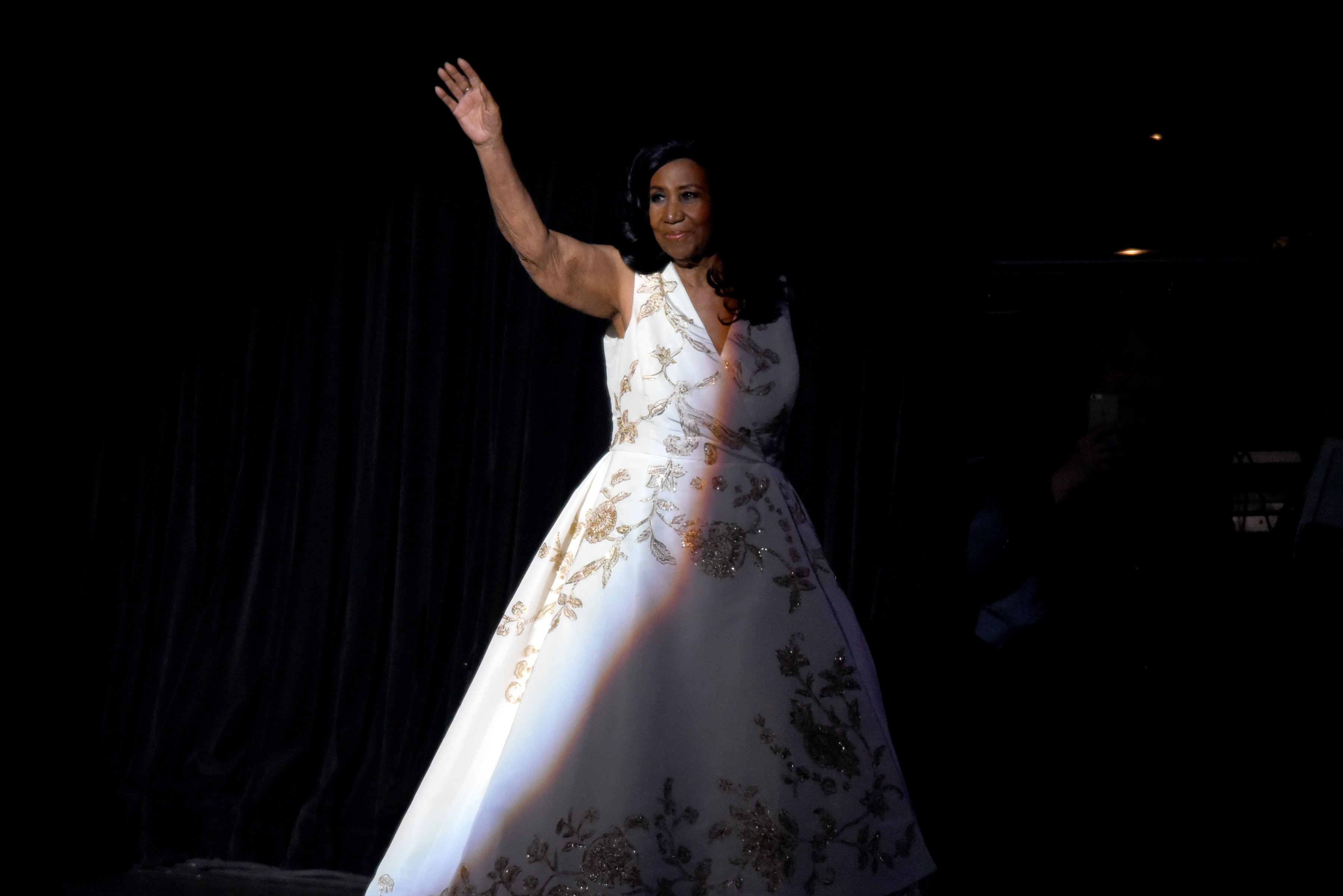

Critic Danyel Smith’s essay on Aretha Franklin, “Dreaming America,” was originally published in the March 1994 issue of Spin. In light of Franklin’s death at age 76, we’re republishing it here.

Aretha Franklin is deep. When neither Mz. Kilo nor Boss nor Yo Yo will do, Aretha will. Willingly or unwillingly, she takes you there. Aretha turns your memory into a moviehouse and pays your way in. Then suddenly, there you are: bigger than life to yourself. With tambourines shaking and organs moaning in time with your life. Pay attention to the background vocals—she hides treasures there, dares you to find them.

Aretha takes you back to ecstatic little times you concentrate so hard on forgetting they end up staying with you forever. The little love times. The fucked-up times. “Day Dreaming and I’m Thinking of You.” The reason, after all, that the bitter is so bitter is that the sweet was mellow and luscious, like a round, red pear. Unbruised and naturally perfect. Aretha takes you into bitter, into torment, takes you there, as I said, without even pausing to ask, without any warning, without any buildup. And so you play her only when you can stand it. You hear her on an accident and you think it’s rude. Somebody should have told you, before they played her. Let you know that Aretha was coming on. “Baby / Will you call me / The moment you get there / Hey baby.”

Soul sister number one. Puffy-faced plain, beautiful Aretha. In a turban. With an Afro all over her head. Permed hair, gigantic wigs. She’s got breasts, a butt, a real-size body. Painted eyebrows. Sporting a Halle Berry bouffant haircut singing “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman” in 1967. Working a look that’s beautiful to people because they believe in your talent. Working that chubby, upper-middle-class shyness. Always looking strange and painted in bright cosmetics. Always looking pained, the hurt on her face showing through the lipstick, eyeliner, and shadow. Always looking like she was yearning for some jeans and sneakers. Or a housecoat and some love.

Also Read

The Best Boxed Sets Of 2023

Aretha Franklin will make you say, with the arrogance of nostalgia, “Ain’t nobody—no Chaka, no Mary J. Blige, no Vesta, no nobody—like Aretha.” “Pitiful / Pitiful / I feel so sorry for me.” Girlfriend had two kids by the time she was 17. She’s singing my blues. Singing yours. She is notorious for her sulkiness, her moods. Girlfriend is screaming my blues. “Love takes care of all my pains and my ills.” Mmmm-hmmm. Whether she wrote it or not, she sang it.

“There is a time for us / I know there is time for us / Time together / A time to learn / A time to care / Somewhere / We’ll find a new way of living / We’ll find a way of forgiving / Somewhere.” But then you remember that Aretha is not dead. She’s alive and well and has a new album coming out. And you think, ain’t no way anything she does now will compare with what she did then. You pull out your Rhino box set, your soundtrack from Sparkle, and you go through each song—”Think,” “Until You Come Back To Me,” “Do Right Woman,” “You’re a Sweet Sweet Man,” “Hooked On Your Love”—all the stuff that puts you on a direct line to there. No longer in control of your own memory, you are suddenly in arms, in conversations, in love. The horrible kind of love that doesn’t exist anymore. You used to picture 1994 and picture the love here, too. But you couldn’t really see Now clearly, Then.

“Givin’ him something he can feel.” Now Aretha’s got you pushed up to the telescope and you can see everything, in all directions, clearly. You remember now the hurt you deny. And then she makes you come back through it alone. “Think / Let your mind go / Let yourself be free.”

When love becomes secondary to everything else, when you don’t have it and you don’t miss it—”It really doesn’t really hurt me that bad”—when you think your heart isn’t broken anymore, when you think you’re as tough as they come, Aretha lets you know that nobody is that lucky, not even you. She rubs the wounds with her big church voice. Sometimes it makes you feel alive, most times it brings the tears you thought were gone. A dreamer herself, she has no problem entering in to anyone else’s. “Hey baby / Let’s get away / Let’s go away far / Baby can we?”