evolution to Bowie’s mid-’70s leap from edgy rocker Ziggy Stardust to the deeply emotional crooner of Station to Station and Heroes, and still always sounding like no one but himself. Helders began to notice a change in the vocals when Turner started working with his other project the Last Shadow Puppets, which then carried over into the Monkeys. “It was less shouty and fast and more like Walker Brothers singing. He’s leaned into that a lot more vocally. I’m like, ‘Oh wow. You’re actually a singer now,” Helders says later on the phone, laughing.

In 2022, as much as the sound has changed over time, Turner insists the core quartet is still “following our instincts, which is precisely what we were doing in the summer of 2002.” They were kids then, and songs were composed in that early stage around their abilities in the rehearsal space, designed to be played live in a small club. They now record music with no concerns about recreating the same sounds onstage, allowing their creative impulses to drive the recordings.

He’d grown up surrounded by music, his father, David Turner, a big band musician and educator who actually sat in with the Last Shadow Puppets during a 2016 set in Berlin, blowing sax on “The Dream Synopsis.” That early influence not only reached young Alex, but the friends who came over to the house, including future members of the Arctic Monkeys.

Long before he was a musician himself, Helders heard a lot of mysterious sounds from the distant past at the Turner home that most neighborhood kids were not, learning of an earlier generation’s iconic figures that definitely weren’t being written about in NME.

“When I went around to his house – which was often – big band and jazz and swing was on,” says Helders. “It has always been a powerful thing for Alex. And me too. When I first saw Buddy Rich playing drums on TV, it was before I played drums. I didn’t really understand what was happening. I was like, ‘Whoa, this is blowing my mind!’

“There’s just so much feeling when you listen to music like that,” he adds, noting their current use of Stan Kenton as intro music. “Musically it’s like a masterclass. We’re not quite there yet, but maybe it is enough to know what skill level we’d like to be at.”

The musical lessons kept coming, even as the Monkeys grew into a leading force in a new wave of British rock and pop music, with their every move documented and scrutinized.

The band experienced a career-altering revelation while working with Homme as co-producer on 2009’s Humbug, which in hindsight looms even larger in their story. Rolling out into the high desert to make that album with the Queens of the Stone Age leader opened their eyes to the freedom available to them as artists. Getting weird was something to be embraced, not avoided.

Helders says, “It was Josh who said, ‘Whatever you do in this room, it’s still you. No one can tell you it’s not you. You’re doing it.’ As simple as that sounds, it makes sense. It made us feel like, Oh, we can do whatever we want.”

They’d first met the tall, redheaded rocker backstage at a Belgium rock festival. “We heard him coming down the corridor shouting ‘Monkeys! Monkeys!’” Turner recalls with a smile. Arctic Monkeys had been open in the press about being fans of QOTSA, and now, “He’d come looking for us.”

After that encounter, Domino label co-founder Laurence Bell suggested they reach out to Homme to see if he would be interested in producing. He said yes, and guided the band through seven songs on Humbug. (Four other tracks were produced by longtime collaborator James Ford in New York City.) Looking back, Helders says their first trip with Homme to the Rancho de la Luna recording studio, way out on the edges of Joshua Tree, “felt like I was on another planet.”

“Had we not had that experience at that time, I’d question whether we would still be going now,” Turner says thoughtfully. “At that moment, it felt as if we were put in a bit of a dead end, and creatively it felt like we’d ran out of steam a little bit.”

The Monkeys eventually returned to Joshua Tree (minus Homme) and came back with the monster album of their career to that point, 2013’s AM, which reached platinum in both the UK and U.S. The songs mixed G-funk rhythms with their edgy guitar rock and Turner’s words of romance and ruin. Songs traveled from the crunchy riffs of “Arabella” to the swaggering, woozy funk of “Why’d You Only Call Me When You’re High?” Mojo called the album “exciting, audacious work,” and NME declared, “Smart, randy and touched by genius.”

The wildly enthusiastic public reaction that greeted AM didn’t lock the band into a sound, or pressure them to produce sound-alike albums. If anything, it only freed Arctic Monkeys to do as they pleased, to follow their meandering muse wherever it led them.

The band’s last album, 2018’s sci-fi conceptual Tranquility Base Hotel & Casino, threw things for a loop. The Car is another step forward, unimaginable in their early days as a stripped-down rock act. Back then, the quartet were on a mission to be as new and original as they could. Helders made a point on the early records to create new beats that were flashy and technically difficult, looking to always “make this new weird thing,” he says.

“That was great for then and it matched what we were doing with the riffs and maybe the aggressiveness of the singing,” he adds. “Now I appreciate restraint and being able to play a groove in a really good way. It’s not any less fun for me, contrary to what it might look like. Even though the drumming is calm and more laid back, it’s as much fun as it is to play more showy.”

The new album’s gently urgent closing track, “Perfect Sense,” came together quickly, with strings mingling with drum beats to create a swirling Brian Wilson flavor. The Beach Boys maestro “has always had a place in my heart,” Turner says. “That’s been in the back of my mind since I was a five-year-old kid.”

The lyrics paint a murky, playful picture: “Having some fun with the warmup act/If that’s what it takes to say goodnight then that’s what it takes. … four figure sum on a hotel notepad … A revelation or your money back.”

“I suppose overall none of it makes a great deal of sense in the traditional sense,” Turner acknowledges happily. “It’s like when you’re trying to leave a party and this is like the fifth attempt. Okay, now I’m really going. That’s what it sounds like to me.”

On the album cover is a photograph shot by Helders in downtown Los Angeles, looking down at a lone car parked on a rooftop lot amid other tall buildings in 2019. The drummer is serious about photography, has published a book of pictures from the Tranquility Base sessions and shown in galleries. For that photograph, he was simply trying out a new lens on his Leica, walking around the city or shooting out his bedroom window, inspired by vivid color work of master photographer William Eggleston.

Helders liked the picture and included it with some others he shared with Turner. “He was like, Oh, wow. He kept coming back to it, like, ‘There’s something about that photo. It tells a story somehow.’” The singer eventually wrote a song inspired by it, and began thinking of the album as The Car, with that image as the cover.

On the title track, as Helders plays brushes on record for the first time, Turner sings his evocative, mysterious, disjointed lyrics: “Your grandfather’s guitar, thinking about how funny I must look trying to adjust to what’s been there all along ... But it ain’t a holiday until you go to fetch something from the car.”

Ahead of the sessions with the band, Turner wrote and recorded preliminary demo versions of the songs, written half on acoustic guitar, half on piano. He sensed where the album was headed when he landed on the instrumental section that begins the opening track “There’d Better Be a Mirrorball.” “That felt right,” he says, “and of course the words have to get on board with that.”

They recorded basic tracks for The Car in an ancient, 700-year-old house called Butley Priory in the English countryside of Suffolk. With arched windows and walls made of stone, the two-story building has recently been refurbished as an elegant venue for weddings and other events. With producer Ford, the Monkeys rented it out and transformed it into a studio.

Says Helders, “We managed to make it feel like a place you wanted to make a record.”

The idea was to somehow replicate scenes Turner had read about, of Led Zeppelin or the Rolling Stones camping out at a large country home, and parking a mobile recording truck outside. In the ‘70s, a truck had to be packed with recording gear: tape machine, mixing board, speakers, plus engineers and the producer, with cables running into the house.

Loren Humphrey, a frequent Monkeys engineer in recent years, had given Turner a copy of the book The Great British Recording Studios, and the singer became fascinated with its pictures of the famous Stones Mobile Studio unit, with its linoleum floor and history of recording multiple classic rock albums. Modern digital equipment has made the need for a mobile unit mostly obsolete, but the idea of recording at a home in the country stuck in his mind.

“That was kind of the dream idea, but we didn’t quite make it all the way to the linoleum floor in the truck,” he says with a grin. Band and crew instead loaded in their gear and computers and got to work. The band also lived on-site during the recording, and between sessions would gather in front of broadcasts of the 2021 UEFA European Football Championship, where England got to the final.

“That was a pretty exciting time in England then, and we were all watching the games and hanging out,” says Turner. “We hadn’t seen each other for a while and I think that got that kind of the energy of the band back together again.” Helders recalls sessions being structured around soccer viewing. “It really dictated the mood,” the drummer says. “If England had a bad game, it wasn’t going to be a good day in the studio.”

For the band, now looking back at 20 years of history, the sessions were a throwback to the Monkeys’ debut album, Whatever People Say I Am, That’s What I’m Not, recorded in 2005 at Chapel Studio in the countryside of South Thoresby. That album might not have happened any other way.

“If we were in a city, we would’ve never finished that record,” Helders says with a laugh. “We needed the discipline of like, ‘Okay, we need to do a song every day. We don’t want any distractions.’ We were just teenagers.”

Sessions for The Car were delayed for a year because of COVID-19 restrictions. It took time for Helders to get back to England from L.A., and he was required to arrive first so he could quarantine ahead of the rest of the band and crew. But Turner used the year to refine his songs, to experiment and explore “a few blind alleys” without concerns about time.

Later, vocals and overdubs were recorded in another house in France, where Turner picked up a 16mm movie camera and captured footage of the band at work, handing it off during his vocals. Some of those grainy color and black-and-white moments turn up in the music video for “There’d Better Be a Mirrorball.”

“I found that having the camera kind of removed me a bit from the situation and hopefully allowed a bit more space for the band to fill,” he says now of his foray into filmmaking. “It gradually transformed itself into a promotional music video, so it all happened pretty naturally.”

In London, strings were recorded at RAK Studios, not to add “sweetness” but evoke complex emotions. That final ingredient is essential to the sound of The Car, contributing to its 10 tracks a consistent personality, a bit like an old Sinatra record as arranged by Nelson Riddle.

“Those arrangements of Sinatra were definitely on when I was in the passenger seat as a kid,” says Turner, whose songwriting usually begins on piano, where he sometimes drifts towards the kind of chord structures his father played at home. “But obviously it’s not swinging quite in the way that stuff is.”

For all the willingness to slow down and use understatement along with noisy guitars, the Monkeys remain at their core a rock band. So Turner embraced the idea of using each piece only as needed, with the strings rising at one moment, then disappearing as the rock instruments roar back. With Tranquility Base, the band looked to create a consistent sound and mood from song to song, and The Car takes that a step further, sounding like a larger work rather than a collection of songs.

“I think we’ve done a better job this time with the dynamics of the whole thing, like allowing each element to have its space and come into focus and disappear when the time is right,” he says. “I felt like there had to be some caution, like the alarms going off: Don’t just go throwing the strings on top of the rock band sort of thing. Let’s try and find a way that it can sort of take turns. There was an idea before the record about splicing two things together from a totally different time and space.”

“Body Paint” captures that balance, starting gently with strings before leading to an explosive guitar piece played by guest Tom Rowley. Turner hadn’t imagined that particular crescendo when laboring over the song alone in a room, before reinterpreting it with the full band. “Having everybody there, it gives you that energy of the band you can’t really replicate,” he says, adding he welcomes the surprises.

There is also an undeniable strain of funk across the songs, which marks a different kind of blast from their past. “It did probably start with opening the drawer and finding the old wah-wah pedal again from 15 years ago,” says Turner. “I’m thinking, ‘Wow, let’s audition that again in this creative juncture.’ When we played it in rehearsal in the first place, it was exciting to sort of blow the dust off the wah-wah pedal.”

That makes The Car a record they could only have made now. The original sound and energy of the Arctic Monkeys wasn’t ready for it. They weren’t self-aware enough to have such aspirations.

“We wouldn’t have been able to do this 10 years ago, or 15 years ago,” confirms Helders. “Everyone sort of learned their instruments at the same time, at the same pace and got better. We’ve got to a place where we can make music like this.

"I think everything happened at the right time.”