I’ve been working at SPIN since fax machines were indispensable and phone conversations were unavoidable; and my tangential relationship with the magazine goes back to a time when Reaganomics and hip-house were serious personal concerns. What began as an extended hookup based around a desperate desire to find a music-related job in New York that wasn’t totally soul-crushing has now reached a level of entanglement that often verges on the pathological. Hysterically self-righteous apologias, grim outbursts of disgust, mass consumption of prescription and nonprescription “medication.” In other words, a marriage. And what’s more, a marriage that revolves around listening to records and glorifying or betraying the people who make them. Daft, huh?

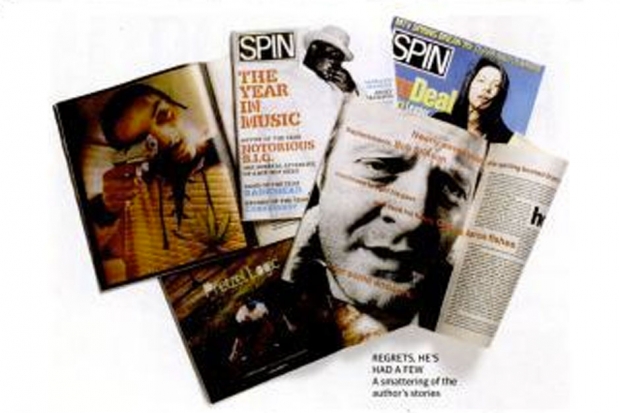

People, or at least friends and family, sometimes ask how? Or why? But on the occasion of SPIN’s 25th anniversary, it seems more apt to ask what the fuck? So, in the storied rock-critic tradition of of preposterously pretentious introspection, I’ve decided to gawk at my SPIN tenure through the prism of Ingmar Bergman’s cinematic riff Scenes From a Marriage, a series of six vignettes that poke and prod a Swedish couple’s crumbling intimacy and eventual rapprochement (of sorts). For me, working at SPIN has been about poking and prodding my ongoing fling with pop music — an indiscriminate flailing for kicks and redemption — past the point where most people wise up and convince themselves that watching Yo Gabba Gabba! with their kids is cool enough (which it is).

The critic Phillip Lopate notes a revealing moment in Scenes From a Marriage, which applies to my own poke and prod: “When she wakes from a nightmare and suddenly seems to subscribe to his pessimistic view of life, even doubting that she has ever loved anyone, he is there to comfort her with a reassuring pirouette, saying that indeed they have both loved each other in their selfish, partial, human ways.”

Also Read

Every Replacements Album, Ranked

Selfish, partial, human. Happy 25th, SPIN, you codependent bitch.

1. Innocence and Panic.

Couch surfing begat everything. Minus free sofas to crash or drool on, or to hide one’s stash in, how would any creative hustle ever get off the ground? My couch-surfing break came in early 1985, when I washed up in Manhattan, after roadtripping from the University of Georgia in a soon-to-be graffitied VW Beetle. I was crashing with my de facto mentor Chuck Reece, an ardent journalist and music geek who’d moved here after graduating from UGA (and having a disastrously ill-advised affair with my ex-girlfriend, which gave us an even tighter, if twisted, bond).

Whether I knew it or not at the time, two volatile characters, via Chuck, would soon help determine the course of my life: (1) Bob Guccione Jr. and (2) Paul Westerberg. The first, the ambitious spawn of America’s Caligula; the second, my white-trash Catullus, a lyric poet of boozy folly whose songs with the Replacements offered a sloppy embrace to anyone whose heart had been obliterated, either by a lover or society.

One night, Chuck came home and told me about this guy he’d interviewed who was starting a magazine that supposedly was “like Rolling Stone used to be.” The punch line: The guy’s dad was the publisher of Penthouse. When I recently called Chuck, a longtime Atlanta resident and former press secretary for Georgia governor Zell Miller, he laughed wryly. “Guccione was giving me his rap about SPIN, and all I could think was, ‘Goddamn, I’m sitting here with the son of one of the two biggest pornographers in the world.’ It was like I was having this flashback to being a horny kid in Ellijay, Georgia, and I just wanted to say, ‘Man, you probably got to see all the titties you ever wanted to when you were growing up!'”

They talked about their favorite records — for Chuck, the Replacements’ Let It Be and the Del Fuegos’ The Longest Day, two heartache opuses. Before long, he had an assignment to write about both bands for the debut issue. It was a mixed blessing. “The Del Fuegos were the sweetest guys, but the Replacements were a mess. I flew down to Atlanta to meet them at the 688 Club, where they had a show, and when I walked in, [the band’s notoriously unhinged guitarist] Bob Stinson came right up to me with this big smile on his face. I’d seen them play before and had met them, but he couldn’t have remembered who I was. Anyway, first thing he says is, ‘Man, you know where I can get some crank in this town?’ Then Paul came running up behind him, going, ‘No, Bob, no!‘ Like he was talking to a dog.”

The meet-up the next day with Westerberg was a fiasco — “He was a surly son of a bitch, hung over, didn’t want to be there, terrible interview.” Regardless, Chuck poured his heart into the story, even artfully invoking the girlfriend who two-timed us both. Unfortunately, when the May ’85 issue of SPIN appeared, the entire first section of his piece had been lopped off. Nobody bothered to call and explain. Something about ads dropping out and pages being cut, apparently.

Chuck was so pissed he never wrote for SPIN again. Back at school, I filed Guccione and SPIN as typical New York assholes who talked a big game, but ultimately just dicked people over. We both still loved the Replacements, but our giddy innocence had been replaced by a creeping fear, even panic, that believers like us, who harbored a post-hippie hard-on for something true, were destined to get chumped.

2. The Art of Sweeping Things Under The Rug.

By 1993, the world, at least viewed from my Brooklyn crawlspace, was a blur. The Replacements had imploded and Nirvana had exploded, SPIN was the voice of a genre called “alternative rock,” and I was just another so-and-so begging for freelance scraps. Then one day, out of the blue, SPIN music editor Craig Marks asked me, “Whatever happened to Bob Stinson?” The result was my first feature for the magazine. Suffice it to say, Bob was in free fall, though his eccentric charm remained, and I tried to write a cautionary tale about an immensely gifted and, frankly, devastated man. Due to my immaturity and fandom, though, the story wasn’t especially nuanced, and it deeply upset his family. Less than two years later, Bob Stinson was dead.

Nothing I’ve ever written has gotten such a visceral reaction. Despite all the garbage-can pollutants that he dumped into his system, Bob was a pure, uncut spirit. At the very least, maybe the story reminded people of why they loved him. The experience also taught me a lesson that took many years to fully understand and absorb. It’s a lesson that many journalists never seem to learn: Some stories don’t need to be told.

Bob, wherever you’re drinkin’, I’m sorry.

3. Kim.

I meddled in the lives of Kim Deal and the Breeders for two long articles in the mid-’90s, and I’m still in awe of her. Her songwriting and personality are uniquely knotty (you get caught up), and she embodied the fun and frustration and absurd self-dramatization of that decade, but also took the piss out of it – mercilessly. She sardonically questioned everyone’s motivations, including her own, but never moaned excuses like so many others. We had a falling out over something I wrote about her sister’s substance abuse — something she insisted I write, but I still should’ve known better. Regardless, I’ll always be grateful — submitting to a sweltering, Cincinnati rock-dive mosh pit, equally split between boys and girls, while pogoing dizzily to “Cannonball,” probably put five years on my life.

4. The Illiterates.

Too many music writers aren’t musicians, or don’t understand how musical equipment works, or don’t read music, so we speak a convoluted Esperanto, generalizing with flowery non sequiturs that hide our illiteracy like a garish scrim. We’re also mostly white and middle class (on average), so when we write about hip-hop and and the African American “ghetto” experience from which it largely springs, our diversionary double-talk revs up. We meet rappers in controlled settings — studios, video shoots, conference rooms — and muse on the authenticity of their presentation. We visit the actual neighborhoods where they grew up (or possibly the more posh areas where they now reside), often with a publicist as a tour guide, and offer some gibes about how their strangely fantastical rhymes bear only a trace relation to either locale.

We can’t speak the language, yet we translate the text.

One of my own favorite illiterate moments came during the week I spent in a Burbank studio with Snoop Dogg, Dr. Dre, and assorted stoned hangers-on while they recorded Snoop’s debut, Doggystyle. One afternoon, Dre finally arose from his producer’s chair and allowed me a few questions. Was there a difference, I probed, between, say, Ice Cube rapping about gangs as an observer and Snoop rapping as an actual ex-gang member. Dre shot me a menacing glare. “Man, I don’t give a fuck about all that,” he spit. “If it’s sellin’, that’s all I care about. If Snoop’s rappin’ about bakin’ a motherfuckin’ cake and it’s gonna sell some records, then I’ll change my name to Dolly Madison in this motherfucker, you know what I’m sayin’?”

Just at that moment, Snoop walked over, turned around, dropped his pants to reveal red polka-dot boxers, and said in a squeaky, mocking voice, “Hey, cuuuzzz.” Dre busted out laughing, then ordered a lackey to mix me a gin and juice.

5. The Vale of Tears

Chris Rock famously joked that Tupac Shakur and the Notorious B.I.G. were not, as some culture vultures opined, “assassinated.” “Them two niggas got shot!” Rock barked with a definitive gleam and cackle.

Thing is, as with so many people from the era of JFK and MLK, I remember exactly where I was when I heard Biggie was killed. I remember going to a bar and drinking pints and crying and laughing about all of hip-hop’s profound lunacy with a friend who had hung out with Big recently. And later, after thinking about how I’d become naively involved with so many artists who were suffering from drug problems and self-destructive behavior, I realized that I had to stop. I had to stop becoming so emotionally obsessed with people whom I really only knew through their music, even though the very appeal of the best music is that it inspires, if not demands, such a passionate immersion. Still, at least as a journalist, if you project yourself into these intense psuedo relationships, you just create a narcissistic clusterfuck that leaves everyone bewildered. In a way, it was a liberating feeling to have that realization, and in a way, it felt deeply empty. In any case, Biggie was dead and I needed to get over myself.

6. In the Middle of the Night in a Dark House Somewhere in the World.

Magazines can have a real impact, but usually not in the way you intend. Polly Jean Harvey was on the 1995 cover of SPIN — deathly pale, exposed and frail, wearing nothing but a girlishly small white bra. Her red lips and dark eyes and thick eyebrows loomed cartoonishly. There was a lot of chatter at the time that she was anorexic and that the cover conveyed a damaging, exploitative image of women. I never formed an opinion, until a couple of years ago. That’s when I interviewed Bradford Cox, of the bands Deerhunter and Atlas Sound, who suffers from Marfan Syndrome, a genetic tissue disorder that can result in a painfully and disproportionately skeletal frame.

“Every birthday from age 11 until 20, my mom got me a subscription to SPIN,” Cox testified. “And I remember getting that cover with PJ Harvey on it. At that time, it was Pavement and the Breeders and PJ Harvey — they were everything to me. And in the photo, she was in her underwear and was so gaunt and almost looked sick, but still strong somehow, and I remember taking that magazine over to my father and showing it to him, and saying, ‘See, Dad, if she can do it, I can do it.’ If somebody who looks like that can be a rock star, then I can look how I look and be accepted.”

Not God’s work, but we do what we can.